COMMUNITY CONSERVATION PLAN Colgate Prairie Important Bird Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 31 S T Annual

THE 31ST ANNUAL NOVEMBER 10, 2020 NOVEMBER 10, 2020 MASTER OF CEREMONIES Mary Taylor-Ash CEO Tourism Saskatchewan PRESENTER Norm Beug Chair Tourism Saskatchewan Board of Directors 2 NOVEMBER 10, 2020 SASKATCHEWAN TOURISM AWARDS OF EXCELLENCE More than 30 years ago, Saskatchewan’s tourism sector began paying special tribute to leadership and achievement in the industry – to businesses and individuals who made exceptional contributions to tourism and demonstrated that success and fulfilment come with being true to your dreams, proud of your home and eager to treat guests to remarkable Saskatchewan experiences. The Saskatchewan Tourism Awards of Excellence Gala has become a yearly showcase of achievement, bringing together representatives from every corner of the province and from a diverse range of businesses and attractions to celebrate the accomplishments of their colleagues in the industry. Originally scheduled to take place on April 2 in Regina, the 31st annual event was cancelled, along with the HOST Saskatchewan Conference, due to the COVID-19 pandemic. With the cancellation of both industry gatherings, the announcement of the 12 Saskatchewan Tourism Awards of Excellence recipients and three Tourism Builders was postponed. Through the use of technology and adoption of a new virtual format, members of Saskatchewan’s tourism industry are now able to gather from afar to honour those outstanding businesses and people who have gone above and beyond to deliver superior service and experiences. Join the celebration as the Saskatchewan Tourism Awards of Excellence shine a spotlight on the commitment and hard work of veteran operators, as well as the innovative spirit of young entrepreneurs, and broaden understanding of efforts that yield success and, ultimately, position Saskatchewan as a more inviting and competitive destination. -

Going Places • Summer 2019 • 1

Going Places • Summer 2019 • 1 Summer 2019 2 6 11 18 SASKSECRETS SPORTS TOP FIVE TIPS FOR COMPLETING DESTINATION RECONCILIATION AND NEW LOOK AN AWARD NOMINATION DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY DIVERSITY ADDRESSED IN LAUNCHES FRAMEWORK WDM INCLUSIVITY REPORT TO ENRICH AND GROW TOURISM 2 • Going Places • Summer 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS Editor SaskSecrets sports new look ..............................................2 New funding pilot programs accepting applications Susan Parkin Message from the CEO .........................................................3 on October 1-November 15 .............................................11 Tourism Saskatchewan Tourism and jobs provide focus for World STEC News 189 - 1621 Albert Street Tourism Day ..............................................................................3 Tourism Workplace Leadership Conference Regina, Saskatchewan Saskatchewan increasingly attracts U.S. anglers focuses on tourism careers ...............................................12 Canada S4P 2S5 and hunters ..............................................................................4 Ashley Stone receives Tourism Phone: 306-787-2927 Message from the Chair .......................................................5 Ambassador Award .............................................................12 Fax: 306-787-6293 Tourism Saskatchewan releases 2018-2019 Introducing Amanda Ruller, I Heart Tourism Email: [email protected] Annual Report ..........................................................................5 influencer ................................................................................12 -

Tourism Saskatchewan 2017-2018 Annual Report $2.37 Billion in Travel Expenditures

Tourism Saskatchewan 2017-2018 Annual Report $2.37 billion in travel expenditures 13.6 million visits to and within Saskatchewan 1.4 billion advertising and marketing-generated impressions 67,200 residents employed in tourism 4,200 Saskatchewan tourism products and services Cover image: Fort Walsh National Historic Site Vision: A vibrant entrepreneurial tourism industry offering year-round compelling and memorable Saskatchewan experiences mission: Connect people with quality Saskatchewan experiences and advance the development of successful tourism operations Night sky over Meacham 2 Tourism Saskatchewan 2017-2018 Annual Report Letter of Transmittal His Honour, The Honourable W. Thomas Molloy Lieutenant Governor of the Province of Saskatchewan May it Please Your Honour: With respect, I submit Tourism Saskatchewan’s Annual Report for the fiscal period ending March 31, 2018. In compliance with The Tourism Saskatchewan Act , this document outlines the corporation’s business activities and includes audited financial statements. Gene Makowsky Minister Responsible for Tourism Saskatchewan Introduction This annual report contains information about Government Direction for 2017-18: Meeting the Tourism Saskatchewan’s activities during the past Challenge, The Saskatchewan Plan for Growth fiscal year (April 1, 2017 to March 31, 2018), along – Vision 2020 and Beyond , throne speeches and with financial statements for that period. other statements. The purpose of the document is to report to public The information contained within demonstrates and elected -

