Free-Trade Ferries: a Case for Competition Alexander Philipatos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manly Ferry Timetable

F1 Manly How to use this timetable Fares This timetable provides a snap shot of service information in 24-hour time (e.g. 5am = 05:00, 5pm = 17:00). To travel on public transport in Sydney and surrounding regions, an Opal card is the cheapest and easiest ticket Information contained in this timetable is subject to change without notice. Please note that timetables do not option. include minor stops, additional trips for special events, short term changes, holiday timetable changes, real-time An Opal card is a smartcard you keep and reuse. You put credit onto the card then tap on and tap off to pay information or any disruption alerts. your fares throughout Sydney, the Blue Mountains, Central Coast, Southern Highlands, Hunter and the South For the most up-to-date times, use the Trip Planner or Departures on transportnsw.info Coast. Real-time planning Fares are based on: the type of Opal card you use You can plan your trip with real-time information using the Trip Planner or Departures on transportnsw.info or by downloading travel apps on your smartphone or tablet. the distance you travel from tap on to tap off The Trip Planner, Departures and travel apps offer various features: the mode of transport you choose favourite your regular trips any Opal benefits such as discounts and capped fares that apply see where your service is on the route Find out more about Opal fares and benefits at transportnsw.info/opal get estimated pick up and arrival times You can use a contactless-enabled Mastercard® card or mobile device to pay your fare on F1 Manly Ferries. -

Anacortes Museum Research Files

Last Revision: 10/02/2019 1 Anacortes Museum Research Files Key to Research Categories Category . Codes* Agriculture Ag Animals (See Fn Fauna) Arts, Crafts, Music (Monuments, Murals, Paintings, ACM Needlework, etc.) Artifacts/Archeology (Historic Things) Ar Boats (See Transportation - Boats TB) Boat Building (See Business/Industry-Boat Building BIB) Buildings: Historic (Businesses, Institutions, Properties, etc.) BH Buildings: Historic Homes BHH Buildings: Post 1950 (Recommend adding to BHH) BPH Buildings: 1950-Present BP Buildings: Structures (Bridges, Highways, etc.) BS Buildings, Structures: Skagit Valley BSV Businesses Industry (Fidalgo and Guemes Island Area) Anacortes area, general BI Boat building/repair BIB Canneries/codfish curing, seafood processors BIC Fishing industry, fishing BIF Logging industry BIL Mills BIM Businesses Industry (Skagit Valley) BIS Calendars Cl Census/Population/Demographics Cn Communication Cm Documents (Records, notes, files, forms, papers, lists) Dc Education Ed Engines En Entertainment (See: Ev Events, SR Sports, Recreation) Environment Env Events Ev Exhibits (Events, Displays: Anacortes Museum) Ex Fauna Fn Amphibians FnA Birds FnB Crustaceans FnC Echinoderms FnE Fish (Scaled) FnF Insects, Arachnids, Worms FnI Mammals FnM Mollusks FnMlk Various FnV Flora Fl INTERIM VERSION - PENDING COMPLETION OF PN, PS, AND PFG SUBJECT FILE REVIEW Last Revision: 10/02/2019 2 Category . Codes* Genealogy Gn Geology/Paleontology Glg Government/Public services Gv Health Hl Home Making Hm Legal (Decisions/Laws/Lawsuits) Lgl -

