Tony Latone: the Hero of Pottsville

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Statistical Leaders of the ‘20S

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 14, No. 2 (1992) Statistical Leaders of the ‘20s By Bob GIll Probably the most ambitious undertaking in football research was David Neft’s effort to re-create statistics from contemporary newspaper accounts for 1920-31, the years before the NFL started to keep its own records. Though in a sense the attempt had to fail, since complete and official stats are impossible, the results of his tireless work provide the best picture yet of the NFL’s formative years. Since the stats Neft obtained are far from complete, except for scoring records, he refrained from printing yearly leaders for 1920-31. But it seems a shame not to have such a list, incomplete though it may be. Of course, it’s tough to pinpoint a single leader each year; so what follows is my tabulation of the top five, or thereabouts, in passing, rushing and receiving for each season, based on the best information available – the stats printed in Pro Football: The Early Years and Neft’s new hardback edition, The Football Encyclopedia. These stats can be misleading, because one man’s yardage total will be based on, say, five complete games and four incomplete, while another’s might cover just 10 incomplete games (i.e., games for which no play-by-play accounts were found). And then some teams, like Rock Island, Green Bay, Pottsville and Staten Island, often have complete stats, based on play-by-plays for every game of a season. I’ll try to mention variations like that in discussing each year’s leaders – for one thing, “complete” totals will be printed in boldface. -

2020 MLB Ump Media Guide

the 2020 Umpire media gUide Major League Baseball and its 30 Clubs remember longtime umpires Chuck Meriwether (left) and Eric Cooper (right), who both passed away last October. During his 23-year career, Meriwether umpired over 2,500 regular season games in addition to 49 Postseason games, including eight World Series contests, and two All-Star Games. Cooper worked over 2,800 regular season games during his 24-year career and was on the feld for 70 Postseason games, including seven Fall Classic games, and one Midsummer Classic. The 2020 Major League Baseball Umpire Guide was published by the MLB Communications Department. EditEd by: Michael Teevan and Donald Muller, MLB Communications. Editorial assistance provided by: Paul Koehler. Special thanks to the MLB Umpiring Department; the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum; and the late David Vincent of Retrosheet.org. Photo Credits: Getty Images Sport, MLB Photos via Getty Images Sport, and the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Copyright © 2020, the offiCe of the Commissioner of BaseBall 1 taBle of Contents MLB Executive Biographies ...................................................................................................... 3 Pronunciation Guide for Major League Umpires .................................................................. 8 MLB Umpire Observers ..........................................................................................................12 Umps Care Charities .................................................................................................................14 -

23 Guys with Hobbies

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 9, No. 7 (1987) 23 GUYS WITH HOBBIES By L. Robert Davids The decision by Bo Jackson, who played hit-or-miss baseball for the Kansas City Royals this summer, to play with the Los Angeles Raiders this fall, has been greeted with some skepticism. Well, it has been many years since an athlete has attempted this dual role in the same year. The last time was in 1954 when Vic Janowicz, the only other Heisman Trophy winner to play major league baseball, was a substitute third baseman for the Pittsburgh Pirates. He batted only .151 in 41 games. He performed better as a halfback for the Washington Redskins, but certainly did not star that year. Of the approximately 60 athletes who played both major league baseball and football since 1920, a surprising 23 did it in the same year. Almost all of these multiple efforts were made in the early decades when the baseball and football seasons did not overlap as much as they do now. Also, several of the players made only token appearances in one of the sports, usually baseball. Tom Whelan and Red Smith played in only one game each, Jahn Scalzi in two, and John Mohardt in five. However, the latter had only one official at bat and collected a hit for a "lifetime" 1000 average! Only one or two players performed reasonably well in both sports the same year. In 1926, Garland "Gob" Buckeye, the 260-pound southpaw hurler for the Cleveland Indians, had a fine 3.10 ERA in 166 innings in that heavy-hitting season. -

