Annual Progress/Final Progress Report Format

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Watergore Trial Orchard

NACM Short Report 5.5 Liz Copas 2005 WATERGORE TRIAL ORCHARD NOTE This trial site no longer exists and unfortunately some of the LA Disease Resistant seedling were grubbed out. Propagating material is still available of most of the other cultivars mentioned. SUMMARY Planted 1990 Main orchard planted to double rows N/S of Major, Ashton Bitter, Ellis Bitter and White Jersey at 18 x 8 on M25. This rootctock has proved rather too vigorous for the good soil on this site. In retrospect more effort was needed to control the early growth of these trees and induce cropping. The pruning trial [NACM 95/5/1] demonstrated some response to belated pruning to centre leader and bending or tying down strong lateral branches. This has served as a useful model for other orchards of these varieties. Planted 1995 Selected early harvesting seedlings from the Long Ashton [LA 1978] breeding program; 2 bittersweet, 4 sharps and 1 sweet, planted E/W on MM 106. Poor tree shape and excessively early flowering has ruled out many of these. The best are LA 13/2 and LA 13/7, Tremletts crosses with a strong resemblance to the parent but with some resistance to scab and mildew. Both need some initial tree training but could be kept annual. Planted 1996 Selected old varieties with some potential for bush orchards were planted on MM 106 . Of these the most promising are Broxwood Foxwhelp and possibly the other Foxwhelps [all bittersharps], also Don's Seedling [bittersweet] and Crimson King [sharp] as early harvesting varieties. Both Severn Banks [sharp] and Black Dabinett [bittersweet] could make useful late harvesting varieties. -

The Marlboro Mixer

Sept/Oct 2013 Volume 10, Issue 5 The Marlboro Mixer A FREE newsletter for the town of Marlboro, Vermont. 31st Annual Marlboro Community Fair, September 14th!! In this Issue: Marlboro Cares….2 The Fair is almost here! Please join us on Saturday, September 14th. Select Board……….3 This year we are celebrating “The Makers of Marlboro,” all of those Store…………………..3 friends and neighbors who build, create, craft, make, sing, strum, write, Apples………….…….4 repair, harvest, raise, bake, imagine... MES……………………5 Poetry……………..…6 This year we are very glad to have a number of demonstrations of the skill and ingenuity that make Energy……………….6 our Town such a unique place. The Arts & Crafts Tent will host exhibits of wool yarn spinning, toy VPL……………..…….7 making, an oral history, tool sharpening, video productions, and others. Come learn about birds of prey and enjoy a hard cider or maple syrup tasting in the Ag Tent. We encourage everyone to bring flowers, fruits, and vegetables, as well as jams and beers, for display and to enter to win prizes - and entries from all ages are welcome, so please come and bring the best of your harvest. We are glad once again to be hosting a baking contest with prizes donated by King Arthur Flour, with entries being accepted up to 9:30 AM. The stage will be packed with great music all day long, including Rich Grumbine, Singcrony, Michael Hertz, T. Fredric and Lillian Jones, Jesse Lepkoff and friends, the MacArthur Family, Julia Slone, and Red Heart the Ticker. We will have a poetry reading at 3:00 and wrap up the day with A FREE newsletter the Fair Song at 4:00. -

Apples: Organic Production Guide

A project of the National Center for Appropriate Technology 1-800-346-9140 • www.attra.ncat.org Apples: Organic Production Guide By Tammy Hinman This publication provides information on organic apple production from recent research and producer and Guy Ames, NCAT experience. Many aspects of apple production are the same whether the grower uses low-spray, organic, Agriculture Specialists or conventional management. Accordingly, this publication focuses on the aspects that differ from Published nonorganic practices—primarily pest and disease control, marketing, and economics. (Information on March 2011 organic weed control and fertility management in orchards is presented in a separate ATTRA publica- © NCAT tion, Tree Fruits: Organic Production Overview.) This publication introduces the major apple insect pests IP020 and diseases and the most effective organic management methods. It also includes farmer profiles of working orchards and a section dealing with economic and marketing considerations. There is an exten- sive list of resources for information and supplies and an appendix on disease-resistant apple varieties. Contents Introduction ......................1 Geographical Factors Affecting Disease and Pest Management ...........3 Insect and Mite Pests .....3 Insect IPM in Apples - Kaolin Clay ........6 Diseases ........................... 14 Mammal and Bird Pests .........................20 Thinning ..........................20 Weed and Orchard Floor Management ......20 Economics and Marketing ........................22 Conclusion -

