Lunar Observing Report February 12Th 2011- Lichfield - 66% Waxing Gibbous

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lunar Impact Crater Identification and Age Estimation with Chang’E

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-20215-y OPEN Lunar impact crater identification and age estimation with Chang’E data by deep and transfer learning ✉ Chen Yang 1,2 , Haishi Zhao 3, Lorenzo Bruzzone4, Jon Atli Benediktsson 5, Yanchun Liang3, Bin Liu 2, ✉ ✉ Xingguo Zeng 2, Renchu Guan 3 , Chunlai Li 2 & Ziyuan Ouyang1,2 1234567890():,; Impact craters, which can be considered the lunar equivalent of fossils, are the most dominant lunar surface features and record the history of the Solar System. We address the problem of automatic crater detection and age estimation. From initially small numbers of recognized craters and dated craters, i.e., 7895 and 1411, respectively, we progressively identify new craters and estimate their ages with Chang’E data and stratigraphic information by transfer learning using deep neural networks. This results in the identification of 109,956 new craters, which is more than a dozen times greater than the initial number of recognized craters. The formation systems of 18,996 newly detected craters larger than 8 km are esti- mated. Here, a new lunar crater database for the mid- and low-latitude regions of the Moon is derived and distributed to the planetary community together with the related data analysis. 1 College of Earth Sciences, Jilin University, 130061 Changchun, China. 2 Key Laboratory of Lunar and Deep Space Exploration, National Astronomical Observatories, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 100101 Beijing, China. 3 Key Laboratory of Symbol Computation and Knowledge Engineering of Ministry of Education, College of Computer Science and Technology, Jilin University, 130012 Changchun, China. 4 Department of Information Engineering and Computer ✉ Science, University of Trento, I-38122 Trento, Italy. -

Glossary Glossary

Glossary Glossary Albedo A measure of an object’s reflectivity. A pure white reflecting surface has an albedo of 1.0 (100%). A pitch-black, nonreflecting surface has an albedo of 0.0. The Moon is a fairly dark object with a combined albedo of 0.07 (reflecting 7% of the sunlight that falls upon it). The albedo range of the lunar maria is between 0.05 and 0.08. The brighter highlands have an albedo range from 0.09 to 0.15. Anorthosite Rocks rich in the mineral feldspar, making up much of the Moon’s bright highland regions. Aperture The diameter of a telescope’s objective lens or primary mirror. Apogee The point in the Moon’s orbit where it is furthest from the Earth. At apogee, the Moon can reach a maximum distance of 406,700 km from the Earth. Apollo The manned lunar program of the United States. Between July 1969 and December 1972, six Apollo missions landed on the Moon, allowing a total of 12 astronauts to explore its surface. Asteroid A minor planet. A large solid body of rock in orbit around the Sun. Banded crater A crater that displays dusky linear tracts on its inner walls and/or floor. 250 Basalt A dark, fine-grained volcanic rock, low in silicon, with a low viscosity. Basaltic material fills many of the Moon’s major basins, especially on the near side. Glossary Basin A very large circular impact structure (usually comprising multiple concentric rings) that usually displays some degree of flooding with lava. The largest and most conspicuous lava- flooded basins on the Moon are found on the near side, and most are filled to their outer edges with mare basalts. -

Mode of Emplacement of Lunar Mare Volcanic Deposits: Graben Formation Due to Near Surface Deformation Accompanying Dike Emplacement at Rima Parry V; J

LPSC XXIV 62 1 MODE OF EMPLACEMENT OF LUNAR MARE VOLCANIC DEPOSITS: GRABEN FORMATION DUE TO NEAR SURFACE DEFORMATION ACCOMPANYING DIKE EMPLACEMENT AT RIMA PARRY V; J. W. Head1 and L. Wil~onl-~.Dept. Geol. Sci., Brown Univ., Providence, RI 02912 USA, Environ. Sci. Div., Inst. of Environ. and Biol. Sci., Lancaster Univ., Lancaster LA1 4YQ, UK. Abstract: Theoretical analyses, together with the observed style of emplacement of lunar mare volcanic deposits, strongly suggest that mare volcanic eruptions are fed by dikes from source regions at the base of the crust or deeper in the lunar mantle (1). Some dikes intrude into the lower crust, while others penetrate to the surface and are the sources for voluminous outpourings of lava. Still others stall near the surface generating a near-surface extensional stress field. We have investigated the hypothesis that some lunar linear rilles (graben) are the near- surface manifestations of dikes intruded to shallow depths. For a specifTc example (Runa Parry V) we show that the geometry of the faults implies a mean dike width of about 150 m and depth to the dike top of about 500 m, values consistent with other theoretical and observational data on lunar dike geometry. Localized pplastic deposits along Rima Pany V are evidence for the presence of near-surface magma, and are interpreted to be the result of degassing and pyroclastic eruption subsequent to the emplacement of the dike. Dike Emplacement in the Lunar Crust: Linear and arcuate rilles (simple graben) have been interpreted to be linked to impact basin structure, and to the emplacement of mare deposits in the basins via flexural deformation related to the mare deposit load (2). -

