Canadian Army Redux: How to Achieve Better Outcomes Without Additional Resources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![1 Armoured Division (1940)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0098/1-armoured-division-1940-130098.webp)

1 Armoured Division (1940)]

7 September 2020 [1 ARMOURED DIVISION (1940)] st 1 Armoured Division (1) Headquarters, 1st Armoured Division 2nd Armoured Brigade (2) Headquarters, 2nd Armoured Brigade & Signal Section The Queen’s Bays (2nd Dragoon Guards) 9th Queen’s Royal Lancers 10th Royal Hussars (Prince of Wales’s Own) 3rd Armoured Brigade (3) Headquarters, 3rd Armoured Brigade & Signal Section 2nd Royal Tank Regiment 3rd Royal Tank Regiment (4) 5th Royal Tank Regiment 1st Support Group (5) Headquarters, 1st Support Group & Signal Section 2nd Bn. The King’s Royal Rifles Corps 1st Bn. The Rifle Brigade (Prince Consort’s Own) 1st Regiment, Royal Horse Artillery (H.Q., A/E & B/O Batteries, Royal Horse Artillery) 2nd Regiment, Royal Horse Artillery (H.Q., L/N & H/I Batteries, Royal Horse Artillery) Divisional Troops 1st Field Squadron, Royal Engineers 1st Field Park Troop, Royal Engineers 1st Armoured Divisional Signals, (1st County of London Yeomanry (Middlesex, Duke of Cambridge’s Hussars)), Royal Corps of Signals ©www.BritishMilitaryH istory.co.uk Page 1 7 September 2020 [1 ARMOURED DIVISION (1940)] NOTES: 1. A pre-war Regular Army formation formerly known as The Mobile Division. The divisional headquarters were based at Priory Lodge near Andover, within Southern Command. This was the only armoured division in the British Army at the outbreak of the Second World War. The division remained in the U.K. training and equipping until leaving for France on 14 May 1940. Initial elements of the 1st Armoured Division began landing at Le Havre on 15 May, being sent to a location south of Rouen to concentrate and prepare for action. -

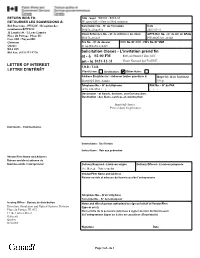

WESM - RFI/LOI RETOURNER LES SOUMISSIONS À: Weapons Effect System Modernization Bid Receiving - PWGSC / Réception Des Solicitation No

1 1 RETURN BIDS TO: Title - Sujet WESM - RFI/LOI RETOURNER LES SOUMISSIONS À: Weapons Effect System Modernization Bid Receiving - PWGSC / Réception des Solicitation No. - N° de l'invitation Date soumissions TPSGC W8476-216429/A 2021-03-11 11 Laurier St. / 11, rue Laurier Client Reference No. - N° de référence du client GETS Ref. No. - N° de réf. de SEAG Place du Portage, Phase III Core 0B2 / Noyau 0B2 W8476-216429 PW-$$QT-011-28148 Gatineau File No. - N° de dossier CCC No./N° CCC - FMS No./N° VME Quebec 011qt.W8476-216429 K1A 0S5 Bid Fax: (819) 997-9776 Solicitation Closes - L'invitation prend fin at - à 02:00 PM Eastern Standard Time EST on - le 2021-12-31 Heure Normale du l'Est HNE LETTER OF INTEREST F.O.B. - F.A.B. LETTRE D'INTÉRÊT Plant-Usine: Destination: Other-Autre: Address Enquiries to: - Adresser toutes questions à: Buyer Id - Id de l'acheteur Derby(QT Div), Sandra 011qt Telephone No. - N° de téléphone FAX No. - N° de FAX (873) 355-4982 ( ) ( ) - Destination - of Goods, Services, and Construction: Destination - des biens, services et construction: Specified Herein Précisé dans les présentes Comments - Commentaires Instructions: See Herein Instructions: Voir aux présentes Vendor/Firm Name and Address Raison sociale et adresse du fournisseur/de l'entrepreneur Delivery Required - Livraison exigée Delivery Offered - Livraison proposée See Herein – Voir ci-inclus Vendor/Firm Name and Address Raison sociale et adresse du fournisseur/de l'entrepreneur Telephone No. - N°de téléphone Facsimile No. - N° de télécopieur Issuing Office - Bureau de distribution Name and title of person authorized to sign on behalf of Vendor/Firm Detection, Simulation and Optical Systems Division (type or print) Place du Portage III, 8C2 Nom et titre de la personne autorisée à signer au nom du fournisseur/ 11 rue Laurier Street de l'entrepreneur (taper ou écrire en caractères d'imprimerie) Gatineau Quebec K1A 0S5 Signature Date Page 1 of - de 1 Weapon Effects Simulation Modernization Request for Information 1. -

THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN RANGERS, Octobre 2010

A-DH-267-000/AF-003 THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN RANGERS THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN RANGERS BADGE INSIGNE Description Description Gules a Dall ram's head in trian aspect Or all within De gueules à la tête d'un mouflon de Dall d'or an annulus Gules edged and inscribed THE ROCKY tournée de trois quarts, le tout entouré d'un anneau MOUNTAIN RANGERS in letters Or ensigned by the de gueules liséré d'or, inscrit THE ROCKY Royal Crown proper and environed by maple leaves MOUNTAIN RANGERS en lettres du même, sommé proper issuant from a scroll Gules edged and de la couronne royale au naturel et environné de inscribed with the Motto in letters Or. feuilles d'érable du même, le tout soutenu d'un listel de gueules liséré d’or et inscrit de la devise en lettres du même. Symbolism Symbolisme The maple leaves represent service to Canada and Les feuilles d'érable représentent le service au the Crown represents service to the Sovereign. The Canada, et la couronne, le service à la Souveraine. head of a ram or big horn sheep was approved for Le port de l'insigne à tête de bélier ou de mouflon wear by all independent rifle companies in the d'Amérique a été approuvé en 1899 pour toutes les Province of British Columbia in 1899. "THE ROCKY compagnies de fusiliers indépendantes de la MOUNTAIN RANGERS" is the regimental title, and Province de la Colombie-Britannique. « THE ROCKY "KLOSHE NANITCH" is the motto of the regiment, in MOUNTAIN RANGERS » est le nom du régiment, et the Chinook dialect. -

Specialization and the Canadian Forces (2003)

SPECIALIZATION AND THE CANADIAN FORCES PHILIPPE LAGASSÉ OCCASIONAL PAPER No. 40, 2003 The Norman Paterson School of International Affairs Carleton University 1125 Colonel By Drive Ottawa, Ontario K1S 5B6 Telephone: 613-520-6655 Fax: 613-520-2889 This series is published by the Centre for Security and Defence Studies at the School and supported by a grant from the Security Defence Forum of the Department of National Defence. The views expressed in the paper do not necessarily represent the views of the School or the Department of National Defence TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT 3 Introduction 4 Determinants of Force Structuring 7 Canadian Defence Policy 16 Specialization, Transformation and Canadian Defence 29 Conclusion 36 REFERENCES 38 ABOUT THE AUTHOR 40 2 ABSTRACT Canada is facing a force structuring dilemma. In spite of Ottawa’s desire to promote international peace and stability alongside the United States and the United Nations, Canada’s minimalist approaches to defence spending and capital expenditures are undermining the long-term viability of the Canadian Forces’ (CF) expeditionary and interoperable capabilities. Two solutions to this dilemma present themselves: increased defence spending or greater force structure specialization. Since Ottawa is unlikely to increase defence spending, specialization provides the only practical solution to the CF’s capabilities predicament. Though it would limit the number of tasks that the CF could perform overseas, specialization would maximize the output of current capital expenditures and preserve the CF’s interoperability with the US military in an age of defence transformation. This paper thus argues that the economics of Canadian defence necessitate a more specialized CF force structure. -