Survey of Apple Clones in the United States

Historic, archived document Do not assume content reflects current scientific knowledge, policies, or practices. 5 ARS 34-37-1 May 1963 A Survey of Apple Clones in the United States u. S. DFPT. OF AGRffini r U>2 4 L964 Agricultural Research Service U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE PREFACE This publication reports on surveys of the deciduous fruit and nut clones being maintained at the Federal and State experiment stations in the United States. It will b- published in three c parts: I. Apples, II. Stone Fruit. , UI, Pears, Nuts, and Other Fruits. This survey was conducted at the request of the National Coor- dinating Committee on New Crops. Its purpose is to obtain an indication of the volume of material that would be involved in establishing clonal germ plasm repositories for the use of fruit breeders throughout the country. ACKNOWLEDGMENT Gratitude is expressed for the assistance of H. F. Winters of the New Crops Research Branch, Crops Research Division, Agricultural Research Service, under whose direction the questionnaire was designed and initial distribution made. The author also acknowledges the work of D. D. Dolan, W. R. Langford, W. H. Skrdla, and L. A. Mullen, coordinators of the New Crops Regional Cooperative Program, through whom the data used in this survey were obtained from the State experiment stations. Finally, it is recognized that much extracurricular work was expended by the various experiment stations in completing the questionnaires. : CONTENTS Introduction 1 Germany 298 Key to reporting stations. „ . 4 Soviet Union . 302 Abbreviations used in descriptions .... 6 Sweden . 303 Sports United States selections 304 Baldwin. -

HOW to Eat Crabs!

washingtonFAMILY.com JULY 2019 HOW to Eat Crabs! STUDENT-CENTERED LEARNING AT ONENESS-FAMILY SCHOOL Kenwood School Dedicated to Educational Excellence for over 50 years BEFORE & AFTER SCHOOL CARE KINDERGARTEN THRU 6TH GRADE LEARNING • Small class sizes — allows one-on-one instruction with the teacher • Follows and exceeds Fairfax County curriculum • Standardized testing twice a year to evaluate school ability and achievement; no SOL’s • Integration of reading, writing, oral language, phonics, science, social studies, spelling and math • Extracurricular classes in computers, music, gym and Spanish • Manners and strong social skills are developed in everyday interactions Kindergarten cut o November 30th play • On-site gym for indoor exercise Kindergarten • Daily indoor/outdoor free play cut o • Spacious playground November 30th Extras • Daily interactions with your child’s teacher • Invention Convention, Science Fairs, Fall Festival • Children are able to excel at their own pace • Hot catered lunches and snacks provided • Variety of educational fi eld trips throughout the year • Summer / Holiday Camps • Centrally located — minutes from downtown and major highways 703-256-4711 4955 Sunset Lane Annondale, VA [email protected] www.kenwoodschool.com mommy & me JULY 17TH jokes & WEDNESDAY · 11AM COMMUNITY ROOM juggles Enjoy Mommy’s Lounge while your children play and nurture their magical & creative side. Interactive entertainment provided by Mandy Dalton. Enjoy exclusive discounts from retailers and refreshments provided by Starbucks Coffee and Auntie Anne’s Pretzel Perfect/Planet Smoothie I-95 & I-295 | 6800 Oxon Hill Road | (301) 567-3880 | TangerOutlets.com 51488_NAT_Mommy&Me_PrintAd_7x10_FIN.indd 1 6/19/19 1:24 PM CONTENTS JULY 2019 ON THE COVER STUDENTS AT THE ONENESS-FAMILY SCHOOL Keep your child learning all summer long. -

