Discussion Paper 18: Farmer Collectives: a Case Study on Kudumbashree, VFPCK and Fpcs in Kerala

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thrissur District

Coconut Producers’ Federations - Thrissur District Area of Operation No of No of No of Annual S. Name of the CPF and Contact Address of memb Farme Bearing Production NO Panchyat President (with Mobile No and E. mail) Block Taluk er rs palms Nuts (Nos) (s) CPS’s Shri. Sadhanandan, President Perinjanam Nalikera Ulpadaka Federation Perinjana Mathil Kodung 1 15 1033 47842 1617495 Valiyaparambil (H), Perinjanam West PO, Thrissur m akam allur – 680 686 Mob: 9846982296 Shri. Mohanan, President Sreenarayanapuram Federation of Coconut Mathil Kodung 2 SN Puram 17 1020 58518 2414095 Producers Society , Kanicheydath (H), akam allur P. Vemballoor PO, Thrissur- 680 671 Mob: 9496751138 Shri. M.A Vijayan, President Mathilakam Federation of Coconut Producers Mathilaka Mathil Kodung 3 14 1067 52532 1725840 Society , Mundengattu (H), PO Kulimuttom m akam allur Thrissur – 680 691, Mob: 9447236905 Shri. Hiran Kozhiparambiil, President Kaipamangalam Federation of Coconut Kaipaman Mathil Kodung 13 946 46000 1797898 4 Producers Society , PO Kaipamangalam Beach galam akam allur Thrissur – 680 681, Mob: 9446424460 Shri. V.A. Kochumoideen, President Kairali Federation of Coconut Producers Mathil Kodung 5 Eriyad 15 975 43161 1311618 Societies , Valiyakath (H) PO, Azhikode, Thrissur - akam allur 680666 Mob: 9447717044 Shri. C.P. Ramakrishnan, President Oruma Nattika Grama Panchayath Federation Thalik Chavakk 6 Nattika 11 934 41287 1671889 of Coconut Producers Societies , ulam ad Chechiparambil (H), Nattikka PO, Thrissur – 680657 Mob: 9497461616 Shri. Yousef.A.A., President Edathiruthy Federation of Coconut Producers Edathiruth Mathil Kodung 7 10 832 43862 1693215 Societies , Chentrasppinni East, Thrissur – 680687 y akam allur Mob: 9645258811 Shri. K.M. Gopalan, President Vatanappilly Federation of Coconut Producers Vatanappill Thalik Chavakk 8 10 784 52362 3019441 Societies , Kalavoor (H), PO Vatanappilly Beach, y ulam ad Thrissur – 680 614, Mob: 9446445799 Shri. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Thrissur Rural District from 29.11.2020To05.12.2020

Accused Persons arrested in Thrissur Rural district from 29.11.2020to05.12.2020 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 29-11-2020 1050/2020 CHERPU UNNIKRISH MOHANDA 50, URAKATH HOUSE PERINCHER BAILED BY 1 APPU at 21:35 U/s 118(e) of (Thrissur NAN S Male , PERINCHERY RY POLICE Hrs KP Act Rural) SI OF POLICE 1281/2020 U/s 269, 270 IPC & 118(e) of KP Act & ANANDAKR MATHILAK POOVALIPARAMB 29-11-2020 Sec. 4(2)(f) ISHNAN SHAMSUDE 56, AM BAILED BY 2 ABDU IL HOUSE, AMANDOOR at 20:30 r/w 5 of ISHO EN Male (Thrissur POLICE PORIBAZAR Hrs Kerala MATHILAKA Rural) Epidemic M PS Diseases Ordinance 2020 THEKKOTTU 991/2020 U/s HOUSE, PARAMBI 29-11-2020 ALOOR SUKUMARA 35, PARAMBI 4(2)(e)(j)r/w SREEJITH.AK BAILED BY 3 ARUN ROAD DESAM, at 20:50 (Thrissur N Male ROAD 3(a) of KEDO SI OF POLICE POLICE THAZHEKKAD Hrs Rural) 2020 VILLAGE THEKKOTU 991/2020 U/s HOUSE,THAZHEK 29-11-2020 ALOOR 38, PARAMBI 4(2)(e)(j)r/w SREEJITH.AK BAILED BY 4 SAJI MOHANAN AD at 20:50 (Thrissur Male ROAD 3(a) of KEDO SI OF POLICE POLICE DESHAM,THAZHE Hrs Rural) 2020 KAD VILLAGE 1280/2020 U/s 269, 270 IPC & 118(e) RAMANKULATH of KP Act & MATHILAK HOUSE, EMMAD 29-11-2020 Sec. -

