Immobilization of Heavy Metals in Contaminated Soils—Performance Assessment in Conditions Similar to a Real Scenario

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Periodic Electronegativity Table

The Periodic Electronegativity Table Jan C. A. Boeyens Unit for Advanced Study, University of Pretoria, South Africa Reprint requests to J. C. A. Boeyens. E-mail: [email protected] Z. Naturforsch. 2008, 63b, 199 – 209; received October 16, 2007 The origins and development of the electronegativity concept as an empirical construct are briefly examined, emphasizing the confusion that exists over the appropriate units in which to express this quantity. It is shown how to relate the most reliable of the empirical scales to the theoretical definition of electronegativity in terms of the quantum potential and ionization radius of the atomic valence state. The theory reflects not only the periodicity of the empirical scales, but also accounts for the related thermochemical data and serves as a basis for the calculation of interatomic interaction within molecules. The intuitive theory that relates electronegativity to the average of ionization energy and electron affinity is elucidated for the first time and used to estimate the electron affinities of those elements for which no experimental measurement is possible. Key words: Valence State, Quantum Potential, Ionization Radius Introduction electronegative elements used to be distinguished tra- ditionally [1]. Electronegativity, apart from being the most useful This theoretical notion, in one form or the other, has theoretical concept that guides the practising chemist, survived into the present, where, as will be shown, it is also the most bothersome to quantify from first prin- provides a precise definition of electronegativity. Elec- ciples. In historical context the concept developed in a tronegativity scales that fail to reflect the periodicity of natural way from the early distinction between antag- the L-M curve will be considered inappropriate. -

Removal of Heavy Metals from Aqueous Solution by Zeolite in Competitive Sorption System

International Journal of Environmental Science and Development, Vol. 3, No. 4, August 2012 Removal of Heavy Metals from Aqueous Solution by Zeolite in Competitive Sorption System Sabry M. Shaheen, Aly S. Derbalah, and Farahat S. Moghanm rich volcanic rocks (tuff) with fresh water in playa lakes or Abstract—In this study, the sorption behaviour of natural by seawater [5]. (clinoptilolite) zeolites with respect to cadmium (Cd), copper The structures of zeolites consist of three-dimensional (Cu), nickel (Ni), lead (Pb) and zinc (Zn) has been studied in frameworks of SiO and AlO tetrahedra. The aluminum ion order to consider its application to purity metal finishing 4 4 wastewaters. The batch method has been employed, using is small enough to occupy the position in the center of the competitive sorption system with metal concentrations in tetrahedron of four oxygen atoms, and the isomorphous 4+ 3+ solution ranging from 50 to 300 mg/l. The percentage sorption replacement of Si by Al produces a negative charge in and distribution coefficients (Kd) were determined for the the lattice. The net negative charge is balanced by the sorption system as a function of metal concentration. In exchangeable cation (sodium, potassium, or calcium). These addition lability of the sorbed metals was estimated by DTPA cations are exchangeable with certain cations in solutions extraction following their sorption. The results showed that Freundlich model described satisfactorily sorption of all such as lead, cadmium, zinc, and manganese [6]. The fact metals. Zeolite sorbed around 32, 75, 28, 99, and 59 % of the that zeolite exchangeable ions are relatively innocuous added Cd, Cu, Ni, Pb and Zn metal concentrations (sodium, calcium, and potassium ions) makes them respectively. -

Most Atoms Form Chemical Bonds to Obtain a Lower Potential Energy

Integrated Chemistry <Kovscek> 6-1-2 Explain why most atoms form chemical bonds. Most atoms form chemical bonds to obtain a lower potential energy. Many share or transfer electrons to get a noble gas configuration. 6-1-3 Describe ionic and covalent bonding. Ions form to lower the reactivity of an atom. Ionic bonding is when the attraction between many cations and anions hold atoms together. Covalent bonding results from the sharing of electron pairs between two atoms. That is, when atoms share electrons, the mutual attraction between the electrons (electron clouds) and protons (the nucleus) hold the atoms together. 6-1-4 Explain why most chemical bonding is neither purely ionic nor purely covalent. In order for a bond to be totally ionic one atom would have to have an electronegativity of zero. (there aren’t any). To have a purely covalent bond the electronegativity must be equal. (Only the electronegativity of atoms of the same element are identical, diatomic elements are purely covalent) 6-1-5 Classify bonding type according to electronegativity differences. Differences in electronegativities reflect the character of bonding between elements. The electronegativity of the less- electronegative element is subtracted from that of the more- electronegative element. The greater the electronegativity difference, the more ionic is the bonding. Covalent Bonding happens between atoms with an electronegativity difference of 1.7 or less. That is the bond has an ionic character of 50% or less. Electronegativity % Ionic Character Covalent Differences Bond Type 0 to 0.3 0% to 5% Non - Polar Over 0.3 up to 1.7 5% to 50% Polar Over 1.7 Greater than 50 % Ionic Ionic Bonding occurs between atoms with an electronegativity difference of greater than 1.7. -