A Guide to Community Tourism Planning in Nova Scotia

A Guide to Community Tourism Planning in Nova Scotia Prepared by: THE ECONOMIC PLANNING GROUP of Canada Halifax, Nova Scotia COPYRIGHT ©2005 by Her Majesty the Queen in right of the Province of Nova Scotia All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without the prior written consent of The Province of Nova Scotia. The publisher is not engaged in rendering legal, accounting or other professional advice. If legal advice or expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought. The information and analysis contained herein is intended to be general and represents the research of the authors and should in no way be construed as being definitive or as being official or unofficial policy of any government body. Any reliance on the Guide shall be at the reader’s own risk. Table of Contents SECTION 1: INTRODUCTION ..................................................... 1 1.1 Purpose of the Guide ........................................................... 1 1.2 Contents of the Manual.......................................................... 2 1.3 Why Should your Community have a Tourism Plan? .................................. 3 SECTION 2: THE TOURISM INDUSTRY ............................................ 5 2.1 What is Tourism?.............................................................. 5 2.2 The International and National Context............................................. 6 International Travel and Tourism .......................................... 6 Tourism in Canada..................................................... -

Tourism Business Development and Financing Guide

TOURISM BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT AND FINANCING GUIDE GUIDE FOR TOURISM BUSINESSES FIFTH EDITION Tourism Business Development and Financing Guide TOURISM BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT AND FINANCING GUIDE Tourism Saskatchewan is pleased to deliver It is our hope that this guide will answer many another development tool for the tourism of your questions and help you avoid potential industry. This booklet provides a detailed roadblocks. Please keep in mind that planning approach that can be used to assist in throughout the course of planning and bringing the expansion of an existing tourism venture, or to life a new tourism initiative, you are invited the creation of a new tourism business. and encouraged to keep in close contact with our Industry Development branch, so that we In 2004, our industry generated over $1.4 may provide any additional assistance possible. billion in tourist activity, resulting from urban, rural, and northern visitor experiences. Tourism continues to be the fastest-growing economic Darryl McCallum sector in our province. Sound, effective business Director development is critical to sustaining this growth Industry Development Branch and increasing visitor expenditures. Further development of our tourism economy in Saskatchewan is greatly dependent upon strong and healthy tourism businesses. Tourism Saskatchewan wishes to express our appreciation for assistance with this publication to the following: 1 Tourism Business Development and Financing Guide TABLE OF CONTENTS PART ONE: THE DEVELOPMENT PROCESS . .4 PART TWO: SOURCES OF FINANCING FOR BUSINESSES IN THE TOURISM INDUSTRY . .29 INTRODUCTION . .4 INTRODUCTION . .29 CHAPTER ONE . .5 DEFINING THE PROJECT: Markets, Resources CHAPTER ELEVEN . .30 and Development INTERNAL SOURCES OF FINANCING (a) Owners – proprietors, partners, CHAPTER TWO . -

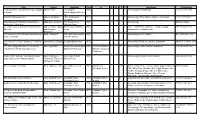

Title Author Publisher Date in V. Iss. # C. Key Words Call Number

Title Author Publisher Date In V. Iss. # C. Key Words Call Number Field Manual for Avocational Archaeologists Adams, Nick The Ontario 1994 1 Archaeology, Methodology CC75.5 .A32 1994 in Ontario Archaeological Society Inc. Prehistoric Mesoamerica Adams, Richard E. Little, Brown and 1977 1 Archaeology, Aztec, Olmec, Maya, Teotihuacan F1219 .A22 1991 W. Company Lithic Illustration: Drawing Flaked Stone Addington, Lucile R. The University of 1986 Archaeology 000Unavailable Artifacts for Publication Chicago Press The Bark Canoes and Skin Boats of North Adney, Edwin Tappan Smithsonian Institution 1983 1 Form, Construction, Maritime, Central Canada, E98 .B6 A46 1983 America and Howard I. Press Northwestern Canada, Arctic Chappelle The Knife River Flint Quarries: Excavations Ahler, Stanley A. State Historical Society 1986 1 Archaeology, Lithic, Quarry E78 .N75 A28 1986 at Site 32DU508 of North Dakota The Prehistoric Rock Paintings of Tassili N' Mazonowicz, Douglas Douglas Mazonowicz 1970 1 Archaeology, Rock Art, Sahara, Sandstone N5310.5 .T3 M39 1970 Ajjer The Archeology of Beaver Creek Shelter Alex, Lynn Marie Rocky Mountain Region 1991 Selections form the 3 1 Archaeology, South Dakota, Excavation E78 .S63 A38 1991 (39CU779): A Preliminary Statement National Park Service Division of Cultural Resources People of the Willows: The Prehistory and Ahler, Stanley A., University of North 1991 1 Archaeology, Mandan, North Dakota E99 .H6 A36 1991 Early History of the Hidatsa Indians Thomas D. Thiessen, Dakota Press Michael K. Trimble Archaeological Chemistry -

