Perceptions of Masculinities in Japanese Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

The Undead Subject of Lost Decade Japanese Horror Cinema a Thesis

The Undead Subject of Lost Decade Japanese Horror Cinema A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Jordan G. Parrish August 2017 © 2017 Jordan G. Parrish. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled The Undead Subject of Lost Decade Japanese Horror Cinema by JORDAN G. PARRISH has been approved for the Film Division and the College of Fine Arts by Ofer Eliaz Assistant Professor of Film Studies Matthew R. Shaftel Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 Abstract PARRISH, JORDAN G., M.A., August 2017, Film Studies The Undead Subject of Lost Decade Japanese Horror Cinema Director of Thesis: Ofer Eliaz This thesis argues that Japanese Horror films released around the turn of the twenty- first century define a new mode of subjectivity: “undead subjectivity.” Exploring the implications of this concept, this study locates the undead subject’s origins within a Japanese recession, decimated social conditions, and a period outside of historical progression known as the “Lost Decade.” It suggests that the form and content of “J- Horror” films reveal a problematic visual structure haunting the nation in relation to the gaze of a structural father figure. In doing so, this thesis purports that these films interrogate psychoanalytic concepts such as the gaze, the big Other, and the death drive. This study posits themes, philosophies, and formal elements within J-Horror films that place the undead subject within a worldly depiction of the afterlife, the films repeatedly ending on an image of an emptied-out Japan invisible to the big Other’s gaze. -

Practice-Oriented Exercises As One of the Ways to Form the Competences of University Students

International Journal of Environmental & Science Education, 2016, 11(7), 1509-1526 Practice-Oriented Exercises as One of the Ways to Form the Competences of University Students Marina Alexandrovna Romanova, Olga Vladimirovna Shashkina & Elena Viktorovna Starchenko Sakhalin State University, RUSSIA Received 11January 2016 Revised 26 April 2016 Accepted 03 May 2016 The article describes the methods of teaching students majoring in languages with the use of practice-oriented exercises, the need for the development and implementation of which is defined by a new methodological basis of modern higher vocational education – a competence-based approach. The study hypothesis involves the assumption that practice-oriented exercises allow to intensify the mental, practical and creative student activities, form a positive motivation both to study Japanese and be engaged in future professional activities. The article contains the results of the joint work of teachers of the Sakhalin State University on drawing up and introduction of practice-oriented exercises for students studying Japanese at the level of professional communication at the university and majoring in "Oriental and African Studies" and "Pedagogical Education". The study represents the general content of practice-oriented exercises, implying an interdisciplinary impact and integration of training courses, independent work of students, students' clear understanding of the ultimate goals of the task and assessment means. The content of each exercise, the rationale for its development, objectives, targets, the progress and the learning results have been described in detail. Students' comments have been presented demonstrating the efficiency of using practice-oriented exercises in the educational process. Keywords: competences; methods of teaching students; practice-oriented exercises; Japanese language; educational process INTRODUCTION Relevance of the study A competence-based approach described in the works of Bermus A.G., Zimnyaya I.A., Kogan E.Y., Lebedev O.E., etc. -

Tokyo Story (Tokyo Monogatari, Yasujiro Ozu, 1953) Discussion Points 1

FAC@JGC John Gray Centre Star Room April 2016 Tokyo Story (Tokyo monogatari, Yasujiro Ozu, 1953) Discussion Points 1. Think about what is at the core (theme) of the story? 2. How does Ozu depict family dynamics in this film – specifically the bond between parents and children? 3. How do you respond to the slow pace of the film? 4. What is your opinion on the portrayal of women in the narrative? 5. What do you think is the effect of presenting: (a) frames in which the camera is right between the two people conversing and films each person directly? (b) so-called tatami shots (the camera is placed as if it were a person kneeling on a tatami mat)? 1 Dr Hanita Ritchie Twitter: @CineFem FAC@JGC John Gray Centre Star Room April 2016 6. How does Ozu present the progression of time in the story? 7. Think about the following translated dialogue between Kyoko, the youngest daughter in the family, and Noriko, the widowed daughter-in-law, after Mrs Hirayama’s death. How would you interpret it in terms of the story as a whole? K: “I think they should have stayed a bit longer.” N: “But they’re busy.” K: “They’re selfish. Demanding things and leaving like this.” N: “They have their own affairs.” K: “You have yours too. They’re selfish. Wanting her clothes right after her death. I felt so sorry for poor mother. Even strangers would have been more considerate.” N: “But look Kyoko. At your age I thought so too. But children do drift away from their parents. -

