Bilingualism and Intergroup Relationship in Tribal and Non-Tribal Contact Situations Ajit K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

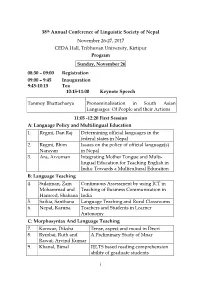

38Th Annual Conference of Linguistic Society of Nepal

38th Annual Conference of Linguistic Society of Nepal November 26-27, 2017 CEDA Hall, Tribhuvan University, Kirtipur Program Sunday, November 26 08:30 – 09:00 Registration 09:00 – 9:45 Inauguration 9:45-10:15 Tea 10:15-11:00 Keynote Speech Tanmoy Bhattacharya Pronominalisation in South Asian Languages: Of People and their Actions 11:05 -12:20 First Session A: Language Policy and Multilingual Education 1. Regmi, Dan Raj Determining official languages in the federal states in Nepal 2. Regmi, Bhim Issues on the policy of official language(s) Narayan in Nepal 3. Ara, Arzuman Integrating Mother Tongue and Multi- lingual Education for Teaching English in India: Towards a Multicultural Education B: Language Teaching 4. Sulaiman, Zain Continuous Assessment by using ICT in Mohammad and Teaching of Business Communication in Hameed, Shabana India 5. Saikia, Santhana Language Teaching and Rural Classrooms 6. Nepal, Karuna Teachers and Students in Learner Autonomy C: Morphosyntax And Language Teaching 7. Konwar, Diksha Tense, aspect and mood in Deori 8. Rymbai, Ruth and A Preliminary Study of Mnar Rawat, Arvind Kumar 9. Khanal, Bimal IELTS based reading comprehension ability of graduate students i 12:25 -13:15 Second Session A: Thematic discussion on official language(s) in Nepal (Nepali medium session conducted by Language Commission B: Sociolinguistics 10. Tiwari, Nabin Role of media in power and politics 11. Mandal, Monalisha Copulation And Inhumanity In and Rahman, Mojibur Benjamin Kwakye's The Sun by Night: A Study in Pragmatic Discourse C: Discourse Analysis 12. Mahato, Shatya Kumar English in Nepal: Discourse Features 13. Tigga, Richa Power and Discourse analysis in Emma Donoghue's novel 'Room' 13:15 – 14:00 Lunch 14:00 - 16:05 Third Session A: Sociolinguistics 14. -

India As a Lingustic Area Author(S): M. B. Emeneau Source: Language, Vol

India as a Lingustic Area Author(s): M. B. Emeneau Source: Language, Vol. 32, No. 1, (Jan. - Mar., 1956), pp. 3-16 Published by: Linguistic Society of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/410649 Accessed: 10/05/2008 10:03 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=lsa. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We enable the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org INDIA AS A LINGUISTIC AREA M. B. EMENEAU University of California, Berkeley The American anthropologists who have been linguistic scholars as well- I would mention Boas, Sapir, and, last but not least, Alfred L. -

Unit 2 Distribution of Indian Tribes, Groups and Sub-Groups: Causes of Variations

Tribal Cosmogenies UNIT 2 DISTRIBUTION OF INDIAN TRIBES, GROUPS AND SUB-GROUPS: CAUSES OF VARIATIONS Structure 2.0 Objectives 2.1 Introduction 2.2 Distribution of Indian tribes: groups and sub-groups 2.2.1 Geographical 2.2.2 Linguistic 2.2.3 Racial 2.2.4 Size 2.2.5 Economy or subsistence pattern 2.2.6 Degree of incorporation into the Hindu society 2.3 Causes of variations 2.3.1 Migration 2.3.2 Acculturation and assimilation. 2.3.3 Geography or the physical environment 2.4 Let us sum up 2.5 Activity 2.6 References and further reading 2.7 Glossary 2.8 Answers to questions 2.0 OBJECTIVES After having read this Unit, you will be able to: x get a panoramic view of the Indian tribes; x understand the principles upon which their classification is based; and x map their distribution on the basis of their geographical location, language, physical attributes, economy and social structure. 2.1 INTRODUCTION We have had a general outline about the tribes of India in the preceding Unit (Course 4-Block 1- Unit 1). In this present Unit we will deal with distribution of the tribes of India in detail. Structurally this Unit is divided into two main sections. In this first section of the Unit we will discuss the distribution pattern of Indian tribes and how they are classified into different groups and sub-groups based on various criteria. 24 These criteria are based on their geographical location, language, physical Migrant Tribes / Nomads attributes, economy and the degree of incorporation into the Hindu society. -

