Bulletin 22Nd March 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St. Enda Catholic.Net

St. Enda Catholic.net Early life and conversion According to the Martyrdom of Oengus, Enda was an Irish prince, son of Conall Derg of Oriel (Ergall) in Ulster. Legend has it that when his father died, he succeeded him as king and went off to fight his enemies. The soldier Enda was converted by his sister, Saint Fanchea, an abbess. He visited Fanchea, who tried to persuade him to lay down his arms. He agreed, if only she would give him a young girl in the convent for a wife. He renounced his dreams of conquest and decided to marry. The girl she promised turned out to have just died, and Fanchea forced him to view the girl's corpse, to teach him that he, too, would face death and judgment. Faced with the reality of death, and by his sister's persuasion, Enda decided to study for the priesthood, and studied first at St Ailbe’s monastery at Emly. Fanchea sent him to Candida Casa in southwestern Scotland, a great center of monasticism. There he took monastic vows and was ordained. The stories told of the early life of Saint Enda and his sister are unhistorical. More authentic vitae survive at Tighlaghearny at Inishmore, where he was buried. The Monastic School of Aran It is said that Enda learned the principles of monastic life at Rosnat in Britain. Returning to Ireland, Enda built a church at Drogheda. About 484 he was given land in the Aran Islands by his brother-in-law, Aengus, King of Munster. Three limestone islands make up the Aran Islands: Inishmore, Inishmaan and Inisheer (respectively, the Great, Central and Eastern Island). -

Religious Studies

RELIGIOUS STUDIES Religious Studies The Celtic Church in Ireland in the Fifth, Sixth and Seventh Centuries Unit AS 5 Content/Specification Section Page The Arrival of Christianity in Ireland 2 Evidence for the presence of Christianity in Ireland before the arrival of St. Patrick 6 Celtic Monasticism 11 Celtic Penitentials 17 Celtic Hagiography 21 Other Aspects of Human Experience Section 25 Glossary 42 RELIGIOUS STUDIES The Arrival of Christianity in Ireland © LindaMarieCaldwell/iStock/iStock/Thinkstock.com Learning Objective – demonstrate knowledge and understanding of, and critically evaluate the background to the arrival of Christianity in Ireland, including: • The political, social and religious background; • The arrival of and the evidence for Christianity in Ireland before Patrick; and • The significance of references to Palladius. This section requires students to explore: 1. The political, social and religious background in Ireland prior to the arrival of Christianity in Ireland. 2. Evidence of the arrival of Christianity in Ireland before Patrick (Pre-Patrician Christianity. 3. References to Palladius and the significance of these references to understanding the background to Christianity in Ireland before Patrick’s arrival. Early Irish society provided a great contrast to the society of the Roman Empire. For example, it had no towns or cities, no central government or no standard currency. Many Scholars have described it as tribal, rural, hierarchical and familiar. The Tuath was the basic political group or unit and was a piece of territory ruled by a King. It is estimated that there were about 150 such Tuath in pre – Christian Ireland. The basic social group was the fine and included all relations in the male line of descent. -

The Annals of the Four Masters De Búrca Rare Books Download

De Búrca Rare Books A selection of fine, rare and important books and manuscripts Catalogue 142 Summer 2020 DE BÚRCA RARE BOOKS Cloonagashel, 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. 01 288 2159 01 288 6960 CATALOGUE 142 Summer 2020 PLEASE NOTE 1. Please order by item number: Four Masters is the code word for this catalogue which means: “Please forward from Catalogue 142: item/s ...”. 2. Payment strictly on receipt of books. 3. You may return any item found unsatisfactory, within seven days. 4. All items are in good condition, octavo, and cloth bound, unless otherwise stated. 5. Prices are net and in Euro. Other currencies are accepted. 6. Postage, insurance and packaging are extra. 7. All enquiries/orders will be answered. 8. We are open to visitors, preferably by appointment. 9. Our hours of business are: Mon. to Fri. 9 a.m.-5.30 p.m., Sat. 10 a.m.- 1 p.m. 10. As we are Specialists in Fine Books, Manuscripts and Maps relating to Ireland, we are always interested in acquiring same, and pay the best prices. 11. We accept: Visa and Mastercard. There is an administration charge of 2.5% on all credit cards. 12. All books etc. remain our property until paid for. 13. Text and images copyright © De Burca Rare Books. 14. All correspondence to 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. Telephone (01) 288 2159. International + 353 1 288 2159 (01) 288 6960. International + 353 1 288 6960 Fax (01) 283 4080. International + 353 1 283 4080 e-mail [email protected] web site www.deburcararebooks.com COVER ILLUSTRATIONS: Our cover illustration is taken from item 70, Owen Connellan’s translation of The Annals of the Four Masters. -

