Quill Lakes Important Bird Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 31 S T Annual

THE 31ST ANNUAL NOVEMBER 10, 2020 NOVEMBER 10, 2020 MASTER OF CEREMONIES Mary Taylor-Ash CEO Tourism Saskatchewan PRESENTER Norm Beug Chair Tourism Saskatchewan Board of Directors 2 NOVEMBER 10, 2020 SASKATCHEWAN TOURISM AWARDS OF EXCELLENCE More than 30 years ago, Saskatchewan’s tourism sector began paying special tribute to leadership and achievement in the industry – to businesses and individuals who made exceptional contributions to tourism and demonstrated that success and fulfilment come with being true to your dreams, proud of your home and eager to treat guests to remarkable Saskatchewan experiences. The Saskatchewan Tourism Awards of Excellence Gala has become a yearly showcase of achievement, bringing together representatives from every corner of the province and from a diverse range of businesses and attractions to celebrate the accomplishments of their colleagues in the industry. Originally scheduled to take place on April 2 in Regina, the 31st annual event was cancelled, along with the HOST Saskatchewan Conference, due to the COVID-19 pandemic. With the cancellation of both industry gatherings, the announcement of the 12 Saskatchewan Tourism Awards of Excellence recipients and three Tourism Builders was postponed. Through the use of technology and adoption of a new virtual format, members of Saskatchewan’s tourism industry are now able to gather from afar to honour those outstanding businesses and people who have gone above and beyond to deliver superior service and experiences. Join the celebration as the Saskatchewan Tourism Awards of Excellence shine a spotlight on the commitment and hard work of veteran operators, as well as the innovative spirit of young entrepreneurs, and broaden understanding of efforts that yield success and, ultimately, position Saskatchewan as a more inviting and competitive destination. -

Going Places • Summer 2019 • 1

Going Places • Summer 2019 • 1 Summer 2019 2 6 11 18 SASKSECRETS SPORTS TOP FIVE TIPS FOR COMPLETING DESTINATION RECONCILIATION AND NEW LOOK AN AWARD NOMINATION DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY DIVERSITY ADDRESSED IN LAUNCHES FRAMEWORK WDM INCLUSIVITY REPORT TO ENRICH AND GROW TOURISM 2 • Going Places • Summer 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS Editor SaskSecrets sports new look ..............................................2 New funding pilot programs accepting applications Susan Parkin Message from the CEO .........................................................3 on October 1-November 15 .............................................11 Tourism Saskatchewan Tourism and jobs provide focus for World STEC News 189 - 1621 Albert Street Tourism Day ..............................................................................3 Tourism Workplace Leadership Conference Regina, Saskatchewan Saskatchewan increasingly attracts U.S. anglers focuses on tourism careers ...............................................12 Canada S4P 2S5 and hunters ..............................................................................4 Ashley Stone receives Tourism Phone: 306-787-2927 Message from the Chair .......................................................5 Ambassador Award .............................................................12 Fax: 306-787-6293 Tourism Saskatchewan releases 2018-2019 Introducing Amanda Ruller, I Heart Tourism Email: [email protected] Annual Report ..........................................................................5 influencer ................................................................................12 -