Relative Ages

CONTENTS Page Introduction ...................................................... 123 Stratigraphic nomenclature ........................................ 123 Superpositions ................................................... 125 Mare-crater relations .......................................... 125 Crater-crater relations .......................................... 127 Basin-crater relations .......................................... 127 Mapping conventions .......................................... 127 Crater dating .................................................... 129 General principles ............................................. 129 Size-frequency relations ........................................ 129 Morphology of large craters .................................... 129 Morphology of small craters, by Newell J. Fask .................. 131 D, method .................................................... 133 Summary ........................................................ 133 table 7.1). The first three of these sequences, which are older than INTRODUCTION the visible mare materials, are also dominated internally by the The goals of both terrestrial and lunar stratigraphy are to inte- deposits of basins. The fourth (youngest) sequence consists of mare grate geologic units into a stratigraphic column applicable over the and crater materials. This chapter explains the general methods of whole planet and to calibrate this column with absolute ages. The stratigraphic analysis that are employed in the next six chapters first step in reconstructing -

DMAAC – February 1973

LUNAR TOPOGRAPHIC ORTHOPHOTOMAP (LTO) AND LUNAR ORTHOPHOTMAP (LO) SERIES (Published by DMATC) Lunar Topographic Orthophotmaps and Lunar Orthophotomaps Scale: 1:250,000 Projection: Transverse Mercator Sheet Size: 25.5”x 26.5” The Lunar Topographic Orthophotmaps and Lunar Orthophotomaps Series are the first comprehensive and continuous mapping to be accomplished from Apollo Mission 15-17 mapping photographs. This series is also the first major effort to apply recent advances in orthophotography to lunar mapping. Presently developed maps of this series were designed to support initial lunar scientific investigations primarily employing results of Apollo Mission 15-17 data. Individual maps of this series cover 4 degrees of lunar latitude and 5 degrees of lunar longitude consisting of 1/16 of the area of a 1:1,000,000 scale Lunar Astronautical Chart (LAC) (Section 4.2.1). Their apha-numeric identification (example – LTO38B1) consists of the designator LTO for topographic orthophoto editions or LO for orthophoto editions followed by the LAC number in which they fall, followed by an A, B, C or D designator defining the pertinent LAC quadrant and a 1, 2, 3, or 4 designator defining the specific sub-quadrant actually covered. The following designation (250) identifies the sheets as being at 1:250,000 scale. The LTO editions display 100-meter contours, 50-meter supplemental contours and spot elevations in a red overprint to the base, which is lithographed in black and white. LO editions are identical except that all relief information is omitted and selenographic graticule is restricted to border ticks, presenting an umencumbered view of lunar features imaged by the photographic base. -

July 2020 in This Issue Online Readers, ALPO Conference November 6-7, 2020 2 Lunar Calendar July 2020 3 Click on Images an Invitation to Join ALPO 3 for Hyperlinks

