The Origin and Evolution of Word Order

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete Bibliography (PDF)

COMPLETE BIBLIOGRAPHY OF THE PUBLICATIONS OF JOSEPH H. GREENBERG This bibliography follows the format of the bibliography published in On language (item 204, 723-37; with emendations) and the corrected supplemental bibliography in Language 78.560-64 (2002). The asterisked items have translations or reprints listed in the appendix to the bibliography. 1940 1. The decipherment of the Ben-Ali Diary, a preliminary statement. Journal of Negro History 25.372-75. 1941 *2. Some aspects of Negro-Mohammedan culture-contact among the Hausa. American Anthropologist 43.51-61. 3. Some problems in Hausa phonology. Language 17.316-23. 1946 *4. The influence of Islam on a Sudanese religion. New York: J.J. Augustin. Pp. ix, 73. 1947 5. Arabic loan-words in Hausa. Word 3.85-97. 6. Islam and clan organization among the Hausa. Southwestern Journal of Anthropology 3.193-211. *7. Swahili prosody. Journal of the American Oriental Society 67.24-30. 1948 8. The classification of African languages. American Anthropologist 50.24-30. *9. Linguistics and ethnology. Southwestern Journal of Anthropology 4.140-47. 10. The tonal system of Proto-Bantu. Word 4.196-208. 11. Review of H. Courlander & G. Herzog, The Cow-tail Switch and other West African tales. Journal of American Folklore 51.99-100. 1949 *12. Hausa verse prosody. Journal of the American Oriental Society 69.125-35. 13. The logical analysis of kinship. Philosophy of Science 16.58-64. *14. The Negro kingdoms of the Sudan. Transactions of the New York Academy of Sciences, Series II, 11.126-34. *15. Studies in African linguistic classification: I. -

An Amerind Etymological Dictionary

An Amerind Etymological Dictionary c 2007 by Merritt Ruhlen ! Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Greenberg, Joseph H. Ruhlen, Merritt An Amerind Etymological Dictionary Bibliography: p. Includes indexes. 1. Amerind Languages—Etymology—Classification. I. Title. P000.G0 2007 000!.012 00-00000 ISBN 0-0000-0000-0 (alk. paper) This book is dedicated to the Amerind people, the first Americans Preface The present volume is a revison, extension, and refinement of the ev- idence for the Amerind linguistic family that was initially offered in Greenberg (1987). This revision entails (1) the correction of a num- ber of forms, and the elimination of others, on the basis of criticism by specialists in various Amerind languages; (2) the consolidation of certain Amerind subgroup etymologies (given in Greenberg 1987) into Amerind etymologies; (3) the addition of many reconstructions from different levels of Amerind, based on a comprehensive database of all known reconstructions for Amerind subfamilies; and, finally, (4) the addition of a number of new Amerind etymologies presented here for the first time. I believe the present work represents an advance over the original, but it is at the same time simply one step forward on a project that will never be finished. M. R. September 2007 Contents Introduction 1 Dictionary 11 Maps 272 Classification of Amerind Languages 274 References 283 Semantic Index 296 Introduction This volume presents the lexical and grammatical evidence that defines the Amerind linguistic family. The evidence is presented in terms of 913 etymolo- gies, arranged alphabetically according to the English gloss. -