Parry Report (Ministerial Inquiry Into Sustainable Transport

Ministerial inquiry into sustainable transport in New South Wales Options for the future INTERIM REPORT August 2003 iii Contents Overview ix Summary of reform options xvii 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Terms of reference for this inquiry 1 1.2 Report structure 2 2 Overview of public transport in New South Wales 4 2.1 Transport in the Greater Sydney Area 5 2.2 Transport in rural and regional New South Wales 7 2.3 The Commonwealth Government and public transport in New South Wales 8 2.4 Rail services in New South Wales 10 2.5 Public bus and ferry services 13 2.6 Private bus services 16 2.7 Other services 18 3 Challenges in delivering better services in the Greater Sydney Area 19 3.1 Challenges to improving services in rail 19 3.2 The need for bus reform 30 3.3 Achieving efficiencies in ferry services 32 3.4 The potential for expansion of light rail 33 4 Revenue needs for the government-operated public transport network 35 4.1 Revenue needs for metropolitan rail 38 4.2 Revenue needs for STA buses 48 4.3 Revenue needs for Sydney Ferries 53 4.4 Revenue needs for CountryLink 56 5 Funding options 58 MINISTERIAL INQUIRY INTO SUSTAINABLE TRA NSPORT IN NEW SOUTH WALES iv CONTENTS 5.1 Principal funding sources 59 5.2 Criteria for assessing funding options 60 5.3 User-pays funding options 61 5.4 Beneficiary-pay funding sources 62 5.5 Private funding options 69 5.6 Public investment options 76 5.7 Summary of funding options 80 5.8 Observations 81 6 Fair fares: equity and efficiency 83 6.1 Requirements for public transport fare structures 84 6.2 Existing ticketing -

27Th October 2012

Baragoola Week Ending 27th October 2012 In attendance this week (members): Ernie, Peter C, Peter H, Peter M, Geoff E, Nick, Lance, Glen and Ross Visitors: nil Upcoming events Baragoola Preservation Association Member Christmas Party (details soon) Historic Manly ferry events this week 2nd November 1878 – Fairlight arrives Sydney 29th October 1905 – Binngarra runs first revenue service to Manly 1st November 1905 – Binngarra’s first accident – collision with Circular Quay retaining wall Fundraising Information We need to raise an additional $24,540 in the next couple of months and all donations are very welcome. Donations $2 and above are tax deductible so please consider making a donation to help save this very last original Manly ferry for generations to come. Committee News Nothing from the committee this week! Finances Our bank balance increased by $290 this week From the editor Our new postal address: PO Box 374 Crows Nest, NSW, 1585 Please ensure you address any correspondence to this address in future. Over the coming weeks and months we will be increasing our fundraising activities and looking at ways to vastly ramp up our ability to earn money. The restoration of Baragoola needs a large sum of money – we are totally funded by donations and will be seeking ways to interest large commercial donors and sponsors – for this we need the help of all association members and are looking to the broader membership to assist. The small amounts we gain through private donations and sale of items is enough for the day to day running of the association, but we need some serious money if we are to achieve our goal of getting Baragoola slipped and the hull repaired (or areas replaced as needed) if we are to keep this important heritage item going as a viable entity for many years to come. -

From Scots to Australians

FROM SCOTS TO AUSTRALIANS THE CARMENT AND INGLIS FAMILIES 1672-1976 David Carment Published by David Carment First published 2013 by David Carment, 11 Fairfax Road, Mosman N.S.W. 2088, Australia, [email protected] Copyright for text: David Carment Unless otherwise indicated, all images reproduced in this book belong to members of the Carment, George, Inglis, McAlpine, Sulman and Wood families. ISBN: 978-0-646-59524-5 3 CONTENTS PREFACE 6 PART A THE CARMENT FAMILY 1. Carment Beginnings 12 2. David Carment and Margaret Stormonth 20 3. James Carment and Elizabeth Charlotte Maxwell 43 4. David Carment and Elizabeth Shallard 59 5. David Shallard Carment and Ida Marion Arbuckle Mackie 80 PART B THE INGLIS FAMILY 6. William Inglis and Mary Ann Ferguson 111 7. Violet Louise Inglis 151 CONCLUSION Scottish-Australian Lives 180 INDEX 184 4 5 PREFACE The eminent Australian historian Graeme Davison observes that in ‘family history, even more than other forms of history, the journey matters as much [as] the arrival’. My own research on the Carment and Inglis families’ histories represents one such journey that began about half a century ago. As a boy in Sydney, I was curious about my mainly Scottish ancestry and asked my parents and other relations about it. Although I was Australian-born and never travelled outside Australia until I was an adult, Scottish associations and influences were prominent during my childhood. My Carment and Inglis grandmothers were born in Scotland, while my Carment grandfather received his university education and worked there. Scotland was often mentioned in family conversations. -