The Churches of County Clare, and the Origin of the Ecclesiastical Divisions in That County Author(S): T

The Churches of County Clare, and the Origin of the Ecclesiastical Divisions in That County Author(s): T. J. Westropp Source: Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy (1889-1901), Vol. 6 (1900 - 1902), pp. 100-180 Published by: Royal Irish Academy Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20488773 . Accessed: 07/08/2013 21:49 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Royal Irish Academy is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy (1889-1901). http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 140.203.12.206 on Wed, 7 Aug 2013 21:49:12 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions [ 100 ] THE CHURCHES OF COUNTY CLARE, AND THE ORIGIN OF THE ECCLESIASTICAL DIVISIONS IN THAT COUNTY. By T. J. WESTROPP, M.A. (PL&TESVIII. TOXIII.) [Read JUm 25rn, 1900.3 IN laying before this Academy an attempted survey of the ancient churches of a single county, it is hoped that the want of such raw material for any solid work on the ecclesiology of Ireland may justify the publication, and excuse the deficiencies, of the present essay. -

The Origin of the Curvilinear Plan-Form in Irish Ecclesiastical Sites: a Comparative Analysis of Sites in Ireland, Wales and France

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Doctoral Science 2009-10-01 The Origin of the Curvilinear Plan-Form in Irish Ecclesiastical Sites: A Comparative Analysis of Sites in Ireland, Wales and France Clare Crowley Technological University Dublin Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/sciendoc Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Crowley, Clare. (2009). The Origin of the Curvilinear Plan-Form in Irish Ecclesiastical Sites: A Comparative Analysis of Sites in Ireland, Wales and France. Technological University Dublin. doi:10.21427/D7N304 This Theses, Ph.D is brought to you for free and open access by the Science at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License THE ORIGINS OF THE CURVILINEAR PLAN-FORM IN IRISH ECCLESIASTICAL SITES: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF SITES IN IRELAND, i .• WALES AND FRANCE (VOLUME 112) SUBMITTED BY CLARE CROWLEY B.A. (HONS) To SCHOOL OF FOOD SCIENCE AND ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH AT DUBLIN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY FOR THE AWARD OF PHD. SUPERVISOR: DR PAT DARGAN OCTOBER 2009 DECLARATION I certify that this thesis which I now submit for examination for the award of PhD, is entirely my own work and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. This thesis was prepared according to the regulations for postgraduate studies by research of the Dublin Institute of Technology and has not been submitted in whole or in part for an award in any other Institute or University. -

Craig Haggart

The cili De and ecclesiasticalgovemment in Ireland in the eighth and ninth centuries. Craig Haggart Submitted for the degreeof Ph.D. in the Department of Celtic, University of Glasgow, March 2003. C Craig Haggart 2003 Abstract This thesisexamines the CjU Dj, individual ecclesiasticswho constitutedthe intellectualand spiritualelite in the early medievalIrish church.The period covered by the thesisis restrictedto A.D. 700-900and focussesmost fully on the late eighth and early ninth centuries.A distinction is drawn betweenthose individuals referred to as cili Dj during this period under study and those 'communities within communities',concerned for the welfareof the sick and the poor, to whom the name is later attested.The thesisexamines the primary sourcematerial, considers past and presenttheories regarding these ecclesiastics and refutes the consensusof opinion that the c8i Dj were a reform movementwho emergedin reactionto a degenerate clergy in a church under secularinfluence. It discusseswhat was intendedby the designationcili Dj and proffersthe opinion that the c8i Dj were insteadconcerned with advancingall aspectsof the dutiesand responsibilitiesof the church.Particular developmentsin ecclesiasticalorganisation during the period under study are discussedand the extentof the role of individual cile Dj in theseare examined,but will concludethat it shouldnot be assumedthat thesedevelopments, or concernfor their introduction,was wholly restrictedto the cili De. Therewas a changein the basisof the sourceof royal authority from popular to -