GAUTHIER John Louis

Gauthier, John Louis Private Algonquin Regiment Royal Canadian Infantry Corps C122588 John Louis Gauthier was born on Aug. 28, 1925 to French-Canadian parents, John Alfred Gauthier (1896-1983) and Clara Carriere (1900-1978) living in the Town of Renfrew, Ontario. The family also comprised James (1929-1941); Margaret (1932 died as an enfant); Blanche (1933-present) and Thomas (1937- present). Mr. Gauthier worked at the factory of the Renfrew Electric and Refrigeration Company. Jackie, as he was affectionately known, attended Roman Catholic elementary school and spent two years at Renfrew Collegiate Institute. After leaving high school, he went to work as a bench hand at the same factory as his father. In the summers, he was also a well-liked counsellor at the church youth camp in Lake Clear near Eganville, Ontario. Both his sister, Blanche, and brother, Thomas, recall Jackie’s comments when he decided to sign up for military at the age of 18 years old. “He told our mother that ‘Mom, if I don’t come back, you can walk down Main Street (in Renfrew) and hold your head high‘,” said Blanche. “In those days, men who didn’t volunteer to go overseas to war were called ‘zombies‘.” It was a common term of ridicule during the Second World War; Canadians were embroiled in debates about conscription or compulsory overseas military service. Many men had volunteered to go but others avoided enlistment. By mid-1943, the government was under pressure to force men to fight in Europe and the Far East. 1 Jackie Gauthier had enlisted on Oct. -

Small Arms Trainer Validation and Transfer of Training: C7 Rifle

L LL Small Arms Trainer Validation and Transfer of Training: C7 Rifle Stuart C. Grant Defence R&D Canada Technical Report DRDC Toronto TR 2013-085 December 2013 Limited D Small Arms Trainer Validation and Transfer of Training: C7 Rifle Stuart C. Grant DRDC, Toronto Research Centre Defence R&D Canada, Toronto Research Centre Technical Report DRDC Toronto TR 2013-085 December 2013 Principal Author Original signed by Stuart C. Grant Stuart C. Grant Defence Scientist Approved by Original signed by Linda Bossi Linda Bossi Section Head, Human Systems Integration Section Approved for release by Original signed by Joseph V. Baranski Joseph V. Baranski Chair, Knowledge and Information Management Committee, Chief Scientist In conducting the research described in this report, the investigators adhered to the policies and procedures set out in the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical conduct for research involving humans (2010) as issued jointly by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as represented by the Minister of National Defence, 2013 © Sa Majesté la Reine (en droit du Canada), telle que représentée par le ministre de la Défense nationale, 2013 Abstract …….. The Canadian Army uses the Small Arms Trainer (SAT) to support the use of infantry weapons. A trial was conducted at CFB Gagetown to validate the simulator and to determine how live and simulated fire should be used to prepare troops for the Personal Weapons Test Level 3 (PWT3). Six infantry platoons completed the range practices using either x all live fire; x all simulated fire; x simulated fire, completing all range practices twice; or x simulated fire for the first five range practices and live fire for the last three range practices. -

TRANSFORMING the BRITISH ARMY an Update

TRANSFORMING THE BRITISH ARMY An Update © Crown copyright July 2013 Images Army Picture Desk, Army Headquarters Designed by Design Studio ADR002930 | TRANSFORMING THE BRITISH ARMY 2013 TRANSFORMING THE BRITISH ARMY 2013 | 1 Contents Foreword 1 Army 2020 Background 2 The Army 2020 Design 3 Formation Basing and Names 4 The Reaction Force 6 The Adaptable Force 8 Force Troops Command 10 Transition to new Structures 14 Training 15 Personnel 18 Defence Engagement 21 Firm Base 22 Support to Homeland Resilience 23 Equipment 24 Reserves 26 Army Communication Strategic Themes 28 | TRANSFORMING THE BRITISH ARMY 2013 TRANSFORMING THE BRITISH ARMY 2013 | 1 Foreword General Sir Peter Wall GCB CBE ADC Gen Chief of the General Staff We have made significant progress in refining the detail of Army 2020 since it was announced in July 2012. It is worth taking stock of what has been achieved so far, and ensuring that our direction of travel continues to be understood by the Army. This comprehensive update achieves this purpose well and should be read widely. I wish to highlight four particular points: • Our success in establishing Defence Engagement as a core Defence output. Not only will this enable us to make a crucial contribution to conflict prevention, but it will enhance our contingent capability by developing our understanding. It will also give the Adaptable Force a challenging focus in addition to enduring operations and homeland resilience. • We must be clear that our capacity to influence overseas is founded upon our credibility as a war-fighting Army, capable of projecting force anywhere in the world. -

