Tilburg University Alternative Investment Fund Industry in China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Les Politiques De Développement Régional D'une Zone Périphérique

Les politiques de développement régional d’une zone périphérique chinoise, le cas de la province de Hainan Sébastien Goulard To cite this version: Sébastien Goulard. Les politiques de développement régional d’une zone périphérique chinoise, le cas de la province de Hainan . Science politique. EHESS, 2014. Français. tel-01111893 HAL Id: tel-01111893 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01111893 Submitted on 31 Jan 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License ÉCOLE DES HAUTES ÉTUDES EN SCIENCES SOCIALES Thèse en vue de l‟obtention du Doctorat en socio-économie du développement Sébastien GOULARD Les politiques de développement régional d’une zone périphérique chinoise, le cas de la province de Hainan Thèse dirigée par François GIPOULOUX, directeur de recherche au CNRS Présentée et soutenue publiquement à l‟École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales à Paris, le 18 décembre 2014. Membres du jury : François GIPOULOUX, directeur de recherche, -

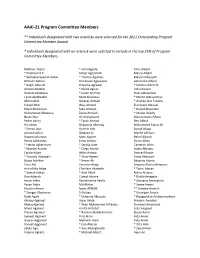

AAAI-21 Program Committee Members

AAAI-21 Program Committee Members ** Individuals designated with two asterisks were selected for the 2021 Outstanding Program Committee Member Award. * Individuals designated with an asterisk were selected to include in the top 25% of Program Committee Members. Mathieu ’Aquin * John Agosta Chris Alberti * Prathosh A P Forest Agostinelli Marco Alberti * Sathyanarayanan Aakur * Thomas Agotnes Marjan Albooyeh Mohsen Abbasi Don Joven Agravante Alexandre Albore * Ralph Abboud Priyanka Agrawal * Stefano Albrecht Ahmed Abdelali * Derek Aguiar Vidal Alcazar Ibrahim Abdelaziz * Julien Ah-Pine Huib Aldewereld Tarek Abdelzaher Ranit Aharonov * Martin Aleksandrov Afshin Abdi Sheeraz Ahmad * Andrea Aler Tubella S Asad Abdi Wasi Ahmad Francesco Alesiani Majid Abdolshah Saba Ahmadi * Daniel Alexander Mohammad Abdulaziz Zahra Ahmadi * Modar Alfadly Naoki Abe Ali Ahmadvand Gianvincenzo Alfano Pedro Abreu * Faruk Ahmed Ron Alford Rui Abreu Shqiponja Ahmetaj Mohammed Eunus Ali * Erman Acar Hyemin Ahn Daniel Aliaga Avinash Achar Qingyao Ai Malihe Alikhani Rupam Acharyya Marc Aiguier Rahaf Aljundi Panos Achlioptas Esma Aimeur Oznur Alkan * Hanno Ackermann * Sandip Aine Cameron Allen * Maribel Acosta * Diego Aineto Adam Allevato Carole Adam Akiko Aizawa Amine Allouah * Sravanti Addepalli * Nirav Ajmeri Faisal Almutairi Bijaya Adhikari * Kenan Ak Eduardo Alonso Yossi Adi Yasunori Akagi Amparo Alonso-Betanzos Aniruddha Adiga Charilaos Akasiadis * Tansu Alpcan * Somak Aditya * Alan Akbik Mario Alviano Don Adjeroh Cuneyt Akcora * Daichi Amagata Aaron Adler Ramakrishna -

