DRAFT Helfand Letter Re Campanile Way 3-27-18

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

De Amerikaanse Reis Van Jan De Bie Leuveling Tjeenk in 1912

'European comes here for ideas' De Amerikaans Leuveline Bi e d n geJa rein sva Tjeenk in 1912 Kaspe Ommen rva n In zijn essay 'The Metho f Ariadnedo : tracin e Lineth g f o s cell een bezoek aan Amerika. Daar volgde een persoonlijke Influence between Some American Source theid an s r Dutch ontmoeting met Louis H. Sullivan (1856-1924), de leermees- Recipients'' vergelijk A.P . Leeuwen T t va . t speurenhe n naar ter van Purcell. Verder bezocht Berlage vele bouwwerken feiten en ontwikkelingen door de architectuurhistoricus met van ondermeer Sullivan, Henry H. Richardson (1838-1886) het volgen van de draad van Ariadne door Theseus in het la- en Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959).? byrin Knossosn e Amerikaans-Neder va t d geva n he n va lI . - Wright bezocht op zijn beurt rond 1910 het Europese con- landse wisselwerking, betoogt Van Leeuwen, is het van het tinent p uitnodiginO . e germanisd n va g n cultuurfilosooe t f grootste belang dat alle mogelijke lijnen gevolgd worden. Kuno Francke4 bracht hij een bezoek aan Duitsland. In Ber- Aan de reeds bestaande getuigenissen van Nederlandse archi- lijn werkte Wright op verzoek van de uitgever Ernst Was- n nieuwee u n tecteet ' Hofn bro s Berlagn ka nal fn Va n e muth aan de publikatie van een portfolio van zijn werk met toegevoegd worden. In een reisdagboek van de architect Jan de titel Ausgeführte Bouten und Entwürfe. Naast deze in- Leuveline Bi e d g Tjeenknieg no t t eerde openbaare da ,d n i r - vloedrijke publikatie vervulde Berlag n sleutelro- eee be t me 5 l heid gewees , wordis t n zeeee t r informatief beeld geschetst trekkin introductie d t t wer gto Wrighn he kva n eva Nedern i t - van de Amerikaanse architectuur in het begin van deze eeuw.2 'De werel' dom t behaleDireche n a zijn va tn ingenieursdiplome d n aa a Technische Hogeschoo Delfe t l t vertro e 27-jarigkd e d n Ja e Bie Leuveling Tjeenk (1885-1940) voor een reis om de we- reld. -

OTHER PRAIRIE SCHOOL ARCHITECTS George Washington

OTHER PRAIRIE SCHOOL ARCHITECTS George Washington Maher (1864–1926) Maher, at the age of 18, began working for the architectural firm of Bauer & Hill in Chicago before entering Silsbee’s office with Wright and Elmslie. Between late 1889 and early 1890, Maher formed a brief partnership with Charles Corwin. He then practiced independently until his son Philip joined him in the early 1920s. Maher developed his “motif-rhythm” design theory, which involved using a decorative symbol throughout a building. In Pleasant Home, the Farson-Mills House (Oak Park, 1897), he used a lion and a circle and tray motif. Maher enjoyed considerable social success, designing many houses on Chicago’s North Shore and several buildings for Northwestern University, including the gymnasium (1908–1909) and the Swift Hall of Engineering. In Winona, Minnesota, Maher designed the J. R. Watkins Administration Building (1911 – 1913), and the Winona Savings Bank (1913). Like Wright, Maher hoped to create an American style, but as his career progressed his designs became less original and relied more on past foreign styles. Maher’s frustration with his career may have led to his suicide in 1926. Dwight Heald Perkins (1867–1941) Perkins moved to Chicago from Memphis at age 12. He worked in the Stockyards and then in the architectural firm of Wheelock & Clay. A family friend financed sending Perkins to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he studied architecture for two years and then taught for a year. He returned to Chicago in 1888 after working briefly for Henry Hobson Richardson. Between 1888 and 1894 Perkins worked for Burnham & Root. -

