Sinn Féin in the EU

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

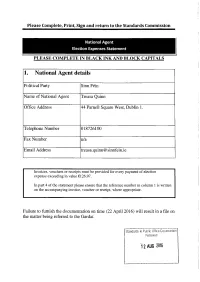

Sinn-Fein-NA-EES.Pdf

Candidate Name Constituency Amount Assigned Total Expenditure on the candidate by the national agent € € 1. Micheal MacDonncha Dublin Bay North 5000 2.Denise Mitchell Dublin Bay North 5000 3.Chris Andrews Dublin Bay South 5000 450.33 4.Mary Lou McDonald Dublin Central 4000 5.Louise O’Reilly Dublin Fingal 8000 2449.33 6. Eoin O’Broin Dublin Mid West 3000 7. Dessie Ellis Dublin North West 3000 8.Cathleen Carney Boud Dublin North West 5000 9.Sorcha Nic Cormaic Dublin Rathdown 5000 10.Aengus Ó Snodaigh Dublin South 3000 Central 11.Màire Devine Dublin South 3000 Central 12. Sean Crowe Dublin South West 3000 13.Sarah Holland Dublin South West 5000 14.Paul Donnelly Dublin West 3000 69.50 15.Shane O’Brien Dun Laoghaire 5000 73.30 16.Caoimhghìn Ó Caoláin Cavan Monaghan 3000 129.45 17.Kathryn Reilly Cavan Monaghan 3000 192.20 18.Pearse Doherty Donegal 3000 19.Pádraig MacLochlainn Donegal 3000 20.Garry Doherty Donegal 3000 21.Annemarie Roche Galway East 5000 22.Trevor O’Clochartaigh Galway West 5000 73.30 23.Réada Cronin Kildare North 5000 24.Patricia Ryan Kildare South 5000 13.75 25.Brian Stanley Laois 3000 255.55 26.Paul Hogan Longford 5000 Westmeath 27.Gerry Adams Louth 3000 28.Imelda Munster Louth 10000 29.Rose Conway Walsh Mayo 10000 560.57 30.Darren O’Rourke Meath East 6000 31.Peadar Tòibìn Meath West 3000 247.57 32.Carol Nolan Offaly 4000 33.Claire Kerrane Roscommon Galway 5000 34.Martin Kenny Sligo Leitrim 3000 193.36 35.Chris MacManus Sligo Leitrim 5000 36.Kathleen Funchion Carlow Kilkenny 5000 37.Noeleen Moran Clare 5000 794.51 38.Pat Buckley Cork East 6000 202.75 39.Jonathan O’Brien Cork North Central 3000 109.95 40.Thomas Gould Cork North Central 5000 109.95 41.Nigel Dennehy Cork North West 5000 42.Donnchadh Cork South Central 3000 O’Laoghaire 43.Rachel McCarthy Cork south West 5000 101.64 44.Martin Ferris Kerry County 3000 188.62 45.Maurice Quinlivan Limerick City 3000 46.Seamus Browne Limerick City 5000 187.11 47.Seamus Morris Tipperary 6000 1428.49 48.David Cullinane Waterford 3000 565.94 49.Johnny Mythen Wexford 10000 50.John Brady Wicklow 5000 . -

John F. Morrison Phd Thesis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository 'THE AFFIRMATION OF BEHAN?' AN UNDERSTANDING OF THE POLITICISATION PROCESS OF THE PROVISIONAL IRISH REPUBLICAN MOVEMENT THROUGH AN ORGANISATIONAL ANALYSIS OF SPLITS FROM 1969 TO 1997 John F. Morrison A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2010 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/3158 This item is protected by original copyright ‘The Affirmation of Behan?’ An Understanding of the Politicisation Process of the Provisional Irish Republican Movement Through an Organisational Analysis of Splits from 1969 to 1997. John F. Morrison School of International Relations Ph.D. 2010 SUBMISSION OF PHD AND MPHIL THESES REQUIRED DECLARATIONS 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, John F. Morrison, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 82,000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September 2005 and as a candidate for the degree of Ph.D. in May, 2007; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2005 and 2010. Date 25-Aug-10 Signature of candidate 2. Supervisor’s declaration: I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of Ph.D. -

Brochure: Ireland's Meps 2019-2024 (EN) (Pdf 2341KB)

