Expanding Services to Detect, Manage, and Prevent Pre-Eclampsia and Eclampsia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Population Distribution in Sindh According to Census 2017 (Population of Karachi: Reality Vs Expectation)

Volume 3, Issue 2, February – 2018 International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology ISSN No:-2456 –2165 Population Distribution in Sindh According to Census 2017 (Population of Karachi: Reality vs Expectation) Dr. Faiza Mazhar TTS Assistant Professor Geography Department. Government College University Faisalabad, Pakistan Abstract—Sindh is our second largest populated province. Historical Populations Growth of Sindh It has a great role in culture and economy of Pakistan. Karachi the largest city of Pakistan in terms of population Census Year Total Population Urban Population also has a unique impact in development of Pakistan. Now 1951 6,047,748 29.23% according to the current census of 2017 Sindh is again 1961 8,367,065 37.85% standing on second position. Karachi is still on top of the list in Pakistan’s ten most populated cities. Population of 1972 14,155,909 40.44% Karachi has not grown on an expected rate. But it was due 1981 19,028,666 43.31% to many reasons like bad law and order situation, miss management of the Karachi and use of contraceptive 1998 29,991,161 48.75% measures. It would be wrong if it is said that the whole 2017 47,886,051 52.02% census were not conducted in a transparent manner. Source: [2] WWW.EN.WIKIPEDIA.ORG. Keywords—Component; Formatting; Style; Styling; Insert Table 1: Temporal Population Growth of Sindh (Key Words) I. INTRODUCTION According to the latest census of 2017 the total number of population in Sindh is 48.9 million. It is the second most populated province of Pakistan. -

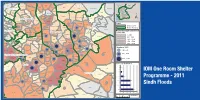

Organizational Presence in Union Councils of Sindh - ER - Floods 2011

Organizational presence in Union Councils of Sindh - ER - Floods 2011 Gilgit Baltistan China ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! !! Khyber Pakhtun! khwa !! ! ! Azad Kashmi!r! Disputed Territory Afghanistan Fata ! 4 Punjab Tangwani Kashmore Thul Balochistan Kashmore India Jacobabad Jacobabad Iran Ubauro Kanhdkot Sindh Shikarpur Garhi Khairo Khanpur (Shikarpur) Ghotki Arabian sea Shahdadkot Shikarpur Qubo Saeed Khan Lakhi Daharki Garhi Yasin Pano Aqil Miro Khan Ghotki Ratodero Sukkur Mirpur Mathelo Kingri Qambar Shahdadkot Rohri Kambar Ali Khan Larkana Khairpur Khangarh Larkana Gambat Warah Bakrani Sukkur Kot Diji Salehpat Dokri Sobodhero Mehar Khairpur Nathan Shah Kandiaro Mirwah Ghulam Shah Bagrani Saeedpur Bhiria Naushahro Feroze Dadu Dadu Naushahro Feroze Faiz Ganj Khairpur Moro Nara Johi Kazi Ahmed Daur Shaheed Benazirabad Nawabshah Sehwan Sinjhoro Barhoon Sakrand Shahdadpur Sanghar Ashgarabad Sinjhoro Sindh Jaffar Khan Laghari Kurkali Jhatia Jhol Khipro Hala Manik ThaheemSyes Sughatullah Shaheed Manjhand Khori Tando Adam Sanghar Hatungo Matiari Jan Nawaz Ali Jamshoro Jhando Mari Matiari Dassori Khahi Mirabad Mirpur Khas Pithoro Thano Bula Khan Kotri Shadi pali Pithoro Saabho Qasimabad Tando Allah Yar Tando Allah Yar Umerkot Hyderabad City Hyderabad Sanjar Chang Dengan Dad Jarwar Samaro Umerkot Hyderabad Kot Ghulam Muhammad Latifabad MMirir pImuamr B uKx Hhadai Bsux Burgury padhario Tando Muhammad Khan Saeed Khan Lund Digri Chachro Matli Sufan Shah Kunri Mulakatyar Mir Khuda Buksh Saeed Matto Lakhat Tando Jan Mohammad Karachi City Thatta Malir -