Rademacher Dream Ended, Hr Vjwhwl

CLASSIFIED ADS, Pages C-6-14 C IMMHMMHHH W)t fining sHaf SPORTS WASHINGTON, D. C., FRIDAY, AUGUST 23, 1957 kk . Y^k Rademacher Dream Ended, Hr VjwHwl , . ¦ ¦ |f But He Gave It a Good Try , */ Patterson Wins by KO in 6 - LoughranSays • / . a- '•* %>¦ ' Injury ' •%* ,%¦ :&# :? .. V\fefit#%. ;; *• Musial'* ; .: *., : *£>• ':-:->\ :, ', ¦ k- ..::s. .. -.<• tl> Sg| **&(<.¦¦¦¦• ¦m& ?:sWW*fc WMW•-•••- W'?r***Y:J;'*•':. :*.V« t:s' : . :t: ', • >,- . *.£;* ' ?• . •;'-^ Being r ’v. x ; c.s-\ .*¦ Loser Should After Down Himself SEATTLE, Aug. 23 TP).—Floyd Patterson, the cool de- IgF Cripples Cards Up Ring stroyer who holds the world heavyweight championship, cut Give down powerful Pete Rademacher last night and ended A — SEATTLE, Aug. 23 (A*). the big ex-football player’s dream of stepping from the SB • Bp SsE . K» Referee Loughran, Tommy one amateur peak to the pinnacle of the pros. For 10 Days of the great light-heavyweight away pounds—the champion weighed champions of yesteryear, today Giving 15 187 to By the Associated Press advised Pete Rademacher to Rademacher’s 202 Floyd " The pennant hopes of the quit the ring. decked the courageous chal- . and hurt, and the few blows he St. Louis Cardinals were hand- At the same time he said lenger seven times at Sick’s ] landed in the sixth lacked sting. ed a devastating blow today Floyd Patterson could become Stadium before Pete took the ; He clinched and, as Loughran when Stan Musial learned that as great a heavyweight cham- full count at 2:57 of the sixth i moved in to separate them Pat- he will be out of action for 10 pion as Jack Dempsey. -

Glenn Killinger, Service Football, and the Birth

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School School of Humanities WAR SEASONS: GLENN KILLINGER, SERVICE FOOTBALL, AND THE BIRTH OF THE AMERICAN HERO IN POSTWAR AMERICAN CULTURE A Dissertation in American Studies by Todd M. Mealy © 2018 Todd M. Mealy Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2018 ii This dissertation of Todd M. Mealy was reviewed and approved by the following: Charles P. Kupfer Associate Professor of American Studies Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee Simon Bronner Distinguished Professor Emeritus of American Studies and Folklore Raffy Luquis Associate Professor of Health Education, Behavioral Science and Educaiton Program Peter Kareithi Special Member, Associate Professor of Communications, The Pennsylvania State University John Haddad Professor of American Studies and Chair, American Studies Program *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines Glenn Killinger’s career as a three-sport star at Penn State. The thrills and fascinations of his athletic exploits were chronicled by the mass media beginning in 1917 through the 1920s in a way that addressed the central themes of the mythic Great American Novel. Killinger’s personal and public life matched the cultural medley that defined the nation in the first quarter of the twentieth-century. His life plays outs as if it were a Horatio Alger novel, as the anxieties over turn-of-the- century immigration and urbanization, the uncertainty of commercializing formerly amateur sports, social unrest that challenged the status quo, and the resiliency of the individual confronting challenges of World War I, sport, and social alienation. -

Lafayette Football 1913-1925 1913 (4-5-1) 1919 (6-2) 11/15 Alfred

tHe tRaDItIon 2011 lafayette football 99 tRaDItIon of excellence mIlestone football WIns lafayette Ranks 36tH In Since fielding its first college football team in the fall of 1882, all-tIme WIns Lafayette has had a proud, colorful gridiron tradition on the way to Lafayette College fielded its first football team in 1882 and won a total of 633 victories. Football followers on College Hill have been its first game in the fourth contest of the following season, beating able to lay claim to two outright national championships and a share Rutgers, 25-0. Since that win, the Leopards have joined the elite of still another. In 1896, Lafayette and Princeton both claimed a piece group of institutions with 600 or more football victories. Lafayette of the national championship following a scoreless tie. The Leopards played its 1,000th football game on Sept. 16, 1989, and was the first finished the season 11-0-1 while the Tigers were 10-0-1. Undefeated founding Patriot League school to eclipse the 500-victory plateau. 9-0 records in 1921 and 1926 gave Lafayette followers reason to believe they were number one in the country both seasons. Rank School NCAA Division # of Wins 1. Michigan FBS 884 Victory # Year Opponent (Score) 2. Yale FCS 864 1 1883 Rutgers (25-0) 3. Texas FBS 850 58 1896 Princeton (0-0) 4. Notre Dame FBS 844 (tied for national championship) 5. Nebraska FBS 837 100 1900 Dickinson (10-6) 6. Ohio State FBS 830 7. Alabama FBS 823 200 1915 Pennsylvania (17-0) 8. Penn State FBS 818 231 1921 Lehigh (28-6) 9. -

SPORTS Tigers May Give Cramer for Weatherly by LEO MACDONELL V THEY FLY for BASKETS at OSHKOSH Deal with Tribe Wisterias Tale Steals If