Protection of Tsunami Affected Coastal Areas by Establishing Bio-Shield Through People’S Participation

KFRI Research Report No. 362 ISSN No. 0970-8103 Protection of Tsunami Affected Coastal Areas by Establishing Bio-shield through people’s participation Seethalakshmi K. K. Raveendran V. P and Balagopalan M Sustainable Forest Management Division Kerala Forest Research Institute Peechi, Thrissur, Kerala Kerala State Council for Science, Technology and Environment, Sasthra Bhavan, Thiruvananthapuram December – 2010 Contents Acknowledgements Project proposal Abstract…………… 1 Introduction ……………………3 Materials and methods Species, source of planting material and nursery sites …5 Nursery technology …………6 Planting ……………7 Enumeration of planted area………8 Soil sampling and analysis ………9 Plant sampling and analysis………10 Results Awareness programme ………11 Nursery establishment and seedling production…….12 Planting……………13 Mixed bio-shield ……14 Maintenance ……………15 Enumeration……… 15 Soil analysis………16 Plant analysis………16 Establishment of bio-shield………17 Discussion …………..18 References…………20 Acknowledgements We sincerely acknowledge the continuous support received from Sri. K. P. Rajendran and Sri. Mullakkara Retnakaran Hon’ble Ministers for Revenue Agriculture respectively, Shri. T N Prathapan, MLA, Nattika and Shri K. V. Abdul Khader MLA, Guruvayoor during the implementation of the project. Special acknowledgement is due to Dr. Niveditha Haran IAS, Additional Chief Secretary, and all the staff of Revenue and Disaster Management Department, Government of Kerala for their strenuous efforts during evaluation and timely interventions that contributed for achieving the time target of the project. The support received from Dr. CTS Nair, Executive Vice President Dr. E. P. Yesodharan, Former Executive Vice President, Dr. P. Harinarayanan, Scientific Officer, Kerala State Council for Science, Technology and Environment, Sasthra Bhavan, Thiruvananthapuram during various stages of implementation of the project was real inspiration and we owe special thanks to them. -

Research Paper Botany a Detailed Survey on Sacred Groves of Different Extends in the Coastal Belt of Thrissur District,Kerala,India

Volume-4, Issue-11, Nov-2015 • ISSN No 2277 - 8160 Research Paper Botany A Detailed Survey on Sacred Groves of Different extends in the Coastal Belt of Thrissur District,Kerala,India Research Scholar in PG Dept of Botany and Research, S.N.College, Jincy.T.S Nattika, Thrissur, University of Calicut,Kerala, India Assistant Professor in PG Dept of Botany and Research, S.N.College, Subin.M.P Nattika, Thrissur, University of Calicut, Kerala, ABSTRACT Sacred groves represent a major effort to recognize and conserve ethnic biodiversity traditionally. As an ecosystem, they even help in soil and water conservation besides preserving the rich biological diversity and microclimatic conditions of the region. Now a day the environmental significance of the sacred groves is a matter well forgotten and are gradually disappearing under the influence of changing socioeconomic scenario, disappearance of the tharavadu system, shift in belief systems, development projects and other anthropogenic activities, and many of them are now just relics of a once-gregarious vegetation. Under these circumstances, preservation, conservation and management of these groves warrant top priority. However no concrete steps are being initiated to protect and conserve these groves and this may be mainly due to lack of awareness regarding the environmental significance of sacred groves by the local people together with lack of proper information regarding their existence in the region by the public and concerned agencies who are entrusted to safe guard the existing groves in the region. If concrete steps are not taken to stop their deterioration, these micro cosmos will disappear from the face of earth, resulting in loss of biodiversity which may include valuable species of flora and fauna and finally cause imbalance in the ecosystem. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Thrissur Rural District from 15.04.2018 to 21.04.2018

