From Logic to Animality, Or How Wittgenstein Used Otto Weininger

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wittgenstein's Vienna Our Aim Is, by Academic Standards, a Radical One : to Use Each of Our Four Topics As a Mirror in Which to Reflect and to Study All the Others

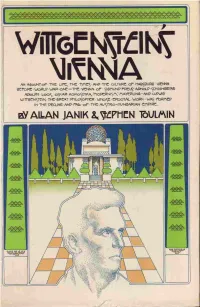

TOUCHSTONE Gustav Klimt, from Ver Sacrum Wittgenstein' s VIENNA Allan Janik and Stephen Toulmin TOUCHSTONE A Touchstone Book Published by Simon and Schuster Copyright ® 1973 by Allan Janik and Stephen Toulmin All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form A Touchstone Book Published by Simon and Schuster A Division of Gulf & Western Corporation Simon & Schuster Building Rockefeller Center 1230 Avenue of the Americas New York, N.Y. 10020 TOUCHSTONE and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster ISBN o-671-2136()-1 ISBN o-671-21725-9Pbk. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 72-83932 Designed by Eve Metz Manufactured in the United States of America 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 The publishers wish to thank the following for permission to repro duce photographs: Bettmann Archives, Art Forum, du magazine, and the National Library of Austria. For permission to reproduce a portion of Arnold SchOnberg's Verklarte Nacht, our thanks to As sociated Music Publishers, Inc., New York, N.Y., copyright by Bel mont Music, Los Angeles, California. Contents PREFACE 9 1. Introduction: PROBLEMS AND METHODS 13 2. Habsburg Vienna: CITY OF PARADOXES 33 The Ambiguity of Viennese Life The Habsburg Hausmacht: Francis I The Cilli Affair Francis Joseph The Character of the Viennese Bourgeoisie The Home and Family Life-The Role of the Press The Position of Women-The Failure of Liberalism The Conditions of Working-Class Life : The Housing Problem Viktor Adler and Austrian Social Democracy Karl Lueger and the Christian Social Party Georg von Schonerer and the German Nationalist Party Theodor Herzl and Zionism The Redl Affair Arthur Schnitzler's Literary Diagnosis of the Viennese Malaise Suicide inVienna 3. -

And “The Jew” in Otto Weininger's Sex and Character

Original citation: Achinger, Christine. (2013) Allegories of destruction : “Woman” and “the Jew” in Otto Weininger's Sex and Character. Germanic Review, Volume 88 (Number 2). pp. 121-149. ISSN 0016-8890 Permanent WRAP url: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/49918/ Copyright and reuse: The Warwick Research Archive Portal (WRAP) makes this work by researchers of the University of Warwick available open access under the following conditions. This article is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported (CC BY 3.0) license and may be reused according to the conditions of the license. For more details see: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ A note on versions: The version presented in WRAP is the published version, or, version of record, and may be cited as it appears here. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] http://go.warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications This article was downloaded by: [137.205.202.200] On: 24 June 2013, At: 03:34 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK The Germanic Review: Literature, Culture, Theory Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vger20 Allegories of Destruction: “Woman” and “the Jew” in Otto Weininger's Sex and Character Christine Achinger a a University of Warwick Published online: 10 Jun 2013. To cite this article: Christine Achinger (2013): Allegories of Destruction: “Woman” and “the Jew” in Otto Weininger's Sex and Character , The Germanic Review: Literature, Culture, Theory, 88:2, 121-149 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00168890.2013.784120 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE For full terms and conditions of use, see: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and- conditions esp. -