John Galen Howard Collection, 1884-1931, (Bulk 1891-1927)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf1b69n5kh Online items available Inventory of the John Galen Howard Collection, 1884-1931, (bulk 1891-1927) Processed by Elizabeth Konzak; machine-readable finding aid created by Michael C. Conkin Environmental Design Archives College of Environmental Design 230 Wurster Hall #1820 University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-1820 Phone: (510) 642-5124 Fax: (510) 642-2824 Email: [email protected] http://www.ced.berkeley.edu/cedarchives/ © 2001 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Note Arts and Humanities--ArchitectureHistory--California History--Bay Area HistoryHistory--California HistoryGeographical (By Place)--CaliforniaGeographical (By Place)--California--Bay AreaHistory--University of California HistoryHistory--University of California History--UC Davis HistoryHistory--University of California History--UC Berkeley HistoryGeographical (By Place)--University of California--UC DavisGeographical (By Place)--University of California--UC Berkeley Inventory of the John Galen 1955-4 1 Howard Collection, 1884-1931, (bulk 1891-1927) Inventory of the John Galen Howard Collection, 1884-1931, (bulk 1891-1927) Collection number: 1955-4 Environmental Design Archives University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California Contact Information: Environmental Design Archives College of Environmental Design 230 Wurster Hall #1820 University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-1820 Phone: (510) 642-5124 Fax: (510) 642-2824 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.ced.berkeley.edu/cedarchives/ Processed by: Elizabeth Konzak Date Completed: March 2000 Encoded by: Michael C. Conkin © 2001 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: John Galen Howard Collection, Date (inclusive): 1884-1931, (bulk 1891-1927) Collection number: 1955-4 Creator: Howard, John Galen (1864-1931) Extent: 11 boxes, 20 flat file drawers, 13 tubes, 2 flat boxes, 5 folios Repository: Environmental Design Archives. -

John Galen Howard Papers, 1874-1954 (Bulk 1888-1931)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf2x0n99n1 Online items available Finding Aid the the John Galen Howard Papers, 1874-1954 (bulk 1888-1931) Processed by Elizabeth Konzak The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ © 2001 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid the the John Galen BANC MSS 67/35 c 1 Howard Papers, 1874-1954 (bulk 1888-1931) Finding Aid the the John Galen Howard Papers, 1874-1954 (bulk 1888-1931) Collection number: BANC MSS 67/35 c The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ Finding Aid Author(s): Processed by Elizabeth Konzak Finding Aid Encoded By: GenX © 2014 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Collection Title: John Galen Howard Papers Date (inclusive): 1874-1954 Date (bulk): 1888-1931 Collection Number: BANC MSS 67/35 c Extent: 21 boxes, 5 cartons, 1 volume, 4 oversize folders, 5 tubes2 digital objects (3 images) Repository: The Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ Languages Represented: Collection materials are in English Physical Location: For current information on the location of these materials, please consult the Library's online catalog. Access Collection is open for research, with the following exception: Panama-Pacific International Exposition drawings are RESTRICTED (Extremely fragile). -

Sixteen of Tfoe\$Everiteen Items Comprising This Multiple Resources Nomination Are Structures; One Item, Founders' Rock, Is a Natural Feature of the Campus

Check one Check one JL ©KCfsllent __ deteriorated X unaltered X original site JL gooft __ ruins -X altered __ moved date _ fair __ unexposed the present and original (if known) physical appearance Sixteen of tfoe\$everiteen items comprising this Multiple Resources Nomination are structures; one item, Founders' Rock, is a natural feature of the campus. The manmade structures are located on the central campus of the University of California (see appended maps). By their location, orientation toward major and mirldr axes, and Neo-Classic architectural style, they define the formal, turn-of-the-century concept of the University. Although a few of the structures have received exterior and interior alterations, their general architectural integrity is high. The items are divided into the following categories and described in sequence on the continuation pages. a. Individual Buildings or Structures 1) Hearst Greek Theatre, John Galen Howard, Architect; 1903 2) North Gate Hall, John Galen Howard, Architect; 1906 3) Hearst Memorial Mining Building, John Galen Howard, Architect; 1907 4) Sather Gate and Bridge, John Galen Howard, Architect; 1910 5) Hearst Gymnasium for Women, Bernard Maybeck and Julia Morgan, Architects; 1927 b. Buildings or Groups of Buildings and Their Landscaped Settings 1) Faculty Club a) (Men's) Faculty Club and Faculty Glade, Bernard Maybeck, Architect; 1902 2) Campanile Way and Esplanade a) Sather Tower (Campanile) and the Esplanade, John Galen Howard, Architect; 1914 b) South Hall, David Farquharson, Architect; 1873 c) Wheeler -

