Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Nineteenth-Century American Theatre: the Image

Burlesquing “Otherness” 101 Burlesquing “Otherness” in Nineteenth-Century American Theatre: The Image of the Indian in John Brougham’s Met-a-mora; or, The Last of the Pollywogs (1847) and Po-Ca-Hon-Tas; or, The Gentle Savage (1855). Zoe Detsi-Diamanti When John Brougham’s Indian burlesque, Met-a-mora; or, The Last of the Pollywogs, opened in Boston at Brougham’s Adelphi Theatre on November 29, 1847, it won the lasting reputation of an exceptional satiric force in the American theatre for its author, while, at the same time, signaled the end of the serious Indian dramas that were so popular during the 1820s and 1830s. Eight years later, in 1855, Brougham made a most spectacular comeback with another Indian burlesque, Po-Ca-Hon-Tas; or, The Gentle Savage, an “Original, Aboriginal, Erratic, Operatic, Semi-Civilized, and Demi-savage Extravaganza,” which was produced at Wallack’s Lyceum Theatre in New York City.1 Both plays have been invariably cited as successful parodies of Augustus Stone’s Metamora; or, The Last of the Wampanoags (1829) and the stilted acting style of Edwin Forrest, and the Pocahontas plays of the first half of the nineteenth century. They are sig- nificant because they opened up new possibilities for the development of satiric comedy in America2 and substantially contributed to the transformation of the stage picture of the Indian from the romantic pattern of Arcadian innocence to a view far more satirical, even ridiculous. 0026-3079/2007/4803-101$2.50/0 American Studies, 48:3 (Fall 2007): 101-123 101 102 Zoe Detsi-Diamanti -

Il Lasca’ (1505‐1584) and the Burlesque

Antonfrancesco Grazzini ‘Il Lasca’ (1505‐1584) and the Burlesque Poetry, Performance and Academic Practice in Sixteenth‐Century Florence Antonfrancesco Grazzini ‘Il Lasca’ (1505‐1584) en het burleske genre Poëzie, opvoeringen en de academische praktijk in zestiende‐eeuws Florence (met een samenvatting in het Nederlands) Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit Utrecht op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof.dr. J.C. Stoof, ingevolge het besluit van het college voor promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op dinsdag 9 juni 2009 des ochtends te 10.30 uur door Inge Marjo Werner geboren op 24 oktober 1973 te Utrecht Promotoren: Prof.dr. H.A. Hendrix Prof.dr. H.Th. van Veen Contents List of Abbreviations..........................................................................................................3 Introduction.........................................................................................................................5 Part 1: Academic Practice and Poetry Chapter 1: Practice and Performance. Lasca’s Umidian Poetics (1540‐1541) ................................25 Interlude: Florence’s Informal Literary Circles of the 1540s...........................................................65 Chapter 2: Cantando al paragone. Alfonso de’ Pazzi and Academic Debate (1541‐1547) ..............79 Part 2: Social Poetry Chapter 3: La Guerra de’ Mostri. Reviving the Spirit of the Umidi (1547).......................................119 Chapter 4: Towards Academic Reintegration. Pastoral Friendships in the Villa -

The Rise and Fall of Fair Use: the Protection of Literary Materials Against Copyright Infringement by New and Developing Media