Aphoristic Writings, Notebook, and Letters to a Friend, by Otto Weininger

OTTO WEININGER COLLECTED APHORISMS, NOTEBOOK AND LETTERS TO A FRIEND Translated by Martin Dudaniec & Kevin Solway OTTO WEININGER COLLECTED APHORISMS, NOTEBOOK AND LETTERS TO A FRIEND Translated by Martin Dudaniec & Kevin Solway DONATIONS Edition 1.12 Copyright © Kevin Solway & Martin Dudaniec, 2000-2002 All rights reserved.. For information contact: [email protected] ISBN 0-9581336-2-X Contents Introduction by the translators ________________________________________ ii Aphoristic remarks ___________________________________________________1 Last Aphorisms _____________________________________________________29 Notebook __________________________________________________________41 Otto Weininger’s Letters to Arthur Gerber______________________________73 August Strindberg’s Letters about Weininger____________________________92 Appendix – The German Text _________________________________________96 Aphoristisch-Gebliebenes ___________________________________________98 Letzte Aphorismen _______________________________________________121 Taschenbuch ____________________________________________________130 Briefe __________________________________________________________154 Briefe - Otto Weiningers___________________________________________154 Briefe – August Strindbergs________________________________________171 Acknowledgements When we first decided to translate those of Weininger’s writings that had not yet been translated into English, we suspected that if we didn’t then nobody else would. Since then, we discovered that Professor Steven -

Introduction Dissertation Shaun Halper

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Mordechai Langer (1894-1943) and the Birth of the Modern Jewish Homosexual Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5zz859g4 Author Halper, Shaun Jacob Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Mordechai Langer (1894-1943) and the Birth of the Modern Jewish Homosexual By Shaun Jacob Halper A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor John M. Efron, Chair Professor Thomas W. Laqueur Professor Robert Alter Spring 2013 1 Abstract Mordechai Langer (1894-1943) and the Birth of the Modern Jewish Homosexual By Shaun Jacob Halper Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor John M. Efron, Chair This dissertation takes up the first truly Jewish homosexual identity, which Mordechai Jiří Langer (1894-1943) created in Prague during the 1920s. It is a study of the historical conditions— especially the exclusion of Jews by the masculinist wing of the German homosexual rights movement in the two decades bracketing World War One—that produced the need for the articulation of such an identity in the first place. It enters the cultural and intellectual world of fin de siècle homosexuals where “Jews” and “Judaism” were used as foils, against which some homosexuals were defining themselves politically and culturally. Langer defended the Jewish homosexual from German masculinist attack in the form of two literary projects: his theoretical study Die Erotik der Kabbala (1923) and his first volume of Hebrew poetry, Piyyutim ve-Shirei Yedidot (1929). -

Was Wittgenstein a Jew?*

Was Wittgenstein a Jew?* DAVID STERN In my mind's eye, I can already hear posterity talking about me, instead of listening to me, those, who if they knew me, would certainly be a much more ungrateful public . And I must do this: not hear the other in my imagination, but rather myself. Le ., not watch the other, as he watches me - for that is what I do - rather, watch myself. What a trick, and how unending the constant temptation to look to the other, and away from myself . - Wittgenstein, Denkbewegungen: Tagebucher 1930-1932/1936-1937, 15 November or 15 December, 1931 1. Was Wittgenstein Jewish? J Did Ludwig Wittgenstein consider himself a Jew? Should we? Wittgenstein repeatedly wrote about Jews and Judaism in the 1930s (Wittgenstein 1980/ 1998, 1997) and the biographical studies of Wittgenstein by Brian Mc- Guinness (1988), Ray Monk (1990), and B€la Szabados (1992, 1995, 1997, 1999) make it clear that this writing about Jewishness was a way in which he thought about the kind of person he was and the nature of his philosophical work. On the other hand, many philosophers regard Wittgenstein's thoughts about the Jews as relatively unimportant . Many studies of Wittgenstein's philosophy as a whole do not even mention the matter, and those that do usually give it little attention. For instance, Joachim Schulte recognizes that "Jewishness was an important theme for Wittgenstein" (1992, 16-17) but says very little more, except that the available evidence makes precise statements difficult . Rudolf Haller's approach in his paper, "What do Wittgenstein and Weininger have in Common?," is probably more representative of the received wisdom among Wittgenstein experts. -