Sixteen of Tfoe\$Everiteen Items Comprising This Multiple Resources Nomination Are Structures; One Item, Founders' Rock, Is a Natural Feature of the Campus

Check one Check one JL ©KCfsllent __ deteriorated X unaltered X original site JL gooft __ ruins -X altered __ moved date _ fair __ unexposed the present and original (if known) physical appearance Sixteen of tfoe\$everiteen items comprising this Multiple Resources Nomination are structures; one item, Founders' Rock, is a natural feature of the campus. The manmade structures are located on the central campus of the University of California (see appended maps). By their location, orientation toward major and mirldr axes, and Neo-Classic architectural style, they define the formal, turn-of-the-century concept of the University. Although a few of the structures have received exterior and interior alterations, their general architectural integrity is high. The items are divided into the following categories and described in sequence on the continuation pages. a. Individual Buildings or Structures 1) Hearst Greek Theatre, John Galen Howard, Architect; 1903 2) North Gate Hall, John Galen Howard, Architect; 1906 3) Hearst Memorial Mining Building, John Galen Howard, Architect; 1907 4) Sather Gate and Bridge, John Galen Howard, Architect; 1910 5) Hearst Gymnasium for Women, Bernard Maybeck and Julia Morgan, Architects; 1927 b. Buildings or Groups of Buildings and Their Landscaped Settings 1) Faculty Club a) (Men's) Faculty Club and Faculty Glade, Bernard Maybeck, Architect; 1902 2) Campanile Way and Esplanade a) Sather Tower (Campanile) and the Esplanade, John Galen Howard, Architect; 1914 b) South Hall, David Farquharson, Architect; 1873 c) Wheeler -

COB Landmarks Updated April 2015

City of Berkeley Designated Landmarks Date of Number Street Name1 Name2 Construction Architect Designation Type DEMO Binder Number Note Joseph McVay Oceanview Sisterna 814 Addison Street House Historic District 1888 Roarke 3/1/2004 CBDist 267 Joseph and Wilson Oceanview Sisterna 816 Addison Street McVay House Historic District 1892 Unknown 3/1/2004 CBDist 267 Carrington House, Seth Babson & R. 1029 Addison Street Bartine 1893 Wenk 3/15/1982 SOM 54 1124 Addison Street John Brennan House 1891 Unknown 7/9/2001 LM 237 Cooper Woodworking Walter Crapo / Ben 1250 Addison Street Building 1912 Pearson 4/21/1986 LM 100 Saint Joseph the 1640 Addison Street Worker 0 Shea & Lofquist 3/18/1991 LM partial 160 Sanford G. Jackson / 1900 Addison Street Framat Lodge 1927 Sommarstrom Bros. 4/7/1997 LM 193 The John Boyd 1915 Addison Street House 1893 Unknown 1/5/2012 SOM 310 Golden Sheaf 2071 Addison Street Bakery 1905 Clinton Day 12/19/1977 LM 21 2110 Addison Street Underwood Building 1905 F.E. Armstrong 11/1/1993 SOM 178 Heywood Apartment 2119 Addison Street Bldg 1906 Unknown 4/7/2003 LM 251 Frederick H. Dakin Walter H. Ratcliff & 2750 Adeline Street Warehouse 1906 George T. Plowman 8/9/2004 LM 273 The Hoffman 2988 Adeline Street Building 1905 Henry Ahnefeld 7/6/2006 SOM 286 The William Clephane Corner 3027 Adeline Street Store 1905 C.M. Cook 9/7/2006 LM 290 William Wharff / C. 3228 Adeline Street Carlson's Block 1903 Ekman 7/19/1982 LM 64 3250 Adeline Street India Block 1903 A.W. -