Doolin: History and Memories

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Books / Book chapters School of Hospitality Management and Tourism 2020 Doolin: History and Memories Kevin M. Griffin Independent Scholar Kevin A. Griffin Technological University Dublin, [email protected] Brendan J. Griffin Independent Scholar Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/tfschhmtbook Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Griffin, K.M, Griffin, K.A. & Griffin, B.J. (2020) Doolin: History and Memories. Dublin: Technological University Dublin. doi:10.21427/vbbp-kv37 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Hospitality Management and Tourism at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books / Book chapters by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License Doolin: History & Memories By Kevin M. Griffin with Kevin A. Griffin & Brendan J. Griffin Ballina, Killaloe Print, 2020 i Copyright © 2020 Kevin M. Griffin & Kevin A. Griffin. All rights reserved Published in Ireland by: Ballina Killaloe Print Ballina Killaloe Co. Tipperary [email protected] ISBN Print Version: 978-0-9539320-4-7 Digital Version: 978-0-9539320-3-0 Open Access digital version available online at https://arrow.tudublin.ie/tfschhmtbook/51/ doi:10.21427/vbbp-kv37 Design and Typesetting Kevin M. Griffin & Kevin A. Griffin Cover Photograph by Robert A. Griffin ii Some Notes on Copyright Where possible we have endeavoured to identify intellectual ownership of material throughout this book, in terms of maps, images and text. -

Rathmichael Historical Record 2003

RATHMICHAEL HISTORICAL RECORD 2003 Editor: Del Sherriff Assisted by Rosemary Beckett. Rathmichael Historical Record 2003 Published by Rathmichael Society, 2006 2 CONTENTS Secretary’s Report 2003 5 The National Archives-Aideen Ireland 7 Brugh na Boinne-Dr. Geraldine Stout. 10 Visit to the National Archive 11 Maria Edgeworth, Marie O’Neill. 12 36, Fitzwilliam Square outing. 15 The Secret in Dublin’s Place names - Catherine Scuffil. 18 Spring Weekend 4th/6th April—Carlingford. 24 25 Eustace Street, Dublin outing. 26 Battle of the Boyne, outing. 28 Lambay Island, outing .first & second 30 29th Summer School Evening lectures 30 Irish Soldiers in the Napoleonic Wars - Damian Shiels. 43 Robert Emmett, the Making of a Hero-Dr. P.Geoghegan. 45 Upstairs-Downstairs in Foxrock 100 years ago- D Donnelly.. 48 3 4 THE SECRETARY’S REPORT The year 2003 was very successful and busy for the Society. We are very pleased to report that our membership which at this time last year numbered 80, now numbers 114. After last year’s AGM the committee was fortunate to be able to co-opt two new members: James Byrne and Ms. Frances Collins. James Byrne agreed to act as Hon. Treasurer, but as the search for a new Hon. Secretary was unsuccessful, the President agreed to fulfil this position for the time being. A complete list of Committee members for 2003 is attached to this report., The Society’s activities during 2003 were varied and included: In January, Aideen Ireland gave us a talk about the workings of the National Archive; in February, Dr. -

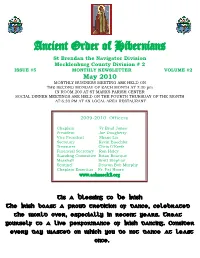

Ancient Order of Hibernians

Ancient Order of Hibernians St Brendan the Navigator Division Mecklenburg County Division # 2 ISSUE #5 MONTHLY NEWSLETTER VOLUME #2 May 2010 MONTHLY BUSINESS MEETING ARE HELD ON THE SECOND MONDAY OF EACH MONTH AT 7:30 pm IN ROOM 200 AT ST MARKS PARISH CENTER SOCIAL DINNER MEETINGS ARE HELD ON THE FOURTH THURSDAY OF THE MONTH AT 6:30 PM AT AN LOCAL AREA RESTAURANT 2009-2010 Officers Chaplain Fr Brad Jones President Joe Dougherty Vice President Shane Lis Secretary Kevin Buechler Treasurer Chris O’Keefe Financial Secretary Ron Haley Standing Committee Brian Bourque Marshall Scott Stephan Sentinel Deacon Bob Murphy Chaplain Emeritus Fr. Pat Hoare www.aohmeck2.org PRESIDENT’S REPORT Brothers, On Thursday, April 22nd, the St Brendan division celebrated its one year anniversary at Bucci’s Italian restaurant in Davidson. We also honored our “Hibernian of the Year”, brother Ray FitzGerald. We had 26 brothers, spouses and children in attendance. It was, by far, the largest group we had at one of our socials and I wish to thank each of the brothers and families that helped us in honoring brother Ray. Nancy and I thought the food and service were excellent and our thanks go out to Mario Bucci and his family for hosting the division, on this very important day. Brothers of the St Brendan division were in attendance to show their support at the installation of the LAOH division here in Huntersville on April 15th. All the sisters of the new division took their pledge including some wives of AOH members. This last Saturday, I was in Greensboro, NC for the quarterly NC State Board meeting and gave a report as the St Brendan division President and also as the State Organizer. -