A publication of the Lunar Section of ALPO Edited by David Teske: [email protected] 2162 Enon Road, Louisville, Mississippi, USA Recent back issues: http://moon.scopesandscapes.com/tlo_back.html July 2020 In This Issue Online readers, ALPO Conference November 6-7, 2020 2 Lunar Calendar July 2020 3 click on images An Invitation to Join ALPO 3 for hyperlinks. Observations Received 4 By the Numbers 7 Submission Through the ALPO Image Achieve 4 When Submitting Observations to the ALPO Lunar Section 9 Call For Observations Focus-On 9 Focus-On Announcement 10 2020 ALPO The Walter H. Haas Observer’s Award 11 Sirsalis T, R. Hays, Jr. 12 Long Crack, R. Hill 13 Musings on Theophilus, H. Eskildsen 14 Almost Full, R. Hill 16 Northern Moon, H. Eskildsen 17 Northwest Moon and Horrebow, H. Eskildsen 18 A Bit of Thebit, R. Hill 19 Euclides D in the Landscape of the Mare Cognitum (and Two Kipukas?), A. Anunziato 20 On the South Shore, R. Hill 22 Focus On: The Lunar 100, Features 11-20, J. Hubbell 23 Recent Topographic Studies 43 Lunar Geologic Change Detection Program T. Cook 120 Key to Images in this Issue 134 These are the modern Golden Days of lunar studies in a way, with so many new resources available to lu- nar observers. Recently, we have mentioned Robert Garfinkle’s opus Luna Cognita and the new lunar map by the USGS. This month brings us the updated, 7th edition of the Virtual Moon Atlas. These are all wonderful resources for your lunar studies. -

Glossary of Lunar Terminology

Glossary of Lunar Terminology albedo A measure of the reflectivity of the Moon's gabbro A coarse crystalline rock, often found in the visible surface. The Moon's albedo averages 0.07, which lunar highlands, containing plagioclase and pyroxene. means that its surface reflects, on average, 7% of the Anorthositic gabbros contain 65-78% calcium feldspar. light falling on it. gardening The process by which the Moon's surface is anorthosite A coarse-grained rock, largely composed of mixed with deeper layers, mainly as a result of meteor calcium feldspar, common on the Moon. itic bombardment. basalt A type of fine-grained volcanic rock containing ghost crater (ruined crater) The faint outline that remains the minerals pyroxene and plagioclase (calcium of a lunar crater that has been largely erased by some feldspar). Mare basalts are rich in iron and titanium, later action, usually lava flooding. while highland basalts are high in aluminum. glacis A gently sloping bank; an old term for the outer breccia A rock composed of a matrix oflarger, angular slope of a crater's walls. stony fragments and a finer, binding component. graben A sunken area between faults. caldera A type of volcanic crater formed primarily by a highlands The Moon's lighter-colored regions, which sinking of its floor rather than by the ejection of lava. are higher than their surroundings and thus not central peak A mountainous landform at or near the covered by dark lavas. Most highland features are the center of certain lunar craters, possibly formed by an rims or central peaks of impact sites. -

What's Hot on the Moon Tonight?: the Ultimate Guide to Lunar Observing

What’s Hot on the Moon Tonight: The Ultimate Guide to Lunar Observing Copyright © 2015 Andrew Planck All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any written, electronic, recording, or photocopying without written permission of the publisher or author. The exception would be in the case of brief quotations embodied in the critical articles or reviews and pages where permission is specifically granted by the publisher or author. Although every precaution has been taken to verify the accuracy of the information contained herein, the publisher and author assume no responsibility for any errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for damages that may result from the use of information contained within. Books may be purchased by contacting the publisher or author through the website below: AndrewPlanck.com Cover and Interior Design: Nick Zelinger (NZ Graphics) Publisher: MoonScape Publishing, LLC Editor: John Maling (Editing By John) Manuscript Consultant: Judith Briles (The Book Shepherd) ISBN: 978-0-9908769-0-8 Library of Congress Catalog Number: 2014918951 1) Science 2) Astronomy 3) Moon Dedicated to my wife, Susan and to my two daughters, Sarah and Stefanie Contents Foreword Acknowledgments How to Use this Guide Map of Major Seas Nightly Guide to Lunar Features DAYS 1 & 2 (T=79°-68° E) DAY 3 (T=59° E) Day 4 (T=45° E) Day 5 (T=24° E.) Day 6 (T=10° E) Day 7 (T=0°) Day 8 (T=12° W) Day 9 (T=21° W) Day 10 (T= 28° W) Day 11 (T=39° W) Day 12 (T=54° W) Day 13 (T=67° W) Day 14 (T=81° W) Day 15 and beyond Day 16 (T=72°) Day 17 (T=60°) FINAL THOUGHTS GLOSSARY Appendix A: Historical Notes Appendix B: Pronunciation Guide About the Author Foreword Andrew Planck first came to my attention when he submitted to Lunar Photo of the Day an image of the lunar crater Pitatus and a photo of a pie he had made. -