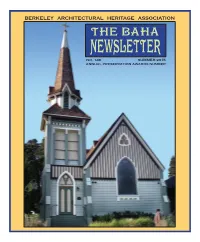

The Baha Newsletter No

BERKELEY ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE ASSOCIATION THE BAHA NEWSLETTER NO. 146 SUMMER 2015 ANNUAL PRESERVATION AWARDS NUMBER THE BAHA NEWSLETTER NO. 146 SUMMER 2015 Palace of Fine Arts C O N T E N T S Festival Hall Gifts to BAHA page 2 Elmwood House Tour—special to BAHA page 12 Message from the President page 3 Latest Landmark page 14 Preservation Award Winners page 5 Member News page 15 Walter W. Ratcliff, In Memoriam page 11 Fall Lecture Series page 16 Cover: Church of the Good Shepherd. John WEBSITES YOU SHOULD KNOW McBride, 2015 (Photoshop by Kathleen Burch). • BAHA’s website in- • BAHA maintains a • BAHA is on Top left: Bernard Maybeck’s Palace of Fine Arts cludes upcoming events, a blog where notices facebook: face- from a souvenir view book, 1915. list of Berkeley land- of immediate interest book.com/berke- Top right: Buffington family in front of Festival marks, illustrated essays, are posted: baha- ley.architectural. Hall, 1915. Both courtesy Anthony Bruce. and more: news.blogspot.com heritage?ref=hl berkeleyheritage.com BOARD OF DIRECTORS John McBride, President Sally Sachs, Thanks from BAHA Vice-President Candice Basham and Louise Hendry gave BAHA their copies of old house tour Carrie Olson, Corporate Secretary guides. From Richard B. Silver, a former owner of City of Berkeley Landmark, Jane McKinne-Mayer, Fox Court, came a gift of blueprints and original drawings (including a color ren- Recording Secretary dering) from the Fox Brothers office, and one of the original pieces of furniture Steven Finacom, Corresponding Secretary from the complex, a chair with a rawhide seat. -

2508 Ridge Road Landmark Application, Page 2 of 73

ATTACHMENT 2 LPC 02-04-16 Page 1 of 73 CITY OF BERKELEY Ordinance #4694 N.S. LANDMARK APPLICATION Bennington Apartments 2508 Ridge Road Berkeley, CA 94709 Figure 1. Bennington Apartments (photo: Daniella Thompson, Jan. 2016) ATTACHMENT 2 LPC 02-04-16 Page 2 of 73 1. Street Address: 2508 Ridge Road County: Alameda City: Berkeley ZIP: 94709 2. Assessor’s Parcel Number: 58-2200-13 (Daley’s Scenic Park, Block 11, portions of lots 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8) Dimensions: 119.5 ft x 60 ft + 50 ft x 40 ft.+ 29 ft x 50 ft (10,550 sq ft) Cross Streets: Euclid Avenue & Le Roy Avenue 3. Is property on the State Historic Resource Inventory? No Is property on the Berkeley Urban Conservation Survey? Yes Form #: 24210 4. Application for Landmark Includes: a. Building(s): Yes Garden: Front Yard Other Feature(s): b. Landscape or Open Space: Parapets, brick paving & trim c. Historic Site: No d. District: No e. Other: Entire Property 5. Historic Name: Bennington Apartments Commonly Known Name: N/A 6. Date of Construction: c. 1892; 1915 Factual: Yes Source of Information: Permit #4644, 8 June 1915; assessment records for 1893–1913 7. Architect: Unknown 8. Builder: Henry Investment Co. 9. Style: Early 1890s Shingle Style (front), Shingle/Stucco Arts & Crafts 10. Original Owner: Henry Investment Co. Original Use: Residential (6 apartments) 11. Present Owners: David C. Ruegg & Robert A. Ellsworth Rue-Ell Enterprises, Inc. 2437 Durant Ave, Berkeley, CA 94704 Present Occupant: Residential tenants 12. Present Use: Residential: Multiple (15 apartments in two buildings) Current Zoning: C-N(H) & R-3H Adjacent Property Zoning: C-N(H) & R-3H 13. -