ELECTRONEGATIVITY D Qkq F=

ELECTRONEGATIVITY The electronegativity of an atom is the attracting power that the nucleus has for it’s own outer electrons and those of it’s neighbours i.e. how badly it wants electrons. An atom’s electronegativity is determined by Coulomb’s Law, which states, “ the size of the force is proportional to the size of the charges and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them”. In symbols it is represented as: kq q F = 1 2 d 2 where: F = force (N) k = constant (dependent on the medium through which the force is acting) e.g. air q1 = charge on an electron (C) q2 = core charge (C) = no. of protons an outer electron sees = no. of protons – no. of inner shell electrons = main Group Number d = distance of electron from the nucleus (m) Examples of how to calculate the core charge: Sodium – Atomic number 11 Electron configuration 2.8.1 Core charge = 11 (no. of p+s) – 10 (no. of inner e-s) +1 (Group i) Chlorine – Atomic number 17 Electron configuration 2.8.7 Core charge = 17 (no. of p+s) – 10 (no. of inner e-s) +7 (Group vii) J:\Sciclunm\Resources\Year 11 Chemistry\Semester1\Notes\Atoms & The Periodic Table\Electronegativity.doc Neon holds onto its own electrons with a core charge of +8, but it can’t hold any more electrons in that shell. If it was to form bonds, the electron must go into the next shell where the core charge is zero. Group viii elements do not form any compounds under normal conditions and are therefore given no electronegativity values. -

Periodic Table 1 Periodic Table

Periodic table 1 Periodic table This article is about the table used in chemistry. For other uses, see Periodic table (disambiguation). The periodic table is a tabular arrangement of the chemical elements, organized on the basis of their atomic numbers (numbers of protons in the nucleus), electron configurations , and recurring chemical properties. Elements are presented in order of increasing atomic number, which is typically listed with the chemical symbol in each box. The standard form of the table consists of a grid of elements laid out in 18 columns and 7 Standard 18-column form of the periodic table. For the color legend, see section Layout, rows, with a double row of elements under the larger table. below that. The table can also be deconstructed into four rectangular blocks: the s-block to the left, the p-block to the right, the d-block in the middle, and the f-block below that. The rows of the table are called periods; the columns are called groups, with some of these having names such as halogens or noble gases. Since, by definition, a periodic table incorporates recurring trends, any such table can be used to derive relationships between the properties of the elements and predict the properties of new, yet to be discovered or synthesized, elements. As a result, a periodic table—whether in the standard form or some other variant—provides a useful framework for analyzing chemical behavior, and such tables are widely used in chemistry and other sciences. Although precursors exist, Dmitri Mendeleev is generally credited with the publication, in 1869, of the first widely recognized periodic table. -

Mendeleev's Periodic Table of the Elements the Periodic Table Is Thus

An Introduction to General / Inorganic Chemistry Mendeleev’s Periodic Table of the Elements Dmitri Mendeleev born 1834 in the Soviet Union. In 1869 he organised the 63 known elements into a periodic table based on atomic masses. He predicted the existence and properties of unknown elements and pointed out accepted atomic weights that were in error. The periodic table is thus an arrangement of the elements in order of increasing atomic number. Elements are arranged in rows called periods. Elements with similar properties are placed in the same column. These columns are called groups. An Introduction to General / Inorganic Chemistry The modern day periodic table can be further divided into blocks. http://www.chemsoc.org/viselements/pages/periodic_table.html The s, p, d and f blocks This course only deals with the s and p blocks. The s block is concerned only with the filling of s orbitals and contains groups I and II which have recently been named 1 and 2. The p block is concerned only with the filling of p orbitals and contains groups III to VIII which have recently been named 13 to 18. An Introduction to General / Inorganic Chemistry Groups exist because the electronic configurations of the elements within each group are the same. Group Valence Electronic configuration 1 s1 2 s2 13 s2p1 14 s2p2 15 s2p3 16 s2p4 17 s2p5 18 s2p6 The type of chemistry exhibited by an element is reliant on the number of valence electrons, thus the chemistry displayed by elements within a given group is similar. Physical properties Elemental physical properties can also be related to electronic configuration as illustrated in the following four examples: An Introduction to General / Inorganic Chemistry 1. -