A Complete Bibliography of Publications in Isis, 1990–1999

A Complete Bibliography of Publications in Isis, 1990{1999 Nelson H. F. Beebe University of Utah Department of Mathematics, 110 LCB 155 S 1400 E RM 233 Salt Lake City, UT 84112-0090 USA Tel: +1 801 581 5254 FAX: +1 801 581 4148 E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] (Internet) WWW URL: http://www.math.utah.edu/~beebe/ 25 May 2018 Version 0.07 Title word cross-reference c [1275]. AΠOPHMA [2901]. BOTANIKON [2901]. ΠEPITΩNΠEΠONΘΩNTOΠΩN [1716]. ⊂ [431]. ⊃ [431]. -1708 [2436]. -4 [3189]. /Max [3367, 1215]. 0Die [1766]. 1 [1169, 2655, 2935, 566, 1131, 1939]. 1.7 [1001]. 1.7-7 [1001]. 10 [2649, 2983]. 100 [323]. 129 [1808]. 1333 [1938]. 1336 [2425]. 1345 [2250, 920]. 1400 [3429]. 1420 [2078]. 1450 [1797]. 1483 [348]. 150-Year [2452]. 1500 [29]. 1530 [30]. 1543 [441]. 1550 [2160, 3491, 1246]. 1570 [1998]. 1597 [3531]. 1600 [3326, 2734, 440, 151, 347]. 1610 [1724]. 1610/11 [1651]. 1620 [2652]. 1626 [2003]. 1632 [2000]. 1650 [1377]. 1653 [2901]. 1 2 1654 [2346]. 1657 [732]. 1659 [2816]. 1662 [357]. 1676 [1379, 452]. 1683 [1531]. 1685 [838]. 1687 [1976]. 1690 [2661]. 1696 [1531]. 1699 [835]. 1700 [34, 2491, 3315, 2975]. 1701 [2512]. 1715 [1820]. 1718 [2167]. 1727 [1193, 42]. 1730 [1733]. 1740 [2899]. 1742 [260]. 1750 [3140, 1479, 1560, 3142, 1286, 1566, 2746, 3141, 2351, 1385, 3404]. 1753 [456]. 1770 [460, 3152]. 1773 [3342]. 1777 [1483]. 1783 [2749]. 1785 [3057]. 1789 [461]. 1789/90 [461]. 1791 [3146]. 1792 [1734]. 1795 [2174, 165]. 1799 [561, 3442]. 17de [2814]. 1800 [2356, 326, 2412, 44, 923, 1928, 2902, 2101, 932, 245, 3590]. -

Science Concept 3: Key Planetary

Science Concept 6: The Moon is an Accessible Laboratory for Studying the Impact Process on Planetary Scales Science Concept 6: The Moon is an accessible laboratory for studying the impact process on planetary scales Science Goals: a. Characterize the existence and extent of melt sheet differentiation. b. Determine the structure of multi-ring impact basins. c. Quantify the effects of planetary characteristics (composition, density, impact velocities) on crater formation and morphology. d. Measure the extent of lateral and vertical mixing of local and ejecta material. INTRODUCTION Impact cratering is a fundamental geological process which is ubiquitous throughout the Solar System. Impacts have been linked with the formation of bodies (e.g. the Moon; Hartmann and Davis, 1975), terrestrial mass extinctions (e.g. the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary extinction; Alvarez et al., 1980), and even proposed as a transfer mechanism for life between planetary bodies (Chyba et al., 1994). However, the importance of impacts and impact cratering has only been realized within the last 50 or so years. Here we briefly introduce the topic of impact cratering. The main crater types and their features are outlined as well as their formation mechanisms. Scaling laws, which attempt to link impacts at a variety of scales, are also introduced. Finally, we note the lack of extraterrestrial crater samples and how Science Concept 6 addresses this. Crater Types There are three distinct crater types: simple craters, complex craters, and multi-ring basins (Fig. 6.1). The type of crater produced in an impact is dependent upon the size, density, and speed of the impactor, as well as the strength and gravitational field of the target. -