National Aboriginal Tourism Research Project 2015

NATIONAL ABORIGINAL TOURISM RESEARCH PROJECT 2015 Economic Impact of Aboriginal Tourism in Canada April 2015 O’Neil Marketing & Consulting Beverley O’Neil, Dr. Peter Williams, Krista Morten, Dr. Roslyn Kunin, Lee Gan Brian Payer Economic Impact of Aboriginal Tourism in Canada 2015 About ATAC ATAC was borne from industry leaders that were involved with Aboriginal Tourism Team Canada (ATTC). First, ATAC operated as an informal group under the name the Aboriginal Tourism Marketing Circle (ATMC), then in summer 2014, formerly established as Aboriginal Tourism Association of Canada. Over 20 Aboriginal tourism industry organizations and government representatives from across Canada are party to ATAC by signatory to a 2002 Memorandum of Understanding (MOU). Through a unified Aboriginal tourism industry voice, ATAC focuses on creating partnerships between associations, organizations, government departments and industry leaders from across Canada to support the growth of Aboriginal tourism in Canada. The Advisory Committee Great Appreciation to the project Advisory Committee members: Keith Henry, Aboriginal Tourism Assn of BC (AtBC) (Chair) Carole Bellefleur, Tourisme Autochtone Québec Patricia Dunnet, Metepenagiag Heritage Park Trina, Mather-Simard, Aboriginal Experiences Jeff Provost, Eastside Aboriginal Sustainable Tourism Inc. Dana Soonias, Wanuskewin Heritage Park Special Thanks Much appreciation and thanks to the project funder – Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada. The Project Team The project team was led by O’Neil Marketing & Consulting, a fully owned Aboriginal consulting business. The principle, Beverley O’Neil is a citizen of the Ktunaxa Nation and has more than 25 years in Aboriginal community economic development, tourism and research. The project team consisted of Beverley O’Neil (Contract/Lead), Dr. -

Saskatchewan Party Platform

We faced the pandemic - together. Then we reopened our economy - together. And now, we will build and recover - together. Our province is well positioned for a strong recovery. The Saskatchewan Party has the best plan to lead that strong recovery and the best plan to make life more affordable for everyone. Our Plan for a Strong Saskatchewan will drive Saskatchewan’s economic recovery and cre- ate jobs. We will lower power bills for homeowners, renters, farmers and businesses. We will help with the cost of home renovations. We will build hospitals, schools, highways and other important infrastructure projects. And we will reduce taxes on small businesses. Our Plan for a Strong Saskatchewan will make life more affordable for everyone - families, students, seniors, homeowners and others. And Our Plan for a Strong Saskatchewan will see the provincial budget balanced by 2024. Today, Saskatchewan is much stronger than when the NDP was in government. The NDP drove people, jobs and opportunities out of Saskatchewan. They closed 52 hospitals, 176 schools, and 1200 long-term care beds for seniors. Imagine how much worse the NDP would be for our economy now. Let’s never go back to that. The Saskatchewan Party has a plan for a strong recovery and a strong Saskatchewan. It’s a plan for: A strong economy and more jobs Strong communities Strong families Building highways, schools and hospitals Making life more affordable for families, seniors and young people On Monday, October 26, join us in voting for a strong economy, a strong recovery and a strong -

2010-2011 Annual Report

2010 - 2011 ANNUAL REPORT PROGRESS PROGRESS 100 - 1445 Park Street Regina, SK S4N 4C5 Phone: 306.780.9231 Toll-free: 1.800.563.2555 Fax: 306.780.9257 Website: www.spra.sk.ca 2 About SPRA Our Vision 2010 - 2011 SPRA We are the leader for a parks and recreation network that builds healthy active communities in Saskatchewan. Board of Directors SPRA’s volunteer Board of Directors govern and set the policies by which SPRA is guided. Our Mission We provide leadership and support to enhance the quality of President – Darrell Lessmeister the parks and recreation network. Director at Large – Mimi Lodoen Director at Large – Mike Powell Director at Large – Corrine Galarneau Our Roles Director at Large – Clint McConnell • Training Director for Cities – Jasmine Jackman • Education Director for Towns – Mike Schwean • Advocacy Director for Villages – Clive Craig • Funding Director for the North – Sandy Rediron (missing from photo) • Information management • Research • Networking Our Ends SPRA’s six Ends define what results we hold ourselves accountable for achieving, and for what audience. Trends, challenges, emerging opportunities and the core elements contributing to the success of the organization, along with member needs, have all shaped creation of the Ends. End 1 The parks and recreation network is coordinated End 2 There is a strong recreation component throughout the Province End 3 The parks and recreation network is supported End 4 The network advocates for parks and recreation in Saskatchewan End 5 Parks and open spaces are supported Supported by End 6 Recreation facilities are supported 3 President and CEO Report 2010 was a significant year in the history of the Saskatchewan Parks and Recreation Association. -

