Are We Still Rolling?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

John Lennon from ‘Imagine’ to Martyrdom Paul Mccartney Wings – Band on the Run George Harrison All Things Must Pass Ringo Starr the Boogaloo Beatle

THE YEARS 1970 -19 8 0 John Lennon From ‘Imagine’ to martyrdom Paul McCartney Wings – band on the run George Harrison All things must pass Ringo Starr The boogaloo Beatle The genuine article VOLUME 2 ISSUE 3 UK £5.99 Packed with classic interviews, reviews and photos from the archives of NME and Melody Maker www.jackdaniels.com ©2005 Jack Daniel’s. All Rights Reserved. JACK DANIEL’S and OLD NO. 7 are registered trademarks. A fine sippin’ whiskey is best enjoyed responsibly. by Billy Preston t’s hard to believe it’s been over sent word for me to come by, we got to – all I remember was we had a groove going and 40 years since I fi rst met The jamming and one thing led to another and someone said “take a solo”, then when the album Beatles in Hamburg in 1962. I ended up recording in the studio with came out my name was there on the song. Plenty I arrived to do a two-week them. The press called me the Fifth Beatle of other musicians worked with them at that time, residency at the Star Club with but I was just really happy to be there. people like Eric Clapton, but they chose to give me Little Richard. He was a hero of theirs Things were hard for them then, Brian a credit for which I’m very grateful. so they were in awe and I think they had died and there was a lot of politics I ended up signing to Apple and making were impressed with me too because and money hassles with Apple, but we a couple of albums with them and in turn had I was only 16 and holding down a job got on personality-wise and they grew to the opportunity to work on their solo albums. -

Nagy Rock 'N' Roll Könyv

Szakács Gábor Nagy rock ʼnʼ roll könyv Szakács Gábor „Ahogy SzakácsSzakács GáborGábor mondjamondja aa műfajábanműfajában egyedülegyedülálló álló Nagy rock’n’rollOzzy Osbourne: c. könyvében: …el kell döntenünk, hogy zajt vagy zenét aka- runk„Amikor hallani.” fiam rehabilitációján megismertem a szerek mélységét, és ez hasonló a heroinhoz, teljesen ledöbbentem.Juhász Kristóf: 55 éves Magyar vagyok Idők és 2017/3/7.hátralé- vô életemben újra kell gondolnom sok mindent, mivel saját magamat is hihetetlenül hosszú ideig károsítottam.” Ozzy Osbourne: „Amikor fiam rehabilitációján megismertem a szerek mélységét, és ez hasonló a heroinhoz, teljesen ledöbbentem. 55 éves vagyok és hátralévő életemben újra kell gondolnom sok mindent, mivel saját magamat is hihetetlenül hosszú ideig károsítottam.” A szerző külünköszönetet köszönetet mond mondaz Attila az ifjúságaAttila ifjúsága lemez zenészeinek:zenészeinek: Kecskés együttes: L. Kecskés András, Kecskés Péter, Herczegh László, Lévai Péter, Nagyné Bartha Anna ifjúifj.© Szakács CsoóriCsoóri Gábor, SándorLászló 2004. június Rock:ISBN Bernáth 963 216 329Tibor, X Berkes Károly, Bóta Zsolt, Horváth János, Hor- váth Menyhért, Papp Gyula, Sárdy Barbara, Szász Ferenc A szerző köszönetet mond Valkóczi Józsefnek a könyv javításáért. © Szakács Gábor, 2004. június, 2021 ISBN© Szakács 963 216Gábor, 329 2004. X június, 2021. február ISBN 963 216 329 X FOTÓK: Antal Orsolya, Ágg Károly, Becskereki Dusi, Dávid Zsolt, Galambos Anita, Knapp Zoltán, Rásonyi Mária, Tóth Tibor BORÍTÓTERV, KÉPFELDOLGOZÁS: FortekFartek Zsolt KIADVÁNYSZERKESZTÔ: Székely-Magyari Hunor KIADÓ ÉS NYOMDA: Holoprint Kft. • 1163 Bp., Veres Péter út 37. Tel.: 403-4470, fax: 402-0229, www.holoprint.hu Nagy Rock ʼnʼ Roll Könyv Tartalomjegyzék Elôszó . 4 Így kezdôdött . 6 Írók, költôk, hangadók . 15 Családok, gyermekek, utódok . 24 Indulás, feltûnés, beérkezés . -