South Carolina Law Review Volume 20 Issue 2 Article 1 1968 The Rise and Fall of Fair Use: The Protection of Literary Materials Against Copyright Infringement by New and Developing Media Hugh J. Crossland Boston University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/sclr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Hugh J. Crossland, The Rise and Fall of Fair Use: The Protection of Literary Materials Against Copyright Infringement by New and Developing Media, 20 S. C. L. Rev. 153 (1968). This Article is brought to you by the Law Reviews and Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in South Carolina Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Crossland:THE RISE The Rise AND and FallFALL of Fair Use:OF The FAIR Protection USE: of Literary Materia THE PROTECTION OF LITERARY MATERIALS AGAINST COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENT BY NEW AND DEVELOPING MEDIA HuGH J. CROSSLAND* St. Coumba, sitting up all night to do it, furtively made a copy of abbot Fennian's Psalter, and how the abbot protested as loudly as if he had been a member of the Stationers Company, and brought an action in detinue, or its Irsh equivalent, for Columba's copy, and how King Diarmid sitting in Tara's halls, not then deserted, gave judgment for the abbot .... I. INTRODUCTION Many copies of literary material-books and periodicals- have been made in violation of the law. The growing use' of copying machines is causing a decline in the market for litera- ture, is unfair competition2 to the publisher and copyright owner, and has possible constitutional significance.3 Although the copyright statute4 grants absolute rights5 protecting writ- ings that are published in accordance with its provisions, the courts have put a gloss on the statute by allowing non-infringing * Assistant Professor of Law, Boston University School of Law; B.B.A., M.B.A., University of Michigan; J.D., Wayne State University; LL.M., Yale University; Member of the Michigan Bar. -

Tolono Library CD List

Tolono Library CD List CD# Title of CD Artist Category 1 MUCH AFRAID JARS OF CLAY CG CHRISTIAN/GOSPEL 2 FRESH HORSES GARTH BROOOKS CO COUNTRY 3 MI REFLEJO CHRISTINA AGUILERA PO POP 4 CONGRATULATIONS I'M SORRY GIN BLOSSOMS RO ROCK 5 PRIMARY COLORS SOUNDTRACK SO SOUNDTRACK 6 CHILDREN'S FAVORITES 3 DISNEY RECORDS CH CHILDREN 7 AUTOMATIC FOR THE PEOPLE R.E.M. AL ALTERNATIVE 8 LIVE AT THE ACROPOLIS YANNI IN INSTRUMENTAL 9 ROOTS AND WINGS JAMES BONAMY CO 10 NOTORIOUS CONFEDERATE RAILROAD CO 11 IV DIAMOND RIO CO 12 ALONE IN HIS PRESENCE CECE WINANS CG 13 BROWN SUGAR D'ANGELO RA RAP 14 WILD ANGELS MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 15 CMT PRESENTS MOST WANTED VOLUME 1 VARIOUS CO 16 LOUIS ARMSTRONG LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB JAZZ/BIG BAND 17 LOUIS ARMSTRONG & HIS HOT 5 & HOT 7 LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB 18 MARTINA MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 19 FREE AT LAST DC TALK CG 20 PLACIDO DOMINGO PLACIDO DOMINGO CL CLASSICAL 21 1979 SMASHING PUMPKINS RO ROCK 22 STEADY ON POINT OF GRACE CG 23 NEON BALLROOM SILVERCHAIR RO 24 LOVE LESSONS TRACY BYRD CO 26 YOU GOTTA LOVE THAT NEAL MCCOY CO 27 SHELTER GARY CHAPMAN CG 28 HAVE YOU FORGOTTEN WORLEY, DARRYL CO 29 A THOUSAND MEMORIES RHETT AKINS CO 30 HUNTER JENNIFER WARNES PO 31 UPFRONT DAVID SANBORN IN 32 TWO ROOMS ELTON JOHN & BERNIE TAUPIN RO 33 SEAL SEAL PO 34 FULL MOON FEVER TOM PETTY RO 35 JARS OF CLAY JARS OF CLAY CG 36 FAIRWEATHER JOHNSON HOOTIE AND THE BLOWFISH RO 37 A DAY IN THE LIFE ERIC BENET PO 38 IN THE MOOD FOR X-MAS MULTIPLE MUSICIANS HO HOLIDAY 39 GRUMPIER OLD MEN SOUNDTRACK SO 40 TO THE FAITHFUL DEPARTED CRANBERRIES PO 41 OLIVER AND COMPANY SOUNDTRACK SO 42 DOWN ON THE UPSIDE SOUND GARDEN RO 43 SONGS FOR THE ARISTOCATS DISNEY RECORDS CH 44 WHATCHA LOOKIN 4 KIRK FRANKLIN & THE FAMILY CG 45 PURE ATTRACTION KATHY TROCCOLI CG 46 Tolono Library CD List 47 BOBBY BOBBY BROWN RO 48 UNFORGETTABLE NATALIE COLE PO 49 HOMEBASE D.J. -