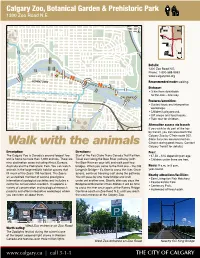

Calgary Zoo Commute

Calgary Zoo, Botanical Garden & Prehistoric Park 1300 Zoo Road N.E. ± NW NE TRANS CENTRE ST CANADA BO W HWY RI VER MEMORIAL DR TR MACLEOD SW SE 2" Details: 1300 Zoo Road N.E. ! ! ! Phone: 1-800-588-9993 ! ! ! 1 www.calgaryzoo.org ! .1 ! ! ! DOWNTOWN ! ! ! ! ! Recommended mode: walking. ! ! ! 1.3 ! ! ! 2" ! ! ! ! Distance: ! ! 2" 2" 2" 2" 2" • 3 km from downtown 2" 2" 2" ! 2" 2" 2" 2" to the Zoo – one way. CALGARY ZOO Features/amenities: • Guided tours and interpretive workshops. • Children’s playground. • Gift shops and food kiosks. 2" • Train tour for children. Alternative access via transit: If you wish to do part of the trip by transit, you can also reach the Calgary Zoo by CTrain route 202. (Note: bicycles are restricted on Walk with the animals CTrains during peak hours. Contact Calgary Transit for details.) Description: Directions: Fees: The Calgary Zoo is Canada’s second largest zoo Start at the Eau Claire Trans Canada Trail Pavilion. • $7.50 – $16 depending on age. and is home to more than 1,000 animals. There are Travel east along the Bow River pathway (with • Children under three are free. nine destination areas including Africa, Eurasia, the Bow River on your left) and walk past two Australia and the Prehistoric Park. You can watch bridges. When you come to the third one – the Old Hours: 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. animals in the large realistic habitat spaces that Langevin Bridge – it’s time to cross the river. Once year-round. fill much of the Zoo’s 159 hectares. -

Tourism Saskatchewan 2017-2018 Annual Report $2.37 Billion in Travel Expenditures

Tourism Saskatchewan 2017-2018 Annual Report $2.37 billion in travel expenditures 13.6 million visits to and within Saskatchewan 1.4 billion advertising and marketing-generated impressions 67,200 residents employed in tourism 4,200 Saskatchewan tourism products and services Cover image: Fort Walsh National Historic Site Vision: A vibrant entrepreneurial tourism industry offering year-round compelling and memorable Saskatchewan experiences mission: Connect people with quality Saskatchewan experiences and advance the development of successful tourism operations Night sky over Meacham 2 Tourism Saskatchewan 2017-2018 Annual Report Letter of Transmittal His Honour, The Honourable W. Thomas Molloy Lieutenant Governor of the Province of Saskatchewan May it Please Your Honour: With respect, I submit Tourism Saskatchewan’s Annual Report for the fiscal period ending March 31, 2018. In compliance with The Tourism Saskatchewan Act , this document outlines the corporation’s business activities and includes audited financial statements. Gene Makowsky Minister Responsible for Tourism Saskatchewan Introduction This annual report contains information about Government Direction for 2017-18: Meeting the Tourism Saskatchewan’s activities during the past Challenge, The Saskatchewan Plan for Growth fiscal year (April 1, 2017 to March 31, 2018), along – Vision 2020 and Beyond , throne speeches and with financial statements for that period. other statements. The purpose of the document is to report to public The information contained within demonstrates and elected -

PIPELINE FOODS, LLC, Et Al.,1 Debtors. Chapter 11 Case

Case 21-11002-KBO Doc 110 Filed 07/23/21 Page 1 of 54 IN THE UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF DELAWARE In re: Chapter 11 PIPELINE FOODS, LLC, et al.,1 Case No. 21-11002 (KBO) Debtors. Jointly Administered AFFIDAVIT OF SERVICE I, Sabrina G. Tu, depose and say that I am employed by Stretto, the claims and noticing agent for the Debtors in the above-captioned cases. On July 21, 2021, at my direction and under my supervision, employees of Stretto caused the following documents to be served via overnight mail on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit A, and via electronic mail on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit B: • Notice of Telephonic Section 341 Meeting (Docket No. 73) • Application of the Debtors for Entry of an Order Pursuant to Bankruptcy Code Section 327(a), Bankruptcy Rules 2014(a) and 2016, and Local Rules 2014-1 and 2016- 2, Authorizing Appointment of Bankruptcy Management Solutions, Inc. d/b/a Stretto as Administrative Agent to the Debtors, Effective as of the Petition Date (Docket No. 85) • Motion of the Debtors for the Entry of an Order Authorizing (I) Retention and Employment of SierraConstellation Partners, LLC to Provide Interim Management Services, a Chief Restructuring Officer, and Additional Personnel, and (II) the Designation of Winston Mar as Chief Restructuring Officer, Effective as of the Petition Date (Docket No. 86) • Debtors’ Motion for Entry of Order Authorizing Debtors to Retain and Compensate Professionals Utilized in the Ordinary Course of Business, Effective as of the Petition Date (Docket No. -