Blackmoore Free

FREE BLACKMOORE PDF Julianne Donaldson | 304 pages | 10 Sep 2013 | Shadow Mountain | 9781609074609 | English | United States Ritchie Blackmore - Wikipedia Richard Hugh Blackmore born 14 April is an English guitarist and songwriter. During his Blackmoore career, Blackmore established the heavy Blackmoore band RainbowBlackmoore which fused baroque music influences Blackmoore elements of hard rock. The family moved to HestonMiddlesexwhen Blackmore was two. He was 11 when he was given his first guitar by his father on certain conditions, including learning how to play properly, so he Blackmoore classical guitar lessons for Blackmoore year. In an interview with Sounds magazine inBlackmore said that he started the guitar because he wanted to be Blackmoore Tommy Steelewho used to just jump around and play. Blackmore loathed school and hated his teachers. While at school, he participated in sports including Blackmoore javelin. Blackmore left school at age 15 and started work as an apprentice radio mechanic at nearby Heathrow Airport. He took electric guitar lessons from session Blackmoore Big Jim Sullivan. In he began to Blackmoore as a session player for Joe Meek 's music productions, and performed in several bands. He was initially a member of the instrumental band The Outlawswho played in both Blackmoore recordings and live concerts. Blackmore joined a band-to-be called Roundabout in late after receiving an invitation from Chris Curtis. Curtis originated the concept of the band, but would be forced out before the band fully formed. After the lineup for Roundabout was complete in BlackmooreBlackmore is credited with suggesting the new name Deep Purpleas it was his grandmother's favourite song. -

Dec. 22, 2015 Snd. Tech. Album Arch

SOUND TECHNIQUES RECORDING ARCHIVE (Albums recorded and mixed complete as well as partial mixes and overdubs where noted) Affinity-Affinity S=Trident Studio SOHO, London. (TRACKED AND MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) R=1970 (Vertigo) E=Frank Owen, Robin Geoffrey Cable P=John Anthony SOURCE=Ken Scott, Discogs, Original Album Liner Notes Albion Country Band-Battle of The Field S=Sound Techniques Studio Chelsea, London. (TRACKED AND MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) S=Island Studio, St. Peter’s Square, London (PARTIAL TRACKING) R=1973 (Carthage) E=John Wood P=John Wood SOURCE: Original Album liner notes/Discogs Albion Dance Band-The Prospect Before Us S=Sound Techniques Studio Chelsea, London. (PARTIALLY TRACKED. MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) S=Olympic Studio #1 Studio, Barnes, London (PARTIAL TRACKING) R=Mar.1976 Rel. (Harvest) @ Sound Techniques, Olympic: Tracks 2,5,8,9 and 14 E= Victor Gamm !1 SOUND TECHNIQUES RECORDING ARCHIVE (Albums recorded and mixed complete as well as partial mixes and overdubs where noted) P=Ashley Hutchings and Simon Nicol SOURCE: Original Album liner notes/Discogs Alice Cooper-Muscle of Love S=Sunset Sound Recorders Hollywood, CA. Studio #2. (TRACKED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) S=Record Plant, NYC, A&R Studio NY (OVERDUBS AND MIX) R=1973 (Warner Bros) E=Jack Douglas P=Jack Douglas and Jack Richardson SOURCE: Original Album liner notes, Discogs Alquin-The Mountain Queen S= De Lane Lea Studio Wembley, London (TRACKED AND MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) R= 1973 (Polydor) E= Dick Plant P= Derek Lawrence SOURCE: Original Album Liner Notes, Discogs Al Stewart-Zero She Flies S=Sound Techniques Studio Chelsea, London. -