Ònurungióremembered OFFICIAL NEWSLETTER of the CONCORD HERITAGE SOCIETY Email: [email protected]

ÒNurungiÓRemembered OFFICIAL NEWSLETTER OF THE CONCORD HERITAGE SOCIETY email: [email protected] www.concordheritage.asn.au EDITOR No.121 June 2006 LOIS MICHEL 9744-8528 PRESIDENT Metropolitan Fire Brigade JANN OGDEN 9809-5772 The Metropolitan Fire Brigade (MFB), the to easily confirm if the premises were in- precursor to the NSW Fire Brigade, was es- sured and by which company. PUBLIC RELATIONS tablished on 14th February, 1884. TRISH SKEHAN The Companies employed small boys as 4369-4172 MFB headquarters began operating from the runners to notify their brigades of any fires. old Insurance Brigade Headquarters in Upon arrival at the fire the men would in- SECRETARY/TREASURER Bathurst Street but with demand for a new spect the building for the “firemark” to see LOIS MICHEL central fire station the government purchased if the premises were insured by them. If 3 Flavelle Street a site on the western side of Castlereagh not, then they would take no action but (P.O. Box 152) Street and in 1888 the new station was com- probably wouldn’t leave the scene in case Concord 2137 pleted. the fire spread to adjoining buildings which Phone: 9744-8528 might be insured by them. Fax: 9744-7591 From dusk to dawn junior fire fighters spent ----------------- three hours on a twenty metre high tower In 1854 Andrew Torning inaugurated the first MEETINGS (called the pigeon box) undertaking fire spot- Volunteer Fire Brigade in Sydney and also General Meetings ting duty. assisted in the formation of others. 2nd Wednesday of month A watchroom was located on the northern In the days of the Volunteer Fire Brigades, at 7:30 pm in the side of the ground floor and telephone ex- payment was made to the brigade which Concord Citizens’ Centre 9 Wellbank Street, Concord change board, fire alarms and electrical ap- discharged the first stream of water on the Phone: 8765-9155 paratus were operated from there. -

File Organization

RESEARCH FILE INDEX Updated December 2016 Welcome to the Anacortes Museum’s index to the contents of our extensive research files. These files were created by Terry Slotemaker, with the assistance of others on the museum staff, during his (second) career as the Anacortes Museum Educator between 1994 and 2011. The files consist of newspaper and magazine articles, directory listings, and unique research done by Terry and other historians. Thankfully, even after retirement, Terry’s work continues to this day. To search this pdf document, use “Find” and enter a search word. AGRICULTURE ALSO SEE: BIA Livery Stables, BI Kelp Processors Ag Agriculture Survey 1954 Ag Beef Farming Ag Berry Farming, Fidalgo and Guemes Islands Ag Berry Farming, Skagit Valley (Also see: PSV Sakuma Family) Ag Cabbage, Cauliflower Ag Clearing the Land Ag Dairy Farming (Also see: BI Dairies/Creameries) Ag Farming, Fidalgo and Guemes Islands Ag Farm Machinery Ag Fruit Orchards Ag Fur Farming, Fox, Mink Ag Gardening Ag Ginseng and Golden Seal Farming Ag Grain Crops Ag Hop Farms Ag Potato Farming Ag Poultry Farming Ag Seed Growers, Skagit Valley Ag Sheep Farming Ag Skagit Valley Farming Ag Tulip Farming, Skagit Valley Ag Vegetable Farms/Gardens (Also see: PFG Folmer, W.G.; Mellena, M.K.) ANIMALS See: Fa FAUNA 2 ARTS, CRAFTS, MUSIC (MONUMENTS, MURALS, PAINTINGS, NEEDLEWORK, ETC.) Anacortes Community Theater: See OG Anacortes Arts and Crafts Festival: See EV Art ACM Aerie (roundabout sculpture) Highway 20 and Commercial Ave. (Also see: BS Gateways) * Anacortes Community -