Introduction 1 Samurai in Videogames 2 the Cinematic Factor 16 Samurai of Legend 26 Mythification, Immersion and Interactivity 3

INTRODUCTION 1 SAMURAI IN VIDEOGAMES 2 Sword of the Samurai (2003, JP) 2 The W ay of the Samurai (2002, JP) 6 Onimusha W arlords (2001, JP) 8 Throne of Darkness (2001, USA) 11 Shogun: total W ar, the warlord edition (2001, UK) 13 THE CINEMATIC FACTOR 16 The lone swordsman 16 Animé 20 The Seven Samurai 23 The face of the silver screen warrior 24 SAMURAI OF LEGEND 26 Musashi 26 Yagyu Jubei 28 Oda Nobunaga 30 MYTHIFICATION, IMMERSION AND INTERACTIVITY 32 Mythification 32 Immersion, Interactivity and Representation 34 CONCLUSION 39 BIBLIOGRAPHY 41 Introduction The Samurai, everyone has a certain mental image of these warriors, be it the romanticized noble warrior or the ruthless fighter, or even the lone wanderer who is trying to change his fate by the sword. These images of the Samurai are most often based on popular (mediated) productions like the Japanese period film (Jidai Geki) and, most recently, Samurai videogames. It is this last and newest of these mediated productions, the videogame, which will be the main subject of this Thesis. I will start by describing videogames that incorporate these warriors, then I will try to determine if film has had any influence on this representation. From the influence of film I will move on to other contemporary media: the novel, Animé films and Manga comics. It is my goal to determine in what manner all these forms of contemporary media have influenced the representation of the Samurai in videogames. I will use a theory by Desser, which he calls —Mythification of history“. Desser claims in his book, —The Samurai films of Akira Kurosawa“, that the Japanese film has a tendency to elevate certain historical periods, figures, facts and legends into mythic proportions. -

Battle Without Honor and Humanity Synopsis

Battle Without Honor and Humanity Synopsis Synopsis In the teeming black markets of postwar Japan, Shozo Hirono and his buddies find themselves in a new war between factious and ambitious yakuza. After joining boss Yamamori, Shozo is drawn into a feud with his sworn brother’s family, the Dois. But that is where the chivalry ends and the hypocrisy, betrayal, and assassinations begin. 1946-1955: While in jail for killing a yakuza, Shozo Hirono does a favor for Hiroshi Wakasugi, another yakuza belonging to the Doi family. When Shozo is released, he joins his new friends (Sakai, Ueda, Makihara, Yano, Yamagata, Kanbara, Shinkai, and Arita) to form their own family under boss Yoshio Yamamori. By rigging an assembly election, Yamamori crosses Doi and, as a result, Wakasugi leaves the Doi to join his sworn brother Hirono in the Yamamori family. Conversely, Kanbara sells out Yamamori and joins the Doi family. Hirono assassinates Doi for Yamamori and return to jail. Wakasugi kills Kanbara and is in turn killed by the cops after being set up by Yamamori. Meanwhile, an internal conflict between Yamamori and Sakai unfolds over the sale of drugs by Shinkai and Arita. Yamamori has Arita kill Ueda, and Sakai wipes out Shinkai and Yano. Feeling threatened by Sakai’s growing power, Yamamori tries to lure Hirono into killing Sakai, but he balks in hopes of restoring the family. Yamamori uses Yano’s men to assassinate Sakai and succeeds. In disgust, Hirono turns his back on the Yamamori family. Director Kinji Fukasaku Born in Ibaraki Prefecture in 1930, Fukasaku is the director of TOEI’s legendary yakuza series, “Battles Without Honor and Humanity”. -