Dwelling in Shenzhen: Development of Living Environment from 1979 to 2018

Dwelling in Shenzhen: Development of Living Environment from 1979 to 2018 Xiaoqing Kong Master of Architecture Design A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2020 School of Historical and Philosophical Inquiry Abstract Shenzhen, one of the fastest growing cities in the world, is the benchmark of China’s new generation of cities. As the pioneer of the economic reform, Shenzhen has developed from a small border town to an international metropolis. Shenzhen government solved the housing demand of the huge population, thereby transforming Shenzhen from an immigrant city to a settled city. By studying Shenzhen’s housing development in the past 40 years, this thesis argues that housing development is a process of competition and cooperation among three groups, namely, the government, the developer, and the buyers, constantly competing for their respective interests and goals. This competing and cooperating process is dynamic and needs constant adjustment and balancing of the interests of the three groups. Moreover, this thesis examines the means and results of the three groups in the tripartite competition and cooperation, and delineates that the government is the dominant player responsible for preserving the competitive balance of this tripartite game, a role vital for housing development and urban growth in China. In the new round of competition between cities for talent and capital, only when the government correctly and effectively uses its power to make the three groups interacting benignly and achieving a certain degree of benefit respectively can the dynamic balance be maintained, thereby furthering development of Chinese cities. -

Au Bord De L'eau

Au bord de l'eau Au bord de l'eau (chinois simplifié : 水浒传 ; chinois traditionnel : 水滸傳 ; pinyin : Shuǐ hǔ Zhuàn ; Wade : Shui³ hu³ Zhuan⁴, EFEO Chouei-hou tchouan, littéralement « Le Récit e des berges ») est un roman d'aventures tiré de la tradition orale chinoise, compilé et écrit par plusieurs auteurs, mais attribué généralement à Shi Nai'an (XIV siècle). Il relate les Au bord de l'eau exploits de cent huit bandits, révoltés contre la corruption du gouvernement et des hauts fonctionnaires de la cour de l'empereur. Auteur Shi Nai'an Ce roman fait partie des quatre grands romans classiques de la dynastie Ming, avec l'Histoire des Trois Royaumes, La Pérégrination vers l'Ouest et Le Rêve dans le Pavillon Rouge. Pays Chine Sa notoriété est telle que de nombreuses versions ont été rédigées. On peut comparer sa place dans la culture chinoise à celle des Trois Mousquetaires d'Alexandre Dumas en France, Genre roman ou des aventures de Robin des Bois en Angleterre. L'ouvrage est la source d'innombrables expressions littéraires ou populaires, et de nombreux personnages ou passages du livre servent à symboliser des caractères ou des situations (comme Lin Chong, seul dans la neige, pour dépeindre la rectitude face à l'adversité, ou Li Kui, irascible et violent mais dévoué à Version originale sa mère impotente, pour signaler un homme dont les défauts évidents masquent des qualités cachées). On retrouve, souvent sous forme de pastiche, des scènes connues dans des Langue chinois vernaculaire publicités, des dessins animés, des clips vidéo. L'illustration de moments classiques de l'ouvrage est très fréquente en peinture. -

Eminent Nuns

Bu d d h i s m /Ch i n e s e l i t e r a t u r e (Continued from front flap) g r a n t collections of “discourse records” (yulu) Of related interest The seventeenth century is generally of seven officially designated female acknowledged as one of the most Chan masters in a seventeenth-century politically tumultuous but culturally printing of the Chinese Buddhist Buddhism and Taoism Face to Face creative periods of late imperial Canon rarely used in English-language sC r i p t u r e , ri t u a l , a n d iC o n o g r a p h i C ex C h a n g e in me d i e v a l Ch i n a Chinese history. Scholars have noted scholarship. The collections contain Christine Mollier the profound effect on, and literary records of religious sermons and 2008, 256 pages, illus. responses to, the fall of the Ming on exchanges, letters, prose pieces, and Cloth ISBN: 978-0-8248-3169-1 the male literati elite. Also of great poems, as well as biographical and interest is the remarkable emergence autobiographical accounts of various “This book exemplifies the best sort of work being done on Chinese beginning in the late Ming of educated kinds. Supplemental sources by Chan religions today. Christine Mollier expertly draws not only on published women as readers and, more im- monks and male literati from the same canonical sources but also on manuscript and visual material, as well portantly, writers. -

Did Government Decentralization Cause China's Economic Miracle?