Saskatchewan Intraprovincial Miles

GREYHOUND CANADA PASSENGER FARE TARIFF AND SALES MANUAL GREYHOUND CANADA TRANSPORTATION ULC. SASKATCHEWAN INTRA-PROVINCIAL MILES The miles shown in Section 9 are to be used in connection with the Mileage Fare Tables in Section 6 of this Manual. If through miles between origin and destination are not published, miles will be constructed via the route traveled, using miles in Section 9. Section 9 is divided into 8 sections as follows: Section 9 Inter-Provincial Mileage Section 9ab Alberta Intra-Provincial Mileage Section 9bc British Columbia Intra-Provincial Mileage Section 9mb Manitoba Intra-Provincial Mileage Section9on Ontario Intra-Provincial Mileage Section 9pq Quebec Intra-Provincial Mileage Section 9sk Saskatchewan Intra-Provincial Mileage Section 9yt Yukon Territory Intra-Provincial Mileage NOTE: Always quote and sell the lowest applicable fare to the passenger. Please check Section 7 - PROMOTIONAL FARES and Section 8 – CITY SPECIFIC REDUCED FARES first, for any promotional or reduced fares in effect that might result in a lower fare for the passenger. If there are none, then determine the miles and apply miles to the appropriate fare table. Tuesday, July 02, 2013 Page 9sk.1 of 29 GREYHOUND CANADA PASSENGER FARE TARIFF AND SALES MANUAL GREYHOUND CANADA TRANSPORTATION ULC. SASKATCHEWAN INTRA-PROVINCIAL MILES City Prv Miles City Prv Miles City Prv Miles BETWEEN ABBEY SK AND BETWEEN ALIDA SK AND BETWEEN ANEROID SK AND LANCER SK 8 STORTHOAKS SK 10 EASTEND SK 82 SHACKLETON SK 8 BETWEEN ALLAN SK AND HAZENMORE SK 8 SWIFT CURRENT SK 62 BETHUNE -

Saskatchewan Regional Newcomer Gateways

Saskatchewan Regional Newcomer Gateways Updated September 2011 Meadow Lake Big River Candle Lake St. Walburg Spiritwood Prince Nipawin Lloydminster wo Albert Carrot River Lashburn Shellbrook Birch Hills Maidstone L Melfort Hudson Bay Blaine Lake Kinistino Cut Knife North Duck ef Lake Wakaw Tisdale Unity Battleford Rosthern Cudworth Naicam Macklin Macklin Wilkie Humboldt Kelvington BiggarB Asquith Saskatoonn Watson Wadena N LuselandL Delisle Preeceville Allan Lanigan Foam Lake Dundurn Wynyard Canora Watrous Kindersley Rosetown Outlook Davidson Alsask Ituna Yorkton Legend Elrose Southey Cupar Regional FortAppelle Qu’Appelle Melville Newcomer Lumsden Esterhazy Indian Head Gateways Swift oo Herbert Caronport a Current Grenfell Communities Pense Regina Served Gull Lake Moose Moosomin Milestone Kipling (not all listed) Gravelbourg Jaw Maple Creek Wawota Routes Ponteix Weyburn Shaunavon Assiniboia Radwille Carlyle Oxbow Coronachc Regway Estevan Southeast Regional College 255 Spruce Drive Estevan Estevan SK S4A 2V6 Phone: (306) 637-4920 Southeast Newcomer Services Fax: (306) 634-8060 Email: [email protected] Website: www.southeastnewcomer.com Alameda Gainsborough Minton Alida Gladmar North Portal Antler Glen Ewen North Weyburn Arcola Goodwater Oungre Beaubier Griffin Oxbow Bellegarde Halbrite Radville Benson Hazelwood Redvers Bienfait Heward Roche Percee Cannington Lake Kennedy Storthoaks Carievale Kenosee Lake Stoughton Carlyle Kipling Torquay Carnduff Kisbey Tribune Coalfields Lake Alma Trossachs Creelman Lampman Walpole Estevan -