Recent Developments in Chalcogen Chemistry

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN CHALCOGEN CHEMISTRY Tristram Chivers Department of Chemistry, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada WHERE IS CALGARY? Lecture 1: Background / Introduction Outline • Chalcogens (O, S, Se, Te, Po) • Elemental Forms: Allotropes • Uses • Trends in Atomic Properties • Spin-active Nuclei; NMR Spectra • Halides as Reagents • Cation Formation and Stabilisation • Anions: Structures • Solutions of Chalcogens in Ionic Liquids • Oxides and Imides: Multiple Bonding 3 Elemental Forms: Sulfur Allotropes Sulfur S6 S7 S8 S10 S12 S20 4 Elemental Forms: Selenium and Tellurium Allotropes Selenium • Grey form - thermodynamically stable: helical structure cf. plastic sulfur. R. Keller, et al., Phys. Rev. B. 1977, 4404. • Red form - cyclic Cyclo-Se8 (cyclo-Se7 and -Se6 also known). Tellurium • Silvery-white, metallic lustre; helical structure, cf. grey Se. • Cyclic allotropes only known entrapped in solid-state structures e.g. Ru(Ten)Cl3 (n = 6, 8, 9) M. Ruck, Chem. Eur. J. 2011, 17, 6382 5 Uses – Sulfur Sulfur : Occurs naturally in underground deposits. • Recovered by Frasch process (superheated water). • H2S in sour gas (> 70%): Recovered by Klaus process: Klaus Process: 2 H S + SO 3/8 S + 2 H O 2 2 8 2 • Primary industrial use (70 %): H2SO4 in phosphate fertilizers 6 Uses – Selenium and Tellurium Selenium and Tellurium : Recovered during the refining of copper sulfide ores Selenium: • Photoreceptive properties – used in photocopiers (As2Se3) • Imparts red color in glasses Tellurium: • As an alloy with Cu, Fe, Pb and to harden -

Periodic Table Trends Periodic Trends

Periodic Table Trends Periodic Trends • Atomic Radius • Ionization Energy • Electron Affinity The Trends in Picture Atomic Radius • Unlike a ball, an atom has fuzzy edges. • The radius of an atom can only be found by measuring the distance between the nuclei of two touching atoms, and then dividing that distance by two. Atomic Radius • Atomic radius is determined by how much the electrons are attracted to the positive nucleus. • The fewer the electrons in each period, the lesser the attraction. • Lesser attraction = • larger nucleus Atomic Radius Trend • Period: in general, as we go across a period from left to right, the atomic radius decreases – Effective nuclear charge increases, therefore the valence electrons are drawn closer to the nucleus, decreasing the size of the atom • Family: in general, as we down a group from top to bottom, the atomic radius increases – Orbital sizes increase in successive principal quantum levels Concept Check • Which should be the larger atom? Why? • O or N N • K or Ca K • Cl or F Cl • Be or Na Na • Li or Mg Mg Ionization Energy • Energy required to remove an electron from an atom • Which atom would be harder to remove an electron from? • Na Cl Ionization Energy • X + energy → X+ + e– X(g) → X+ (g) + e– • First electron removed is IE1 • Can remove more than one electron (IE2 , IE3 ,…) Ex. Magnesium Mg → Mg+ + e– IE1 = 735 kJ/mol Mg+ → Mg2+ + e– IE2 = 1445 kJ/mol Mg2+ → Mg3+ + e– IE3 = 7730 kJ/mol* *Core electrons are bound much more tightly than valence electrons Periodic Ionization Trend • Trend: • Period: -

Electronegativity • Covalent Compounds Form Distinct Molecules

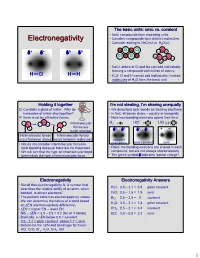

The basic units: ionic vs. covalent • Ionic compounds form repeating units. Electronegativity • Covalent compounds form distinct molecules. • Consider adding to NaCl(s) vs. H2O(s): Cl Cl O δ+ δ– δ0 δ0 Na Na H H Cl Na Cl Na H O O H H H • NaCl: atoms of Cl and Na can add individually forming a compound with million of atoms. HCl HH •H2O: O and H cannot add individually, instead 1 2 molecules of H2O form the basic unit. Holding it together I’m not stealing, I’m sharing unequally Q: Consider a glass of water. Why do • We described ionic bonds as stealing electrons molecules of water stay together? • In fact, all bonds share – equally or unequally. A: there must be attractive forces. • Note how bonding electrons spend their time: + – Intramolecular H2 H H HCl H Cl LiCl [Li] [Cl] forces are 0 0 + – +– much stronger δ δ δ δ Intramolecular forces Intermolecular forces occur between atoms occur between molecules covalent polar covalent ionic • We do not consider intermolecular forces in (non-polar) ionic bonding because there are no molecules. • Point: the bonding electrons are shared in each • We will see that the type of intramolecular bond compound, but are not always shared equally. determines the type of intermolecular force. 3 • The greek symbol δ indicates “partial charge”.4 Electronegativity Electronegativity Answers • Recall that electronegativity is “a number that HCl: 3.0 – 2.1 = 0.9 polar covalent describes the relative ability of an atom, when bonded, to attract electrons”. CrO: 3.5 – 1.6 = 1.9 ionic • The periodic table has electronegativity values. -