The Canadian Rangers: a “Postmodern” Militia That Works

DND photo 8977 THE GREAT WHITE NORTH THE GREAT Canadian Rangers travel by snowmobile in the winter and all terrain vehicles in the summer. Road access is limited in many areas and non-existent in others. THE CANADIAN RANGERS: A “POSTMODERN” MILITIA THAT WORKS by P. Whitney Lackenbauer The Centre of Gravity for CFNA is our positive While commentators typically cast the Canadian relationship with the aboriginal peoples of the North, Rangers as an arctic force – a stereotype perpetuated in this all levels of government in the three territories, and article – they are more accurately situated around the fringes all other government agencies and non-governmental of the country. Their official role since 1947 has been “to organizations operating North of 60. Without the provide a military presence in those sparsely settled northern, support, confidence, and strong working relationships coastal and isolated areas of Canada which cannot with these peoples and agencies, CFNA would be conveniently or economically be provided by other components unable to carry out many of its assigned tasks. of the Canadian Forces.” They are often described as the military’s “eyes and ears” in remote regions. The Rangers – Colonel Kevin McLeod, also represent an important success story for the Canadian former Commander Canadian Forces Forces as a flexible, inexpensive, and culturally inclusive Northern Area1 means of “showing the flag” and asserting Canadian sovereignty while fulfilling vital operational requirements. anada’s vast northern expanse and extensive They often represent the only CF presence in some of the coastlines have represented a significant least populated parts of the country, and serve as a bridge security and sovereignty dilemma since between cultures and between the civilian and military realms. -

A Historiography of C Force

Canadian Military History Volume 24 Issue 2 Article 10 2015 A Historiography of C Force Tony Banham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/cmh Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Tony Banham "A Historiography of C Force." Canadian Military History 24, 2 (2015) This Feature is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canadian Military History by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. : A Historiography of C Force FEATURE A Historiography of C Force TONY BANHAM Abstract: Following the Japanese invasion of Hong Kong in 1941, a small number of books covering the then Colony’s war experiences were published. Although swamped by larger and more significant battles, the volume of work has expanded in the years since and is no longer insignificant. This historiography documents that body of literature, examining trends and possible future directions for further study with particular respect to the coverage of C Force. h e f a t e o f the 1,975 men and two women of C Force, sent T to Hong Kong just before the Japanese invaded, has generated a surprising volume of literature. It was fate too that a Canadian, Major General Arthur Edward Grasett, was the outgoing commander of British troops in China— including the Hong Kong garrison— in mid-1941 (being replaced that August by Major General Christopher M altby of the Indian army), and fate that his determination that the garrison be reinforced would see a Briton, Brigadier John Kelburne Lawson, arrive from Canada in November 1941 as commander of this small force sent to bolster the colony’s defences. -