An Introduction to the Grammar of the Kui Or Kandh Language

; AN INTRODUCTION TO THE Grammar of the Kui or Kandh Language. BY LINGUM LETCHMAJEE, lATB DEPUTY TRANSLATOR, QAHJAM AGENT'8 OFFICE. SECOND EDITION. Eevised and Corrected, C^alcutta BENGAL SECRETAEIAT PEESS. 1902. [^Frice— Indic^n], •jcf,i, ' i;' Ekdluh, Is, 6d.'] / Or :ARP£WTJEfi ^ <^' Published at the Benqai. Secretariat Book Dep6t, Writers' Buildings, Calcutta. In India — Messrs. Thackeb, Spink & Co., Calcutta and Simla. Messrs. Newman & Co., Calcutta. Messrs. Higoinbotham & Co., Madras. Messrs. Tii acker & Co., Ld., Bombay. Messrs. A. J. Combridge & Co., Bombay. Mb. E. Seymour Hale, 53 Esplanade Road, Fort, Bombay, and Calcutta. Th3 Superintendent, American Baptist Mission Press, Rangoon. Messrs. S. K. Lahiri & Co., Printers and Book-sellers, College Street, Calcutta. Rai Sahib M. Gulab Singh & Sons, Proprie- tors of the Mufid-i-am Press, Lahore, Punjab. Messrs. V. Kalyanarama Iybr & Co., Book-sellers, &c., Madras. Messrs. D. B. Taraporevala, Sons & Co., Book-sellers, Bombay. In England— Mr. E. a. Arnold, 37 Bedford Street, Strand, London. Messrs. Constable tt-Co., 2 Whitehall Gardens, London. Messrs. Sampson Low, Marston & Co., St. Dunstan's House, Fetter Lane, London. Messrs. Luzac & Co., 46 Great Russell Street, London. Messrs. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubnek & Co., Charing Cross Road, London. Mr. B. Alfred Quaritch, 15 Piccadilly, London. Messrs. P. S. I\jng & Son, 2 & 4 Great Smith Street, Westminster, London. Messrs. H. S. King & Co., 65 Cornhill, London, Messrs. Williams and Norgatb, Oxford. Messrs. Deighton Bell & Co., Cambridge. On the Continent— Messrs. R. Friedlander & Sohn, Berlin, N. W. Carlstrasse, 11. ItlR. Otto Harbasso'smtz, Leipzig. Mr. Karl Hiersemann, Leipzig. litR. Ernest Leroux, 28 Rue Bonaparte, Paris, Mb. -

Centre for Preservation of Endangered Dravidian Languages

National Workshop on Standardisation of IT Enabled Transliteration, Glossing and Meta-language for Dravidian Languages Draft of the Standards of IT enabled Transliteration, Glossing and Meta-language for Dravidian Languages circulated in advance among the participants of the workshop, 6-10 March 2017 Organised by CPeDL CCCentre for PPPreservation of EEEndangered DDDravidian LLLanguages Funded by University Grants Commission Dept. of Dravidian & Computational Linguistics Dravidian University, Kuppam AP Content 1. Introduction 2. Resource Persons 3. Schedule 4. General Guidelines 5. Proposed standards 6.1. Transliteration 1. Tamil 14. Kuvi 2. Malayalam 15. Pengo 3. Kannada 16. Manda 4. Kodagu 17. Kolami 5. Toda 18. Naiki 6. Kota 19. Naikiri 7. Irula 20. Parji 8. Tulu 21. Ollari 9. Telugu 22. Gadaba 10. Gondi 23. Kurux/Oraon 11. Koya 24. Malto 12. Konada 25. Brahui 13. Kui 6.2. Abbreviations of grammatical categories 6.3. Glossing 6.5. Technology issues 7. Supporting materials 8. Appendixes Organisers Dr. M. C. Kesava Murty Assistant Professor, Deputy Coordinator SAP-DRS Coordinator of the workshop P. Sreekumar Assistant Professor, Deputy Director of CPEDL Deputy Coordinator of the workshop Prof. G. Balasubramanian Rector, Dravidian University; Director of CPeDL & Coordinator of SAP-DRS Dr. Ganeshan Ambedkar Associate Professor, Head of the Department Dr. M. Prasad Naik Assistant Professor Draft compiled by Mr. Bharath Kumar M S (Research Scholar) Mr. M Rajakrishna (Research Scholar) Mr. K. Suryanarayana (Research Scholar) Mr. D Raja Rao (Research Scholar) 1. Introduction: Linguistic studies are much advanced scientific practice today. Linguistic literature is addressing global linguistic community irrespective of the paradigm, family and the size of the languages. -