Faith & Reason

FAITH & REASON THE JOURNAL OF CHRISTENDOM COLLEGE 1999-2000 | Vol. XXIV-XXV “Rude and Religious Irish”: The Cult of Wandering Saints in the Middle Ages Dermot Quinn N 1183 A WELSHMAN CALLED GERALD GIRALDUS CAMBRENSIS TRAVELED TO Ireland. A scholar in a family of soldiers, he came to see for himself “the primitive origin” of the Irish race; to investigate “the popular rumors of the land” so that he might understand a strange and irrational people. Giraldus’s mission was not disinterested. He came to vindicate the Anglo-Norman invasion that had occurred fourteen years before; to show that Irish wretchedness needed English reform. His fndings justifed the journey. The people were indeed backward. They had “little use for the money-making of towns.” They were lazy: “the greatest pleasure is not to work and the greatest wealth is to enjoy liberty.” As for religion, they seemed incorrigibly attached to aboriginal forms. Con- sider their saints. If objects of devotion merely objectify the desires of the devout, then Irish holy men and women were like the Irish themselves: sour, bad-tempered, vindictive and crude: It appears to me very remarkable, [Giraldus wrote] and deserving of notice, that as in the pres- ent life of the people of this nation are beyond all others irascible and prompt to revenge, so also in the life that is after death, the saints of this country, exalted by their merits above those of other lands, appear to be of a vindictive temper. There appears to me to be no other way of accounting for this circumstance but this: As -

The Relic Cult of St Patrick Between the Seventh and the Late Twelfth Centuries in Its European Contexts: a Focus on the Lives

Erskine, Sarah Christine (2012) The relic cult of St Patrick between the seventh and the late twelfth centuries in its European contexts: A focus on the lives. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/3398/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] The Relic Cult of St Patrick between the Seventh and the Late Twelfth Centuries in its European Contexts: A Focus on the Lives By Sarah Christine Erskine MA (Hons), MLitt A thesis presented to the University of Glasgow, School of Humanities, College of Arts. In fulfilment of the thesis requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Celtic Civilisation and History. December 2011 © Sarah Christine Erskine ii Acknowledgements I respectfully extend the first of these acknowledgements to my supervisors at Glasgow University, Professor Thomas Owen Clancy and Dr Marilyn Dunn. Thomas, ‘my Gaffer’, has loyally supported me in my intellectual pursuits and has offered invaluable advice whenever needed: I remain wholeheartedly grateful and proud to have learned so much from such a formidable and respected scholar. -

Brendaniana1895.Pdf

32101 071956260 3435 .7 1895 i I* J ! DKM <)'. '. SECONU >.:;. -fi '>. ' : : i - ' . ' - iIAl %o'i^\)->"3."'- L <.'.,'< BRENDANIANA : ST. BRENDAN THE VOYAGER 5torp BY THE REV. DENIS O'DONOGHUE, M.R.I.A. P.P., ARDFERT SECOND EDITION ON BACK OF WHALE. DUBLIN : BROWNE &. NOLAN, LTD. 34 & 25 NASSAU 1895- STREET . Printed by BKOWNE & NOLAN, LTD., Dul/ltn. PKEFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION. N publishing a Second Edition of my Book on St. Brendan, I wish to express my grateful appreciation of the very idly and favourable manner in which the First Edition 9 received, as far as I have observed, by its readers, and -the many notices of it that have appeared in the Press, ch in Ireland and America, which were uniformly kind d encouraging. Indeed, with respect to the criticism of ;. little volume, I may well say -.—Funes ceciderunt mihi praeclaris — " The lines have fallen unto me in goodly ices. ' I beg to thank Mr. W. A. Cadbury, of Birmingham, for pies of two ancient Maps he kindly sent to me, which .ow the Isle of St. Brendan and the Isle of Hy-Brazil, in e Western Ocean. I have had copies made on a reduced ile of one of these Maps, which was drawn in A.D. 1581, ! the famous geographer, Abraham Ortelius, of Antwerp, 'd they will be found at page 304, where they may serve illustrate the interesting Legends of the Isle of St. Brendan i of Hy-Brazil, which precede that page. /\ 1 DENIS O'DoNOGHUE, P.P., M.E.I. A. I ^ ST.