Python Module Index 79

mendeleev Documentation Release 0.9.0 Lukasz Mentel Sep 04, 2021 CONTENTS 1 Getting started 3 1.1 Overview.................................................3 1.2 Contributing...............................................3 1.3 Citing...................................................3 1.4 Related projects.............................................4 1.5 Funding..................................................4 2 Installation 5 3 Tutorials 7 3.1 Quick start................................................7 3.2 Bulk data access............................................. 14 3.3 Electronic configuration......................................... 21 3.4 Ions.................................................... 23 3.5 Visualizing custom periodic tables.................................... 25 3.6 Advanced visulization tutorial...................................... 27 3.7 Jupyter notebooks............................................ 30 4 Data 31 4.1 Elements................................................. 31 4.2 Isotopes.................................................. 35 5 Electronegativities 37 5.1 Allen................................................... 37 5.2 Allred and Rochow............................................ 38 5.3 Cottrell and Sutton............................................ 38 5.4 Ghosh................................................... 38 5.5 Gordy................................................... 39 5.6 Li and Xue................................................ 39 5.7 Martynov and Batsanov........................................ -

The Atomic Volume, and Are Held There by the (VERY Dense) Nucleus

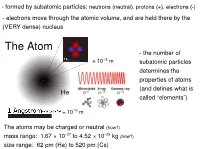

- formed by subatomic particles: neutrons (neutral), protons (+), electrons (-) - electrons move through the atomic volume, and are held there by the (VERY dense) nucleus The Atom - the number of = 10-15 m subatomic particles determines the properties of atoms (and defines what is He called ªelementsº) = 10-10 m The atoms may be charged or neutral (how?) −27 −25 (how?) mass range: 1.67 × 10 to 4.52 × 10 kg size range: 62 pm (He) to 520 pm (Cs) Is it possible to have atoms of the same element with different mass?(Isotopes!) Is it possible to have atoms of the same element with different number of e-? (ions!) Each element has a unique Z Z = number of p+ What property do radioactive elements share? Can you find other elements usually known as pollutants? Why isotopes? Isotopes are great probes for: - past climate: water can be found as H216O, H217O and H218O but H216O (that is, the light isotope) evaporates preferentially. A signal of high H218O in the ocean (at a given time) indicates that a lot of water had evaporated, but not returned to the ocean! (how could this happen?) - human diet: where does our food come from? different plants have a different isotope content What other uses of isotopes do you know that can have an application in environmental sciences? Jahren and Kraft (2008) *mention UCSB project ªChildren of the cornº Can we get energy from atoms? ... fusion and fission ªThe sun is a mass of incandescent gas Your local (still active) A gigantic nuclear furnace G star Where hydrogen is built into helium At a temperature of millions -

Electron Affinity, Electronegativity, Ionization Energy

Electron affinity, Electronegativity, Ionization energy 1. Electron affinity Definition: The energy released when an electron is added to a gaseous atom which is in its ground state to form a gaseous negative ion is defined as the first electron affinity. The symbol is EA, and the unit is kJ/mol. Values and tendencies in the periodic table: The first electron affinities of elements are negative in general except the group VIII and group IIA elements. Because the electron falls into the electrostatic field which is yielded by the atomic nucleus of a neutral atom, and lead to the potential reduction, the energy of this system is reduced. The second electron affinities of all elements are positive. This is because the negative ion is a negative electric field. And if now the other electrons enter the negative field, energy has to be applied to the system to overcome the repulsion that the negative electric field interacts with the electrons. According to the elements of one period, EA generally decreases from the left to the right across the periodic table. According to the elements of one main group, EA generally increases from the top to the bottom of the periodic table. 2. Ionization energy Definition: The ionization energy, EI, of an atom/ion is the minimum energy which is required to remove an electron of an atom. The unit of ionization energy is kJ/mol. Values and tendencies in the periodic table: The first ionization energy is the energy which is required when a gaseous atom/ion loses an electron to form a gaseous +1 valence ion.