Kinji Fukasaku, El Cine De La Crueldad.Japan Cult Cinema 19

Kinji Fukasaku, el cine de la crueldad.Japan Cult Cinema 19/29.05.06 Otra forma de ver cine Kinji Fukasaku, el cine de la crueldad.Japan Cult Cinema Viernes 19 20.30h Kinji Fukasaku, el cine de la crueldad (I) Policía contra el crimen organizado (Kenkei tai shoshiki boryoku / Cops v Thugs), de Kinji Fukasaku. Japón, 1975. 100’. V.O.S. en inglés y español electrónico. Sábado 20 20.30 h Kinji Fukasaku, el cine de la crueldad (II) Mafioso callejero (Gendai yakuza: hito-Kiro yota / Street Mobster), de Kinji Fukasaku. Japón, 1972. 92’. V.O.S. en inglés y español electrónico. Domingo 21 20.30h Kinji Fukasaku, el cine de la crueldad (III) Japan organized crime boss - Nihon boryoku- dan: Kumicho, de Kinji Fukasaku .Japon, 1969. 97’. V.O.S. en inglés y español electrónico. Viernes 26 20.30h Kinji Fukasaku, el cine de la crueldad (IV) Simpatía por los perdedores (Bakuto gaijin butai/ Sympathy for the Underdog), de Kinji Fukasaku. Japón, 1971. 93’. V.O.S. en inglés y español electrónico. Sábado 27 20.30 h Kinji Fukasaku, el cine de la crueldad (V) Codicia a la luz del día (Hakuchu no buraikan/ Greed in Broad Daylight), de Kinji Fukasaku. Japón, 1961. 82’. V.O.S. en inglés y español electrónico. Domingo28 20.30 h Kinji Fukasaku, el cine de la crueldad (y VI) Samurai del Shogun (Yagyû ichizoku no inbô/The Shogun's Samurai/ The Yagyu Conspiracy), de Kinji Fukasaku. Japón, 1978. 130’. V.O.S. en inglés y español electrónico. - 2 - Otra forma de ver cine La Cinemateca UGT, Casia Asia y Japan Foundation, presentan el ciclo: Kinji Fukasaku, el cine de la crueldad. -

Reflections of (And On) Otaku and Fujoshi in Anime and Manga

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2014 The Great Mirror of Fandom: Reflections of (and on) Otaku and Fujoshi in Anime and Manga Clarissa Graffeo University of Central Florida Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Graffeo, Clarissa, "The Great Mirror of Fandom: Reflections of (and on) Otaku and ujoshiF in Anime and Manga" (2014). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 4695. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/4695 THE GREAT MIRROR OF FANDOM: REFLECTIONS OF (AND ON) OTAKU AND FUJOSHI IN ANIME AND MANGA by CLARISSA GRAFFEO B.A. University of Central Florida, 2006 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of English in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2014 © 2014 Clarissa Graffeo ii ABSTRACT The focus of this thesis is to examine representations of otaku and fujoshi (i.e., dedicated fans of pop culture) in Japanese anime and manga from 1991 until the present. I analyze how these fictional images of fans participate in larger mass media and academic discourses about otaku and fujoshi, and how even self-produced reflections of fan identity are defined by the combination of larger normative discourses and market demands. -