On the Diameter-Depth Relationship of Lunar Craters

Acta Universitatis Carolinae. Mathematica et Physica Jiří Bouška On the diameter-depth relationship of lunar craters Acta Universitatis Carolinae. Mathematica et Physica, Vol. 9 (1968), No. 2, 45--57 Persistent URL: http://dml.cz/dmlcz/142224 Terms of use: © Univerzita Karlova v Praze, 1968 Institute of Mathematics of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic provides access to digitized documents strictly for personal use. Each copy of any part of this document must contain these Terms of use. This paper has been digitized, optimized for electronic delivery and stamped with digital signature within the project DML-CZ: The Czech Digital Mathematics Library http://project.dml.cz 1968 ACTA UNIVERSITATIS CAROLINAE - MATHEMATICA ET PHYSICA No. 2, PAG. 45—57 PUBLICATION OF THE ASTRONOMICAL INSTITUTE OF THE CHARLES UNIVERSITY, No. 55 On the Diameter-Depth Relationship of Lunar Craters JlM BOUSKA Astronomical Institute, Faculty of Mathematics and Physics, Charles University, Prague (Received March 9, 1968) MacDonald's, Baldwin's, Markov's and present writer's results of the investigations of the diameter-depth relationship of lunar craters were analyzed. The relationship shows that all small craters are probably of impact origin. For many small lunar craters Ebert's rule is not valid. I. Introduction At the end of the last century Ebert (1890)* found that the ratios of the depths o of lunar craters to their diameters A decreased with increasing diameter. This relationship between diameter and depth of craters was later known as Ebert's rule. At Ebert's time only a few depths of lunar craters were known with sufficient accuracy. -

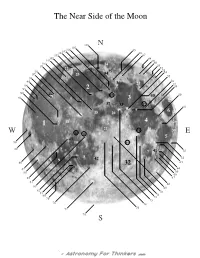

A Map of the Visible Side of the Moon

The Near Side of the Moon 108 N 107 106 105 45 104 46 103 47 102 48 101 49 100 24 50 99 51 52 22 53 98 33 35 54 97 34 23 55 96 95 56 36 25 57 94 58 93 2 92 44 15 40 59 91 3 27 37 17 38 60 39 6 19 20 26 28 1 18 4 29 21 11 30 W 12 E 14 5 43 90 10 16 89 7 41 61 8 62 9 42 88 32 63 87 64 86 31 65 66 85 67 84 68 83 69 82 81 70 80 71 79 72 73 78 74 77 75 76 S Maria (Seas) Craters 1 - Oceanus Procellarum (Ocean of Storms) 45 - Aristotles 77 - Tycho 2 - Mare Imbrium (Sea of Showers) 46 - Cassini 78 - Pitatus 3 - Mare Serenitatis (Sea of Serenity) 47 - Eudoxus 79 - Schickard 4 - Mare Tranquillitatis (Sea of Tranquility) 48 - Endymion 80 - Mercator 5 - Mare Fecunditatis (Sea of Fertility) 49 - Hercules 81 - Campanus 6 - Mare Crisium (Sea of Crises) 50 - Atlas 82 - Bulliadus 7 - Mare Nectaris (Sea of Nectar) 51 - Mercurius 83 - Fra Mauro 8 - Mare Nubium (Sea of Clouds) 52 - Posidonius 84 - Gassendi 9 - Mare Humorum (Sea of Moisture) 53 - Zeno 85 - Euclides 10 - Mare Cognitum (Known Sea) 54 - Menelaus 86 - Byrgius 18 - Mare Insularum (Sea of Islands) 55 - Le Monnier 87 - Billy 19 - Sinus Aestuum (Bay of Seething) 56 - Vitruvius 88 - Cruger 20 - Mare Vaporum (Sea of Vapors) 57 - Cleomedes 89 - Grimaldi 21 - Sinus Medii (Bay of the Center) 58 - Plinius 90 - Riccioli 22 - Sinus Roris (Bay of Dew) 59 - Magelhaens 91 - Galilaei 23 - Sinus Iridum (Bay of Rainbows) 60 - Taruntius 92 - Encke T 24 - Mare Frigoris (Sea of Cold) 61 - Langrenus 93 - Eddington 25 - Lacus Somniorum (Lake of Dreams) 62 - Gutenberg 94 - Seleucus 26 - Palus Somni (Marsh of Sleep)