Are Pyrrhic) Finding a Plausible Context for RRC 9/1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Herodotos Project (OSU-Ugent): Studies in Ancient Ethnography

Faculty of Literature and Philosophy Julie Boeten The Herodotos Project (OSU-UGent): Studies in Ancient Ethnography Barbarians in Strabo’s ‘Geography’ (Abii-Ionians) With a case-study: the Cappadocians Master thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Linguistics and Literature, Greek and Latin. 2015 Promotor: Prof. Dr. Mark Janse UGent Department of Greek Linguistics Co-Promotores: Prof. Brian Joseph Ohio State University Dr. Christopher Brown Ohio State University ACKNOWLEDGMENT In this acknowledgment I would like to thank everybody who has in some way been a part of this master thesis. First and foremost I want to thank my promotor Prof. Janse for giving me the opportunity to write my thesis in the context of the Herodotos Project, and for giving me suggestions and answering my questions. I am also grateful to Prof. Joseph and Dr. Brown, who have given Anke and me the chance to be a part of the Herodotos Project and who have consented into being our co- promotores. On a whole other level I wish to express my thanks to my parents, without whom I would not have been able to study at all. They have also supported me throughout the writing process and have read parts of the draft. Finally, I would also like to thank Kenneth, for being there for me and for correcting some passages of the thesis. Julie Boeten NEDERLANDSE SAMENVATTING Deze scriptie is geschreven in het kader van het Herodotos Project, een onderneming van de Ohio State University in samenwerking met UGent. De doelstelling van het project is het aanleggen van een databank met alle volkeren die gekend waren in de oudheid. -

A History of the Pyrrhic War

A History of the Pyrrhic War A History of the Pyrrhic War explores the multi-polar nature of a conflict that involved the Romans, peoples of Italy, western Greeks, and Carthaginians during Pyrrhus’ western campaign in the early third century BCE. The war occurred nearly a century before the first historical writings in Rome, resulting in a malleable narrative that emphasized the moral virtues of the Romans, transformed Pyrrhus into a figure that resembled Alexander the Great, disparaged the degeneracy of the Greeks, and demonstrated the mal- icious intent of the Carthaginians. Kent demonstrates the way events were shaped by later Roman generations to transform the complex geopolitical realities of the Pyrrhic War into a one-dimensional duel between themselves and Pyrrhus that anticipated their rise to greatness. This book analyzes the Pyrrhic War through consideration of geopolitical context as well as how later Roman writers remembered the conflict. The focus of the war is taken off Pyrrhus as an individual and shifted towards evaluating the multifaceted interactions of the peoples of Italy and Sicily. A History of the Pyrrhic War is a fundamental resource for academic and learned general readers who have an interest in the interaction of developing imperial powers with their neighbors and how those events shaped the per- ceptions of later generations. It will be of interest not only to students of Roman history, but also to anyone working on historiography in any period. Patrick Alan Kent is an Adjunct Professor at Jackson and Mid-Michigan Colleges in Michigan, USA. His research interests include the development of Roman relations with the peoples of Italy in the fourth and third centuries BCE. -

Ancient Roman Measures Page 1 of 6

Ancient Roman Measures Page 1 of 6 Ancient Rome Table of Measures of Length/Distance Name of Unit (Greek) Digitus Meters 01-Digitus (Daktylos) 1 0.0185 02-Uncia - Polex 1.33 0.0246 03-Duorum Digitorum (Condylos) 2 0.037 04-Palmus (Pala(i)ste) 4 0.074 05-Pes Dimidius (Dihas) 8 0.148 06-Palma Porrecta (Orthodoron) 11 0.2035 07-Palmus Major (Spithame) 12 0.222 08-Pes (Pous) 16 0.296 09-Pugnus (Pygme) 18 0.333 10-Palmipes (Pygon) 20 0.370 11-Cubitus - Ulna (pechus) 24 0.444 12-Gradus – Pes Sestertius (bema aploun) 40 0.74 13-Passus (bema diploun) 80 1.48 14-Ulna Extenda (Orguia) 96 1.776 15-Acnua -Dekempeda - Pertica (Akaina) 160 2.96 16-Actus 1920 35.52 17-Actus Stadium 10000 185 18-Stadium (Stadion Attic) 10000 185 19-Milliarium - Mille passuum 80000 1480 20-Leuka - Leuga 120000 2220 http://www.anistor.gr/history/diophant.html Ancient Roman Measures Page 2 of 6 Table of Measures of Area Name of Unit Pes Quadratus Meters2 01-Pes Quadratus 1 0.0876 02-Dimidium scrupulum 50 4.38 03-Scripulum - scrupulum 100 8.76 04-Actus minimus 480 42.048 05-Uncia 2400 210.24 06-Clima 3600 315.36 07-Sextans 4800 420.48 08-Actus quadratus 14400 1261.44 09-Arvum - Arura 22500 1971 10-Jugerum 28800 2522.88 11-Heredium 57600 5045.76 12-Centuria 5760000 504576 13-Saltus 23040000 2018304 http://www.anistor.gr/history/diophant.html Ancient Roman Measures Page 3 of 6 Table of Measures of Liquids Name of Unit Ligula Liters 01-Ligula 1 0.0114 02-Uncia (metric) 2 0.0228 03-Cyathus 4 0.0456 04-Acetabulum 6 0.0684 05-Sextans 8 0.0912 06-Quartarius – Quadrans 12 0.1368 -