2015 " 35Th PAKISTAN CONGRESS of ZOOLOGY (INTERNATIONAL) CENTRE OF

PROCEEDINGS OF PAKISTAN CONGRESS OF ZOOLOGY Volume 35, 2015 All the papers in this Proceedings were refereed by experts in respective disciplines THIRTY FOURTH PAKISTAN CONGRESS OF ZOOLOGY held under auspices of THE ZOOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF PAKISTAN at CENTRE OF EXCELLENCE IN MARINE BIOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF KARACHI, KARACHI MARCH 1 – 4, 2015 CONTENTS Acknowledgements i Programme ii Members of the Congress xi Citations Life Time Achievement Award 2015 Late Prof. Dr. Shahzad A. Mufti ............................................xv Dr. Quddusi B. Kazmi .........................................................xvii Dr. Muhammad Ramzan Mirza.............................................xix Abdul Aziz Khan...................................................................xx Zoologist of the year award 2015............................................... xxii Prof. Dr. A.R. Shakoori Gold Medal 2015 ............................... xxiii Prof. Dr. Mirza Azhar Beg Gold Medal 2015 ........................... xxiv Prof. Imtiaz Ahmad Gold Medal 2015 ........................................xxv Prof. Dr. Nasima M. Tirmizi Memorial Gold Medal 2015..........xxvi Gold Medals for M.Sc. and Ph.D. positions 2015 ................... xxviii Certificate of Appreciation .........................................................xxx Research papers SAMI, A.J. JABBAR, B., AHMAD, N., NAZIR, M.T. AND SHAKOORI, A.R. in silico analysis of structure-function relationship of a neutral lipase from Tribolium castaneum .......................... 1 KHAN, I., HUSSAIN, A., KHAN, A. AND -

Essays on the History of Sindh.Pdf

Essays On The History of Sindh Mubarak Ali Reproduced by Sani H. Panhwar (2019) CONTENTS Introduction .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 1 Historiography of Sindh .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 6 Nasir Al-Din Qubachah (1206-1228) .. .. .. .. .. .. 12 Lahribandar: A Historical Port of Sindh .. .. .. .. .. 22 The Portuguese in Sindh .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 29 Sayyid Ahmad Shahid In Sindh .. .. .. .. .. .. 35 Umarkot: A Historic City of Sindh .. .. .. .. .. .. 39 APPENDIX .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 49 Relations of Sindh with Central Asia .. .. .. .. .. .. 70 Reinterpretation of Arab Conquest of Sindh .. .. .. .. .. 79 Looters are 'great men' in History! .. .. .. .. .. .. 81 Index .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 85 INTRODUCTION The new history creates an image of the vanquished from its own angle and the defeated nation does not provide any opportunity to defend or to correct historical narrative that is not in its favour. As a result, the construction of the history made by the conquerors becomes valid without challenge. A change comes when nations fight wars of liberation and become independent after a long and arduous struggle. During this process, leaders of liberation movements are required to use history in order to fulfil their political ends. Therefore, attempts are made to glorify the past to counter the causes of their subjugation. A comprehensive plan is made to retrieve their lost past and reconstruct history to rediscover their traditions and values and strengthen their national identity. However, in some cases, subject nations are so much integrated to the culture of their conquerors that they lose their national identity and align themselves with foreign culture. They accept their version of history and recognize the aggressors as their heroes who had liberated them from their inefficient rulers and, after elimination of their out- dated traditions, introduced them to modern values and new ideas. -