Attachment B

Attachment B Eora Journey – Harbour Walk Historical Research Historical Research Materials Eora Journey – Harbour Walk March 2019 This collection of historical writings was produced by Dr Paul Irish of Coast History and Heritage for the Harbour Walk project between December 2018 and March 2019. The items were researched to address specific questions from the project curator, or to provide context and broad themes, and did not involve exhaustive research on any topic. Research was archival only, and did not include consultation with Aboriginal people who may hold knowledge about particular places or subjects. Many of the items included have recommendations about further potential sources of information. If specific projects are developed to implement the Harbour Walk, these and other sources are likely to provide further details that may be useful. A copy of these writings will also be deposited in the City of Sydney Archives, so that it can be accessed by future researchers. WARNING: Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander readers should note that this document contains images of deceased Aboriginal people. ACN 625 442 480 / P: (61 2) 9599 7449 / E: [email protected] / W: www.coasthistory.com.au / PO Box A74 Arncliffe NSW 2205 Historical Research Materials Eora Journey – Harbour Walk Table of Contents 1 The Original Shoreline 3 2 Historical Views along the Harbour Walk 5 3 Water Connections 23 4 Aboriginal Wharf Workers 29 5 Jack Stewart 38 6 Shellwork in the City 40 7 The Domain and Woolloomooloo 47 8 Bungaree and Garden Island 56 9 References 58 2 Historical Research Materials Eora Journey – Harbour Walk 1 The Original Shoreline The following maps are approximations of the 1788 shoreline in relation to today. -

Sea Dumping in Australia: Historical and Contemporary Aspects

Historical and Contemporary Aspects 2003 © Commonwealth of Australia 2003 Department of Defence, Australia Department of the Environment and Heritage, Australia This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Department of Defence and the Department of the Environment and Heritage. Sea dumping in Australia : historical and contemporary aspects First edition, — This edition. First published by the Department of Defence, Australia 2003 Publisher Defence Publishing Service Department of Defence CANBERRA ACT 2600 National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Plunkett, Geoff. Sea dumping in Australia : historical and contemporary aspects. Bibliography. Includes index. ISBN 0 642 29588 3. 1. Waste disposal in the ocean - Australia. 2. Marine resources conservation - Australia. I. Australia. Dept. of Defence. II. Australia. Dept. of the Environment and Heritage. III. Title. 363.7280994 Full cataloguing available on the National Library of Australia web site http://www.nla.gov.au Sea Dumping in Australia: Historical and Contemporary Aspects Geoff Plunkett This report brings together a number of studies undertaken on all aspects of Sea Dumping in Australia and it Territories. These were previously available in a number of disparate sources and have been collated here for convenience. At date of publication (2003), Sea Dumping in Australian waters is managed by the Department of the Environment and Heritage, Canberra. -

Baragoola Week Ending 11Th September ‘11

Baragoola Week Ending 11th September ‘11 In attendance: Geoff, Nick, Glen, Lance, Gary, Ernie, Peter H, Peter C, Chris and David Visitors: Three Don’t forget – we have chocolates waiting to be sold! If you can help by putting a box in your workplace give me a yell and we’ll get some to you. Don’t forget that all donations over $2 are now tax deductible – why not do what some of our donors have and set up an automatic payment once a week, fortnight or month ? Coming up: The BPA will be at Manly Corso on Saturday the 17th of September. We’ll be at our usual spot under the fig tree opposite the news agents – thanks to Manly Council for the venue. More items for sale have been ordered for this event. One week after we’ll be holding another open day on board the boat; we’ve distributed the flyer to all members and have already received promises from several to put these up in local shopping centres and on community notice boards – get the message out as far and as wide as possible! We are already getting bookings for what promises to be a busy day for us. These are always good for us – from a PR perspective, new member and volunteer perspective and of course we also do well with donations – so please spread the word as far and wide as possible and help us make this one a big event. We’re still chasing a fairly hefty fundraising target (you can see it on our main webpage) but are inching closer every week. -