The Canadian Militia in the Interwar Years, 1919-39

THE POLICY OF NEGLECT: THE CANADIAN MILITIA IN THE INTERWAR YEARS, 1919-39 ___________________________________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board ___________________________________________________________ in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY __________________________________________________________ by Britton Wade MacDonald January, 2009 iii © Copyright 2008 by Britton W. MacDonald iv ABSTRACT The Policy of Neglect: The Canadian Militia in the Interwar Years, 1919-1939 Britton W. MacDonald Doctor of Philosophy Temple University, 2008 Dr. Gregory J. W. Urwin The Canadian Militia, since its beginning, has been underfunded and under-supported by the government, no matter which political party was in power. This trend continued throughout the interwar years of 1919 to 1939. During these years, the Militia’s members had to improvise a great deal of the time in their efforts to attain military effectiveness. This included much of their training, which they often funded with their own pay. They created their own training apparatuses, such as mock tanks, so that their preparations had a hint of realism. Officers designed interesting and unique exercises to challenge their personnel. All these actions helped create esprit de corps in the Militia, particularly the half composed of citizen soldiers, the Non- Permanent Active Militia. The regulars, the Permanent Active Militia (or Permanent Force), also relied on their own efforts to improve themselves as soldiers. They found intellectual nourishment in an excellent service journal, the Canadian Defence Quarterly, and British schools. The Militia learned to endure in these years because of all the trials its members faced. The interwar years are important for their impact on how the Canadian Army (as it was known after 1940) would fight the Second World War. -

Aboriginal Peoples in the Canadian Rangers, 1947-2005 P

CENTRE FOR MILITARY AND STRATEGIC STUDIES Calgary Papers in Military and Strategic Studies Occasional Paper Number 4, 2011 Canadian Arctic Sovereignty and Security: Historical Perspectives Edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer Calgary Papers in Military and Strategic Studies ISSN 1911-799X Editor DR. JOHN FERRIS Managing Editor: Nancy Pearson Mackie Cover: The Mobile Striking Force, an airportable and airborne brigade group designed as a quick reaction force for northern operations, was an inexpensive solution to the question of how Canada could deal with an enemy lodgement in the Arctic. During training exercises, army personnel from southern Canada learned how to survive and operate in the north. In this image, taken during Exercise Bulldog II in 1954, Inuk Ranger TooToo from Churchill, Manitoba relays information to army personnel in a Penguin. DND photo PC-7066. Canadian Arctic Sovereignty and Security: Historical Perspectives Occasional Paper Number 4, 2011 ISBN 978-1-55238-560-9 Centre for Military and Strategic Studies MacKimmie Library Tower 701 University of Calgary 2500 University Drive NW Calgary, AB T2N 1N4 Tel: 403.220.4030 / Fax: 403.282.0594 www.cmss.ucalgary.ca / [email protected] Copyright © Centre for Military and Strategic Studies, 2011 Permission policies are outlined on our website: http://cmss.ucalgary.ca/publications/calgarypapers Calgary Papers in Military and Strategic Studies Canadian Arctic Sovereignty and Security Historical Perspectives Edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer Contents Introduction p. whitney lackenbauer -

Military Despatches Vol 24, June 2019

Military Despatches Vol 24 June 2019 Operation Deadstick A mission vital to D-Day Remembering D-Day Marking the 75th anniversary of D-Day Forged in Battle The Katyusha MRLS, Stalin’s Organ Isoroku Yamamoto The architect of Pearl Harbour Thank your lucky stars Life in the North Korean military For the military enthusiast CONTENTS June 2019 Page 62 Click on any video below to view Page 14 How much do you know about movie theme songs? Take our quiz and find out. Hipe’s Wouter de The old South African Goede interviews former Defence Force used 28’s gang boss David a mixture of English, Williams. Afrikaans, slang and Thank your lucky stars techno-speak that few Serving in the North Korean Military outside the military could hope to under- 32 stand. Some of the terms Features were humorous, some Rank Structure 6 This month we look at the Ca- were clever, while others nadian Armed Forces. were downright crude. Top Ten Wartime Urban Legends Ten disturbing wartime urban 36 legends that turned out to be A matter of survival Part of Hipe’s “On the fiction. This month we’re looking at couch” series, this is an 10 constructing bird traps. interview with one of Special Forces - Canada 29 author Herman Charles Part Four of a series that takes Jimmy’s get together Quiz Bosman’s most famous a look at Special Forces units We attend the Signal’s Associ- characters, Oom Schalk around the world. ation luncheon and meet a 98 47 year old World War II veteran.