Building Back Stronger

IOM One Room Shelters - 2011 Sindh Floods Response uc, manjhand odero lal village kamil hingoro jhando mari Punjab sekhat khirah Balochistan dasori San gha r ismail jo goth odero lal station khan khahi bilawal hingorjo Matiari roonjho khokhrapar matiari mirabad balouchabad tando soomro chhore bau khan pathan piyaro lund turk ali mari mirpurkhas-05 Sindh shaikh moosa daulatpur shadi pali tajpur pithoro shah mardan shah dhoro naro i m a khan samoon sabho kaplore jheluri Tando Allahpak singhar Yar mosu khatian ii iii iv missan tandojam dhingano bozdar hingorno khararo syed umerkot mirpur old haji sawan khan satriyoon Legend atta muhammad palli tando qaiser araro bhurgari began jarwar mir ghulam hussain Union Council bukera sharif tando hyder dengan sanjar chang mirwah Ume rkot District Boundary hoosri gharibabad samaro road dad khan jarwar girhore sharif seriHyd erabmoolan ad Houses Damaged & Destroyed tando fazal chambar-1 chambar-2 Mirpur Khas samaro kangoro khejrari - Flood 2011 mir imam bux talpur latifabad-20 haji hadi bux 1 - 500 kot ghulam muhammad bhurgari mir wali muhammad latifabad-22 shaikh bhirkio halepota faqir abdullah seri 501 - 1500 ghulam shah laghari padhrio unknown9 bustan manik laghari digri 1501 - 2500 khuda dad kunri 2501 - 3500 uc-iii town t.m. khan pabban tando saindad jawariasor saeedpur uc-i town t.m. khan malhan 3501 - 5000 tando ghulam alidumbalo shajro kantio uc-ii town t.m. khan phalkara kunri memon Number of ORS dilawar hussain mir khuda bux aahori sher khan chandio matli-1 thari soofan shah nabisar road saeed -

Ehsaas Emergency Cash Payments

Consolidated List of Campsites and Bank Branches for Ehsaas Emergency Cash Payments Campsites Ehsaas Emergency Cash List of campsites for biometrically enabled payments in all 4 provinces including GB, AJK and Islamabad AZAD JAMMU & KASHMIR SR# District Name Tehsil Campsite 1 Bagh Bagh Boys High School Bagh 2 Bagh Bagh Boys High School Bagh 3 Bagh Bagh Boys inter college Rera Dhulli Bagh 4 Bagh Harighal BISP Tehsil Office Harigal 5 Bagh Dhirkot Boys Degree College Dhirkot 6 Bagh Dhirkot Boys Degree College Dhirkot 7 Hattain Hattian Girls Degree Collage Hattain 8 Hattain Hattian Boys High School Chakothi 9 Hattain Chakar Boys Middle School Chakar 10 Hattain Leepa Girls Degree Collage Leepa (Nakot) 11 Haveli Kahuta Boys Degree Collage Kahutta 12 Haveli Kahuta Boys Degree Collage Kahutta 13 Haveli Khurshidabad Boys Inter Collage Khurshidabad 14 Kotli Kotli Govt. Boys Post Graduate College Kotli 15 Kotli Kotli Inter Science College Gulhar 16 Kotli Kotli Govt. Girls High School No. 02 Kotli 17 Kotli Kotli Boys Pilot High School Kotli 18 Kotli Kotli Govt. Boys Middle School Tatta Pani 19 Kotli Sehnsa Govt. Girls High School Sehnsa 20 Kotli Sehnsa Govt. Boys High School Sehnsa 21 Kotli Fatehpur Thakyala Govt. Boys Degree College Fatehpur Thakyala 22 Kotli Fatehpur Thakyala Local Govt. Office 23 Kotli Charhoi Govt. Boys High School Charhoi 24 Kotli Charhoi Govt. Boys Middle School Gulpur 25 Kotli Charhoi Govt. Boys Higher Secondary School Rajdhani 26 Kotli Charhoi Govt. Boys High School Naar 27 Kotli Khuiratta Govt. Boys High School Khuiratta 28 Kotli Khuiratta Govt. Girls High School Khuiratta 29 Bhimber Bhimber Govt. -

