University Microfilms International 300 N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The University of Chicago Tears in the Imperial Screen

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO TEARS IN THE IMPERIAL SCREEN: WARTIME COLONIAL KOREAN CINEMA, 1936-1945 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF EAST ASIAN LANGUAGES AND CIVILIZATIONS BY HYUN HEE PARK CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES ...…………………..………………………………...……… iii LIST OF FIGURES ...…………………………………………………..……….. iv ABSTRACT ...………………………….………………………………………. vi CHAPTER 1 ………………………..…..……………………………………..… 1 INTRODUCTION CHAPTER 2 ……………………………..…………………….……………..… 36 ENLIGHTENMENT AND DISENCHANTMENT: THE NEW WOMAN, COLONIAL POLICE, AND THE RISE OF NEW CITIZENSHIP IN SWEET DREAM (1936) CHAPTER 3 ……………………………...…………………………………..… 89 REJECTED SINCERITY: THE FALSE LOGIC OF BECOMING IMPERIAL CITIZENS IN THE VOLUNTEER FILMS CHAPTER 4 ………………………………………………………………… 137 ORPHANS AS METAPHOR: COLONIAL REALISM IN CH’OE IN-GYU’S CHILDREN TRILOGY CHAPTER 5 …………………………………………….…………………… 192 THE PLEASURE OF TEARS: CHOSŎN STRAIT (1943), WOMAN’S FILM, AND WARTIME SPECTATORSHIP CHAPTER 6 …………………………………………….…………………… 241 CONCLUSION BIBLIOGRAPHY …………………………………………………………….. 253 FILMOGRAPHY OF EXTANT COLONIAL KOREAN FILMS …………... 265 ii LIST OF TABLES Page Table 1. Newspaper articles regarding traffic film screening events ………....…54 Table 2. Newspaper articles regarding traffic film production ……………..….. 56 iii LIST OF FIGURES Page Figure. 1-1. DVDs of “The Past Unearthed” series ...……………..………..…..... 3 Figure. 1-2. News articles on “hygiene film screening” in Maeil sinbo ….…... 27 Figure. 2-1. An advertisement for Sweet Dream in Maeil sinbo……………… 42 Figure. 2-2. Stills from Sweet Dream ………………………………………… 59 Figure. 2-3. Stills from the beginning part of Sweet Dream ………………….…65 Figure. 2-4. Change of Ae-sun in Sweet Dream ……………………………… 76 Figure. 3-1. An advertisement of Volunteer ………………………………….. 99 Figure. 3-2. Stills from Volunteer …………………………………...……… 108 Figure. -

Yun Mi Hwang Phd Thesis

SOUTH KOREAN HISTORICAL DRAMA: GENDER, NATION AND THE HERITAGE INDUSTRY Yun Mi Hwang A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2011 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/1924 This item is protected by original copyright This item is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence SOUTH KOREAN HISTORICAL DRAMA: GENDER, NATION AND THE HERITAGE INDUSTRY YUN MI HWANG Thesis Submitted to the University of St Andrews for the Degree of PhD in Film Studies 2011 DECLARATIONS I, Yun Mi Hwang, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 80,000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student and as a candidate for the degree of PhD in September 2006; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2006 and 2010. I, Yun Mi Hwang, received assistance in the writing of this thesis in respect of language and grammar, which was provided by R.A.M Wright. Date …17 May 2011.… signature of candidate ……………… I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of PhD in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