Pico Della Mirandola Descola Gardner Eco Vernant Vidal-Naquet Clément

George Hermonymus Melchior Wolmar Janus Lascaris Guillaume Budé Peter Brook Jean Toomer Mullah Nassr Eddin Osho (Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh) Jerome of Prague John Wesley E. J. Gold Colin Wilson Henry Sinclair, 2nd Baron Pent... Olgivanna Lloyd Wright P. L. Travers Maurice Nicoll Katherine Mansfield Robert Fripp John G. Bennett James Moore Girolamo Savonarola Thomas de Hartmann Wolfgang Capito Alfred Richard Orage Damião de Góis Frank Lloyd Wright Oscar Ichazo Olga de Hartmann Alexander Hegius Keith Jarrett Jane Heap Galen mathematics Philip Melanchthon Protestant Scholasticism Jeanne de Salzmann Baptist Union in the Czech Rep... Jacob Milich Nicolaus Taurellus Babylonian astronomy Jan Standonck Philip Mairet Moravian Church Moshé Feldenkrais book Negative theologyChristian mysticism John Huss religion Basil of Caesarea Robert Grosseteste Richard Fitzralph Origen Nick Bostrom Tomáš Štítný ze Štítného Scholastics Thomas Bradwardine Thomas More Unity of the Brethren William Tyndale Moses Booker T. Washington Prakash Ambedkar P. D. Ouspensky Tukaram Niebuhr John Colet Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī Panjabrao Deshmukh Proclian Jan Hus George Gurdjieff Social Reform Movement in Maha... Gilpin Constitution of the United Sta... Klein Keohane Berengar of Tours Liber de causis Gregory of Nyssa Benfield Nye A H Salunkhe Peter Damian Sleigh Chiranjeevi Al-Farabi Origen of Alexandria Hildegard of Bingen Sir Thomas More Zimmerman Kabir Hesychasm Lehrer Robert G. Ingersoll Mearsheimer Ram Mohan Roy Bringsjord Jervis Maharaja Sayajirao Gaekwad III Alain de Lille Pierre Victurnien Vergniaud Honorius of Autun Fränkel Synesius of Cyrene Symonds Theon of Alexandria Religious Society of Friends Boyle Walt Maximus the Confessor Ducasse Rāja yoga Amaury of Bene Syrianus Mahatma Phule Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Qur'an Cappadocian Fathers Feldman Moncure D. -

President Herbert Testifies Before Congressional Hearing on Visa Procedures

International News December 2004 President Herbert Testifies before Congressional Hearing on Visa Procedures ver the past year, articles visitors from coming to the United devoted to advancing knowledge of have appeared in the The States. Reminding a packed Senate the world’s major regions. Many IU O Chronicle of Higher hearing room that “hosting foreign area studies programs further Education with headlines such as students is one of the most success- national strategic interests, and “Wanted: Foreign Students,” “No ful elements of our public diplo- international students and faculty Longer Dreaming of America,” and macy” and that “these temporary are significant contributors to the “Security at Home Creates university’s global promi- Insecurity Abroad.” All report nence. He spoke of the significant declines in the “This is a moment for decisive action. contribution of IU’s 4,400 number of international stu- We must return the United States to its international students to dents applying for and being the diversity and quality admitted to U.S. higher edu- preeminence in international education.” of education on IU’s cam- cation institutions. —IU President Adam Herbert puses; of the importance of A survey conducted the interactions and earlier this year by five friendships that bridge the higher-education associations visitors provide enormous economic cultural divide between U.S. and showed that the United States is no and cultural benefits to our country,” foreign students; and of the unique longer regarded as destination of he invited a panel of presidents from knowledge and skills these students choice for attracting the world’s top three major research universities to bring as assistant instructors to IU’s students, largely because of the diffi- testify on the effects of the new visa classrooms, laboratories, and lan- culties they face in obtaining visas. -