Sweet Anecdotes of Four Beloved Imams

“This is an end of the age, and those who are faithful will behold power and miracle of their Imam of the Age, but those having imperfect hearts will however behold miracle publicly, but falsify them. Those who don’t trust in the powers and supernatural events of the Prophet, Apostle and the Imam; their resemblance is that of the stone-blind person. If the mirror and a piece of an earthen vessel are given to the stone-blind person - both of them are alike for him.” - Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah, Bombay, 1st September, 1885 201 - Sweet Anecdotes of Four Beloved Imams By: Mumtaz Ali Tajddin S.Ali [email protected] 1. Imam Hasan Ali Shah : 16 2. Imam Aga Ali Shah : 21 3. Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah : 152 4 Mawlana Hazar Imam : 36 Total : 225 This write-up is dedicated in loving memory of late Vazir Ghulam Hussain Mohammad Ali Dharas (1903-1973) Sponsor by Kamadia Salim Dharas, Albuqurque, USA. It will be a part and parcel of my life to remember the outstanding co-operation of Kamadia Salim Dharas, who indeed remained a driving force of my study during last 15 years. I owe a special debt of gratitude to him for his humble sponsorship, assistance and encouragement. (Rai Mumtaz Ali Tajddin S. Ali) 1 Imam Hasan Ali Shah (1)In 1838, Rai Ramumal came in Karachi from Punjab with a box of the karsazi (religious dues). He was also accompanied by some ladies for the didar of Imam Hasan Ali Shah in Mahallat, Iran. They had to go Port Abbas from Karachi by sea, thence they were to proceed to Kirman by highways. -

2020-05-12 --Locust Report.Cdr

Locust Situation Report May 2020 LOCUST INFESTATION BACKGROUND ASSESSMENT OF OBJECTIVES: The main objecve of the rapid needs assessment is to inform humanitarian organizaon, aid agencies and donors on current status of the locust infestaon in TRDP Programme are; the impact of the infestaon on people's food security and livelihoods - i.e. arable land, herbs, shrubs and trees; urgent needs to tackle infestaon and to address consequent humanitarian needs. The 2019-20 locust swarm in Pakistan is an districts of Sindh aer inially aacking outbreak of desert locusts, which is Khirpur, sparking fears of large-scale crop TARGETED DISTRICTS: threatening the food supply across the country. devastaon in barrage areas. According to Tharparkar, Umerkot, Dadu, Jamshoro & Tando Since June 2019, the locust outbreak has been media reports, locusts aacked on agricultural Allahyar affecng eastern Pakistan. In November 2019, fields and tress in Dadu, Maari, Jamshoro, Karachi saw the first locust aack in the city Nawabashah, Naushehro Feroze and Sanghar, METHODOLOGY: aer 1961. On 1 February 2020, the Pakistani Umerkot, Tharparkar, Khirpur and Hyderabad The Rapid Needs Assessment has been carried Government declared a naonal emergency to districts. "Locusts can destroy the agricultural out by TRDP, with quesonnaire. Interviews protect crops and help farmers. The current belt of Sindh if they entered Mirpurkhas, Tando took place on May 2020. desert locust situaon remains extreme Allahyar, Maari, Hyderabad and other alarming Swarms of locusts have spread to six districts on the le bank of Indus River. Locust Situaon Report May 2020 DISTRICT WISE LOCUST SITUATION LOCUST SITUATION: THARPARKAR Mosepota, Roheera, Kuo, Verhari Drs, Mithrio The Desert Locust, found in various parts of Tharparkar, considered the most destrucve Union Councils migratory pest because they are highly mobile and can form swarms containing millions of 70 64 locusts, leading to devastang impacts on 60 crops, trees, pasture and fodder. -