Rose La Rose and the Re-Ownership of American Burlesque, 1935-1972

TAUGHT IT TO THE TRADE: ROSE LA ROSE AND THE RE-OWNERSHIP OF AMERICAN BURLESQUE, 1935-1972 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Elizabeth Wellman Graduate Program in Theatre The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Jennifer Schlueter, Advisor Beth Kattelman Joy Reilly Copyright by Elizabeth Wellman 2015 ABSTRACT Declaring burlesque dead has been a habit of the twentieth century. Robert C. Allen quoted an 1890s letter from the first burlesque star of the American stage, Lydia Thompson in Horrible Prettiness: Burlesque and American Culture (1991): “[B]urlesque as she knew it ‘has been retired for a time,’ its glories now ‘merely memories of the stage.’”1 In 1931, Bernard Sobel opined in Burleycue: An Underground History of Burlesque Days, “Alas! You will never get a chance to see one of the real burlesque shows again. They are gone forever…”2 In 1938, The Billboard published an editorial that began, “On every hand the cry is ‘Burlesque is dead.’”3 In fact, burlesque had been declared dead so often that editorials began popping up insisting it could be revived, as Joe Schoenfeld’s 1943 op-ed in Variety did: “[It] may be in a state of putrefaction, but it is a lusty and kicking decomposition.”4 It is this “lusty and kicking decomposition” which characterizes the published history of burlesque. Since its modern inception in the late nineteenth century, American burlesque has both been framed and framed itself within this narrative of degeneration. -

Thesis-1969-P769l.Pdf

THE IMPORTANCE OF THE BURLESQUE ASPECTS OF JOSEPH.ANDREWS, A NOVEL BY HENRY FIELDING By ANNA COLLEEN POLK Bachelor of Arts Northeastern State College Tahlequah, Oklahoma 1964 Submitted to the Faculty ot the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 1969 __ j OKLAHOMA STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 8iP 291969 THE IMPORTANCE OF THE BURLESQUE ASPECTS OF JOSEPH ANDREWS, A NOVEL BY HENRY FIELDING Thesis Approved: ~~ £~ 1{,· if'~ Jr-- Dean of the Graduate College 725038 ii PREFACE This thesis explores the·impottance of the burlesque aspects of Joseph Andrews, a novel by Henry Fielding· published in 1742. The· Preface. of.· the novel set forth a comic. theory which was entirely English and-which Fielding describes as a·11kind of writing, which l do not remember-· to have seen· hitherto attempted in our language". (xvii) •1 . The purpose of this paper will be to d.iscuss. the influence o:f; the burlesque .in formulating the new-genre which Fielding implies is the cow,:l..c equivalent of the epic. Now, .·a· comic· romance is a comic epic poem in prose 4iffering from comedy, as the--·serious epic from tragedy its action· being· more extended ·and· c'omp:rehensive; con tainiµg ·a ·much larger circle of·incidents, and intro ducing a greater ·variety of characters~ - lt differs :f;rO'J;l;l the serious romance in its fable and action,. in· this; that as in the one·these are·grave and solemn, ~o iil the other they·are·light:and:ridiculous: it• differs in its characters by introducing persons of. -