Max Nordau and the Making of Racial Zionism Joshua Umland University of Colorado Boulder

University of Colorado, Boulder CU Scholar Undergraduate Honors Theses Honors Program Spring 2013 Max Nordau and the Making of Racial Zionism Joshua Umland University of Colorado Boulder Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.colorado.edu/honr_theses Recommended Citation Umland, Joshua, "Max Nordau and the Making of Racial Zionism" (2013). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 505. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Honors Program at CU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of CU Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Max Nordau and the Making of Racial Zionism By Joshua Umland History and Jewish Studies Departmental Undergraduate Honors Thesis University of Colorado at Boulder April 5, 2013 Thesis Advisor: Dr. David Shneer Departments of History and Department of Jewish Studies Defense Committee: Dr. Patrick Greaney Departments of German and Slavic Languages and Literatures and Department of Humanities Dr. John Willis Department of History 1 2 Table of Contents Abstract 4 Introduction: Muscular Judaism – Racially Based Regeneration 5 Chapter 1 Historiography and Background 8 Chapter 2 Max Nordau’s Background: Racial Discourse and Degeneration 25 Chapter 3 Racial Zionism: Orations and Gymnastics Clubs 37 Chapter 4 E.M. Lilien and the Illustration of a Regenerated Race 54 Conclusion: Racial Zionism 64 Epilogue: The Prophet? 65 Page Numbers of Illustrations Figure 1 Gedenkblatt des Fünften Zionisten-Kongress, E.M. Lilien 11 Figure 2 “From the World of Jewish Gymnastics,”Die Judische Turnzeitung 50 Figure 3 “Well-trained Back and Arm Muscles,” Die Jüdische Turnzeitung 55 Figure 4 “The Creation of Man,” E.M. -

Gender in the Scandinavian Modern Breakthrough

Transgressive Femininity Gender in the Scandinavian Modern Breakthrough Kristina Sjögren UCL PhD in Gender Studies 2 I, Kristina Sjögren, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 3 Abstract This PhD thesis deals with how new discourses on femininity and gender developed in Scandinavian literature during the Modern Breakthrough, 1880-1909. Political, economic and demographic changes in the Scandinavian societies put pressures on the existing, conventional gender roles, which literature reflects; however, literature also created and introduced new discourses on gender. The main focus has been on transgressive female characters in Danish, Swedish and Norwegian novels, which I have seen as indicators of emerging new forms of femininity. The study shows how the transgression of gender boundaries is used in the novels, when presenting their views on what femininity is, should be or could be. In addition to analysing the textual strategies in the representation of these ‘deviant’ literary characters, I have examined how the relevant texts were received by critics and reviewers at the time, as reviews are in themselves discursive constructs. The theoretical basis of this study has mainly been Michel Foucault’s discourse theory, Judith Butler’s theory of performativity and Yvonne Hirdman’s theory of gender binarism. I have also used concepts from several (mainly Anglo-American and Scandinavian) literary gender theorists and historians in the analyses. The four novels analysed in this study are as follows: 1) Danish author Herman Bang’s early decadence novel Haabløse Slægter (1880), where I use a queer theory perspective. -