List of Dehs in Sindh

List of Dehs in Sindh S.No District Taluka Deh's 1 Badin Badin 1 Abri 2 Badin Badin 2 Achh 3 Badin Badin 3 Achhro 4 Badin Badin 4 Akro 5 Badin Badin 5 Aminariro 6 Badin Badin 6 Andhalo 7 Badin Badin 7 Angri 8 Badin Badin 8 Babralo-under sea 9 Badin Badin 9 Badin 10 Badin Badin 10 Baghar 11 Badin Badin 11 Bagreji 12 Badin Badin 12 Bakho Khudi 13 Badin Badin 13 Bandho 14 Badin Badin 14 Bano 15 Badin Badin 15 Behdmi 16 Badin Badin 16 Bhambhki 17 Badin Badin 17 Bhaneri 18 Badin Badin 18 Bidhadi 19 Badin Badin 19 Bijoriro 20 Badin Badin 20 Bokhi 21 Badin Badin 21 Booharki 22 Badin Badin 22 Borandi 23 Badin Badin 23 Buxa 24 Badin Badin 24 Chandhadi 25 Badin Badin 25 Chanesri 26 Badin Badin 26 Charo 27 Badin Badin 27 Cheerandi 28 Badin Badin 28 Chhel 29 Badin Badin 29 Chobandi 30 Badin Badin 30 Chorhadi 31 Badin Badin 31 Chorhalo 32 Badin Badin 32 Daleji 33 Badin Badin 33 Dandhi 34 Badin Badin 34 Daphri 35 Badin Badin 35 Dasti 36 Badin Badin 36 Dhandh 37 Badin Badin 37 Dharan 38 Badin Badin 38 Dheenghar 39 Badin Badin 39 Doonghadi 40 Badin Badin 40 Gabarlo 41 Badin Badin 41 Gad 42 Badin Badin 42 Gagro 43 Badin Badin 43 Ghurbi Page 1 of 142 List of Dehs in Sindh S.No District Taluka Deh's 44 Badin Badin 44 Githo 45 Badin Badin 45 Gujjo 46 Badin Badin 46 Gurho 47 Badin Badin 47 Jakhralo 48 Badin Badin 48 Jakhri 49 Badin Badin 49 janath 50 Badin Badin 50 Janjhli 51 Badin Badin 51 Janki 52 Badin Badin 52 Jhagri 53 Badin Badin 53 Jhalar 54 Badin Badin 54 Jhol khasi 55 Badin Badin 55 Jhurkandi 56 Badin Badin 56 Kadhan 57 Badin Badin 57 Kadi kazia -

MCHIP Pakistan End-Of-Project Report PAKISTAN ASSOCIATE AWARD/COMPONENT 2 MATERNAL NEWBORN and CHILD HEALTH SERVICES

MCHIP Pakistan End-of-Project Report PAKISTAN ASSOCIATE AWARD/COMPONENT 2 MATERNAL NEWBORN AND CHILD HEALTH SERVICES Authors: Presha Regmi Farhana Shahid Kamran Baig Emma Williams Reporting period: February 2013–March 2018 Submitted on: Submitted to: United States Agency for International Development / Pakistan under Cooperative Agreement # 656- A-00-11-00097-00 The Maternal and Child Health Integrated Program (MCHIP) is the USAID Bureau for Global Health’s flagship maternal, neonatal, and child health (MNCH) program. MCHIP supports programming in maternal, newborn, and child health, immunization, family planning, malaria, nutrition, and HIV/AIDS, and strongly encourages opportunities for integration. Cross-cutting technical areas include water, sanitation, hygiene, urban health and health systems strengthening. This report was made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), under the terms of the Leader with Associates Cooperative Agreement GHS-A-00-08-00002-00. The contents are the responsibility of the Maternal and Child Health Integrated Program (MCHIP) and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. October 2018 Table of Contents List of Figures and Tables ........................................................................................................... iv Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................... v Executive -