California Memorial Stadium Executive Committee Records, 1920-1923

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt438nb01j No online items Guide to the California Memorial Stadium Executive Committee records, 1920-1923 Processed by The Bancroft Library staff University Archives. The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-2933 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.lib.berkeley.edu/BANC/UARC © 1999 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Guide to the California Memorial CU-291 1 Stadium Executive Committee records, 1920-1923 Guide to the California Memorial Stadium Executive Committee Records, 1920-1923 Collection number: CU-291 University Archives, The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California Contact Information: University Archives The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-2933 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.lib.berkeley.edu/BANC/UARC/ Processed by: The Bancroft Library staff © 1999 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Collection Title: California Memorial Stadium Executive Committee Records, Date (inclusive): 1920-1923 Collection Number: CU-291 Creator: California Memorial Stadium Executive Committee (Berkeley, Calif.) Extent: 2 boxes Repository: The Bancroft Library. University Archives. Berkeley, California 94720-6000 Physical Location: For current information on the location of these materials, please consult the Library's online catalog. Languages Represented: English Access Collection is open for research. Publication Rights Copyright has not been assigned to The Bancroft Library. All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the Head of Public Services. -

John Galen Howard Pictorial Collection, 1885-1920

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf038n97h4 No online items Finding Aid to the John Galen Howard Pictorial Collection, 1885-1920 Processed by Elizabeth Konzak Funding for revision of arrangement and description of this collection was provided by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. The Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu © 2001 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid to the John Galen BANC PIC 1967.016-1967.018 1 Howard Pictorial Collection, 1885-1920 Finding Aid to the John Galen Howard Pictorial Collection, 1885-1920 Collection number: BANC PIC 1967.016-1967.018 Funding for arrangement and description of this collection was provided by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California Contact Information: The Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu Processed by: Elizabeth Konzak Date Completed: October 2000 Encoded by: Michael C. Conkin; revised by Jeanne Gahagan © 2001 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Collection Title: John Galen Howard Pictorial Collection Date (inclusive): 1885-1920 Collection Number: BANC PIC 1967.016-1967.018 Creator: Howard, John Galen, 1864-1931 Extent: circa 235 photographic prints, circa 65 drawings, 10 negatives and 1 Sketchbook. Repository: The Bancroft Library. Berkeley, California 94720-6000 Abstract: The John Galen Howard Pictorial Collection contains personal papers, including photographs and sketches of Howard and his wife, Mary Robertson Bradbury; and project records, including photographs from various commercial, religious, educational, and residential projects in California, Washington, New York and Massachusetts. -

Greek Theatre

Historic Structure Report The Hearst Greek Theatre University of California Berkeley, California Prepared by Frederic Knapp Architect, Inc. San Francisco, California April 2007 It is Greece! -Sarah Bernhardt Historic Structure Report Greek Theatre University of California Table of Contents I. Historic Structure Report A. Executive Summary................................................................1 B. Introduction............................................................................4 C. Site and Building History ........................................................9 D. Theater in Antiquity ...............................................................24 E. Late History: Planning and Construction ................................30 F. Description..............................................................................41 G. Selected Architectural Elements ..............................................57 H. Site..........................................................................................61 I. Utilities and Infrastructure......................................................69 J. Alterations and Use .................................................................71 Construction Chronology ........................................................80 K. Use of the Greek Theatre .........................................................85 L. Significance and Integrity Evaluation .....................................90 M. Ratings of Significance ............................................................96 N. Architectural