Four Famous Suicides in History and Lessons Learned: a Narrative Review

Mental Health and Prevention Four famous suicides in history and lessons learned: a narrative review Running Head Famous suicides Andrew J. Hamilton Department of Rural Health, The University of Melbourne, P.O. Box 6500, Shepparton, Victoria 3632, Australia. Email: [email protected] Office of the Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Research and Innovation), Federation University Australia, PO Box 663 Ballarat, Victoria 3353, Australia. Email: [email protected] Keywords: celebrity; Cleopatra; Cobain; death; Hemingway; Socrates. 1 Abstract History can complement the scientific disciplines in teaching us about the nature of suicide. The death of Socrates, especially as described by Xenophon, suggests fear of the frailties of old age as a motive for suicide. A Platonic view implies heroism and martyrdom. Cleopatra’s death and Kurt Cobain’s, signify the importance of losing when the stakes are high, to the extent that the potential loss is simply too great to live with. Hemingway’s death provides strong evidence for a genetic role at play, coupled with various risk factors, most notably mental illness (probably bipolar mood disorder) and setting unrealistic goals. 1.0 Introduction Taking one’s own life seems an incomprehensible proposition to most of us, but globally about 800,000 persons kill themselves each year, and undoubtedly many more attempt suicide and yet more experience suicidal thoughts and suffer attendant psychological stress. The problem has been attacked from many angles, including inter alia, sociological analysis, behavioral analysis, and neuroscience. All of these disciplines have yielded significant insight into this sinister condition, yet it is possible that another discipline, history, has much to offer our understanding of the nature of suicide. -

Barry Smith State University of New York at Buffalo I. Preamble

81 KRAUS ON WEININGER, KRAUS ON WOMEN, KRAUS ON SERBIA Barry Smith State University of New York at Buffalo Most men profess to respect woman theoretically, in order that much more thoroughly to despise her practically; here this relationship has been reversed. Woman could not be highly valued: but women are not for all that to be excluded, from the start and once and for all, from all respect.1 I. Preamble Otto Weininger was born in Vienna on April 3, 1880. The above passage is taken from the only work he published in his lifetime, a big book entitled Geschlecht und Charakter: Eine prinzipielle Untersuchung (roughly: Sex and Character: An Investigation of the Principles). This work contains arguments to the effect that: man alone is rational; there has never been and could never be a woman genius; women, like children, imbeciles, and criminals, should have no voice in human affairs; woman is infinitely porous, infinitely malleable, and infinitely open to external influences; woman has no soul; love and understanding are mutually incompatible; woman is exclusively and continuously a sexual being, man only secondarily and intermittently so; it is the duty of all women to strive to become men; every man, even Goethe, even Napoleon, even Kant, is part woman; women do not exist. Writing the Austrian Traditions: Relations between Philosophy and Literature. Ed. Wolfgang Huemer and Marc-Oliver Schuster. Edmonton, Alberta: Wirth-Institute for Austrian and Central European Studies, 2003. pp. 81-100. 82 BARRY SMITH At the age of twenty-two, Weininger received from the University of Vienna the degree of Doctor of Philosophy summa cum laude for a dissertation on the biology, psychology, and sociology of the sexes entitled “Eros and Psyche.” On the same day he converted to Protestantism – something highly unusual for a Jew in Catholic Austria. -

Hans Kelsen's Political Realism

HANS KELSEN’S POLITICAL REALISM 66520_Schuett.indd520_Schuett.indd i 226/11/206/11/20 11:50:50 PPMM 66520_Schuett.indd520_Schuett.indd iiii 226/11/206/11/20 11:50:50 PPMM HANS KELSEN’S POLITICAL REALISM Robert Schuett 66520_Schuett.indd520_Schuett.indd iiiiii 226/11/206/11/20 11:50:50 PPMM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com © Robert Schuett, 2021 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road, 12(2f) Jackson’s Entry, Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 10/12.5 Adobe Sabon by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain. A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 8168 7 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 8170 0 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 8171 7 (epub) The right of Robert Schuett to be identifi ed as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). 66520_Schuett.indd520_Schuett.indd iivv 226/11/206/11/20 11:50:50 PPMM CONTENTS Introduction 1 CHAPTER 1 KELSEN’S ENEMIES 8 1 The FBI 8 2 Realists versus Kelsen 13 3 Imaginary Foe 22 4 There Is No Utopia 27 5 A Most Misunderstood Man 34 CHAPTER 2 KELSEN’S MILIEU 36 6 The k.