Accused Persons arrested in Thrissur Rural district from 15.04.2018 to 21.04.2018 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 MARATH HOUSE, 15.04.201 CR.303/18 GANGADHAR 50/18 SANEESH.S.R JFCM NO II 1 SUNIL ANTHIKKAD ANTHIKAD 8 AT 15.40 U/S 7 & 8 OF ANTHIKAD AN MALE SI OF POLICE THRISSUR THRISSUR HRS KG ACT PANDARAN HOUSE, 15.04.201 CR.303/18 39/18 ANTHIKKAD DESAM, SANEESH.S.R JFCM NO II 2 ANIL LALSING ANTHIKAD 8 AT 15.40 U/S 7 & 8 OF ANTHIKAD MALE ANTHIKKAD SI OF POLICE THRISSUR HRS KG ACT VILLAGE THRISSUR VALATH HOUSE, 15.04.201 CR.303/18 SHANMUGH 35/18 ANTHIKKAD SANEESH.S.R JFCM NO II 3 SHIBIN ANTHIKAD 8 AT 15.40 U/S 7 & 8 OF ANTHIKAD AN MALE DESAM,ANTHIKKAD SI OF POLICE THRISSUR HRS KG ACT VILLAGE THRISSUR THATTIL HOUSE, 15.04.201 CR.303/18 PRABHAKAR 48/18 ANTHIKKAD DESAM, SANEESH.S.R JFCM NO II 4 PRASHEED ANTHIKAD 8 AT 15.40 U/S 7 & 8 OF ANTHIKAD AN MALE ANTHIKKAD SI OF POLICE THRISSUR HRS KG ACT VILLAGE THRISSUR NECHIKKOTT 15.04.201 CR.303/18 GOPALAKRIS 36/18 HOUSE, ANTHIKKAD SANEESH.S.R JFCM NO II 5 UDAYAN ANTHIKAD 8 AT 15.40 U/S 7 & 8 OF ANTHIKAD HNAN MALE DESAM, ANTHIKKAD SI OF POLICE THRISSUR HRS KG ACT VILLAGE THRISSUR MAMPULLY HOUSE, 15.04.201 CR.303/18 SIAVARAMA SANKARAN 68/18 ANTHIKKAD DESAM, SANEESH.S.R JFCM NO II 6 ANTHIKAD 8 AT 15.40 U/S 7 & 8 OF ANTHIKAD N KUTTI MALE ANTHIKKAD SI OF -

KSEB Electrical Section Codes

SMS Format -> KSEB <Space> Section Code<Space> Consumer No -> 537252 KSEB Electrical Section Codes Section Code Electrical Section Name 5617 Adimali 4609 Adoor 6516 Agali 6648 Alakode 6521 Alanellur 5501 Alappuzha ( North) 5502 Alappuzha (Town) 5503 Alappuzha(South) 6574 Alathiyoor 6509 Alathur 5568 Aluva North 5567 Aluva Town 5569 Aluva West 6534 Ambalappara 5505 Ambalappuzha 6762 Ambalavayal 4656 Amboori 5670 Ammadam 6756 Anakkayam 4597 Anchal 4669 Anchal (West) 6748 Angadipuram 5579 Angamaly. 5648 Annamanada 5553 Arakkunnam 5535 Aranmula 6789 Areekkad 6767 Areekkulam 6549 Areekode 5679 Arimboor 5705 Arookutty 5515 Aroor 5518 Arthinkal 4652 Aryanad 5572 Athani 4664 Athirampuzha 6615 Atholy 4531 Attingal. 4532 Avanavanchery. 4632 Ayarkunnam 4565 Ayathil. 6624 Ayenchery 4629 Aymanam 4591 Ayoor 4608 Ayroor 5678 Ayyanthole 6662 Azhikode 6743 Azhiyoor 6690 Badiadkka 6773 Balamthode 4542 Balaramapuram 6613 Balussery 6603 Beach 5699 Beach, Guruvayoor Page 1 of 13 SMS Format -> KSEB <Space> Section Code<Space> Consumer No -> 537252 4513 Beach, Trivandrum 6635 Beypore 5627 Bharananganam 6697 Bheemanady 5702 Big Bazar 6518 Bigbazar 6655 Burnassery 4558 Cantonment, Kollam 4506 Cantonment. 6602 Central, Kozhikode 4672 Chadayamangalam 6660 Chakkarakkal 6716 Chakkittapara 5651 Chalakudy 6538 Chalissery 6661 Chalode 5508 Champakulam 4636 Changanacherry 6585 Changaramkulam 6745 Chapparappadavu 5527 Charummood 4575 Chathannoor. 6772 Chattanchal 6708 Chattiparamba 5698 Chavakkad 4571 Chavara. 5691 Chelakkara 6744 Chelannur 6577 Chelari 6721 Chemperi 4644 -