Did government decentralization cause China’s economic miracle? a b Hongbin Cai Daniel Treisman Many scholars attribute China’s remarkable economic performance since 1978 in part to the country’s political and fiscal decentralization. Political decentralization is said to have stimulated local policy experiments and restrained predatory central interventions. Fiscal decentralization is thought to have motivated local officials to promote development and harden enterprises’ budget constraints. The locally diversified structure of the pre- reform economy is said to have facilitated liberalization. We examine these arguments and find that none establishes a convincing link between decentralization and China’s successes. We suggest an alternative view of the reform process, in which growth-enhancing policies emerged from competition between pro- and anti-market factions in Beijing. a Department of Economics, University of California, Los Angeles b Department of Political Science, University of California, Los Angeles, 4289 Bunche Hall, Los Angeles CA 90095-1472 March 2006 We thank Richard Baum, Tom Bernstein, Dorothy Solinger, Bo Li, Dali Yang, Li-An Zhou, and James Tong for comments and suggestions. 1 Introduction What roles have political and fiscal decentralization played in China’s economic reforms and in the remarkable boom they fostered? Since the late 1970s, China has liberalized most prices, de- collectivized agriculture, and integrated into world markets. These changes fueled an unprecedented period of growth, with GDP per capita rising from $674 in 1978 to $5,085 in 2004 (in PPP-adjusted 2000 dollars).1 Scholars have attributed this economic miracle to many causes— recovery from the Cultural Revolution, initial underdevelopment, and a rich diaspora, to name a few. -

The Water Margin Podcast. This Is Episode 54. Last Time, Song Jiang

Welcome to the Water Margin Podcast. This is episode 54. Last time, Song Jiang and his two guards narrowly escaped becoming soylent green in a black tavern and ended up befriending that tavern keeper and his gang of smuggler buddies. Then, farther down the road, they unknowingly ran afoul of some local bullies and found themselves fleeing said bullies at night. Fortunately, they found a boat to ferry them across the Sundown River, leaving their pursuers behind. Unfortunately, the boat stopped in the middle of the river, and the boatman, a guy who called himself Zhang, demanded that they either submit themselves to his blade or drown themselves in the roaring river. Song Jiang begged and pleaded, offering to give the guy all their money and clothes, but the guy was like, “Well, I’m going to get all that anyway. So hurry up and get naked and jump into the water already.” Things were not looking good. Caught between death by stabbing or death by drowning, Song Jiang and his guards picked the latter. Clutching each other, they were just about to jump when suddenly, they heard the sound of water splashing. They turned and saw another boat speeding toward them from upriver. In the boat stood three men. One of them stood at the head of the boat with a pitchfork in hand, while the other two were in the back, rowing hard. Before you knew it, they were near Song Jiang’s boat. “Who is that boatman over there?” the man at the head of the oncoming boat shouted. -