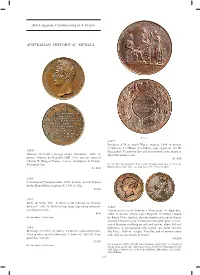

Sixth Session, Commencing at 4.30 Pm AUSTRALIAN HISTORICAL

Sixth Session, Commencing at 4.30 pm AUSTRALIAN HISTORICAL MEDALS Reduced 1559* Products of New South Wales, Sydney, 1854 in bronze (73mm) by L.C.Wyon (C.1854/5), edge engraved, 'Sir W. 1555* Macarthur. ' Extremely fi ne and an extremely rare award to Dumont D'Urville's Voyage of the 'Astrolabe', 1826, in John Macarthur's son. bronze (50mm) by Depaulis (MH 190), obverse, bust of $1,800 Charles X, King of France, reverse, inscription in French. Extremely fi ne. See lot 1561 for biography. This and the following four lots all ex the Sir $1,000 William Macarthur estate. See also lots 2717, 2728 and 3090. 1556 Cessation of Transportation, 1853, in white metal (58mm) by the Royal Mint, London (C.1853/2). Fine. $100 1557 Burke & Wills, 1861, in white metal (38mm) by Thomas Stokes (C.1861/1). Holed at top, large edge bump and poor 1560* condition but rare. Commencement of Volunteer Movement, in Australia, $60 1856, in bronze (33mm) by J.Hogarth (C.1856/1) struck Ex Tom Hanley Collection. by Royal Mint, Sydney, obverse diademed head of Queen Victoria left with legend 'Victoria Dei Gratia Regina', reverse, seated Britannia holding wreath and trident, ships, hill and 1558 lighthouse in background with legend 'Aut Bello Victoria Marriage of Prince of Wales, Victoria's commemoration, Aut Pace', 1856 in exergue. Very fi ne and of utmost rarity 1863 in white metal (34mm) by T. Stokes (C.1863/3). Very with only twelve struck in bronze. good/fi ne and rare. $4,500 $100 As an indicator of its rarity, Dr John Chapman did not have an example of Ex Tom Hanley Collection. -

Baragoola Week Ending 25Th September ‘11

Baragoola Week Ending 25th September ‘11 In attendance: Nick, Gary, Ernie, Lance, Peter C, Peter H, Glenn, Bill, David, Geoff E, Geoff L, Luke and Mark Visitors: Many! Don’t forget that all donations over $2 are now tax deductible – why not do what some of our donors have and set up an automatic payment once a week, fortnight or month ? Coming up: On the 1st of October the boat will again be closed as we will be holding a lunch for all volunteers past and present to say “thank you” for the immense amount of work that has been done so far – a monumental effort has been put in by our dedicated team and Baragoola is certainly looking the better for it – no longer can she be given the derelict tag and she is certainly shaping up to being a gem of the harbour. Volunteers must let me know if you are coming. We’re still chasing a fairly hefty fundraising target (you can see it on our main webpage) but are inching closer every week. With our tax deductible gift status there’s no reason now to hold off on donations! Last week we had outgoings of $0 and we made $500. I haven’t included yesterdays takings as these haven’t been banked yet – they’ll show up in next week’s total. Later this year we are also booked for a BBQ at Bunnings Belrose, we have a couple of our members who have volunteered to assist with this event but still need a further four – if you can assist please let us know.