Contesting the Greatness of Alexander the Great: the Representation of Alexander in the Histories of Polybius and Livy

ABSTRACT Title of Document: CONTESTING THE GREATNESS OF ALEXANDER THE GREAT: THE REPRESENTATION OF ALEXANDER IN THE HISTORIES OF POLYBIUS AND LIVY Nikolaus Leo Overtoom, Master of Arts, 2011 Directed By: Professor Arthur M. Eckstein, Department of History By investigating the works of Polybius and Livy, we can discuss an important aspect of the impact of Alexander upon the reputation and image of Rome. Because of the subject of their histories and the political atmosphere in which they were writing - these authors, despite their generally positive opinions of Alexander, ultimately created scenarios where they portrayed the Romans as superior to the Macedonian king. This study has five primary goals: to produce a commentary on the various Alexander passages found in Polybius’ and Livy’s histories; to establish the generally positive opinion of Alexander held by these two writers; to illustrate that a noticeable theme of their works is the ongoing comparison between Alexander and Rome; to demonstrate Polybius’ and Livy’s belief in Roman superiority, even over Alexander; and finally to create an understanding of how this motif influences their greater narratives and alters our appreciation of their works. CONTESTING THE GREATNESS OF ALEXANDER THE GREAT: THE REPRESENTATION OF ALEXANDER IN THE HISTORIES OF POLYBIUS AND LIVY By Nikolaus Leo Overtoom Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2011 Advisory Committee: Professor Arthur M. Eckstein, Chair Professor Judith P. Hallett Professor Kenneth G. Holum © Copyright by Nikolaus Leo Overtoom 2011 Dedication in amorem matris Janet L. -

A Handbook of Greek and Roman Coins

CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND GIVEN IN 1891 BY HENRY WILLIAMS SAGE Cornell University Library CJ 237.H64 A handbook of Greek and Roman coins. 3 1924 021 438 399 Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924021438399 f^antilioofcs of glrcfjaeologj) anU Antiquities A HANDBOOK OF GREEK AND ROMAN COINS A HANDBOOK OF GREEK AND ROMAN COINS G. F. HILL, M.A. OF THE DEPARTMENT OF COINS AND MEDALS IN' THE bRITISH MUSEUM WITH FIFTEEN COLLOTYPE PLATES Hon&on MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited NEW YORK: THE MACMILLAN COMPANY l8 99 \_All rights reserved'] ©jcforb HORACE HART, PRINTER TO THE UNIVERSITY PREFACE The attempt has often been made to condense into a small volume all that is necessary for a beginner in numismatics or a young collector of coins. But success has been less frequent, because the knowledge of coins is essentially a knowledge of details, and small treatises are apt to be un- readable when they contain too many references to particular coins, and unprofltably vague when such references are avoided. I cannot hope that I have passed safely between these two dangers ; indeed, my desire has been to avoid the second at all risk of encountering the former. At the same time it may be said that this book is not meant for the collector who desires only to identify the coins which he happens to possess, while caring little for the wider problems of history, art, mythology, and religion, to which coins sometimes furnish the only key. -