Joseph Harold Greenberg

JOSEPH HAROLD GREENBERG CORRECTED VERSION* Joseph H. Greenberg, one of the most original and influential linguists of the twentieth century, died at his home in Stanford, California, on May 7th, 2001, three weeks before his eighty-sixth birthday. Greenberg was a major pioneer in the development of linguistics as an empirical science. His work was always founded directly on quantitative data from a single language or from a wide range of languages. His chief legacy to contemporary linguistics is in the development of an approach to the study of language—typology and univerals—and to historical linguistics. Yet he also made major contributions to sociolinguistics, psycholinguistics, phonetics and phonology, morphology, and especially African language studies. Joe Greenberg was born on May 28th, 1915, in Brooklyn, New York, the second of two children. His father was a Polish Jew and his mother, a German Jew. His father’s family name was originally Zyto, but in one of those turn-of-the- century immigrant stories, he ended up taking the name of his landlord. Joe Greenberg’s early loves were music and languages. As a child he sat fascinated next to his mother while she played the piano, and asked her to teach him. She taught him musical notation and then found him a local teacher. Greenberg ended up studying with a Madame Vangerova, associated with the Curtis Institute of Music. Greenberg even gave a concert at Steinway Hall at the age of 14, and won a city-wide prize for best chamber music ensemble. But after finishing high school, Greenberg chose an academic career instead of a musical one, although he continued to play the piano every evening until near the end of his life. -

"Evolution of Human Languages": Current State of Affairs

«Evolution of Human Languages»: current state of affairs (03.2014) Contents: I. Currently active members of the project . 2 II. Linguistic experts associated with the project . 4 III. General description of EHL's goals and major lines of research . 6 IV. Up-to-date results / achievements of EHL research . 9 V. A concise list of actual problems and tasks for future resolution. 18 VI. EHL resources and links . 20 2 I. Currently active members of the project. Primary affiliation: Senior researcher, Center for Comparative Studies, Russian State University for the Humanities (Moscow). Web info: http://ivka.rsuh.ru/article.html?id=80197 George Publications: http://rggu.academia.edu/GeorgeStarostin Starostin Research interests: Methodology of historical linguistics; long- vs. short-range linguistic comparison; history and classification of African languages; history of the Chinese language; comparative and historical linguistics of various language families (Indo-European, Altaic, Yeniseian, Dravidian, etc.). Primary affiliation: Visiting researcher, Santa Fe Institute. Formerly, professor of linguistics at the University of Melbourne. Ilia Publications: http://orlabs.oclc.org/identities/lccn-n97-4759 Research interests: Genetic and areal language relationships in Southeast Asia; Peiros history and classification of Sino-Tibetan, Austronesian, Austroasiatic languages; macro- and micro-families of the Americas; methodology of historical linguistics. Primary affiliation: Senior researcher, Institute of Slavic Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences (Moscow / Novosibirsk). Web info / publications list (in Russian): Sergei http://www.inslav.ru/index.php?option- Nikolayev =com_content&view=article&id=358:2010-06-09-18-14-01 Research interests: Comparative Indo-European and Slavic studies; internal and external genetic relations of North Caucasian languages; internal and external genetic relations of North American languages (Na-Dene; Algic; Mosan). -

Survey of the World's Languages

Survey of the world’s languages The languages of the world can be divided into a number of families of related languages, possibly grouped into larger stocks, plus a residue of isolates, languages that appear not to be genetically related to any other known languages, languages that form one-member families on their own. The number of families, stocks, and isolates is hotly disputed. The disagreements centre around differences of opinion as to what constitutes a family or stock, as well as the acceptable criteria and methods for establishing them. Linguists are sometimes divided into lumpers and splitters according to whether they lump many languages together into large stocks, or divide them into numerous smaller family groups. Merritt Ruhlen is an extreme lumper: in his classification of the world’s languages (1991) he identifies just nineteen language families or stocks, and five isolates. More towards the splitting end is Ethnologue, the 18th edition of which identifies some 141 top-level genetic groupings. In addition, it distinguishes 1 constructed language, 88 creoles, 137 or 138 deaf sign languages (the figures differ in different places, and this category actually includes alternate sign languages — see also website for Chapter 12), 75 language isolates, 21 mixed languages, 13 pidgins, and 51 unclassified languages. Even so, in terms of what has actually been established by application of the comparative method, the Ethnologue system is wildly lumping! Some families, for instance Austronesian and Indo-European, are well established, and few serious doubts exist as to their genetic unity. Others are quite contentious. Both Ruhlen (1991) and Ethnologue identify an Australian family, although there is as yet no firm evidence that the languages of the continent are all genetically related. -