LCSH Section I

I(f) inhibitors I-270 (Ill. and Mo. : Proposed) I Ho Yüan (Peking, China) USE If inhibitors USE Interstate 255 (Ill. and Mo.) USE Yihe Yuan (Beijing, China) I & M Canal National Heritage Corridor (Ill.) I-270 (Md.) I-hsing ware USE Illinois and Michigan Canal National Heritage USE Interstate 270 (Md.) USE Yixing ware Corridor (Ill.) I-278 (N.J. and N.Y.) I-Kiribati (May Subd Geog) I & M Canal State Trail (Ill.) USE Interstate 278 (N.J. and N.Y.) UF Gilbertese USE Illinois and Michigan Canal State Trail (Ill.) I-394 (Minn.) BT Ethnology—Kiribati I-5 USE Interstate 394 (Minn.) I-Kiribati language USE Interstate 5 I-395 (Baltimore, Md.) USE Gilbertese language I-10 USE Interstate 395 (Baltimore, Md.) I kuan tao (Cult) USE Interstate 10 I-405 (Wash.) USE Yi guan dao (Cult) I-15 USE Interstate 405 (Wash.) I language USE Interstate 15 I-470 (Ohio and W. Va.) USE Yi language I-15 (Fighter plane) USE Interstate 470 (Ohio and W. Va.) I-li Ho (China and Kazakhstan) USE Polikarpov I-15 (Fighter plane) I-476 (Pa.) USE Ili River (China and Kazakhstan) I-16 (Fighter plane) USE Blue Route (Pa.) I-li-mi (China) USE Polikarpov I-16 (Fighter plane) I-478 (New York, N.Y.) USE Taipa Island (China) I-17 USE Westway (New York, N.Y.) I-liu District (China) USE Interstate 17 I-495 (Mass.) USE Yiliu (Guangdong Sheng, China : Region) I-19 (Ariz.) USE Interstate 495 (Mass.) I-liu Region (China) USE Interstate 19 (Ariz.) I-495 (Md. -

A Comparative Study of Odia and Kui Morphology Impact Factor: 5.2 IJAR 2016; 2(9): 23-29 Received: 06-07-2016 Dr

International Journal of Applied Research 2016; 2(9): 23-29 ISSN Print: 2394-7500 ISSN Online: 2394-5869 A comparative study of Odia and Kui morphology Impact Factor: 5.2 IJAR 2016; 2(9): 23-29 www.allresearchjournal.com Received: 06-07-2016 Dr. Govinda Chandra Penthoi Accepted: 07-08-2016 Abstract Dr. Govinda Chandra Penthoi Morphology deals with the structure of words. The basic unit is the focus of study in morphology is Research Scholar, Dept. of morpheme. The formal variants of a morpheme are called allomorphs of that morpheme. The variant Linguistics, Berhampur may be phonologically or morphologically conditioned. A morpheme may be a free or a bound form. University, Bhanjabihar, Alternatively we can say that a word consist of one or more than one morpheme. From the point of Berhampur, Ganjam, Odisha view of its internal structure, a word may consist of (i) a root morpheme only (ii) a root and one or more non root morpheme or (iii) more than one root morpheme. The non root morphemes are bound forms and are generally referred to as affixes. Roots enter into further morphological constructions and form a base while non-roots do not. The objective of this study is to compare morphological analysis or word formation of Odia and Kui language. The approach is data oriented and uses in general. The structuralist methodology has been followed for the analysis of the data in the present work. Data was collected from the native speakers through field visit to various Kui speaking areas. Keywords: Morphology, morpheme, root, free and bound morpheme, inflection, derived, compounding, reduplication, echo formation, contraction Introduction Odisha is a land of many languages. -