PAGE 30 D K THOI T KVEN IN <1 TIM K S O'HDSK CHKKKY 8800) Thursday, 3, 1942 SPORTS Tigers May Give Cramer for Weatherly By LEO MACDONELL v THEY FLY FOR BASKETS AT OSHKOSH Deal With Tribe Wisterias Tale Steals If. E*rr &r' rr Svc'esoiue ot H, A er Has Writers, Show at U. M. ‘lhisl* Be RecruTra 4 Dv.*'es at Qrea* Le*es .es’s : -i "he Aisles Listed in Rumors By 808 MURTHY Michigan's 1942 football team now why he »howMl roe thoa* , TRIED TO SELL PLAYER WHO'S IN ARM\ ¦T ¦ ¦ picture*. I’m glad he did.” today wears its gi*ld M’ rings on The big fellow talked with such Meet precious At Dull the outside and a lot of you CHICAGO. iVc. .3 Lt. Gordon 'Mickey) Cochrane, ft sincerity that could hav# memories on the insidp. heard a pin drop in the big ball- front Gtent Irak's now that his visitor at bafteha!! headquartc*¦* By room that was parked to capacity, LEO MACDONELL The annual Michigan Rust wa* * • t ver. expecti t he wig ed to ruitir . • Wiatert told how ¦ r¦ CHICAGO. Dec. 3—With the held last night at Hotel Stailcr one night rode him all around Ann Grev Lakes eleven and before that Hr acted as a scout for the dreariest meetings in major league and. as always, the outgoing Arbor. That was at the end of hit he was of ourr-e. manager of the stations championship base- history fast earning lo an inglori- ball ‘earn. -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig -

PDF of Apr 15 Results

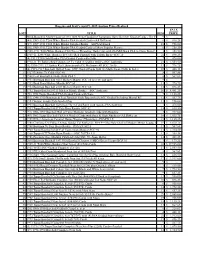

Huggins and Scott's April 9, 2015 Auction Prices Realized SALE LOT# TITLE BIDS PRICE 1 Mind-Boggling Mother Lode of (16) 1888 N162 Goodwin Champions Harry Beecher Graded Cards - The First Football9 $ Card - in History! [reserve not met] 2 (45) 1909-1911 T206 White Border PSA Graded Cards—All Different 6 $ 896.25 3 (17) 1909-1911 T206 White Border Tougher Backs—All PSA Graded 16 $ 956.00 4 (10) 1909-1911 T206 White Border PSA Graded Cards of More Popular Players 6 $ 358.50 5 1909-1911 T206 White Borders Hal Chase (Throwing, Dark Cap) with Old Mill Back PSA 6--None Better! 3 $ 358.50 6 1909-11 T206 White Borders Ty Cobb (Red Portrait) with Tolstoi Back--SGC 10 21 $ 896.25 7 (4) 1911 T205 Gold Border PSA Graded Cards with Cobb 7 $ 478.00 8 1910-11 T3 Turkey Red Cabinets #9 Ty Cobb (Checklist Offer)--SGC Authentic 21 $ 1,553.50 9 (4) 1910-1911 T3 Turkey Red Cabinets with #26 McGraw--All SGC 20-30 11 $ 776.75 10 (4) 1919-1927 Baseball Hall of Fame SGC Graded Cards with (2) Mathewson, Cobb & Sisler 10 $ 448.13 11 1927 Exhibits Ty Cobb SGC 40 8 $ 507.88 12 1948 Leaf Baseball #3 Babe Ruth PSA 2 8 $ 567.63 13 1951 Bowman Baseball #253 Mickey Mantle SGC 10 [reserve not met] 9 $ - 14 1952 Berk Ross Mickey Mantle SGC 60 11 $ 776.75 15 1952 Bowman Baseball #101 Mickey Mantle SGC 60 12 $ 896.25 16 1952 Topps Baseball #311 Mickey Mantle Rookie—SGC Authentic 10 $ 4,481.25 17 (76) 1952 Topps Baseball PSA Graded Cards with Stars 7 $ 1,135.25 18 (95) 1948-1950 Bowman & Leaf Baseball Grab Bag with (8) SGC Graded Including Musial RC 12 $ 537.75 19 1954 Wilson Franks PSA-Graded Pair 11 $ 956.00 20 1955 Bowman Baseball Salesman Three-Card Panel with Aaron--PSA Authentic 7 $ 478.00 21 1963 Topps Baseball #537 Pete Rose Rookie SGC 82 15 $ 836.50 22 (23) 1906-1999 Baseball Hall of Fame Manager Graded Cards with Huggins 3 $ 717.00 23 (49) 1962 Topps Baseball PSA 6-8 Graded Cards with Stars & High Numbers--All Different 16 $ 1,015.75 24 1909 E90-1 American Caramel Honus Wagner (Throwing) - PSA FR 1.5 21 $ 1,135.25 25 1980 Charlotte O’s Police Orange Border Cal Ripken Jr. -