Corrections to and Clarifications of the Seri Data in Greenberg & Ruhlen's

Work Papers of the Summer Institute of Linguistics, University of North Dakota Session Volume 51 Article 2 2011 Corrections to and clarifications of the Seri data in Greenberg & Ruhlen's An Amerind Etymological Dictionary Stephen A. Marlett SIL-UND Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/sil-work-papers Part of the Linguistics Commons Recommended Citation Marlett, Stephen A. (2011) "Corrections to and clarifications of the Seri data in Greenberg & Ruhlen's An Amerind Etymological Dictionary," Work Papers of the Summer Institute of Linguistics, University of North Dakota Session: Vol. 51 , Article 2. DOI: 10.31356/silwp.vol51.02 Available at: https://commons.und.edu/sil-work-papers/vol51/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Work Papers of the Summer Institute of Linguistics, University of North Dakota Session by an authorized editor of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Corrections to and clarifications of the Seri data in Greenberg & Ruhlen’s An Amerind Etymological Dictionary Stephen A. Marlett Seri data have been included in comparative studies of Native American languages of North America, especially those that relate to the putative Hokan family and the putative Amerind family. Since the publication in recent years of much more analyzed Seri data, including those found in the 2005 dictionary, it is important to reassess the data that has been used in earlier comparative studies. This paper examines the data included in Greenberg & Ruhlen’s (2007) An Amerind Etymological Dictionary, corrects mistakes and clarifies the data generally.* The first comprehensive presentation of Greenberg’s view of Amerind (Greenberg 1987) appeared more than twenty years ago. -

Mother Tongue 24 Must Be Put Out, After All! the Key Findings Will Simply Be Numbered- No Special Order

MOTHER CONTENTS ASLIP Business plus Important Announcements TONGUE 4 Obituaries: John Swing Rittershofer (1941-1994) 6 Reviews of Cavalli-Sforza et al's History and Geography of Human Genes. Reviewed by: Rebecca L. Cann, Frank B. Livingstone, and NEWSLETIER OF Hal Fleming THE ASSOCIATION 30 The "Sogenannten" Ethiopian Pygmoids: Hal Fleming FOR THE STUDY OF 34 Long-Range Linguistic Relations: Cultural Transmission or Consan lANGUAGE IN guinity?: Igor M Diakonoff 41 Statistics and Historical Linguistics: Some Comments PREHISTORY Sheila Embleton 46 A Few Remarks on Embleton's Comments: Hal Fleming 50 On the Nature of the Algonquian Evidence for Global Etymologies Marc Picard 55 Greenberg Comments on Campbell and Fleming Joseph H. Greenberg 56 A Few Delayed Final Remarks on Campbell's African Section Hal Fleming 57 Some Questions and Theses for the American Indian Language Classification Debate (ad Campbell, 1994): John D. Bengtson 60 A Note on Amerind Pronouns: Merritt Ruhlen 62 Regarding Native American Pronouns: Ives Goddard 65 Two Aspects of Massive Comparisons: Hal Fleming 69 Proto-Amerind *qets' 'left (hand)': Merritt Ruhlen 71 Arapaho, Blackfoot, and Basque: A "Snow" Job: Marc Picard 73 World Archaeological Congress 3. Summary by: Roger Blench 76 Comment on Roger Blench's Report on World Archaeological Congress: Hal Fleming 77 Announcement: Seventh Annual UCLA Indo-European Conference 78 Announcement: 11th Annual Meeting of the Language Origins Society 79 Quick Notes 86 A Valediction of Sorts: Age Groups, Jingoists, and Stuff Hal Fleming Issue 24, March 1995 MOTHER TONGUE Issue 24, March 1995 OFFICERS OF ASLIP (Address appropriate correspondence to each.) President: Harold C. -