GOO-80-02119 392P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 228 863 FL 013 634 AUTHOR Hatfield, Deborah H.; And Others TITLE A Survey of Materials for the Study of theUncommonly Taught Languages: Supplement, 1976-1981. INSTITUTION Center for Applied Linguistics, Washington, D.C. SPONS AGENCY Department of Education, Washington, D.C.Div. of International Education. PUB DATE Jul 82 CONTRACT GOO-79-03415; GOO-80-02119 NOTE 392p.; For related documents, see ED 130 537-538, ED 132 833-835, ED 132 860, and ED 166 949-950. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC16 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Dictionaries; *InStructional Materials; Postsecondary Edtmation; *Second Language Instruction; Textbooks; *Uncommonly Taught Languages ABSTRACT This annotated bibliography is a supplement tothe previous survey published in 1976. It coverslanguages and language groups in the following divisions:(1) Western Europe/Pidgins and Creoles (European-based); (2) Eastern Europeand the Soviet Union; (3) the Middle East and North Africa; (4) SouthAsia;(5) Eastern Asia; (6) Sub-Saharan Africa; (7) SoutheastAsia and the Pacific; and (8) North, Central, and South Anerica. The primaryemphasis of the bibliography is on materials for the use of theadult learner whose native language is English. Under each languageheading, the items are arranged as follows:teaching materials, readers, grammars, and dictionaries. The annotations are descriptive.Whenever possible, each entry contains standardbibliographical information, including notations about reprints and accompanyingtapes/records -

A Linguistic Study on Consonant Phonology of Kui Language

IMPACT: International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Literature (IMPACT: IJRHAL) ISSN(P): 2347-4564; ISSN(E): 2321-8878 Vol. 4, Issue 7, Jul 2016, 23-38 © Impact Journals A LINGUISTIC STUDY ON CONSONANT PHONOLOGY OF KUI LANGUAGE GOVINDA CHANDRA PENTHOI Guest Faculty, Department of Linguistics, Berhampur University, Bihar, Odisha, India ABSTRACT Kui (ISO639-3 Code ‘Kxu’) is a language spoken by Kondh or Kondha (/K ɔndh ɔ/) tribe. Majority of the Kui- speaking Kondhs live in the hilly and forested areas of South and central Odisha especially in the undivided districts of Kondhamal, Koraput and Kalahandi. The other language spoken by Kondhs is Kuvi which is very similar to Kui. Kondh people being an underdeveloped tribal people, study of their language, society and culture draws a lot of attention of academics, administration and other philanthropic agencies. The objective of this study is to present the consonant sound and phonology of Kui language. The approach is data oriented and uses in general. The structuralist methodology has been followed for the analysis of the data in the present work. Data was collected from the native speakers through field visit to various Kui speaking areas. KEYWORDS : ‘Kui, Consonant Sound, Central Dravidian, Segmental Sound, Stop, Nasal, Lateral, Flap, Fricative, Voiceless, Voiced, Aspirated, Affricate INTRODUCTION Odisha is a land of many languages. Languages belonging to three distinct language families are spoken in this state. Apart from Odia, the major languages, around 46 tribal languages are spoken in Odisha. Many of the speakers know more than one language. According to the 2001 census the total population of Odisha is 36804660. -

Vowel Harmony in Kui

IRA-International Journal of Education & Multidisciplinary Studies ISSN 2455–2526; Vol.04, Issue 01 (2016) Institute of Research Advances http://research-advances.org/index.php/IJEMS Vowel Harmony in Kui Dr. Govinda Chandra Penthoi Guest Faculty, Dept. of Linguistics Berhampur University Bhanjabihar- 760007, India. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21013/jems.v4.n1.p21 How to cite this paper: Penthoi, G. (2016). Vowel Harmony in Kui. IRA International Journal of Education and Multidisciplinary Studies (ISSN 2455–2526), 4(1). doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.21013/jems.v4.n1.p21 © Institute of Research Advances This works is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International License subject to proper citation to the publication source of the work. Disclaimer: The scholarly papers as reviewed and published by the Institute of Research Advances (IRA) are the views and opinions of their respective authors and are not the views or opinions of the IRA. The IRA disclaims of any harm or loss caused due to the published content to any party. 177 IRA-International Journal of Education & Multidisciplinary Studies ABSTRACT Kui (ISO639-3 Code ‘Kxu’) is a language spoken by Kondh or Kondha (/Kɔndhɔ/) tribe. Majority of the Kui-speaking Kondhs live in the hilly and forested areas of South and central Odisha especially in the undivided districts of Kondhamal, Koraput and Kalahandi. The other language spoken by Kondhs is Kuvi which is very similar to Kui. Kondh people being an underdeveloped tribal people, study of their language, society and culture draws a lot of attention of academics, administration and other philanthropic agencies. -