Believe: the Music of Cher Seattle Men's Chorus Encore Arts Seattle

MARCH 2019 the music of MARCH 30 & 31 | ARTISTIC DIRECTOR PAUL CALDWELL | SEATTLECHORUSES.ORG With the nation’s premier Cher impersonator and winner of RuPaul’s Drag Race All Stars, CHAD MICHAELS BYLANDBYSEA BYEXPERTS With unmatched experience and insider knowledge, we are the Alaska experts. No other cruise line gives you more options to see Glacier Bay. Plus, only we give you the premier Denali National Park adventure at our own McKinley Chalet Resort combined with access to the majestic Yukon Territory. It’s clear, there’s no better way to see Alaska than with Holland America Line. Call your Travel Advisor or 1-877-SAIL HAL, or visit hollandamerica.com Ships’ Registry: The Netherlands HAL 14038-4 Alaska4up_SeattleChorus_V1.indd 1 2/12/19 5:04 PM Pub/s: Seattle Chorus Traffic: 2/12/19 Run Date: March Color: CMYK Author: SN Trim: 8.375"wx10.875"h Live: 7.375"w x 9.875"h Bleed: 8.625"w x 11.125"h Version#: 1 FROM THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR I’ve said it before: refrains of hate and division that fall Seattle takes queens on the ears of his students every day. very seriously. If This was an invitation to do something RuPaul is on TV, different, something bold, something you can’t get a really beautiful. seat at any of So every winter, I go to the school the Capitol Hill weekly. But I don’t go alone. Singers establishments. from Seattle Men’s and Women’s Everything is jam-packed. And the Choruses take off work to be there exuberance of the fans rivals that of with me at 8:55 every Thursday the 12th man at a Seahawks game. -

When Authors Won't Sell: Parody, Fair Use, and Efficiency in Copyright Law Alfred C

Boston College Law School Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School Boston College Law School Faculty Papers January 1991 When Authors Won't Sell: Parody, Fair Use, and Efficiency in Copyright Law Alfred C. Yen Boston College Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/lsfp Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Alfred C. Yen. "When Authors Won't Sell: Parody, Fair Use, and Efficiency in Copyright Law." University of Colorado Law Review 62, (1991): 79-108. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law School Faculty Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHEN AUTHORS WON'T SELL: PARODY, FAIR USE, AND EFFICIENCY IN COPYRIGHT LAW ALFRED C. YEN· I. INTRODUCTION This article considers whether the fair use treatment of parodyl in copyright law2 is economically efficient. 3 The inquiry is undertaken • B.S., M.S., Stanford University; 1.0. Harvard Law School. Assistant Professor of Law, Boston College Law School. The author would like to thank Frank Upham, Ralph Brown, Wendy Gordon and Dave Sunding for their comments. Thanks are also owed to Tracy Tanaka and Kelly Cournoyer for their able research assistance. This article was made possible by the author's receipt of a Dr. Thomas Carney Law Faculty Research Grant from Boston College Law School and a Faculty Research Expense Grant from Boston College. -

Sing Solo Pirate: Songs in the Key of Arrr! a Literature Guide for the Singer and Vocal Pedagogue

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music Music, School of 5-2013 Sing Solo Pirate: Songs in the Key of Arrr! A Literature Guide for the Singer and Vocal Pedagogue Michael S. Tully University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent Part of the Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, and the Music Practice Commons Tully, Michael S., "Sing Solo Pirate: Songs in the Key of Arrr! A Literature Guide for the Singer and Vocal Pedagogue" (2013). Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music. 62. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent/62 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. SING SOLO PIRATE: SONGS IN THE KEY OF ARRR! A LITERATURE GUIDE FOR THE SINGER AND VOCAL PEDAGOGUE by Michael S. Tully A DOCTORAL DOCUMENT Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Major: Music Under the Supervision of Professor William Shomos Lincoln, Nebraska May, 2013 SING SOLO PIRATE: SONGS IN THE KEY OF ARRR! A LITERATURE GUIDE FOR THE SINGER AND VOCAL PEDAGOGUE Michael S. Tully, D.M.A. University of Nebraska, 2013 Advisor: William Shomos Pirates have always been mysterious figures. -

San Diego's Bygone Burlesque: the Famous

San Diego’s Bygone Burlesque: The Famous Hollywood Theatre1 Winner of the Joseph L. Howard Memorial Award by Jaye Furlonger Burlesque, one of America’s most significant contributions to popular entertainment in the pre-radio and television era, played an important role in San Diego’s social and cultural history. The legendary Hollywood Theatre put the city on the map as one of the best places in the entire country to find “big time” burlesque, often referred to as the “poor man’s musical comedy.”2 During the 1940s and 1950s, it became a major stopping point on the West Coast circuit for such big-name striptease artists as Tempest Storm, Betty Rowland, and Lili St. Cyr.3 The 1960s, however, brought an end to its “golden era,” and by 1970 the Hollywood was the last great burlesque palace to close on the West Coast. The construction of Horton Plaza in the 1980s eliminated any visible trace of the colorful, bygone world that existed at 314-316 F Street. People now park their cars where the Hollywood once stood and look to shopping and movies for entertainment, not musical comedy. The glamorous headlining striptease artists seductively advertised on the marquee and the droves of young sailors who crowded the sidewalk lining up to see pretty girls and comics have faded into the past. Early burlesque takes root in San Diego: 1880s – 1920s The first American burlesque shows developed in eastern metropolitan centers during the late nineteenth century. The shows played on people’s desires to laugh and lust, the key factors that helped spread its popularity to the far reaches of the country, despite its perceived threat to the social and moral order. -