March 2018 New Releases

March 2018 New Releases what’s inside featured exclusives PAGE 3 RUSH Releases Vinyl Available Immediately! 59 Vinyl Audio 3 CD Audio 8 RICHIE KOTZEN - TONY MACALPINE - RANDY BRECKER QUINTET - FEATURED RELEASES TELECASTERS & DEATH OF ROSES LIVEAT SWEET BASIL 1988 STRATOCASTERS: Music Video KLASSIC KOTZEN DVD & Blu-ray 35 Non-Music Video DVD & Blu-ray 39 Order Form 65 Deletions and Price Changes 63 800.888.0486 THE SOULTANGLER KILLER KLOWNS FROM BRUCE’S DEADLY OUTER SPACE FINGERS 203 Windsor Rd., Pottstown, PA 19464 [BLU-RAY + DVD] DWARVES & THE SLOTHS - DUNCAN REID & THE BIG HEADS - FREEDOM HAWK - www.MVDb2b.com DWARVES MEET THE SLOTHS C’MON JOSEPHINE BEAST REMAINS SPLIT 7 INCH March Into Madness! MVD offers up a crazy batch of March releases, beginning with KILLER KLOWNS FROM OUTER SPACE! An alien invasion with a circus tent for a spaceship and Killer Klowns for inhabitants! These homicidal clowns are no laughing matter! Arrow Video’s exclusive deluxe treatment comes with loads of extras and a 4K restoration that will provide enough eye and ear candy to drive you insane! The derangement continues with HELL’S KITTY, starring a possessed cat who cramps the style of its owner, who is beginning a romantic relationship. Call a cat exorcist, because this fiery feline will do anything from letting its master get some pu---! THE BUTCHERING finds a serial killer returning to a small town for unfinished business. What a cut-up! The King of Creepy, CHRISTOPHER LEE, stars in the 1960 film CITY OF THE DEAD, given new life with the remastered treatment. -

D2492609215cd311123628ab69

Acknowledgements Publisher AN Cheongsook, Chairperson of KOFIC 206-46, Cheongnyangni-dong, Dongdaemun-gu. Seoul, Korea (130-010) Editor in Chief Daniel D. H. PARK, Director of International Promotion Department Editors KIM YeonSoo, Hyun-chang JUNG English Translators KIM YeonSoo, Darcy PAQUET Collaborators HUH Kyoung, KANG Byeong-woon, Darcy PAQUET Contributing Writer MOON Seok Cover and Book Design Design KongKam Film image and still photographs are provided by directors, producers, production & sales companies, JIFF (Jeonju International Film Festival), GIFF (Gwangju International Film Festival) and KIFV (The Association of Korean Independent Film & Video). Korean Film Council (KOFIC), December 2005 Korean Cinema 2005 Contents Foreword 04 A Review of Korean Cinema in 2005 06 Korean Film Council 12 Feature Films 20 Fiction 22 Animation 218 Documentary 224 Feature / Middle Length 226 Short 248 Short Films 258 Fiction 260 Animation 320 Films in Production 356 Appendix 386 Statistics 388 Index of 2005 Films 402 Addresses 412 Foreword The year 2005 saw the continued solid and sound prosperity of Korean films, both in terms of the domestic and international arenas, as well as industrial and artistic aspects. As of November, the market share for Korean films in the domestic market stood at 55 percent, which indicates that the yearly market share of Korean films will be over 50 percent for the third year in a row. In the international arena as well, Korean films were invited to major international film festivals including Cannes, Berlin, Venice, Locarno, and San Sebastian and received a warm reception from critics and audiences. It is often said that the current prosperity of Korean cinema is due to the strong commitment and policies introduced by the KIM Dae-joong government in 1999 to promote Korean films. -

Conference Reports – June 2012

Scope: An Online Journal of Film and Television Studies Issue 23 June 2012 Conference Reports – June 2012 Table of Contents East Winds: East Asian Cinema and Cultural Crossovers Symposium A report by Pierce Conran ...................................................................... 2 SCMS 2012: Society for Cinema and Media Studies Conference A report by Joan Dagle .......................................................................... 6 Contemporary Psychoanalysis, Literature and Film Symposium A report by Joanna Kellond .................................................................. 11 Monsters: Subject, Object, Abject A report by Ian Pettigrew .................................................................... 16 1 Conference Reports East Winds: East Asian Cinema and Cultural Crossovers Symposium Coventry University, Coventry, 2–3 March 2012 A report by Pierce Conran, Modern Korean Cinema (modernkoreancinema.com), Seoul, South Korea The “East Winds: East Asian Cinema and Cultural Crossovers Symposium”, held at Coventry University and organized by Spencer Murphy and Collette Balmain (both based at the host institution, which also funded the event), sought to reflect the diversity of East Asian cinema through a variety of different perspectives. In the current globalised world of cinema, international cross-pollination has become increasingly commonplace. Asian cinema, in the last fifteen years or so, has seen an explosion in co-productions as previously contentious diplomatic relationships across the continent have thawed. The -