The Yakuza Movie Book

THE YAKUZA MOVIE BOOK A GUIDE TO JAPANESE GANGSTER FILMS MARK SCHILLING STONE BRIDGE PRESS • BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA CONTENTS 11 Foreword 126 Akira Kobayashi (1937-) 127 HirokiMatsukata(1942-) INTRODUCTION 128 JoShishido(1933-) 19 A Brief History of Japanese Yakuza Films 130 BuntaSugawara(1933-) Bunta Sugawara Interview 132 DIRECTOR PROFILES & INTERVIEWS 143 KenTakakura(1931-) 43 Kinji Fukasaku (1930-2003) 145 Riki Takeuchi (1964-) Kinji Fukasaku Interview 46 146 Koji Tsuruta (1924-87) 55 Teruolshii(1924-) 148 Tatsuo Umemiya (1938-) Term Isbii Interview 51 149 Tomisaburo Wakayama (1929-92) 70 Tai Kato (1916-85) 150 Tetsuya Watari (1941-) 73 Takeshi Kitano ("Beat" Takeshi; 1947-) 76 TakashiMiike(1960-) FILM REVIEWS Takashi Miike Interview 78 155 AHomansu(l986) 85 RokuroMochizuki(1957-) Rokuro Mochizuki Interview 87 156 Abashiri Bangaicbi (A Man from Abashiri Prison, 1965) 95 Seijun Suzuki (1923-) Seijun Suzuki Interview 98 156 Abashiri Bangaicbi: Bokyohen (A Man from Abashiri Prison: Going Home, 1965) ACTOR PROFILES & INTERVIEWS 157 Adrenaline Drive (1999) 109 ShowAikawa(1961-) Show Aikawa Interview 110 158 Akumyo (Tough Guy, 1961) 119 Noboru Ando (1926-) 159 American Yakuza (1994) Noboru Ando Interview 121 160 Ankokugai no Kaoyaku (The Big Boss, 123 Junko Fuji (1945-) 1959) 125 Shintaro Katsu (1931-97) 161 Asu Naki Machikado (End of Our Own Real, 1997) 162 Bakuchiuchi Socho Tobaku (Big Gambling 193 Gokudo no Onnatachi (Gang Wives, 1986) Ceremony, 1968) 197 Gokudo no Onnatachi: Kejime (Gang 164 Bakuto Gaijin Butai (Sympathy for the Wives: -

Harga Sewaktu Wak Jadi Sebelum

HARGA SEWAKTU WAKTU BISA BERUBAH, HARGA TERBARU DAN STOCK JADI SEBELUM ORDER SILAHKAN HUBUNGI KONTAK UNTUK CEK HARGA YANG TERTERA SUDAH FULL ISI !!!! Berikut harga HDD per tgl 14 - 02 - 2016 : PROMO BERLAKU SELAMA PERSEDIAAN MASIH ADA!!! EXTERNAL NEW MODEL my passport ultra 1tb Rp 1,040,000 NEW MODEL my passport ultra 2tb Rp 1,560,000 NEW MODEL my passport ultra 3tb Rp 2,500,000 NEW wd element 500gb Rp 735,000 1tb Rp 990,000 2tb WD my book Premium Storage 2tb Rp 1,650,000 (external 3,5") 3tb Rp 2,070,000 pakai adaptor 4tb Rp 2,700,000 6tb Rp 4,200,000 WD ELEMENT DESKTOP (NEW MODEL) 2tb 3tb Rp 1,950,000 Seagate falcon desktop (pake adaptor) 2tb Rp 1,500,000 NEW MODEL!! 3tb Rp - 4tb Rp - Hitachi touro Desk PRO 4tb seagate falcon 500gb Rp 715,000 1tb Rp 980,000 2tb Rp 1,510,000 Seagate SLIM 500gb Rp 750,000 1tb Rp 1,000,000 2tb Rp 1,550,000 1tb seagate wireless up 2tb Hitachi touro 500gb Rp 740,000 1tb Rp 930,000 Hitachi touro S 7200rpm 500gb Rp 810,000 1tb Rp 1,050,000 Transcend 500gb Anti shock 25H3 1tb Rp 1,040,000 2tb Rp 1,725,000 ADATA HD 710 750gb antishock & Waterproof 1tb Rp 1,000,000 2tb INTERNAL WD Blue 500gb Rp 710,000 1tb Rp 840,000 green 2tb Rp 1,270,000 3tb Rp 1,715,000 4tb Rp 2,400,000 5tb Rp 2,960,000 6tb Rp 3,840,000 black 500gb Rp 1,025,000 1tb Rp 1,285,000 2tb Rp 2,055,000 3tb Rp 2,680,000 4tb Rp 3,460,000 SEAGATE Internal 500gb Rp 685,000 1tb Rp 835,000 2tb Rp 1,215,000 3tb Rp 1,655,000 4tb Rp 2,370,000 Hitachi internal 500gb 1tb Toshiba internal 500gb Rp 630,000 1tb 2tb Rp 1,155,000 3tb Rp 1,585,000 untuk yang ingin -