The Craft Cider Revival – Some Technical Considerations Andrew Lea 28/2/2007 1

The Craft Cider Revival – Some Technical Considerations Andrew Lea 28/2/2007 1 THE CRAFT CIDER REVIVAL ~ Some Technical Considerations Presentation to SWECA 28th February 2007 Andrew Lea SOME THINGS TO THINK ABOUT Orcharding and fruit selection Full juice or high gravity fermentations Yeast and sulphiting Keeving Malo-lactic maturation Style of finished product What is your overall USP? How are you differentiated? CRAFT CIDER IS NOW SPREADING Cidermaking was once widespread over the whole of Southern England There are signs that it may be returning eg Kent, Sussex and East Anglia So regional styles may be back in favour eg higher acid /less tannic in the East CHOICE OF CIDER FRUIT The traditional classification (Barker, LARS, 1905) Acid % ‘Tannin’ % Sweet < 0.45 < 0.2 Sharp > 0.45 < 0.2 Bittersharp > 0.45 > 0.2 Bittersweet < 0.45 > 0.2 Finished ~ 0.45 ~ 0.2 Cider CHOICE OF “VINTAGE QUALITY” FRUIT Term devised by Hogg 1886 Adopted by Barker 1910 to embrace superior qualities that could not be determined by analysis This is still true today! The Craft Cider Revival – Some Technical Considerations Andrew Lea 28/2/2007 2 “VINTAGE QUALITY” LIST (1988) Sharps / Bittersharps Dymock Red Kingston Black Stoke Red Foxwhelp Browns Apple Frederick Backwell Red Bittersweets Ashton Brown Jersey Harry Masters Jersey Dabinett Major White Jersey Yarlington Mill Medaille d’Or Pure Sweets Northwood Sweet Alford Sweet Coppin BLENDING OR SINGLE VARIETALS? Blending before fermentation can ensure good pH control (< 3.8) High pH (bittersweet) juices prone to infection Single varietals may be sensorially unbalanced unless ameliorated with dilution or added acid RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN pH AND TITRATABLE ACID IS NOT EXACT Most bittersweet juices are > pH 3.8 or < 0.4% titratable acidity. -

Agriculture Facts and Figures

Michigan Agriculture Facts & Figures Michigan grows a wide variety of crops each year and our farmers take pride in growing high-quality, diverse products. The state leads the nation in the production of several crops, including asparagus; black and cranberry beans; cucumbers; tart cherries; Niagara grapes; and squash. Michigan agriculture contributes more than $104.7 billion annually to our state’s economy, second in diversity only to California. We invite you to learn more about our state’s agriculture production and to enjoy all the bounty and beauty Michigan’s agriculture industry has to offer. Michigan Department of Agriculture & Rural Development PO Box 30017 Lansing, MI 48909 Toll-Free: 800-292-3939 www.michigan.gov/agdevelopment The facts and figures in this booklet are sourced from USDA NASS for 2016 and 2018. Seasonality Michigan apples are harvested August through October, but with controlled-atmosphere storage technology, they are available nearly year-round. Apples Processed apples are available throughout the year in juice, Apples are one of the largest and most valuable fruit canned, fresh slices, and applesauce forms. crops grown in Michigan. In 2018, 1.050 billion pounds of apples were harvested in Michigan, ranking third in Nutrition the nation. About 50 percent of the harvest was used Apples are naturally free from for processing. There are more than 11.3 million apple fat, cholesterol, and sodium. trees in commercial production, covering 35,500 acres They are an excellent source on 825 family-run farms. Orchards are trending to of fiber. super high-density planting (approximately 1,000 or more trees per acre) which come into production and Contact bring desirable varieties to market quickly. -

Characterization of Malus Genotypes Within the Usda-Pgru Malus Germplasm Collection for Their Potential Use Within the Hard Cider Industry

CHARACTERIZATION OF MALUS GENOTYPES WITHIN THE USDA-PGRU MALUS GERMPLASM COLLECTION FOR THEIR POTENTIAL USE WITHIN THE HARD CIDER INDUSTRY A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science by Nathan Carey Wojtyna August 2018 © 2018 Nathan Carey Wojtyna ABSTRACT In the United States, hard cider producers lack access to apple genotypes (Malus ×domestica Borkh. and other Malus species) that possess higher concentrations of tannins (polyphenols that taste bitter and/or astringent) and acidity (described as having a sharp taste) than what is typically found in culinary apples. Utilizing the USDA-PGRU Malus germplasm collection, two projects were conducted to address these concerns. The first project characterized fruit quality and juice chemistry for a target population of 308 accessions with the goal of identifying accessions with desirable characteristics for hard cider production. The second project used the same sample population to explore the use of the Ma1 and Q8 genes as potential markers to predict the concentration of titratable acidity of cider apples. An initial target population of 308 accessions were identified and 158 accessions were assessed in 2017 for external and internal fruit characteristics along with juice chemistry. As per the Long Ashton Research Station (LARS) cider apple classification system where apples with tannin concentration (measured with the Löwenthal Permanganate Titration method) greater than 2.0 g×L-1 are classified as bitter, and those with a malic acid concentration greater than 4.5 g×L-1 are classified as sharp, 29% of the 158 accessions would be classified as bittersweet, 13% bittersharp, 28% sweet (neither bitter nor sharp), and 30% sharp. -