“Flowers in the Desert”: Cirque Du Soleil in Las Vegas, 1993

“FLOWERS IN THE DESERT”: CIRQUE DU SOLEIL IN LAS VEGAS, 1993-2012 by ANNE MARGARET TOEWE B.S., The College of William and Mary, 1987 M.F.A., Tulane University, 1991 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Theatre & Dance 2013 This thesis entitled: “Flowers in the Desert”: Cirque du Soleil in Las Vegas 1993 – 2012 written by Anne Margaret Toewe has been approved for the Department of Theatre & Dance ______________________________________________ Dr. Oliver Gerland (Committee Chair) ______________________________________________ Dr. Bud Coleman (Committee Member) Date_______________________________ The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. iii Toewe, Anne Margaret (Ph.D., Department of Theatre & Dance) “Flowers in the Desert”: Cirque du Soleil in Las Vegas 1993 – 2012 Dissertation directed by Professor Oliver Gerland This dissertation examines Cirque du Soleil from its inception as a small band of street performers to the global entertainment machine it is today. The study focuses most closely on the years 1993 – 2012 and the shows that Cirque has produced in Las Vegas. Driven by Las Vegas’s culture of spectacle, Cirque uses elaborate stage technology to support the wordless acrobatics for which it is renowned. By so doing, the company has raised the bar for spectacular entertainment in Las Vegas I explore the beginning of Cirque du Soleil in Québec and the development of its world-tours. -

Lvb-0618-Bhof

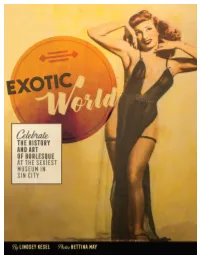

Pictured from left, t the spot “where the burlesque legend strip meets the tease,” the Dusty Summers; Miss Burlesque Hall of Fame is Exotic World 2011 boldly smashing stereotypes Indigo Blue; Miss Exotic World 2010 Roxi of museums everywhere. Sterile walls A D’lite; Tempest Storm, and stoic guides are replaced by campy the Queen of Exotic costumes and cotton candy-colored Dancers; BHoF staff backdrops. Instead of priceless paintings member Buttercup; Las or artifacts encased in glass, visitors Vegas Mayor Carolyn Goodman; Miss Exotic interact with the vintage hand-me- World 2005 Michelle downs of burlesque sex symbols—like L’amour; BHoF board Jayne Mansfield's heart-shaped love seat member Melody and the oversized martini glass Dita Von Sweets; Marinka, also Teese made famous as a stage prop. known as Queen of Unveiled this past April, BHoF’s the Amazons; Best Boylesque winner 2015 newest incarnation is 3,000 square feet Matt Finish; BHoF of flirtatious fun celebrating the art Executive Director of the tease just a stone’s throw from Dustin Wax. the Las Vegas Strip. A major upgrade from its former space of just 200 square feet, the museum gives guests the rare playful props stood guard around an inground pool, hinting that this was no opportunity to peek under the skirt place for the straight-laced. of the burlesque—with everything After Lee’s death in 1990, fellow entertainer Dixie Evans continued her from autographed photos and corset- friend’s legacy, greeting guests in glittery gowns and feather boas, eventually clad mannequins to theater marquees adding an attraction that put the museum on the map—the Miss Exotic World and giant mounted posters from hit Pageant, a striptease contest where spectators could indulge their skin-bearing productions.