Learning with Wetlands at the Sam Livingston Fish Hatchery: a Marriage of Mind and Nature

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies Legacy Theses 1999 Learning with wetlands at the Sam Livingston fish hatchery: A marriage of mind and nature Grieef, Patricia Lynn Grieef, P. L. (1999). Learning with wetlands at the Sam Livingston fish hatchery: A marriage of mind and nature (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/12963 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/25035 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca The University of Calgary Leurnhg with wetiads at the Sam Livingston Fish Hatchery: A Marriage of Mind and Nature by Patricia L. Grieef A Master's Degree Project submitted to the Faculty of Environmental Design in partial hlfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Environmental Design (Environmental Science) Calgary, Alberta September, 1999 O Patricia L. Grieef, 1999 National Library BibliotWque nationale 1*1 .,&"a& du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. nn, Wellington OttawaON KlAW OCtewaON K1AON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive pennettant a la National Library of Canada to Bibliotheque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, preter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. -

Bioadvantage Trials Program the Leading Pea 2 Tagteam Bioniq VS

2020 BIOADVANTAGE HARVEST TRIALS DATA inoculant on pea Results - pea Over the past 6 years, e orts from producers, retails, Table of contents and agronomists like you have contributed to making the BioAdvantage Trials program the leading Pea 2 TagTeam BioniQ VS. Competitors Average Yield inoculant fi eld scale testing program in the industry. TagTeam Yield Competitor Location Year BioniQ Di erence TagTeam BioniQ 2 (bu/ac) The successful development and testing of inoculant Yield (bu/ac) (bu/ac) All competitors products has contributed to a deeper understanding TagTeam LCO 3 Forestburg, AB 2019 48.0 46.0 2.0 49.3 (bu/ac) of the agronomics, placement, and expectations Innisfail, AB 2020 71.4 68.5 2.8 of the portfolio. Lentil 4 Magrath, AB 2019 34.2 35.0 -0.8 Peas TagTeam BioniQ Munson, AB 2018 29.3 27.3 2.0 52.8 (bu/ac) As a result of your commitment to the program, TagTeam BioniQ 4 Oyen, AB 2018 53.3 54.2 -0.9 over 400 trials – across 6 provinces, with Oyen, AB 2020 34.0 35.7 -1.7 TagTeam LCO 5 Cabri, SK 2019 52.6 48.7 3.9 6 di erent inoculants on 12 di erent crops Source: Results were collected from 26 farmer-conducted, large- have been completed. Canwood, SK 2018 55.1 43.2 11.9 scale, side-by-side BioAdvantage Trials conducted in Alberta and Saskatchewan from 2017-2020. Barley 6 Govan, SK 2018 42.2 41.0 1.2 Thank you for your continued support, and Govan, SK 2018 42.2 40.7 1.5 we look forward to collaborating on future BioniQ 6 Kinley, SK 2018 66.9 63.6 3.3 BioAdvantage Trials to test the inoculant Leross, SK 2019 58.8 49.6 9.2 Wheat 7 and micronutrient products from McLean, SK 2019 43.6 38.5 5.1 the expanded NexusBioAg portfolio. -