Clare Daly Deirdre Clune Luke Ming Flanagan Frances Fitzgerald Chris MacManus Seán Kelly Mick Wallace Colm Markey NON-ALIGNED Maria Walsh 27MEPs 40MEPs 18MEPs7 62MEPs 70MEPs5 76MEPs 14MEPs8 67MEPs 97MEPs Ciarán Cuffe Barry Andrews Grace O’Sullivan Billy Kelleher HHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH Printed in November 2020 in November Printed MIDLANDS-NORTH-WEST DUBLIN SOUTH Luke Ming Flanagan Chris MacManus Colm Markey Group of the European United Left - Group of the European United Left - Group of the European People’s Nordic Green Left Nordic Green Left Party (Christian Democrats) National party: Sinn Féin National party: Independent Nat ional party: Fine Gael COMMITTEES: COMMITTEES: COMMITTEES: • Budgetary Control • Agriculture and Rural Development • Agriculture and Rural Development • Agriculture and Rural Development • Economic and Monetary Affairs (substitute member) • Transport and Tourism Midlands - North - West West Midlands - North - • International Trade (substitute member) • Fisheries (substitute member) Barry Andrews Ciarán Cuffe Clare Daly Renew Europe Group Group of the Greens / Group of the European United Left - National party: Fianna Fáil European Free Alliance Nordic Green Left National party: Green Party National party: Independents Dublin COMMITTEES: COMMITTEES: COMMITTEES: for change • International Trade • Industry, Research and Energy • Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs • Development (substitute member) • Transport and Tourism • International Trade (substitute member) • Foreign Interference in all Democratic • -

Mary Macswiney Was First Publicly Associated

MacSwiney, Mary by Brian Murphy MacSwiney, Mary (1872–1942), republican, was born 27 March 1872 at Bermondsey, London, eldest of seven surviving children of an English mother and an Irish émigré father, and grew up in London until she was seven. Her father, John MacSwiney, was born c.1835 on a farm at Kilmurray, near Crookstown, Co. Cork, while her mother Mary Wilkinson was English and otherwise remains obscure; they married in a catholic church in Southwark in 1871. After the family moved to Cork city (1879), her father started a snuff and tobacco business, and in the same year Mary's brother Terence MacSwiney (qv) was born. After his business failed, her father emigrated alone to Australia in 1885, and died at Melbourne in 1895. Nonetheless, before he emigrated he inculcated in all his children his own fervent separatism, which proved to be a formidable legacy. Mary was beset by ill health in childhood, her misfortune culminating with the amputation of an infected foot. As a result, it was at the late age of 20 that she finished her education at St Angela's Ursuline convent school in 1892. By 1900 she was teaching in English convent schools at Hillside, Farnborough, and at Ventnor, Isle of Wight. Her mother's death in 1904 led to her return to Cork to head the household, and she secured a teaching post back at St Angela's. In 1912 her education was completed with a BA from UCC. The MacSwiney household of this era was an intensely separatist household. Avidly reading the newspapers of Arthur Griffith (qv), they nevertheless rejected Griffith's dual monarchy policy. -

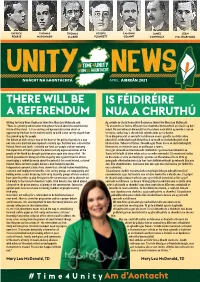

April Unity News

PATRICK THOMAS THOMAS JOSEPH ÉAMONN JAMES SEÁN PEARSE McDONAGH CLARKE PLUNKETT CEANNT CONNOLLY Mac DIARMADA #Time4Unity UNITY# AM LE hAONTACHT NEWS NUACHT NA hAONTACHTA APRIL AIBREÁN 2021 THERE WILL BE IS FÉIDIRÉIRE AWriting forREFERENDUM Unity News Úachtaran Shinn Féin Mary Lou McDonald said: AgNUA scríobh do Unity News A dúirt ÚachtaranCHRUTHÚ Shinn Féin Mary Lou McDonald: “There is a growing conversation throughout Ireland about the constitutional “Tá an comhrá ar fud na hÉireann faoi thodhchaí bunreachtúil an oileáin ag dul i future of the island. It is an exciting and dynamic discussion about an méad. Plé corraitheach dinimiciúil atá faoi dheis nach bhfuil ag mórán i saol an opportunity few have in the modern world; to build a new society shaped from lae inniu; sochaí nua a chruthú ón talamh aníos ag na daoine. the ground up by the people. Tá an díospóireacht ar aontacht na hÉireann anois i gcroílár an chláir oibre The debate on Irish unity is now at the heart of the political agenda in a way pholaitiúil ar bhealach nach bhfacthas ó cuireadh an chríochdheighilt céad not seen since partition was imposed a century ago. Partition was a disaster for bliain ó shin. Tubaiste d’Éirinn, Thuaidh agus Theas ba ea an chríochdheighilt. Ireland, North and South. It divided our land, our people and our economy. Rinnean tír, an mhuintir agus an geilleagar a roinnt. The imposition of Brexit against the democratically expressed wishes of the Toisc gur cuireadh an Breatimeacht i bhfeidhm i gcoinne thoil mhuintir an people of the North has brought partition once again into sharp relief. -