Helsinki in Early Twentieth-Century Literature Urban Experiences in Finnish Prose Fiction 1890–1940

lieven ameel Helsinki in Early Twentieth-Century Literature Urban Experiences in Finnish Prose Fiction 1890–1940 Studia Fennica Litteraria The Finnish Literature Society (SKS) was founded in 1831 and has, from the very beginning, engaged in publishing operations. It nowadays publishes literature in the fields of ethnology and folkloristics, linguistics, literary research and cultural history. The first volume of the Studia Fennica series appeared in 1933. Since 1992, the series has been divided into three thematic subseries: Ethnologica, Folkloristica and Linguistica. Two additional subseries were formed in 2002, Historica and Litteraria. The subseries Anthropologica was formed in 2007. In addition to its publishing activities, the Finnish Literature Society maintains research activities and infrastructures, an archive containing folklore and literary collections, a research library and promotes Finnish literature abroad. Studia fennica editorial board Pasi Ihalainen, Professor, University of Jyväskylä, Finland Timo Kaartinen, Title of Docent, Lecturer, University of Helsinki, Finland Taru Nordlund, Title of Docent, Lecturer, University of Helsinki, Finland Riikka Rossi, Title of Docent, Researcher, University of Helsinki, Finland Katriina Siivonen, Substitute Professor, University of Helsinki, Finland Lotte Tarkka, Professor, University of Helsinki, Finland Tuomas M. S. Lehtonen, Secretary General, Dr. Phil., Finnish Literature Society, Finland Tero Norkola, Publishing Director, Finnish Literature Society Maija Hakala, Secretary of the Board, Finnish Literature Society, Finland Editorial Office SKS P.O. Box 259 FI-00171 Helsinki www.finlit.fi Lieven Ameel Helsinki in Early Twentieth- Century Literature Urban Experiences in Finnish Prose Fiction 1890–1940 Finnish Literature Society · SKS · Helsinki Studia Fennica Litteraria 8 The publication has undergone a peer review. The open access publication of this volume has received part funding via a Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation grant. -

Vision, Desire and Economies of Transgression in the Films of Jess Franco

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 1 Journeys into Perversion: Vision, Desire and Economies of Transgression in the Films of Jess Franco Glenn Ward Doctor of Philosophy University of Sussex May 2011 2 I hereby declare that this thesis has not been, and will not be, submitted whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Signature:……………………………………… 3 Summary Due to their characteristic themes (such as „perverse‟ desire and monstrosity) and form (incoherence and excess), exploitation films are often celebrated as inherently subversive or transgressive. I critically assess such claims through a close reading of the films of the Spanish „sex and horror‟ specialist Jess Franco. My textual and contextual analysis shows that Franco‟s films are shaped by inter-relationships between authorship, international genre codes and the economic and ideological conditions of exploitation cinema. Within these conditions, Franco‟s treatment of „aberrant‟ and gothic desiring subjectivities appears contradictory. Contestation and critique can, for example, be found in Franco‟s portrayal of emasculated male characters, and his female vampires may offer opportunities for resistant appropriation. -

Copyright by Leah Michelle Ross 2012

Copyright by Leah Michelle Ross 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Leah Michelle Ross Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: A Rhetoric of Instrumentality: Documentary Film in the Landscape of Public Memory Committee: Katherine Arens, Supervisor Barry Brummett, Co-Supervisor Richard Cherwitz Dana Cloud Andrew Garrison A Rhetoric of Instrumentality: Documentary Film in the Landscape of Public Memory by Leah Michelle Ross, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December, 2012 Dedication For Chaim Silberstrom, who taught me to choose life. Acknowledgements This dissertation was conceived with insurmountable help from Dr. Katherine Arens, who has been my champion in both my academic work as well as in my personal growth and development for the last ten years. This kind of support and mentorship is rare and I can only hope to embody the same generosity when I am in the position to do so. I am forever indebted. Also to William Russell Hart, who taught me about strength in the process of recovery. I would also like to thank my dissertation committee members: Dr Barry Brummett for his patience through the years and maintaining a discipline of cool; Dr Dana Cloud for her inspiring and invaluable and tireless work on social justice issues, as well as her invaluable academic support in the early years of my graduate studies; Dr. Rick Cherwitz whose mentorship program provides practical skills and support to otherwise marginalized students is an invaluable contribution to the life of our university and world as a whole; Andrew Garrison for teaching me the craft I continue to practice and continuing to support me when I reach out with questions of my professional and creative goals; an inspiration in his ability to juggle filmmaking, teaching, and family and continued dedication to community based filmmaking programs. -