Regionale Reformpolitik in China. Die Modernisierung Von Staat Und

Center for East Asian and Pacific Studies Trier University, Germany China Analysis No. 18 (November 2002) www.chinapolitik.de Regionale Reformpolitik in China: Die Modernisierung von Staat und Verwaltung Dr. Jörn-Carsten Gottwald Center for East Asian and Pacific Studies Trier University, FB III 54286 Trier, Germany E-mail: [email protected] 1. Einleitung 1.1 Bestimmung staatlicher Kernkompetenzen 1.2 Die Traditionen regionaler Reformkonzepte 2. Hainan als Modell1987/88 2.1 Politische Reformen 2.1.1 Kernaufgaben der Provinzregierung 2.1.2 „Kontrolle“ 2.1.3 „Entwicklung“ 2.2 Das Konzept „ Xiao Zhengfu“ 2.2.1 Lean administration 2.2.2 Individuelle Freiheiten 2.2.3 Wirtschaftliche Öffnung 2.2.4 Was nicht reformiert werden darf.... 3. Von der Theorie zur Praxis 3.1 Auf der Suche nach einer kleinen Regierung 3.2 Kurskorrekturen 3.3 Ein rasches Comeback 3.4 Erneute Kurskorrekturen 3.5 Neue Schwerpunkte 4. Fazit: Administrative Reformen als Stückwerk 1 1. Einleitung Im November 2002 wird die Kommunistische Partei Chinas eine Ära des Übergangs in der chinesischen Politik zu einem vorläufigen Abschluss bringen. Unabhängig davon, wie weit sich die Führungsspitze um den Generalsekretär der KPC und Staatspräsiden- ten Jiang Zemin, Premierminister Zhu Rongji und den Vorsitzenden des Nationalen Volkskongresses Li Peng aus der tatsächlichen Entscheidungsfindung zurückziehen wird, lässt sich das Ende einer Phase der chinesischen Politik konstatieren, in der wich- tige neue Reformschritte eingeleitet und umgesetzt wurden. Ein zentrales Vorhaben der 1990er Jahre war die Suche nach einer Modernisierung des Staats- und Parteiapparates, die die Voraussetzung für eine erfolgreiche Fortführung der wirtschaftlichen und gesell- schaftlichen Modernisierung sowie für eine erfolgreiche Integration der VR China in die Weltwirtschaftsordnung bilden sollte. -

Automation Date/Time Tuesday, 3 June 2008 / 10:30 - 12:30 Hrs 1 ) ( Day Venue Changi Rm 1 Session Chair(S) LIU Tien-I & Kenne JEAN-PIERRE

Technical Programme Session TUE1-1 (Aut) - Automation Date/Time Tuesday, 3 June 2008 / 10:30 - 12:30 hrs 1 ) ( Day Venue Changi Rm 1 Session Chair(s) LIU Tien-I & Kenne JEAN-PIERRE 10:30 - 10:50 TUE1-1 (Aut)-1 conf130a129 Pg No. On-Line Monitoring and Diagnosis of Tapping Process Using Neuro Fuzzy System 71 Tien-I LIU, Junyi LEE and Gurinder Singh GILL 10:50 - 11:10 TUE1-1 (Aut)-2 conf130a170 A Replacement Policy of Deteriorating Production Systems Subject to Imperfect Repairs 71 F. I. DEHAYEM NODEM, J.P. KENNE and A. GHARBI 11:10 - 11:30 TUE1-1 (Aut)-3 conf130a333 Application of Neural Network Data Fusion Algorithm in Measurement Circuit 71 Xiaoyong NI, Dianhong WANG and Hongjian ZHANG 11:30 - 11:50 TUE1-1 (Aut)-4 conf130a688 71 An Adaptive Annealing Genetic Algorithm for Workshop Daily Operation Planning Min LIU and Li BAI 11:50 - 12:10 TUE1-1 (Aut)-5 conf130a803 One Kind of Water Level Monitor 72 PENG Xuange, LI Peipei and HUANG Chunying 12:10 - 12:30 TUE1-1 (Aut)-6 conf130a986 Optimization Method of Short Life Cycle Product Supply Chain Network with Recycle 72 Flow and Dispersed Markets Xili CHEN, Yenkai HUANG and Tomohiro MURATA 12:30 - 12:50 TUE1-1 (Aut)-7 conf130a356 Design of Information Display and Control Instrument Based on SoC for AIS and GPRS 72 Monitoring System WANG Ershen, ZHANG Shufang, HU Qing and LIANG Lifang Session TUE1-2 (CI-1) - Computational Intelligence-1 Date/Time Tuesday, 3 June 2008 / 10:30 - 12:30 hrs Venue Changi Rm 2 Session Chair(s) LI Yongzhong 10:30 - 10:50 TUE1-2 (CI-1)-1 conf130a108 Pg No. -