Dáil Éireann

Vol. 995 Wednesday, No. 1 15 July 2020 DÍOSPÓIREACHTAÍ PARLAIMINTE PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES DÁIL ÉIREANN Insert Date Here 15/07/2020A00100Financial Provisions (Covid-19) Bill 2020: Second Stage (Resumed) � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 2 15/07/2020F00100Gnó na Dála - Business of Dáil � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 12 15/07/2020G00100Ceisteanna - Questions � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 12 15/07/2020G00200Ceisteanna ar Sonraíodh Uain Dóibh - Priority Questions � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 12 15/07/2020G00250Renewable Energy Generation � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 12 15/07/2020G00950Cybersecurity Policy � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 14 15/07/2020H00600Fuel Poverty � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 16 15/07/2020J00400Bord na Móna � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 18 15/07/2020K00150North-South Interconnector � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 20 15/07/2020K01000Ceisteanna Eile -

Ireland and the Basque Country: Nationalisms in Contact, 1895-1939

Ireland and the Basque Country: Nationalisms in Contact, 1895-1939 Kyle McCreanor A Thesis in the Department of History Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts (History) at Concordia University Montréal, Québec, Canada March 2019 © Kyle McCreanor, 2019 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Kyle McCreanor Entitled: Ireland and the Basque Country: Nationalisms in Contact, 1895-1939 and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (History) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final Examining Committee: _________________________________ Chair Dr. Andrew Ivaska _________________________________ Examiner Dr. Ted McCormick _________________________________ Examiner Dr. Cameron Watson _________________________________ Supervisor Dr. Gavin Foster Approved by _________________________________________________________ Chair of Department or Graduate Program Director _______________ 2019 _________________________________________ Dean of Faculty iii Abstract Ireland and the Basque Country: Nationalisms in Contact, 1895-1939 Kyle McCreanor This thesis examines the relationships between Irish and Basque nationalists and nationalisms from 1895 to 1939—a period of rapid, drastic change in both contexts. In the Basque Country, 1895 marked the birth of the Partido Nacionalista Vasco (Basque Nationalist Party), concurrent with the development of the cultural nationalist movement known as the ‘Gaelic revival’ in pre-revolutionary Ireland. In 1939, the Spanish Civil War ended with the destruction of the Spanish Second Republic, plunging Basque nationalism into decades of intense persecution. Conversely, at this same time, Irish nationalist aspirations were realized to an unprecedented degree during the ‘republicanization’ of the Irish Free State under Irish leader Éamon de Valera. -

The Hungerstrikes

anIssue 5 Jul-Sept 2019 £2.50/€3.00 spréachIndependent non-profit Socialist Republican magazine THE HUNGERSTRIKES PIVOTAL MOMENTS IN OUR HISTORY Where’s the Pleasure? Examining Sexual Morality Under Capitalism An EU Immigrant The Craigavon 2 More Than A I’m Irish and Pro- A Miscarriage of Beautiful Game Leave Justice Soccer and Politics DIGITAL BACK ISSUES of anspréach Magazine are available for download via our website. Just visit www.anspreach.org ____ Dear reader, An Spréach is an independent Socialist Republican magazine formed by a collective of political activists across Ireland. It aims to bring you, the read- er, a broad swathe of opinion from within the Irish Socialist Republican political sphere, including, but not exclusive to, the fight for national liberation and socialism in Ireland and internationally. The views expressed herein, do not necesserily represent the publication and are purely those of the author. We welcome contributions from all political activists, including opinion pieces, letters, historical analyses and other relevant material. The editor reserves the right to exclude or omit any articles that may be deemed defamatory or abusive. Full and real names must be provided, even in instances where a pseudonym is used, including contact details. Please bear in mind that you may be asked to shorten material if necessary, and where we may be required to edit a piece to fit within these pages, all efforts will be made to retain its balance and opinion, without bias. An Spréach is a not-for-profit magazine which only aims to fund its running costs, including print and associated platforms. -