The Wingfoot Clan - August 4, 1966 - Page 3

.... - .......·-· , z <1,; .... I.042,'-•L.,· .042042·042.... - - ./1.- 1·415 -<&2:- ./ I ...... + 2./1 "ING= :•CIT<1••tr:SrA r• LAN 1'' I '4 I ' ..1 '1 t*» ., « Ii U Y,9'* TH" 0/' EAR TIRE & RUBBER COMPANY AKRON EDITION ..»7 *f 44 ** V 01. 5 Akron, Ohio (3.-ti•ip August 4, 1966 No.31 :<fi) -- S THIS THE CLUB? Pam- e Moore ponders as she Teys a big problem - how 'e:...v» . Sales & Earnings Again get this giant ball in the - . .... 4....'::, " Pamela is just one of I + 07:, empl()yes' children to : n a weekly Rolf ..r. - .... e the others and Top All Previous Records /./. 4 2 2 b problems, turn .. ,'. The highest sales and earnings in history Goodyear's record quarterly earnings of •lit . 1- $33,589,000 were equivalent to 93 cents a ..'-34 i: .4/. -- were achieved by Goodyear during the first + - 1 - .- .-1-&44-.00 . I i .-'.*6 9, ..G.-.-'1•.1.•=••'- .... 4**4 42.4.-. six months and the second quarter of 1966, share, based on 35,792,174 shares outstand- ing June 30, 1966. They were 17.4 per cent \ 1.A- Russell DeYoung, chairman and chief ex- ,/). 6-... ecutive officer, announcd. higher than the $28,606,000, or 80 cents a share, recorded in the second quarter of 1965. Spurred by gains in virtually all lines of 1 The previous record for quarterly earnings " .'*V- ........ activity worldwide, the company recorded 41 I. was $31,215,000, achieved in the last three • six-month sales of $1,220,472,000 and net aA months of 1965. -

Genetic Analysis of a Major International Collection of Cultivated Apple Varieties Reveals Previously Unknown Historic Heteroploid and Inbred Relationships

Genetic analysis of a major international collection of cultivated apple varieties reveals previously unknown historic heteroploid and inbred relationships Article Published Version Creative Commons: Attribution 4.0 (CC-BY) Open Access Ordidge, M., Kirdwichai, P., Baksh, M. F., Venison, E. P., Gibbings, J. G. and Dunwell, J. M. (2018) Genetic analysis of a major international collection of cultivated apple varieties reveals previously unknown historic heteroploid and inbred relationships. PLoS ONE, 13 (9). e0202405. ISSN 1932-6203 doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202405 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/78594/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202405 Publisher: Public Library of Science All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online Genetic analysis of a major international collection of cultivated apple varieties reveals previously unknown historic heteroploid and inbred relationships Article Creative Commons: Attribution 4.0 (CC-BY) Ordidge, M., Kirdwichai, P., Baksh, M. F., Venison, E. P., Gibbings, J. G. and Dunwell, J. M. (2018) Genetic analysis of a major international collection of cultivated apple varieties reveals previously unknown historic heteroploid and inbred relationships. PLOS ONE, 13 (9). -