Introduction

Southern Ontario Model United Nations Assembly XLIV Crisis: Second Punic War Introduction: Delegates, Welcome to the Southern Ontario Model United Nations Assembly’s Second Punic War Historical Crisis. The Second Punic War, also known as the Hannibalic War, was a conflict that occurred from 218 – 201 BCE in the Western Mediterranean. The war was fought between Carthage, a dominant commercial empire, and the emerging power of Rome. This conflict marked the second time that the two powers had fought, and with Rome having been victorious in the first Punic War thirty years prior, Carthage was eager for revenge. It also featured the rise to the annals of history a variety of great men, such as legendary Carthaginian general Hannibal Barca and Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus. The rise of Rome in the Western Mediterranean would lead to an epic showdown that would change the course of history. In this particular committee, the SOMA Crisis Staff and Heads will create a simulation of these historical events, hopefully making them as enjoyable and interesting as possible, while maintaining historical fidelity. This background guide will give you a basic Page |1 Southern Ontario Model United Nations Assembly XLIV Crisis: Second Punic War knowledge of both the situation and how you, as a delegate, can influence the Crisis, but further research, as well as inquiry into the process of Crisis is welcome and encouraged. With all this in mind, we are excited to welcome you to SOMA XLIV Crisis Committee and we hope you enjoy your time with us. Margaret Fei Clarke VandenHoven Alec Sampaleanu Helen Kwong Director of Crisis Head of Crisis Jr. -

The Roman Republic S

P1: IML/SPH P2: IML/SPH QC: IML/SPH T1: IML CB598-FM CB598-Flower-v3 August 26, 2003 18:47 The Cambridge Companion to THE ROMAN REPUBLIC S Edited by Harriet I. Flower Princeton University iii P1: IML/SPH P2: IML/SPH QC: IML/SPH T1: IML CB598-FM CB598-Flower-v3 August 26, 2003 18:47 published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru,UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, vic 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcon´ 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Cambridge University Press 2004 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2004 Printed in the United States of America Typeface Bembo 11/13 pt. System LATEX 2ε [tb] A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data The Cambridge Companion to the Roman Republic / edited by Harriet I. Flower. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0-521-80794-8 – isbn 0-521-00390-3 (pb.) 1. Rome – History – Republic, 510–30 b.c. I. Flower, Harriet I. dg235.c36 2003 937.02 – dc21 2003048572 isbn 0 521 80794 8 hardback isbn 0 521 00390 3 paperback iv P1: IML/SPH P2: IML/SPH QC: IML/SPH T1: IML CB598-FM CB598-Flower-v3 August 26, 2003 18:47 Contents S List of Illustrations and Maps page vii List of Contributors ix Preface xv Introduction 1 HARRIET I. -

War and Society in the Roman World

Leicester-Nottingham Studies in Ancient Society Volume 5 WAR AND SOCIETY IN THE ROMAN WORLD WAR AND SOCIETY IN THE ROMAN WORLD Edited by JOHN RICH and GRAHAM SHIPLEY London and New York First published 1993 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2002. Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge Inc. 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 © 1993 John Rich, Graham Shipley and individual contributors All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data War and society in the Roman world/edited by John Rich and Graham Shipley. p. cm.—(Leicester-Nottingham studies in ancient society; v. 5) Selected, revised versions of papers from a series of seminars sponsored by the Classics Departments of Leicester and Nottingham Universities, 1988–1990. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Military art and science—Rome—History. 2. Rome—History, Military. 3. Sociology, Military—Rome—History. I. Rich, John. II. Shipley, Graham. III. Series. U35.W34 1993 355′.00937–dc20 92–36698 ISBN 0-203-07554-4 Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-203-22120-6 -

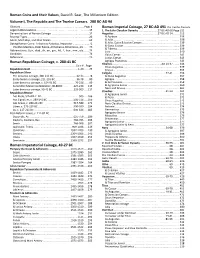

Roman Coins and Their Values, David R. Sear, the Millenium

Roman Coins and their Values , David R. Sear, The Millenium Edition Volume I, The Republic and The Twelve Caesars. 280 BC-AD 96 Glossary ........................................................................ ............ Page 8 Roman Imperial Coinage, 27 BC-AD 491 The Twelve Caesars Legend Abbreviations ................................................... ................... 15 1. The Julio-Claudian Dynasty .........................27 BC-AD 68 . Page 311 Denominations of Roman Coinage .............................. ................... 17 Augustus ...........................................................27 BC-AD 14 ......... 312 Reverse Types ............................................................... ................... 26 & Agrippa ......................................................................... ......... 336 Mints, Mint Map, and Mint Marks................................ ................... 65 & Julia ............................................................................... ......... 338 Dating Roman Coins: Tribunicia Potestas, Imperator .. ................... 72 & Julia, Gaius & Lucius Caesars ........................................ ......... 339 Pontifex Maximus, Pater Patrae, Armeniacus, Britannicus, etc. ....... 73 & Gaius Caesar ................................................................. ......... 339 & Tiberius ......................................................................... ......... 339 Abbreviations: Cuir., diad., dr., ex., gm., hd., l., laur., mm., etc ........ 74 Livia ................................................................................. -