History: Head Coaches

WE ARE SPARTANS MICHIGAN STATE FOOTBALL HISTORY: HEAD COACHES COACH (ALMA MATER) PERIOD YEARS G W-L-T PCT. No established coach 1896 (1) 4 1-2-1 .375 Henry Keep 1897-98 (2) 14 8-5-1 .609 Charles O. Bemies (West Theo. Sem.) 1899-1900 (2) 11 3-7-1 .318 George E. Denman (West Theo. Sem.) 1901-02 (2) 17 7-9-1 .441 Chester L. Brewer (Wisconsin) 1903-10 (8) 70 54-10-6 .814 John F. Macklin (Pennsylvania) 1911-15 (5) 34 29-5 .853 Frank Sommers (Pennsylvania) 1916 (1) 7 4-2-1 .642 Chester L. Brewer (Wisconsin) 1917 (1) 9 0-9 .000 George E. Gauthier (Michigan State) 1918 (1) 7 4-3 .571 Chester L. Brewer (Wisconsin) 1919 (1) 9 4-4-1 .500 George “Potsy” Clark (Illinois) 1920 (1) 10 4-6 .400 Albert M. Barron (Penn State) 1921-22 (2) 18 6-10-2 .389 Ralph H. Young (Chicago-W&J) 1923-27 (5) 41 18-22-1 .451 Harry G. Kipke (Michigan 1925) 1928 (1) 8 3-4-1 .437 James H. Crowley (Notre Dame 1925) 1929-32 (4) 33 22-8-3 .712 Charles W. Bachman (Notre Dame 1917) 1933-46 (13) 114 70-34-10 .658 Clarence “Biggie” Munn (Minnesota 1932) 1947-53 (7) 65 54-9-2 .857 Hugh Duffy Daugherty (Syracuse 1940) 1954-72 (19) 183 109-69-5 .609 Dennis E. Stolz (Alma 1955) 1973-75 (3) 33 19-13-1 .591 Darryl D. Rogers (Fresno State 1957) 1976-79 (4) 44 24-18-2 .568 Frank “Muddy” Waters (Michigan State 1950) 1980-82 (3) 33 10-23 .303 George J. -

NPRC) VIP List, 2009

Description of document: National Archives National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) VIP list, 2009 Requested date: December 2007 Released date: March 2008 Posted date: 04-January-2010 Source of document: National Personnel Records Center Military Personnel Records 9700 Page Avenue St. Louis, MO 63132-5100 Note: NPRC staff has compiled a list of prominent persons whose military records files they hold. They call this their VIP Listing. You can ask for a copy of any of these files simply by submitting a Freedom of Information Act request to the address above. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. -

Ttfrnniminim Continued from Page 41

ttfrnniMiniM continued from page 41 No doubt. But the nation's sports fans never accepted them as middle-aged or elderly men. To the fans, the Horsemen remained the speedsters who went un beaten their senior (1924) season and lost only two games, both to Nebraska, in three years. It was an era when people thirsted 1 -ill; for sports heroes. Ruth ... Dempsey ... I f Tilden ... and then stars to represent college football and its No. 1 coach, Rockne. Certainly, there were bigger back- fields and probably better. But, as Rockne explained years later in a letter to New York columnist Joe Williams, the Horsemen remained something special. "Somehow," Rock wrote, "they seemed to go to town whenever the oc casion demanded. I've never seen a team with more poise, emotionally or physically. In their senior year, they had Ten years later, the Horsemen gathered for a class reunion: (L-R) Jim Crowley, Elmer every game won before they played it. I Layden, Don Miller, and Harry Stuhldreher. can still hear Stuhldreher saying at the start of a game, 'Come on! Let's get sons in catching passes. His 60 points Rock switched Layden to fullback, unit some points quick before these guys made him 1923 scoring co-leader. He ing the Horsemen as a unit late in the wake up and get the idea they can beat was Irish rushing leader with 698 and '22 season. "Layden's terrific speed," Rockne us'." 763 yards in '23 and '24. This was quite a change from Rock's Judge MUler, the only Horseman who said, "made him one of the most un first impression of the Horsemen.