K O R E a N C in E M a 2 0

KOREAN CINEMA 2006 www.kofic.or.kr/english Korean Cinema 2006 Contents FOREWORD 04 KOREAN FILMS IN 2006 AND 2007 05 Acknowledgements KOREAN FILM COUNCIL 12 PUBLISHER FEATURE FILMS AN Cheong-sook Fiction 22 Chairperson Korean Film Council Documentary 294 206-46, Cheongnyangni-dong, Dongdaemun-gu, Seoul, Korea 130-010 Animation 336 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Daniel D. H. PARK Director of International Promotion SHORT FILMS Fiction 344 EDITORS Documentary 431 JUNG Hyun-chang, YANG You-jeong Animation 436 COLLABORATORS Darcy Paquet, Earl Jackson, KANG Byung-woon FILMS IN PRODUCTION CONTRIBUTING WRITER Fiction 470 LEE Jong-do Film image, stills and part of film information are provided by directors, producers, production & sales companies, and Film Festivals in Korea including JIFF (Jeonju International Film Festival), PIFF APPENDIX (Pusan International Film Festival), SIFF (Seoul Independent Film Festival), Women’s Film Festival Statistics 494 in Seoul, Puchon International Fantastic Film Festival, Seoul International Youth Film Festival, Index of 2006 films 502 Asiana International Short Film Festival, and Experimental Film and Video Festival in Seoul. KOFIC appreciates their help and cooperation. Contacts 517 © Korean Film Council 2006 Foreword For the Korean film industry, the year 2006 began with LEE Joon-ik's <King and the Clown> - The Korean Film Council is striving to secure the continuous growth of Korean cinema and to released at the end of 2005 - and expanded with BONG Joon-ho's <The Host> in July. First, <King provide steadfast support to Korean filmmakers. This year, new projects of note include new and the Clown> broke the all-time box office record set by <Taegukgi> in 2004, attracting a record international support programs such as the ‘Filmmakers Development Lab’ and the ‘Business R&D breaking 12 million viewers at the box office over a three month run. -

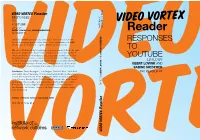

Reader R E a D

Reader RESPONSES TO YOUTUBE EDITED BY GEERT LOVINK AND SABINE NIEDERER INC READER #4 R E The Video Vortex Reader is the first collection of critical texts to deal with R the rapidly emerging world of online video – from its explosive rise in 2005 with YouTube, to its future as a significant form of personal media. After years of talk about digital convergence and crossmedia platforms we now witness the merger of the Internet and television at a pace no-one predicted. These contributions from scholars, artists and curators evolved from the first SABINE NIEDE two Video Vortex conferences in Brussels and Amsterdam in 2007 which fo- AND cused on responses to YouTube, and address key issues around independent production and distribution of online video content. What does this new dis- tribution platform mean for artists and activists? What are the alternatives? T LOVINK Contributors: Tilman Baumgärtel, Jean Burgess, Dominick Chen, Sarah Cook, R Sean Cubitt, Stefaan Decostere, Thomas Elsaesser, David Garcia, Alexandra GEE Juhasz, Nelli Kambouri and Pavlos Hatzopoulos, Minke Kampman, Seth Keen, Sarah Késenne, Marsha Kinder, Patricia Lange, Elizabeth Losh, Geert Lovink, Andrew Lowenthal, Lev Manovich, Adrian Miles, Matthew Mitchem, Sabine DITED BY Niederer, Ana Peraica, Birgit Richard, Keith Sanborn, Florian Schneider, E Tom Sherman, Jan Simons, Thomas Thiel, Vera Tollmann, Andreas Treske, Peter Westenberg. Institute of Network Cultures, Amsterdam 2008 ISBN 978-90-78146-05-6 Reader 2 Reader RESPONSES TO YOUTUBE 3 Video Vortex Reader: Responses to YouTube Editors: Geert Lovink and Sabine Niederer Editorial Assistance: Marije van Eck and Margreet Riphagen Copy Editing: Darshana Jayemanne Design: Katja van Stiphout Cover image: Orpheu de Jong and Marco Sterk, Newsgroup Printer: Veenman Drukkers, Rotterdam Publisher: Institute of Network Cultures, Amsterdam 2008 Supported by: XS4ALL Nederland and the University of Applied Sciences, School of Design and Communication. -

![Inmedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online Since 22 April 2013, Connection on 22 September 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3954/inmedia-3-2013-%C2%AB-cinema-and-marketing-%C2%BB-online-online-since-22-april-2013-connection-on-22-september-2020-603954.webp)

Inmedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online Since 22 April 2013, Connection on 22 September 2020

InMedia The French Journal of Media Studies 3 | 2013 Cinema and Marketing Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/524 DOI: 10.4000/inmedia.524 ISSN: 2259-4728 Publisher Center for Research on the English-Speaking World (CREW) Electronic reference InMedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online since 22 April 2013, connection on 22 September 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/524 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ inmedia.524 This text was automatically generated on 22 September 2020. © InMedia 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Cinema and Marketing When Cultural Demands Meet Industrial Practices Cinema and Marketing: When Cultural Demands Meet Industrial Practices Nathalie Dupont and Joël Augros Jerry Pickman: “The Picture Worked.” Reminiscences of a Hollywood publicist Sheldon Hall “To prevent the present heat from dissipating”: Stanley Kubrick and the Marketing of Dr. Strangelove (1964) Peter Krämer Targeting American Women: Movie Marketing, Genre History, and the Hollywood Women- in-Danger Film Richard Nowell Marketing Films to the American Conservative Christians: The Case of The Chronicles of Narnia Nathalie Dupont “Paris . As You’ve Never Seen It Before!!!”: The Promotion of Hollywood Foreign Productions in the Postwar Era Daniel Steinhart The Multiple Facets of Enter the Dragon (Robert Clouse, 1973) Pierre-François Peirano Woody Allen’s French Marketing: Everyone Says Je l’aime, Or Do They? Frédérique Brisset Varia Images of the Protestants in Northern Ireland: A Cinematic Deficit or an Exclusive -

Track Title 1 Tamerlane 2 Song 3 Dreams 4 Spirits Of

Track Title 1 Tamerlane 2 Song 3 Dreams 4 Spirits of the Dead 5 Evening Star 6 A Dream 7 The Lake To 8 Alone 9 Sonnet - To Science 10 Al Aaraaf 11 To - "The bowers whereat..." 12 To the River … 13 To - "I heed not that my..." 14 Fairyland 15 To Helen 16 Israfel 17 The Sleeper 18 The Valley of Unrest 19 The City and the Sea 20 A Paean 21 Romance 22 Loss of Breath 23 Bon-Bon 24 The Duc De L'Omelette 25 Metzengerstein 26 A Tale of Jerusalem 27 To One in Paradise 28 The Assignation 29 Silence - A Fable 30 MS. Found in a Bottle 31 Four Beasts in One 32 Bérénice 33 King Pest 34 The Coliseum 35 To F--s. S. O--d 36 Hymn 37 Morella 38 Unparallelled Adventure of One Hans Pfall 39 Unparallelled Adventure of One Hans Pfall (continued) 40 Lionizing 41 Shadow - A Parable 42 Bridal Ballad 43 To Zante 44 Maelzel's Chess Player 45 Magazine Writing - Peter Snook 46 Narritive of A. Gordon Pym 47 Narritive of A. Gordon Pym (continued) 48 Narritive of A. Gordon Pym (continued) 49 Narritive of A. Gordon Pym (continued) 50 Narritive of A. Gordon Pym (continued) 51 Mystification 52 Ligeia 53 How to Write a Blackwood Article 54 A Predicament 55 Why the Little Frechman Wears His Hand in a Sling 56 The Haunted Palace 57 Silence 58 The Devil in the Belfry 59 William Wilson 60 The Man that was Used Up 61 The Fall of the House of Usher 62 The Business Man 63 The Man of the Crowd 64 The Murders of the Rue Morgue 65 The Murders of the Rue Morgue (continued) 66 Eleonora 67 A Descent into the Maelstrom 68 The Island of the Fay 69 Never Bet the Devil Your Head 70 Three Sundays in a Week 71 The Conqueror Worm 72 Lenore 73 The Oval Portrait 74 The Masque of the Red Death 75 The Pit and the Pendulum 76 The Mystery of Marie Roget 77 The Mystery of Marie Roget (continued) 78 The Domain of Arnheim 79 The Gold-Bug 80 The Gold-Bug (continued) 81 The Tell-Tale Heart 82 The Black Cat 83 Raising the Wind (a.k.a.