Farm Guide 2018

FARM GUIDE 2018 Printed & Published by V. SUMA PRINCIPAL INFORMATION OFFICER FARM INFORMATION BUREAU Kowdiar P.O., Thiruvananthapuram - 695 003 Fax. 0471 - 2318186 e-mail : [email protected]/ [email protected] Compiled and Edited by B. Neena Asst. Director (Technical Asst. IT Division), Dept. of Agriculture Dr. Suja Mary Koshy Editor, Farm News, Dept. of Animal Husbandry Dr. Geetha Ram Information Officer, Dept. of Animal Husbandry Dr. P. Selvakumar Campaign Officer, Dept. of Animal Husbandry Anitha C.S. Agricultural Officer, Dept. of Agriculture Vishnu S.P. Agricultural Officer, Dept. of Agriculture Publication Officer Elizabeth George Asst. Director, Dairy Development Dept. Design & Layout Deepak Mouthatil Articles for Kerala Karshakan: [email protected] 0471- 2314358 Press Release: [email protected] 0471- 2317314 Farm News & General Communication: [email protected] 0471- 2318186 Website: www.fibkerala.gov.in Im¿jnI hnI-k\ I¿jIt£a hIp∏v ktµiw tIcfsaßpw lcnX{]Xo£IfpW¿Øn ]pXph¿jw ho≠pw kamKXamhpIbmWv. Im¿jnItIcfØn\v A`nam\apb¿Øp∂ t\´ßƒ ssIhcn®psIm≠v kwÿm\k¿°mcpw Im¿jnIhnIk\ I¿jIt£a hIp∏pw kZv`cWØns‚ ]mXbn¬ apt∂dpIbmWv. A[nImcta‰v c≠ph¿jw ]q¿Ønbm°p∂ Cu thfbn¬ tZiobXeØn¬Øs∂ {it≤bamb \nch[n I¿jIt£a Im¿jnI˛]cnÿnXnkulrZ ]≤XnIƒ s]mXpP\ ]¶mfnØ tØmsS \n¿hln°m≥Ign™p F∂Xn¬ Gsd NmcnXm¿Yyhpw A`nam\hpap≠v. tIcfØns‚ {][m\ Im¿jnIhnfIfmb s\√pw sXßpw C∂v kwÿm\k¿°m¿ ]≤XnIfneqsS Xncn®phchns‚ ]mXbnemWv. CXns‚ `mKambn k¿°m¿ {]Jym]n® s\¬h¿jmNcWØn\v anI® {]XnIcWhpw ]n¥pWbpamWv e`n®Xv. CXns\ ]n¥pS¿∂v 1193 Nnßw H∂papX¬ 1194 Nnßw H∂phsc tIch¿jambn BNcn®v IrjnhIp∏v hnhn[]≤XnIƒ \S∏nem°pIbmWv. -