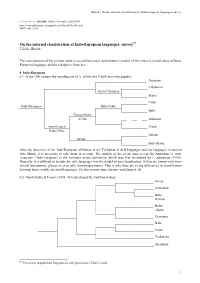

Blažek : on the Internal Classification of Indo-European Languages: Survey

Blažek : On the internal classification of Indo-European languages: survey Linguistica ONLINE. Added: November 22nd 2005. http://www.phil.muni.cz/linguistica/art/blazek/bla-003.pdf ISSN 1801-5336 On the internal classification of Indo-European languages: survey[*] Václav Blažek The main purpose of the present study is to confront most representative models of the internal classification of Indo- European languages and their daughter branches. 0. Indo-European 0.1. In the 19th century the tree-diagram of A. Schleicher (1860) was very popular: Germanic Lithuanian Slavo-Lithuaian Slavic Celtic Indo-European Italo-Celtic Italic Graeco-Italo- -Celtic Albanian Aryo-Graeco- Greek Italo-Celtic Iranian Aryan Indo-Aryan After the discovery of the Indo-European affiliation of the Tocharian A & B languages and the languages of ancient Asia Minor, it is necessary to take them in account. The models of the recent time accept the Anatolian vs. non- Anatolian (‘Indo-European’ in the narrower sense) dichotomy, which was first formulated by E. Sturtevant (1942). Naturally, it is difficult to include the relic languages into the model of any classification, if they are known only from several inscriptions, glosses or even only from proper names. That is why there are so big differences in classification between these scantily recorded languages. For this reason some scholars omit them at all. 0.2. Gamkrelidze & Ivanov (1984, 415) developed the traditional ideas: Greek Armenian Indo- Iranian Balto- -Slavic Germanic Italic Celtic Tocharian Anatolian [*] Previously unpublished. Reproduced with permission. [Editor’s note] 1 Blažek : On the internal classification of Indo-European languages: survey 0.3. -

Proto-Amerind Numerals

Anthropol. Sci. 103(3), 209-225, 1995 Proto-Amerind Numerals MERRITT RUHLEN 4335 Cesano Court, Palo Alto, CA 94306, U.S.A. Received December 5, 1995 •ôGH•ô Abstract•ôGS•ô The Amerind language family includes all the aboriginal languages of North and South America, except for those belonging to the Eskimo-Aleut and Na- Dene families. Comparative linguistic evidence from extant (or attested) Amerind languages indicates that Proto-Amerind-the language from which all Amerind languages derive-used a system of counting in which an obligatory numeral prefix, •ôUH•ô*•ôUS•ô•ôNH•ône•ôNS•ô-,preceded the numeral root. The first three numerals in Proto-Amerind seem to have been •ôUH•ô*•ôUS•ô•ôNH•ône•ôNS•ô-•ôNH•ôk'•ôUH•ôw•ôUS•ôe•ôNS•ô`1,' •ôUH•ô*•ôUS•ô•ôNH•ône-pale•ôNS•ô`2,' and •ôUH•ô*•ôUS•ô•ôNH•ône-q•ôUH•ôw•ôUS•ôalas•ôNS•ô `3.' A fourth numeral, Proto-Amerind •ôUH•ô*•ôUS•ô•ôNH•ôta-pale•ôNS•ô`4,' combined a reflexive prefix with the Proto- Amerind root for `2' in order to express the number `4.' •ôGH•ô Key Words•ôNS•ô: anthropological linguistics, Amerind languages, numerals INTRODUCTION The Amerind language family, as defined by Joseph Greenberg (1987), includes all the indigenous languages of the Americas, with the exception of those belonging to the Eskimo-Aleut and Na-Dene families1. The Eskimo-Aleut family consists of what are essentially two languages, spread across the northern periphery of North America from Alaska to Greenland. The Na-Dene family consists of four branches, three of which-Haida, Tlingit, and Eyak-are single languages. -

Proto Indo-European (PIE)