Radisson Lake Important Bird Area

COMMUNITY CONSERVATION PLAN for the Radisson Lake Important Bird Area March 2001 Josef K. Schmutz Community Conservation Planner Important Bird Areas Program Nature Saskatchewan c/o Centre for Studies in Agriculture, Law and Environment (CSALE) 51 Campus Drive, University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, SK, S7N 5A8 Tel. 306-966-2410 FAX 306-966-8894 E-mail: [email protected] Cover photo: The three Whooping Cranes were part of a group of five feeding in a barley field 5 km northwest of Radisson Lake in October 1998. When the three cranes flew to a nearby pond to drink, Brian Johns managed to take this photograph. Brian suspects that the three are subadults. The two in dance posture may be pairing, a process that can take years to complete. 5.2 Historical land use...................... 19 5.3 Current land use........................ 21 Contents 5.3.1 Farming.......................... 21 5.3.2 Ranching......................... 22 Executive Summary.................... 1 5.3.3 Oil and gas extraction........... 22 5.3.4 Tourism........................... 22 1. Introduction......................... 2 5.4 Conservation management achieved 1.1 Why protect birds...................... 2 at site................................... 22 5.4.1 Saskatchewan game preserves. 22 5.4.2 Conservation easements act.... 22 2 IBA Site Information................ 4 5.4.3 Piping Plover survey............ 23 5.4.4 Ducks Unlimited Canada....... 23 2.1 Existing large scale conservation 5.4.5 Monitoring....................... 24 measures............................... 5 2.1.1 Federal and provincial acts..... 5 2.1.2 The proposed Species-at-Risk 6 Opportunities........................ 24 Act................................. 6 2.1.3 Canadian Biodiversity 6.1 Water quality and quantity........... -

Annual Report

PROVINCE OF SASKATCHEWAN 10-11 ANNUAL REPORT MINISTRY OF TOURISM, PARKS, CULTURE AND SPORT Table of Contents Letters of Transmittal ............................................................................................................ 2 Minister .................................................................................................................................. 2 Deputy Minister...................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 4 Alignment with the Government’s Direction ....................................................................... 5 Ministry Overview .................................................................................................................. 6 Progress in 2010–11 .............................................................................................................. 8 Government Goal – Economic Growth Promote tourism development and investment ..................................................................... 8 Government Goal – Security Promote a vibrant and sustainable creative and cultural sector ........................................... 13 Promote healthy, active families and community vitality through sport, culture and recreation ................................................................................................ 16 Provide effective stewardship and development -

The International Programs Guide

the international programs guide A DIRECTORY OF OPPORTUNITIES AND RESSOURCES FOR TRAVELLERS ACCESS TO TRAVEL ATT is a governmental source of information to make travel easier and more enjoyable for Canadians with disabilities and seniors, as well as for their families and caregivers. ADVENTURE LIFE Adventure Life is an American travel agency offering over 80 ethical destinations and all kinds of experiences, from foodies trips to trekking to honeymoons. AEISEC AIESEC is an international non-governmental non-profit organization in consultative status with the United Nations Economic and Social Council fully ran by students offering volunteering and internship opportunities worldwide. AFS INTERCULTURE CANADA AFS is an international non-profit organization providing student exchange programs, hosting opportunities and volunteering programs for adults. ANIMAL EXPERIENCE INTERNATIONAL AEI is a Canadian non-profit empowering animal lovers, students, professionals and adventure seekers to travel and make a difference by volunteering with animals. ARTS ABROAD The Canadian Council for the arts supports the international outreach of Canadian artists by reimbursing travel expenses for exhibitions, training and touring. AUPAIRWORLD Au pair placement service to connect travellers aged between 18 and 30 to host families where they will live free of charge in exchange for a helping hand with childcare and housework. CANADA HOMESTAY NETWORK Since 1995, CHN, a family-run non-profit society, has helped tens of thousands of students find a home away from home in Canada. You can register to host an international student. CANADA KEEP EXPLORING Official website of Destination Canada, the Canadian tourism office. CANADA WORLD YOUTH CWY offers international volunteer programs to youth from Canada and abroad who, through their participation in community-driven development projects, acquire the leadership skills that allow them to become agents of change.