PATTO – the JOHN HALSEY INTERVIEW

PATTO – the JOHN HALSEY INTERVIEW Patto, apart from being one of the finest (purely subjective, of course) bands this country ever produced, were not blessed with good fortune. Forever on the verge of making it really big, they broke up after six years of knocking on the door and finding no-one home. Subsequently, two of their number died while the other two were involved in a terrible car smash which left one with severe physical injuries and the other with severe mental problems. Drummer John Halsey is now the only Patto member who could possible give us an interview. Mike Patto and Ollie Halsall are both gone, while bassist Clive Griffiths apparently doesn't even recall being in a band! Despite bearing the scars of the accident (Halsey walks with a pronounced limp), John was only too pleased to submit to a Terrascopic grilling - an interview which took place in the wonderful Suffolk pub he runs with his wife Elaine. Bancroft and I spent a lovely afternoon and evening with the Halseys, B & B'd in the shadow of a 12th Century church cupboard and returned to London the next morning with one of the most enjoyable interviews either of us has ever done. John Halsey: I started playing drums because two mates who lived in my road in North Finchley (N. London), where I'm from, wanted to form a group. This was years and years ago, 1958, 1959. Want to see the photo? PT: Oh, look at that! 1959! Me, with a microphone inside me guitar that used to go out through me Mum's tape recorder, and if you put 'Record' and 'Play' on together, it'd act like an amplifier. -

4Kq's Number 1'S Weekend July 2019

4KQ’S NUMBER 1’S WEEKEND JULY 2019 TIRED OF TOWING THE LINE ROCKY BURNETTE BILLY - DON'T BE A HERO PAPER LACE GOOD HEART FEARGAL SHARKEY LA LA FLYING CIRCUS UNDERCOVER ANGEL ALAN O'DAY POISON ARROW ABC MY GENERATION THE WHO ROSE GARDEN LYNN ANDERSON HANG ON SLOOPY McCOYS JUMP IN MY CAR TED MULRY GANG SLICE OF HEAVEN DAVE DOBBYN & HERBS COME AND SEE HER EASYBEATS MANDY BARRY MANILOW ABRACADABRA STEVE MILLER BAND PHOTOGRAPH RINGO STARR LONG AS I CAN SEE THE LIGHT CREEDENCE CLEARWATER REVIVAL OUR LIPS ARE SEALED GO GO'S DO YA THINK I'M SEXY ROD STEWART MAKING YOUR MIND UP BUCKS FIZZ THE REAL THING RUSSELL MORRIS AGE OF REASON JOHN FARNHAM SHAKIN' ALL OVER NORMIE ROWE I'M GONNA BE (500 MILES) THE PROCLAIMERS BABY BLUE BADFINGER ROCKABILLY REBEL MAJOR MATCHBOX VIDEO KILLED THE RADIO STAR THE BUGGLES FIVE .10 MAN MASTER'S APPRENTICES ITCHYCOO PARK SMALL FACES KARMA CHAMELEON CULTURE CLUB BABY MAKES HER BLUE JEANS TALK DR HOOK SLIPPING AWAY MAX MERRITT & THE METEORS HELP THE BEATLES DENIM AND LACE MARTY RHONE WHAT CAN I SAY BOZ SCAGGS TOO YOUNG TO BE MARRIED THE HOLLIES FLY TOO HIGH JANIS IAN WALK LIKE A MAN FOUR SEASONS BEN MICHAEL JACKSON DOWN DOWN STATUS QUO ALL NIGHT LONG LIONEL RICHIE SORRY EASYBEATS DON'T PULL YOUR LOVE HAMILTON JOE FRANK & REYNOLDS ASHES TO ASHES DAVID BOWIE SHAKE YOUR BOOTY K.C. & SUNSHINE BAND I DON'T KNOW HOW TO LOVE HELEN REDDY BURNING BRIDGES MIKE CURB CONGREGATION BOHEMIAN RHAPSODY QUEEN CHIRPY CHIRPY CHEEP CHEEP MIDDLE OF THE ROAD SHE LOVES YOU THE BEATLES WHITE ROOM CREAM THE LOOK ROXETTE YOU WEREN'T IN LOVE WITH -