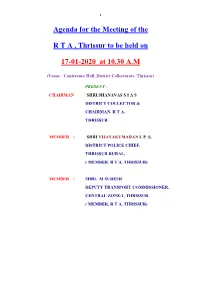

Agenda for the Meeting of the R T a , Thrissur to Be Held on 17-01-2020

1 Agenda for the Meeting of the R T A , Thrissur to be held on 17-01-2020 at 10.30 A.M (Venue : Conference Hall, District Collectorate, Thrissur) PRESENT : CHAIRMAN :SHRI.SHANAVAS S I A S DISTRICT COLLECTOR & CHAIRMAN, R T A, THRISSUR. MEMBER : :SHRI VIJAYAKUMARAN I. P. S, DISTRICT POLICE CHIEF, THRISSUR RURAL, ( MEMBER, R T A, THRISSUR) MEMBER : SHRI. M SURESH DEPUTY TRANSPORT COMMISSIONER, CENTRAL ZONE-1, THRISSUR. ( MEMBER, R T A, THRISSUR) 2 Item No 1 G-71138/2018 Agenda :. To Consider the application for the grant of fresh regular permit in respect of suitable stage carriage ( 28 seats in all ) to operate on the route Amballoor-Karikulamkadavu via Mannampetta- Pallikunnu-Varandarappilly-Pound-Veluppadam and Pulikanni- as Ordinary service Applicant:Sri. Nikhil Krishna,Thekkoodan House,Chembuchira P O,Thrissur Timings Karikulamkadavu Pulikanni Varandarappilly Amballoor A D A D A D A D 6.47 6.52 7.02 7.22 7.58 7.53 7.43 7.23 8.13 8.18 8.28 8.48 9.25 9.20 9.10 8.50 9.26 9.31 9.41 10.01 10.40 10.35 10.25 10.05 10.53 10.58 11.08 11.28 12.09 12.04 11.54 11.34 1.29 1.34 1.44 2.04 2.51 2.46 2.36 2.16 3.05 3.10 3.20 3.40 4.51 4.47 4.37 4.17 5.03 5.08 5.18 5.38 6.25 6.20 6.10 5.50 6.47 6.52 7.02 7.22 8.13 Halt 8.08 7.58 7.38 3 Total Route Length 14.1 KM Overlapping on the notified route – Nil Item No 2 G-89322/2019 Agenda :. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Thrissur Rural District from 10.05.2020To16.05.2020

Accused Persons arrested in Thrissur Rural district from 10.05.2020to16.05.2020 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 569/2020 U/s 188, 269 IPC, 118 (e) of KP Act 7&8 of VADANAP 10-05-2020 34, ALATHY HOUSE, NADUVILKK KG Act & 5 of PILLY SADIKK ALI BAILED BY 1 SUMESH MOHANAN at 00:50 Male NADUVILKARA ARA Kerala (Thrissur SI OF POLICE POLICE Hrs Epidemic Rural) Diseases Ordinance, 2020 569/2020 U/s 188, 269 IPC, 118 (e) of KP Act 7&8 of VADANAP PEZHI HOUSE, 10-05-2020 DHAMODH 39, NADUVILKK KG Act & 5 of PILLY SADIKK ALI BAILED BY 2 PREMAN NADUVILKARA,V at 00:50 ARAN Male ARA Kerala (Thrissur SI OF POLICE POLICE ATANAPPILLY Hrs Epidemic Rural) Diseases Ordinance, 2020 569/2020 U/s 188, 269 IPC, 118 (e) of KP MEPPARAMBIL Act 7&8 of VADANAP 10-05-2020 SURENDRA 40, HOUSE,PUTHUKU NADUVILKK KG Act & 5 of PILLY SADIKK ALI BAILED BY 3 BINESH at 00:50 N Male LANGARA,THALI ARA Kerala (Thrissur SI OF POLICE POLICE Hrs KULAM Epidemic Rural) Diseases Ordinance, 2020 569/2020 U/s 188, 269 IPC, 118 (e) of KP KODUVATHUPAR Act 7&8 of VADANAP 10-05-2020 43, AMBIL NADUVILKK KG Act & 5 of PILLY SADIKK ALI BAILED BY 4 PRADEEP KUMARAN at 00:50 Male HOUSE,NADUVIL ARA Kerala (Thrissur SI OF POLICE POLICE Hrs KARA Epidemic Rural) Diseases Ordinance, 2020 569/2020 U/s 188, 269 IPC, 118 (e) of KP Act 7&8 of VADANAP POKKAKKILLATH -

Thrissur District Office of the Department, Headed by Smt

DISTRICT SPATIAL PLAN THRISSUR DEPARTMENT OF TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING - GOVERNMENT OF KERALA January 2011 PREFACE Planning is a prerequisite for effective development. Development becomes comprehensive when growth centres are identified considering physical, social and economic variables of an area in an integrated manner. This indicates that planning of villages and towns are to be complementary. Second Administrative Reforms Commission (ARC) while interpreting the article 243 ZD of the Constitution of India states as follows. “This, in other words, means that the development needs of the rural and urban areas should be dealt with in an integrated manner and, therefore, the district plan, which is a plan for a large area consisting of villages and towns, should take into account such factors as ‘spatial planning’, sharing of ‘physical and natural resources’, integrated development of infrastructure’ and ‘environmental conservation’. All these are important, because the relationship between villages and towns is complementary. One needs the other. Many functions that the towns perform as seats of industry, trade and business and as providers of various services, including higher education, specialized health care services, communication etc have an impact on the development and welfare of rural people. Similarly, the orderly growth of the urban centre is dependent on the kind of organic linkage it establishes with its rural hinterland”. Therefore a move of harmonizing urban and rural centres of an area can be said as a move of planned urbanisation of the area. In this context, it is relevant to mention the 74th Amendment Act of the Constitution of India, which mandated the District Planning Committee to prepare a draft development plan for the district. -