LING 322 MIDDLE ENGLSH: LANGUAGE AND CHANGE The road to PROTO INDO EUROPEAN (PIE) The origin of language Problematic Recent work in comparative linguistics suggests that all, or almost all, attested human languages may derive from a single earlier language. Hypotheses of origin Continuity theory: Complexity of language indicates gradual evolution from pre- linguistic systems among early primates Discontinuity theory: Human language is unique and cannot be compared to any non-human system, so language must have appeared fairly suddenly in human evolution Monogenesis: a single proto-language between 200,000 and 50,000 years ago Polygenesis: languages evolved in several lineages independent of one another Complicating factors in the search for origins Time languages develop and change in a variety of ways Diverge Diachronic change Converge Two or more unrelated languages in contact acquire and display similar linguistic features not inherited from their respective proto- languages Replacement Speakers gradually shift to a completely different language Complete loss A crucial part of the language jigsaw is lost : Hittite The First Language Genetic and archaeological evidence suggests that Homo Sapiens originated in and spread from East Africa, so maybe an ancestor of the Khoisan languages, spoken around 50,000 years ago Evidence? The nature of reconstructed proto-languages suggests older languages made more phonological and morphological distinctions than their descendants. Evidence cited includes Khoisan languages have ‘click’ sounds, no -

When Ruhlen's `Mother Tongue' Theory Meets the Null Hypothesis

When Ruhlen's ‘mother tongue’ theory meets the null hypothesis Louis-Jean Boë†, Pierre Bessière‡ and Nathalie Vallée† † ICP Université Stendhal, INPG, CNRS, Grenoble, France ‡ GRAVIR, CNRS, Grenoble France E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT project to try to understand why some interdisciplinary fields, such as linguistics, are attracted by theories that are The demonstration of a relationship between languages ill founded. We intend to investigate why there is can depend on finding words of similar phonological continued propagation of such theories while the proof of shape and roughly equivalent meaning. But it must be their validity has not been established or even that they shown that the similarities observed could not have arisen have been falsified. Our project is called Representation by chance. That is to say, the null hypothesis can be and diffusion of scientific ideas in speech and language rejected. We demonstrate, by a simple application of sciences [17-18]. probability theory, that the world roots proposed for a For centuries, theories addressing the origin of man and Proto-Sapiens language by Merritt Ruhlen in The origin of the origin of languages have been closely linked. In the Languages are the result of random chance. The null XVIIth century the old interest in the origin of language hypothesis can not be rejected. The author used too few and the identity of mankind was rekindled and became a roots, too many equivalent meanings, too many languages dominant subject of discussion, but in the orthodox view, per family, and too many phonological equivalences for a the Bible was still the main source of information about too small number of different phonological shapes. -

Origin and Development of Language in South Asia: Phylogeny Versus Epigenetics?

Origin and Development of Language in South Asia: Phylogeny Versus Epigenetics? The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Witzel, Michael E. J. Origin and development of language in South Asia: Phylogeny versus epigenetics? Paper presented at Darwin and Evolution, mid-year meeting of the Indian Academy of Sciences, Hyderabad, India, July 3, 2009. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:8554510 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA 2 Origin and development of language in South Asia: Phylogeny versus epigenetics? MICHEL WITZEL Department of Sanskrit and Indian Studies, Harvard University, 1 Bow Street, Cambridge MA 02138, USA Email: [email protected] SUMMARY his presentation begins with a brief overview of opinions on Tthe origin of human language and the controversial question of Neanderthal speech. Moving from the language of the ‘African Eve’ to the specific ones of the subcontinent, a brief overview is given of the prehistoric and current South Asian language families as well as their development over the past c. 5000 years. The equivalents of phylogeny and epigenetics in linguistics are then dealt with, that is, the successful Darwinian-style phylogenetic reconstruction of language families (as ‘trees’), which is interfered with by the separate wave-like spread of certain features across linguistic boundaries, even across language families.