National Report on Habs in China

China-1 National Report on HABs in China China-2 Table of Content I. INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................... 4 1. Definition of red tide in China........................................................................... 5 2. Present situation of HABs in China................................................................... 5 3. Marine and coastal environment of NOWPAP region in China ....................... 9 II. DATA AND INFORMATION USED ...................................................................... 12 1. Situation of HAB Occurrence.......................................................................... 12 1.1 Red tide .......................................................................................................... 12 1.2 Toxin-producing Plankton ............................................................................. 12 2. Monitoring....................................................................................................... 13 3. Progress of Researches and Studies to Cope with HABs................................ 13 4. Literature Including Newly Obtained Information.......................................... 13 5. Training Activities to Cope with HABs .......................................................... 13 6. National Priority to Cope with HABs ............................................................. 13 7. Suggested Activity for the NOWPAP Region................................................. 13 III. RESULTS................................................................................................................ -

China Perspectives, 2012/4 | 2012 Erik Kjeld Brødsgaard, Hainan – State, Society, and Business in a Chinese Pro

China Perspectives 2012/4 | 2012 Chinese Women: Becoming Half the Sky? Erik Kjeld Brødsgaard, Hainan – State, Society, and Business in a Chinese Province London, Routledge, 2009, 190 pp. Hiav-yen Dam Translator: N. Jayaram Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/6061 DOI: 10.4000/chinaperspectives.6061 ISSN: 1996-4617 Publisher Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Printed version Date of publication: 7 December 2012 Number of pages: 78-79 ISSN: 2070-3449 Electronic reference Hiav-yen Dam, « Erik Kjeld Brødsgaard, Hainan – State, Society, and Business in a Chinese Province », China Perspectives [Online], 2012/4 | 2012, Online since 01 December 2012, connection on 22 September 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/6061 ; DOI : https://doi.org/ 10.4000/chinaperspectives.6061 This text was automatically generated on 22 September 2020. © All rights reserved Erik Kjeld Brødsgaard, Hainan – State, Society, and Business in a Chinese Pro... 1 Erik Kjeld Brødsgaard, Hainan – State, Society, and Business in a Chinese Province London, Routledge, 2009, 190 pp. Hiav-yen Dam Translation : N. Jayaram 1 This work by Kjeld Erik Brødsgaard, professor and director of the Asia Research Center, Copenhagen Business School, rests on a detailed study of Hainan Province in the reform era to paint a vast picture touching on relations between central authorities and provincial and local ones, the island’s economic development strategies, and administrative reforms in China, as well as relations between the state and society. Given the rarity of studies on Hainan Island, especially in the fields of politics and economics, as well as on its recent development, this book represents a major contribution. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

1/2006 Data Supplement PR China Hong Kong SAR Macau SAR Taiwan CHINA aktuell Journal of Current Chinese Affairs Data Supplement People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax:(040)4107945 Contributors: Uwe Kotzel Dr. Liu Jen-Kai Christine Reinking Dr. Günter Schucher Dr. Margot Schüller Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU JEN-KAI 3 The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC LIU JEN-KAI 22 Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership LIU JEN-KAI 27 PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries LIU JEN-KAI 45 PRC Laws and Regulations LIU JEN-KAI 50 Hong Kong SAR Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 54 Macau SAR Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 57 Taiwan Political LIU JEN-KAI 59 Bibliography of Articles on the PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, and on Taiwan UWE KOTZEL / LIU JEN-KAI / CHRISTINE REINKING / GÜNTER SCHUCHER 61 CHINA aktuell Data Supplement - 3 - 1/2006 The Leading Group for Fourmulating a National Strategy on Intellectual Prop- CHINESE COMMUNIST erty Rights was established in January 2005. The Main National (ChiDir, p.159) PARTY The National Disaster-Reduction Commit- tee was established on 2 April 2005. (ChiDir, Leadership of the p.152) CCP CC General Secretary China National Machinery and Equip- Hu Jintao 02/11 PRC ment (Group) Corporation changed its name into China National Machinery In- dustry Corporation (SINOMACH), begin- POLITBURO Liu Jen-Kai ning 8 September 2005.