A Grammar of the Kui Language

Jk. GEAMMAE OF THE KUI LANGUAGE. BY J. E. jFRIEND-PEREIRA, b.a., OF THE PROVINCIAL CIVIL SERVICE, BENGAL. FIRST EDITION, Calcutta: BENGAL SECRETARIAT BOOK DEPOT. 1909. 2fe. 2-12 [Price Indian, ; English, ,j CARPHT1 Published at the Bengal Secretariat Book Depot, Writers' Buildings, Calcutta. In India Messrs. Thacker, Spink & Co., Calcutta and Simla. Messrs. Newman & Co., Calcutta. Messrs. Higginbotham & Co., Madras. Messrs. Thacker & Co., Ld., Bombay. MESSRS. A. J. Combridge & Co., Bombay. The Superintendent, American Baptist Mission Press, Rangoon. Mrs. Radhabai Atmaram Saqoon, Bombay. Messrs. R. Cambray & Co., Calcutta. Rai Sahib M. Gulab Singh & Sons, Proprietors of the Mufid-i-am Press, Lahore, Punjab. Messrs. Thompson k Co., Madras. Messrs. S. Mdrthy & Co., Madras. Messrs. Gopal Narayen & Co., Bombay. Messrs. B. Banerjee k Co., 25 Comwallis Street, Calcutta. Messrs. S. K. Lahiri k Co., Printers and Book-sellers, College Street, Calcutta. Messrs. V. Kalyanarama Iyer & Co., Book- sellers, &c, Madras. Messrs. D. B. Taraporevala, Sons k Co., Book-sellers, Bombay. MESSRS. G. A. Nateson & Co., Madras. Mr. N. B. Mathur, Superintendent, Nazir Kanum Hind Press, Allahabad. The Calcutta School-Book Society. Mr. Sunder Pandurang, Bombay. Messrs. A. M. and J. Ferguson Ceylon. Messrs. Temple & Co., Madras. Messrs. Combridge & Co., Madras. Messrs. A. R. Pillai k Co., Trivandrum Messrs. A. Chand & Co., Punjab. Babu S. C. Talukdar, Proprietor, Students & Co., Cooch Behar. In England Mr. E. A. Arnold, 41 k 43 Maddox Street, Bond Street, London, W. Messrs. Constable k Co., 10 Orange Street, Leicester Square, London, W. C. Messrs. Grindlay k Co., 54 Parliament Street, London, S. W. Messrs. -

Negation in Dravidian Languages

Negation in Dravidian languages A descriptive typological study on verbal and non-verbal negation in simple declarative sentences Camilla Lindblom Department of Linguistics Magister Thesis 15 ECTS credits General Linguistics Spring term 2014 Supervisor: Ljuba Veselinova Examiner: Henrik Liljegren Reviewer: Bernhard Wälchli Negation in Dravidian languages A descriptive typological study on verbal and non-verbal negation in simple declarative sentences Camilla Lindblom Abstract Over the years the typology of negation has been much described and discussed. However, focus has mainly been on standard negation. Studies on non-verbal negation in general and comparative studies covering the complete domain of non-verbal negation in particular are less common. The strategies to express non-verbal negation vary among languages. In some languages the negation strategy employed in standard negation is also used in non-verbal negation. Several researchers have argued that languages express negation of non-verbal predications using special constructions. This study examines and describes negation strategies in simple declarative sentences in 18 Dravidian languages. The results suggest that the majority of the Dravidian languages included in this study express standard negation by the use of a negative suffix while non-verbal negation is expressed by a negative verb. Further distinctions are made in the negation of non-verbal predications in that different negation markers are used for attributive and existential/possessive predications respectively. Keywords Typology, non-verbal negation, Dravidian languages Sammanfattning Negationens typologi har under de gångna åren varit föremål för en omfattande beskrivning och debatt. Trots detta har fokus huvudsakligen varit på standardnegation. Studier av icke-verbal negation i allmänhet och komparativa studier av domänen icke-verbal negation i synnerhet hör till ovanligheterna.