Language Lab Video Catalog

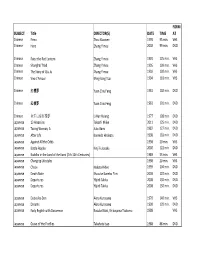

FORM SUBJECT Title DIRECTOR(S) DATE TIME AT Chinese Ermo Zhou Xiaowen 1995 95 min. VHS Chinese Hero Zhang Yimou 2002 99 min. DVD Chinese Raise the Red Lantern Zhang Yimou 1991 125 min. VHS Chinese Shanghai Triad Zhang Yimou 1995 109 min. VHS Chinese The Story of Qiu Ju Zhang Yimou 1992 100 min. VHS Chinese Vive L'Amour Ming‐liang Tsai 1994 118 min. VHS Chinese 紅樓夢 Yuan Chiu Feng 1961 102 min. DVD Chinese 紅樓夢 Yuan Chiu Feng 1961 101 min. DVD Chinese 金玉良緣紅樓夢 Li Han Hsiang 1977 108 min. DVD Japanese 13 Assassins Takashi Miike 2011 125 min. DVD Japanese Taxing Woman, AJuzo Itami 1987 127 min. DVD Japanese After Life Koreeda Hirokazu 1998 118 min. DVD Japanese Against All the Odds 1998 20 min. VHS Japanese Battle Royale Kinji Fukasaku 2000 122 min. DVD Japanese Buddha in the Land of the Kami (7th‐12th Centuries) 1989 53 min. VHS Japanese Changing Lifestyles 1998 20 min. VHS Japanese Chaos Nakata Hideo 1999 104 min. DVD Japanese Death Note Shusuke Kaneko Film 2003 120 min. DVD Japanese Departures Yôjirô Takita 2008 130 min. DVD Japanese Departures Yôjirô Takita 2008 130 min. DVD Japanese Dodes'ka‐Den Akira Kurosawa 1970 140 min. VHS Japanese Dreams Akira Kurosawa 1990 120 min. DVD Japanese Early English with Doraemon Kusuba Kôzô, Shibayama Tsutomu 1988 VHS Japanese Grave of the Fireflies Takahata Isao 1988 88 min. DVD FORM SUBJECT Title DIRECTOR(S) DATE TIME AT Japanese Happiness of the Katakuris Takashi Miike 2001 113 min. DVD Japanese Ikiru Akira Kurosawa 1952 143 min. -

Anime/Games/J-Pop/J-Rock/Vocaloid

Anime/Games/J-Pop/J-Rock/Vocaloid Deutsch Alice Im Wunderland Opening Anne mit den roten Haaren Opening Attack On Titans So Ist Es Immer Beyblade Opening Biene Maja Opening Catpain Harlock Opening Card Captor Sakura Ending Chibi Maruko-Chan Opening Cutie Honey Opening Detektiv Conan OP 7 - Die Zeit steht still Detektiv Conan OP 8 - Ich Kann Nichts Dagegen Tun Detektiv Conan Opening 1 - 100 Jahre Geh'n Vorbei Detektiv Conan Opening 2 - Laufe Durch Die Zeit Detektiv Conan Opening 3 - Mit Aller Kraft Detektiv Conan Opening 4 - Mein Geheimnis Detektiv Conan Opening 5 - Die Liebe Kann Nicht Warten Die Tollen Fussball-Stars (Tsubasa) Opening Digimon Adventure Opening - Leb' Deinen Traum Digimon Adventure Opening - Leb' Deinen Traum (Instrumental) Digimon Adventure Wir Werden Siegen (Instrumental) Digimon Adventure 02 Opening - Ich Werde Da Sein Digimon Adventure 02 Opening - Ich Werde Da Sein (Insttrumental) Digimon Frontier Die Hyper Spirit Digitation (Instrumental) Digimon Frontier Opening - Wenn das Feuer In Dir Brennt Digimon Frontier Opening - Wenn das Feuer In Dir Brennt (Instrumental) (Lange Version) Digimon Frontier Wenn Du Willst (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Eine Vision (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Ending - Neuer Morgen Digimon Tamers Neuer Morgen (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Opening - Der Grösste Träumer Digimon Tamers Opening - Der Grösste Träumer (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Regenbogen Digimon Tamers Regenbogen (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Sei Frei (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Spiel Dein Spiel (Instrumental) DoReMi Ending Doremi