Literary Evidence for Roman Arithmetic with Fractions

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Classical Studies: Faculty Publications and Other Works Faculty Publications 10-2001 Literary Evidence for Roman Arithmetic with Fractions David W. Maher John F. Makowski Loyola University Chicago, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/classicalstudies_facpubs Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons Recommended Citation Maher, DW, and Makowski, JF. "Literary evidence for Roman arithmetic with fractions" in Classical Philology 96(4), 2001. 376-399. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Classical Studies: Faculty Publications and Other Works by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. © University of Chicago Press, 2001. LITERARY EVIDENCE FOR ROMAN ARITHMETIC WITH FRACTIONS DAVID W. MAHER AND JOHN F. MAKOWSKI R OMAN ARITHMETIC IS A PERENNIALLY TROUBLING subject for both classicists and mathematicians.Scholars universally comment on the difficulty posed by Roman alphabetical notation both in expres- sing simple figures and in doing written calculations. For example, Lloyd Motz and Jefferson Weaver with exasperation ask, "How ... can anyone do any arithmetic with DCCCLXXXVIII, the Roman equivalent of 888?," and Florian Cajori concludes that the Romans must have resorted to the abacus in order to multiply a number like 723 (DCCXXIII) by 364 (CCCLXIV).' Yet our sources, literary and inscriptional, indicate that the Romans were capable of highly sophisticated calculations, and, of course, it is well rec- ognized that they had great facility with the abacus and with finger reck- oning. -

Constructing Caesar: Julius Caesar’S Caesar and the Creation of the Myth of Caesar in History and Space

CONSTRUCTING CAESAR: JULIUS CAESAR’S CAESAR AND THE CREATION OF THE MYTH OF CAESAR IN HISTORY AND SPACE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Bradley G. Potter, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2004 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Erik Gunderson, Adviser Professor Fritz Graf ______________________ Professor Ellen O’Gorman Advisor Department of Greek & Latin ABSTRACT Authors since antiquity have constructed the persona of Caesar to satisfy their views of Julius Caesar and his role in Roman history. I contend that Julius Caesar was the first to construct Caesar, and he did so through his commentaries, written in the third person to distance himself from the protagonist of his work, and through his building projects at Rome. Both the war commentaries and the building projects are performative in that they perform “Caesar,” for example the dramatically staged speeches in Bellum Gallicum 7 or the performance platform in front of the temple of Venus Genetrix in the Forum Iulium. Through the performing of Caesar, the texts construct Caesar. My reading aims to distinguish Julius Caesar as author from Caesar the protagonist and persona the texts work to construct. The narrative of Roman camps under siege in Bellum Gallicum 5 constructs Caesar as savior while pointing to problems of Republican oligarchic government, offering Caesar as the solution. Bellum Civile 1 then presents the savior Caesar to the Roman people as the alternative to the very oligarchy that threatens the libertas of the people. -

ATLAS of CLASSICAL HISTORY

ATLAS of CLASSICAL HISTORY EDITED BY RICHARD J.A.TALBERT London and New York First published 1985 by Croom Helm Ltd Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2003. © 1985 Richard J.A.Talbert and contributors All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Atlas of classical history. 1. History, Ancient—Maps I. Talbert, Richard J.A. 911.3 G3201.S2 ISBN 0-203-40535-8 Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-203-71359-1 (Adobe eReader Format) ISBN 0-415-03463-9 (pbk) Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data Also available CONTENTS Preface v Northern Greece, Macedonia and Thrace 32 Contributors vi The Eastern Aegean and the Asia Minor Equivalent Measurements vi Hinterland 33 Attica 34–5, 181 Maps: map and text page reference placed first, Classical Athens 35–6, 181 further reading reference second Roman Athens 35–6, 181 Halicarnassus 36, 181 The Mediterranean World: Physical 1 Miletus 37, 181 The Aegean in the Bronze Age 2–5, 179 Priene 37, 181 Troy 3, 179 Greek Sicily 38–9, 181 Knossos 3, 179 Syracuse 39, 181 Minoan Crete 4–5, 179 Akragas 40, 181 Mycenae 5, 179 Cyrene 40, 182 Mycenaean Greece 4–6, 179 Olympia 41, 182 Mainland Greece in the Homeric Poems 7–8, Greek Dialects c.