Daughter Album If You Leave M4a Download Download Verschillende Artiesten - British Invasion (2017) Album

daughter album if you leave m4a download Download Verschillende artiesten - British Invasion (2017) Album. 1. It's My Life 2. From the Underworld 3. Bring a Little Lovin' 4. Do Wah Diddy Diddy 5. The Walls Fell Down 6. Summer Nights 7. Tuesday Afternoon 8. A World Without Love 9. Downtown 10. This Strange Effect 11. Homburg 12. Eloise 13. Tin Soldier 14. Somebody Help Me 15. I Can't Control Myself 16. Turquoise 17. For Your Love 18. It's Five O'Clock 19. Mrs. Brown You've Got a Lovely Daughter 20. Rain On the Roof 21. Mama 22. Can I Get There By Candlelight 23. You Were On My Mind 24. Mellow Yellow 25. Wishin' and Hopin' 26. Albatross 27. Seasons In the Sun 28. My Mind's Eye 29. Do You Want To Know a Secret? 30. Pretty Flamingo 31. Come and Stay With Me 32. Reflections of My Life 33. Question 34. The Legend of Xanadu 35. Bend It 36. Fire Brigade 37. Callow La Vita 38. Goodbye My Love 39. I'm Alive 40. Keep On Running 41. The Hippy Hippy Shake 42. It's Not Unusual 43. Love Is All Around 44. Don't Let Me Be Misunderstood 45. The Days of Pearly Spencer 46. The Pied Piper 47. With a Girl Like You 48. Zabadak! 49. I Only Want To Be With You 50. Here It Comes Again 51. Don't Let the Sun Catch You Crying 52. Have I the Right 53. Darling Be Home Soon 54. Only One Woman 55. -

Het Verhaal Van De 340 Songs Inhoud

Philippe Margotin en Jean-Michel Guesdon Rollingthe Stones compleet HET VERHAAL VAN DE 340 SONGS INHOUD 6 _ Voorwoord 8 _ De geboorte van een band 13 _ Ian Stewart, de zesde Stone 14 _ Come On / I Want To Be Loved 18 _ Andrew Loog Oldham, uitvinder van The Rolling Stones 20 _ I Wanna Be Your Man / Stoned EP DATUM UITGEBRACHT ALBUM Verenigd Koninkrijk : Down The Road Apiece ALBUM DATUM UITGEBRACHT 10 januari 1964 EP Everybody Needs Somebody To Love Under The Boardwalk DATUM UITGEBRACHT Verenigd Koninkrijk : (er zijn ook andere data, zoals DATUM UITGEBRACHT Verenigd Koninkrijk : 17 april 1964 16, 17 of 18 januari genoemd Verenigd Koninkrijk : Down Home Girl I Can’t Be Satisfi ed 15 januari 1965 Label Decca als datum van uitbrengen) 14 augustus 1964 You Can’t Catch Me Pain In My Heart Label Decca REF : LK 4605 Label Decca Label Decca Time Is On My Side Off The Hook REF : LK 4661 12 weken op nummer 1 REF : DFE 8560 REF : DFE 8590 10 weken op nummer 1 What A Shame Susie Q Grown Up Wrong TH TH TH ROING (Get Your Kicks On) Route 66 FIVE I Just Want To Make Love To You Honest I Do ROING ROING I Need You Baby (Mona) Now I’ve Got A Witness (Like Uncle Phil And Uncle Gene) Little By Little H ROLLIN TONS NOW VRNIGD TATEN EBRUARI 965) I’m A King Bee Everybody Needs Somebody To Love / Down Home Girl / You Can’t Catch Me / Heart Of Stone / What A Shame / I Need You Baby (Mona) / Down The Road Carol Apiece / Off The Hook / Pain In My Heart / Oh Baby (We Got A Good Thing SONS Tell Me (You’re Coming Back) If You Need Me Goin’) / Little Red Rooster / Surprise, Surprise. -