104 Faculty Wise Distribution of Merit Seats for Various Districts of Sindh

Faculty Wise Distribution of Merit Seats for Various Districts of Sindh. R = Rural U= Urban B.Sc (Agri.) Hons. B.E (Agri) DVM BSIT B.Sc (Hons) Faculty of Faculty of Faculty of Faculty of Faculty of Animal Information Institute of Food Division / District Agricultural Crop Crop Social Agricultural Husbandry & Technology Science & Production Protection Sciences Engineering Veterinary Sciences Centre Technology Total HYDERABAD DIVISION R U R U R U R U R U R U R U Hyderabad 20 5 10 3 8 2 7 2 7 2 11 3 2 1 83 Tando Allahyar 6 2 4 1 2 1 2 1 2 1 3 1 1 0 27 Tando Muhammad Khan 6 1 4 1 3 1 2 1 2 1 3 1 1 0 27 Matiari 7 2 4 1 3 1 2 1 2 1 3 1 1 0 29 Badin 13 3 8 2 6 1 5 1 5 1 7 2 2 1 57 Thatta 7 2 4 1 4 1 3 1 3 1 6 1 1 0 35 Sujawal 6 1 4 1 2 1 2 0 2 0 3 1 2 0 25 Dadu 14 3 9 2 5 1 5 1 5 1 8 2 2 0 58 Jamshoro 7 2 4 1 3 1 3 1 3 1 5 1 2 1 35 Sub-Total 86 21 51 13 36 10 31 9 31 9 49 13 14 3 376 MIRPURKHAS DIVISION Mirpurkhas 12 3 7 2 5 1 4 1 4 1 8 2 2 1 53 Umerkot 8 2 4 1 3 1 3 1 3 1 6 1 2 0 36 Tharparkar 11 3 6 1 5 1 4 1 4 1 7 2 2 1 49 Sub-Total 31 8 17 4 13 3 11 3 11 3 21 5 6 2 138 SHAHEED BENAZIRABAD DIVISION Shaheed Benazir Abad 14 3 7 2 6 1 5 1 5 1 7 2 2 0 55 Noushehro Feroze 13 3 8 2 5 1 5 1 5 1 8 2 2 0 55 Sanghar 16 4 9 2 6 1 6 1 6 1 9 2 3 1 69 Sub-Total 43 10 24 6 17 3 16 3 16 3 24 6 7 1 179 SUKKUR DIVISION Sukkur 12 3 6 1 5 1 4 1 4 1 6 2 2 0 48 Ghotki 13 3 7 2 4 1 4 1 4 1 6 2 2 0 50 Khairpur 20 5 10 3 8 2 7 2 7 2 10 3 2 1 82 Sub-Total 45 11 23 6 17 4 15 4 15 4 22 7 6 1 180 LARKANA DIVISION Larkana 12 3 6 2 4 1 4 1 4 1 8 2 2 1 51 Qambar / Shahdad Kot 11 3 6 1 5 1 4 1 4 1 7 2 2 0 48 Shikarpur 11 3 6 1 5 1 4 1 4 1 6 2 2 1 48 Jacobabad 9 2 5 1 3 1 3 1 3 1 5 1 2 0 37 Kashmore 9 2 4 1 4 1 3 1 3 1 5 1 1 0 36 Sub-Total 52 13 27 6 21 5 18 5 18 5 31 8 9 2 220 Karachi Division 6 2 2 1 2 1 2 1 2 1 2 1 2 0 25 Grand Total 263 65 144 36 106 26 93 25 93 25 149 40 44 9 1118 104 FACULTY WISE BREAKUP OF SEATS FOR VARIOUS CATEGORIES B.Sc (Hons) B.Sc (Agri.) Hons. -

Qatari Stocks Set to Lure $5 Bn in Foreign Funds

WEDNESDAY DECEMBER 5, 2018 RABI AL-AWWAL 27, 1440 VOL.12 NO. 4474 QR 2 FINE Fajr: 4:42 am Dhuhr: 11:25 am HIGH : 26°C Asr: 2:24 pm Maghrib: 4:44 pm LOW : 20°C Isha: 6:14 pm Business 12 Sports 16 Eventful fourth quarter for Qatar Kipchoge, Ibarguen are Central Securities Depository 2018 Athletes of the Year 2019 BOOK FAIR OCCUPIES A CENTRAL POSITION ‘Amir’s visit to Malaysia ON QATARI CULTURAL SCENE: AMIR will boost bilateral ties’ THE Amir HH Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al Thani has af- QNA includes the distribution of the firmed that the Doha Inter- KUALA LUMPUR awards of the third edition of the national Book Fair occupies Sheikh Tamim Bin Hamad Al Tha- a central position on the THE visit of the Amir HH Sheikh ni International Anti-Corruption Qatari cultural scene. Tamim bin Hamad al Thani to Ma- Excellence Award. Malaysia has “Today I was delighted laysia is of great importance in the been selected as a place to distrib- to visit the Doha Interna- light of Qatar’s policy to expand its ute the awards in recognition of tional Book Fair, which is relations with friendly countries the efforts of the Malaysian gov- central to the Qatari cultural in political, economic and cultural ernment that launched an exten- scene,” the Amir said in a spheres, Qatar’s Ambassador to sive anti-corruption campaign in tweet. “We build more indi- Malaysia HE Fahad bin Moham- the country since it took office, the vidual and collective aware- med Kafood has said.