Worcestershire Cider Product Specification

PRODUCT SPECIFICATION “Worcestershire Cider” PDO ( ) PGI (D) 1. Responsible department in the Member State: Name: Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) Area 3A Nobel House Smith Square London SW1P 3JR United Kingdom Tel: 0207 238 6075 Fax: 0207 238 5728 Email: [email protected] 2. Applicant Group: Name: The Herefordshire, Worcestershire and Gloucestershire Cider and Perry Makers Address: c/o G C Warren, H Weston and Sons Ltd The Bounds Much Marcle Herefordshire HR2 2NQ Tel: Fax: Email: Composition: Producer/processors (12) Other ( ) 3. Type of product: Cider - Class 1.8 (Other) 1 4. Specification (summary of requirements under Art 7(1) of Regulation (EU) No 1151/2012) 4.1. Name: “Worcestershire Cider” 4.2. Description: A traditional cider prepared by fermentation of the juice of locally grown bitter-sweet, bitter-sharp, sweet and sharp traditionally used cider apples, with or without the addition of up to 25% perry pear juice; chaptalisation is permitted to bring the potential alcohol level to ca 9.5% ABV prior to final blending of the cider. Ciders exhibit rich appley flavours, with marked astringency and with a balance between sweetness and bitterness. Products may be either medium sweet or dry (with regard to sweetness). Actual alcohol content by volume 4.0-8.5% Specific gravity at 20̊C 0.996-1.022 Sugar content 0.55g/1 Sugar-free dry extract >13g/1 Total acidity (as Malic Acid) 40-60 mEq/1 Volatile acidity (as Acetic Acid) <1.4g/1 Iron content <7mg/kg Copper content <2mg/kg Arsenic content <0.2mg/kg Lead content <0.2mg/kg Total Sulphur Dioxide <200mg/1 Free Sulphur Dioxide 40-60mg/1 4.3. -

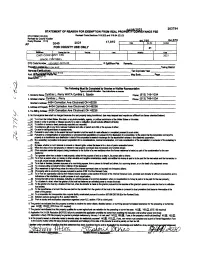

04/08/2021 Year Countynumber 31 Number

263794 STATEMENT OF REABON FOR EXEMPTION FROM REAL PROP#RfauyANCE FEE OTE FORM 100 (EX) RevII,d Code Sections 319.202 and 319.54 (G) (3) Revisid by County Auditor Dusty Rhodes 11/12 66.760 84,570 2021 17,810 1 D- Co. la Numbs, AF 3040 1 FOR COUNTY USE ONLY 31 A66.. T.Ung Dlet No. Tax 1* Bulldng Total CINTI CORP-(INTI CSD 2021 SPAnf CYNTHIA L DTE Code Number 180-OA81-0075-00 0 SPHUNew Plat Remalks: ROP|*198»'.MKFION A\/F Taxing District Narne®Xem,plicate Tax Duplicate Year Acct. 8*611TigAUFT E Map Book page Descrl;RETTI (9 Thi Following Must BI Compl,tod by Grantee or Hls*Her Represintatlve Typs orpIN d In#Innalon. 5,0 In#„EASons on Mine. 1, Grantofs N,ne: Cynthia L. Perry WATA Cynnla L. Spade Phone: (513) 748-1034 2. Grant,0'8 Name: Cynthia L. Perry Phone: (513) 748-1034 Gran*8 Addross: 4434 Camation Ave Cincinnati OH 45238 3. Address 01 Plopelly: 4434 Camation Ave Cincinnati OH 45238 4, Tax ailing Addis: 4434 Carnation Ave Cincinnati OH 45238 5. No Convoyance 100, shall be charged because the real prope,4 being hnsferred: (wo mq request and requirl an amdavlt on lms checked below) Us) To or frorn 08 United Stilm, thts state, or any hamentality, agincy, or pollocal subdlviston of the llilted Stat,6 or thls :tate; h _lb) Soldyin order to providior Mloase secl*lor a debt or obllgaion; (muillneludiamdevitoffhc,1) 1(c) To con#trn or correct a deed previously execulid and recorded; A _(d) To evidence 8 glft, in any fonn, beh,-n husband and w#B, or parent and dilld or tte spouse of •1er; _(0) Onsalifor delinqulnt lax,8 or.,omment,; _(f) Pursuant to court order, to #te dint thst such *slw 18 noi the muit of a sale ellegled or complet,d purtuant to such order; Ug) Pursuant toi leargankation of corporabs or uninootporatidis,ociations or pursuarito the (Ns,oh*on of a corporadon, to the e,dent that the corporation COrNeys the 0'\ properly to a stocltolder as a ¢1*lbudon in Idnd of the corpor@Uon's assets in exchange for the *dholder's shares In the dissolved corpor:San; _(Jt) By asublidiary , .