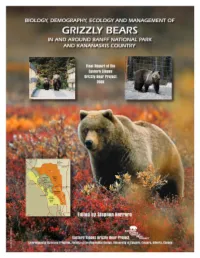

Final Report of the Eastern Slopes Grizzly Bear Project

Credits for cover photographs: Brian Wolitski Main cover photograph Anonymous Lake Louise visitor Grizzly bear family group on footbridge Cedar Mueller Bear #56 against fence Cover design Rob Storeshaw, Parks Canada, Calgary, Alberta Document design, layout and formatting: KH Communications, Canmore, Alberta Suggested means of citing this document Herrero, Stephen (editor). 2005. Biology, demography, ecology and management of grizzly bears in and around Banff National Park and Kananaskis Country: The final report of the Eastern Slopes Grizzly Bear Project. Faculty of Environmental Design, University of Calgary, Alberta, Canada. Suggested means of citing chapters or sections of this document S. Stevens, and M. Gibeau. 2005. Research methods regarding capture, handling and telemetry. Pages 17 — 19 in S. Herrero, editor. Biology, demography, ecology and management of grizzly bears in and around Banff National Park and Kananaskis Country: The final report of the Eastern Slopes Grizzly Bear Project. Faculty of Environmental Design, University of Calgary, Alberta, Canada. BIOLOGY, DEMOGRAPHY, ECOLOGY AND MANAGEMENT OF GRIZZLY BEARS IN AND AROUND BANFF NATIONAL PARK AND KANANASKIS COUNTRY Final Report of the Eastern Slopes Grizzly Bear Project 2005 Edited by Stephen Herrero Eastern Slopes Grizzly Bear Project, Environmental Sciences Program, Faculty of Environmental Design, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada. ii DEDICATION To everyone who cares about grizzly bears and wildlife and the ecological systems and processes that support them. To the graduate students who were the core researchers: Bryon Benn, Mike Gibeau, John Kansas, Cedar Mueller, Karen Oldershaw, Saundi Stevens, and Jen Theberge. To the funding supporters who had the vision and faith that our research would be worthwhile. -

Pearce Estate Park What We Heard #1

Design Development Plan Phase 2: Pearce Estate Park What We Heard #1: Vision & Programming March–April 2016 _ Report prepared: April 2016 Contents What is Bend in the Bow? 1 Engagement Overview 3 What We Asked 6 What We Heard 7 What We Heard + What We Will Do 12 Next Steps 20 Appendix: Verbatim Comments 21 What is Bend in the Bow? The City of Calgary has begun a long-term project to Phase 1 of this project is completed. It focused on the IBS connect the Inglewood Bird Sanctuary (IBS), Pearce Estate and the Inglewood Wildlands. Please go to Park and the adjoining green spaces along the Bow River— calgary.ca/bendinthebow for a review on what was this project is called Bend in the Bow. discussed and heard at the engagement sessions, and how the preferred design concept evolved. The goal of the project is to explore and address ways to preserve, enhance and celebrate the only urban-centred, Phase 2 of the project is now underway. Phase 2 focuses on federally-recognized bird sanctuary in Canada, while Pearce Estate Park and the adjoining green spaces along the retaining the historic significance of the other lands located Bow River towards the Inglewood Bird Sanctuary. within the new area boundaries. The Design Development Plan (DDP) will integrate the various areas of the two phases Building on Phase 1, Phase 2 will continue with the vision into one cohesive and well-functioning landscape unit. of “a park that tells stories,” with a focus on balancing the core values of nature, culture and education. -

A Guide to Community Tourism Planning in Nova Scotia

A Guide to Community Tourism Planning in Nova Scotia Prepared by: THE ECONOMIC PLANNING GROUP of Canada Halifax, Nova Scotia COPYRIGHT ©2005 by Her Majesty the Queen in right of the Province of Nova Scotia All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without the prior written consent of The Province of Nova Scotia. The publisher is not engaged in rendering legal, accounting or other professional advice. If legal advice or expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought. The information and analysis contained herein is intended to be general and represents the research of the authors and should in no way be construed as being definitive or as being official or unofficial policy of any government body. Any reliance on the Guide shall be at the reader’s own risk. Table of Contents SECTION 1: INTRODUCTION ..................................................... 1 1.1 Purpose of the Guide ........................................................... 1 1.2 Contents of the Manual.......................................................... 2 1.3 Why Should your Community have a Tourism Plan? .................................. 3 SECTION 2: THE TOURISM INDUSTRY ............................................ 5 2.1 What is Tourism?.............................................................. 5 2.2 The International and National Context............................................. 6 International Travel and Tourism .......................................... 6 Tourism in Canada.....................................................