Kodungallur Taluk Complete Loss of Buildings Sino

Kodungallur Taluk_Complete Loss of Buildings SINo. Localbody Type Localbody Name Ward No House No Sub No Taluk Name Village Name Owner Name Owner Address Damage Type Chazhu H, Painoor palla, Valapad 1 Grama Panchayat Edathiruthy 1 163 Kodungallur Edathiruthy Gopi C A (po), 680567 Complete loss of Buildings 2 Grama Panchayat Edathiruthy 1 188 Kodungallur Edathiruthy meenakshi amma kolathekkat house po valapad Complete loss of Buildings 3 Grama Panchayat Edathiruthy 1 359 A Kodungallur Edathiruthy Sreevidya p v Nambetty Complete loss of Buildings Kizhakkeppattu h, painoor 4 Grama Panchayat Edathiruthy 1 78 Kodungallur Edathiruthy Dasan K V kallumkadavu, valapad po, 680567 Complete loss of Buildings puthiyaveetil house kuttamangalam 5 Grama Panchayat Edathiruthy 2 211 Kodungallur Edathiruthy mohammed p.o.edathiruthy 680703 Complete loss of Buildings Ayinikkatt house kuttamangalam p.o. 6 Grama Panchayat Edathiruthy 2 220 Kodungallur Edathiruthy Velayudhan Edathiruthy Complete loss of Buildings thuppraden pradeep kutamangalam 7 Grama Panchayat Edathiruthy 2 225 Kodungallur Edathiruthy predeep thupradan po edathiruthy 680703 Complete loss of Buildings Puthirikkattu house Edathiruthy P O 8 Grama Panchayat Edathiruthy 2 226 A Kodungallur Edathiruthy Babu 680703 Complete loss of Buildings 9 Grama Panchayat Edathiruthy 2 346 Kodungallur Edathiruthy kunjayyappan Ayinikkatil house po edathiruthy Complete loss of Buildings kazhimbarath house 10 Grama Panchayat Edathiruthy 2 358 Kodungallur Edathiruthy Thanka kuttamangalam, Edathiruthy P O Complete -

Ground Water Information Booklet of Thrissur District, Kerala State

TECHNICAL REPORTS: SERIES ‘D’ CONSERVE WATER – SAVE LIFE भारत सरकार GOVERNMENT OF INDIA जल संसाधन मंत्रालय MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES कᴂ द्रीय भूजल बो셍 ड CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD केरल क्षेत्र KERALA REGION भूजल सूचना पुस्तिका, त्रिचूर स्ज쥍ला, केरल रा煍य GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET OF THRISSUR DISTRICT, KERALA STATE तत셁वनंतपुरम Thiruvananthapuram December 2013 1 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET OF THRISSUR DISTRICT, KERALA डॉ वी एस जोजी वैज्ञाननक ग Dr V.S. Joji Scientist C KERALA REGION BHUJAL BHAVAN KEDARAM, KESAVADASAPURAM NH-IV, FARIDABAD THIRUVANANTHAPURAM – 695 004 HARYANA- 121 001 TEL: 0471-2442175 TEL: 0129-12419075 FAX: 0471-2442191 FAX: 0129-2142524 GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET OF THRISSUR DISTRICT, KERALA STATE TABLE OF CONTENTS DISTRICT AT A GLANCE 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 1 2.0 RAINFALL AND CLIMATE ............................................................................................. 2 3.0 GEOMORPHOLOGY AND SOIL TYPES ........................................................................ 4 4.0 GROUND WATER SCENARIO ........................................................................................ 6 5.0 GROUND WATER MANAGEMENT STRATEGY ....................................................... 10 6.0 GROUND WATER RELATED ISSUES AND PROBLEMS ........................................ 11 7.0 AWARENESS AND TRAINING ACTIVITY ................................................................