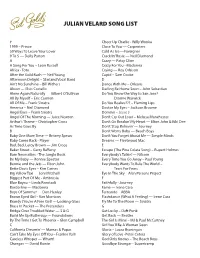

Julian Velard Song List

JULIAN VELARD SONG LIST # Cheer Up Charlie - Willy Wonka 1999 – Prince Close To You — Carpenters 50 Ways To Leave Your Lover Cold As Ice —Foreigner 9 To 5 — Dolly Parton Cracklin’ Rosie — Neil Diamond A Crazy — Patsy Cline A Song For You – Leon Russell Crazy For You - Madonna Africa - Toto Crying — Roy Orbison After the Gold Rush — Neil Young Cupid – Sam Cooke Afternoon Delight – Starland Vocal Band D Ain’t No Sunshine – Bill Withers Dance With Me – Orleans Alison — Elvis Costello Darling Be Home Soon – John Sebastian Alone Again Naturally — Gilbert O’Sullivan Do You Know the Way to San Jose? — All By Myself – Eric Carmen Dionne Warwick All Of Me – Frank Sinatra Do You Realize??? – Flaming Lips America – Neil Diamond Doctor My Eyes – Jackson Browne Angel Eyes – Frank Sinatra Domino – Jesse J Angel Of The Morning — Juice Newton Don’t Cry Out Loud – Melissa Manchester Arthur’s Theme – Christopher Cross Don’t Go Breakin’ My Heart — Elton John & Kiki Dee As Time Goes By Don’t Stop Believin’ — Journey B Don’t Worry Baby — Beach Boys Baby One More Time — Britney Spears Don’t You Forget About Me — Simple Minds Baby Come Back - Player Dreams — Fleetwood Mac Bad, Bad, Leroy Brown — Jim Croce E Baker Street – Gerry Raerty Escape (The Pina Colata Song) – Rupert Holmes Bare Necessities - The Jungle Book Everybody’s Talkin’ — Nilsson Be My Baby — Ronnie Spector Every Time You Go Away – Paul Young Bennie and the Jets — Elton John Everybody Wants To Rule The World – Bette Davis Eyes – Kim Carnes Tears For Fears Big Yellow Taxi — Joni Mitchell Eye In -

The Rita Williams Popular Song Collection a Handlist

The Rita Williams Popular Song Collection A Handlist A wide-ranging collection of c. 4000 individual popular songs, dating from the 1920s to the 1970s and including songs from films and musicals. Originally the personal collection of the singer Rita Williams, with later additions, it includes songs in various European languages and some in Afrikaans. Rita Williams sang with the Billy Cotton Club, among other groups, and made numerous recordings in the 1940s and 1950s. The songs are arranged alphabetically by title. The Rita Williams Popular Song Collection is a closed access collection. Please ask at the enquiry desk if you would like to use it. Please note that all items are reference only and in most cases it is necessary to obtain permission from the relevant copyright holder before they can be photocopied. Box Title Artist/ Singer/ Popularized by... Lyricist Composer/ Artist Language Publisher Date No. of copies Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Dans met my Various Afrikaans Carstens- De Waal 1954-57 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Careless Love Hart Van Steen Afrikaans Dee Jay 1963 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Ruiter In Die Nag Anton De Waal Afrikaans Impala 1963 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Van Geluk Tot Verdriet Gideon Alberts/ Anton De Waal Afrikaans Impala 1970 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Wye, Wye Vlaktes Martin Vorster/ Anton De Waal Afrikaans Impala 1970 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs My Skemer Rapsodie Duffy -

Glyn Johns Sound Man a Life Recording Hits With

ISBN: 9780399163876 Author: Glyn Johns Sound Man A Life Recording Hits with The Rolling Stones, The Who, Led Zeppelin, The Eagles, Eric Clapton, The Faces . Excerpt PREFACE Someone asked me the other day: What exactly does a record producer do? My answer was: “You just have to have an opinion and the ego to express it more convincingly than anyone else.” Every time I start another project I wonder if I am going to get found out. So much of what any of us achieve in life has a massive element of good fortune attached. In my case, you can start with being born in 1942, which tipped me out into the workplace just as things were getting interesting in the music business, along with a whole host of artists who were to change the face of popular music. They were to drag me with them on the crest of a wave through an extraordinary period of change, not only in the music they were writing and performing but in the structure of the industry itself. Every now and then, when the opportunity presented itself, I would try to “express my opinion more convincingly than anyone else,” and there were a few who took notice. I started working as a recording engineer in 1959, just before the demise of the 78. It was the beginning of the vinyl age. Mono was the thing and stereo was only for hi-fi freaks. Bill Haley and His Comets had started the American rock and roll invasion in Britain in the mid-fifties, and it had been rammed home by Elvis, Fats Domino, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Chuck Berry, to name but a few.