1. Debbie Abrahams, Labour Party, United Kingdom 2

1. Debbie Abrahams, Labour Party, United Kingdom 2. Malik Ben Achour, PS, Belgium 3. Tina Acketoft, Liberal Party, Sweden 4. Senator Fatima Ahallouch, PS, Belgium 5. Lord Nazir Ahmed, Non-affiliated, United Kingdom 6. Senator Alberto Airola, M5S, Italy 7. Hussein al-Taee, Social Democratic Party, Finland 8. Éric Alauzet, La République en Marche, France 9. Patricia Blanquer Alcaraz, Socialist Party, Spain 10. Lord John Alderdice, Liberal Democrats, United Kingdom 11. Felipe Jesús Sicilia Alférez, Socialist Party, Spain 12. Senator Alessandro Alfieri, PD, Italy 13. François Alfonsi, Greens/EFA, European Parliament (France) 14. Amira Mohamed Ali, Chairperson of the Parliamentary Group, Die Linke, Germany 15. Rushanara Ali, Labour Party, United Kingdom 16. Tahir Ali, Labour Party, United Kingdom 17. Mahir Alkaya, Spokesperson for Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation, Socialist Party, the Netherlands 18. Senator Josefina Bueno Alonso, Socialist Party, Spain 19. Lord David Alton of Liverpool, Crossbench, United Kingdom 20. Patxi López Álvarez, Socialist Party, Spain 21. Nacho Sánchez Amor, S&D, European Parliament (Spain) 22. Luise Amtsberg, Green Party, Germany 23. Senator Bert Anciaux, sp.a, Belgium 24. Rt Hon Michael Ancram, the Marquess of Lothian, Former Chairman of the Conservative Party, Conservative Party, United Kingdom 25. Karin Andersen, Socialist Left Party, Norway 26. Kirsten Normann Andersen, Socialist People’s Party (SF), Denmark 27. Theresa Berg Andersen, Socialist People’s Party (SF), Denmark 28. Rasmus Andresen, Greens/EFA, European Parliament (Germany) 29. Lord David Anderson of Ipswich QC, Crossbench, United Kingdom 30. Barry Andrews, Renew Europe, European Parliament (Ireland) 31. Chris Andrews, Sinn Féin, Ireland 32. Eric Andrieu, S&D, European Parliament (France) 33. -

Hon. Mr President of the European Parliament, Dear David Sassoli

Hon. Mr President of the European Parliament, Dear David Sassoli, Since March, when the outbreak of COVID-19 intensified in Europe, the functioning of the European Parliament (EP) has changed dramatically, due to the sanitary measures applied. We understand the inevitability of the contingency plan, taking into account the need to prevent infection and the spread of the virus and to protect the health and lives of people. Six months later, the functioning of the EP is gradually returning to normal. However, there are services whose unavailability seriously impairs parliamentary work, namely the interpretation service. The European Union (EU) has 24 official languages and all deserve the same respect and treatment. We recognize that the number of languages available in committee meeting rooms has been increasing, but even so, more than half of the languages still have no interpretation. Multilingualism is a right enshrined in the Treaties that allows Members to express themselves in their own language. Now, that is not happening and we are concerned that the situation will continue, even taking into account the expected workflow in the commissions after these atypical six months. In this sense, we appeal, once again, to you, the President of the EP for the application of the letter and the spirit of the principle of multilingualism, finding solutions that respect this principle and that allow the use of any of the 24 official languages of the EU. The expression of each deputy in her/his own language is a priority so that there can be conditions to fully exercise the mandate for which she/he was elected and a condition of respect for the citizens who elected her/him. -

Lettre Conjointe De 1.080 Parlementaires De 25 Pays Européens Aux Gouvernements Et Dirigeants Européens Contre L'annexion De La Cisjordanie Par Israël

Lettre conjointe de 1.080 parlementaires de 25 pays européens aux gouvernements et dirigeants européens contre l'annexion de la Cisjordanie par Israël 23 juin 2020 Nous, parlementaires de toute l'Europe engagés en faveur d'un ordre mondial fonde ́ sur le droit international, partageons de vives inquietudeś concernant le plan du president́ Trump pour le conflit israeló -palestinien et la perspective d'une annexion israélienne du territoire de la Cisjordanie. Nous sommes profondement́ preoccuṕ eś par le preć edent́ que cela creerait́ pour les relations internationales en geń eral.́ Depuis des decennies,́ l'Europe promeut une solution juste au conflit israeló -palestinien sous la forme d'une solution a ̀ deux Etats,́ conformement́ au droit international et aux resolutionś pertinentes du Conseil de securit́ e ́ des Nations unies. Malheureusement, le plan du president́ Trump s'ecarté des parametres̀ et des principes convenus au niveau international. Il favorise un controlê israelień permanent sur un territoire palestinien fragmente,́ laissant les Palestiniens sans souverainete ́ et donnant feu vert a ̀ Israel̈ pour annexer unilateralement́ des parties importantes de la Cisjordanie. Suivant la voie du plan Trump, la coalition israelienné recemment́ composeé stipule que le gouvernement peut aller de l'avant avec l'annexion des̀ le 1er juillet 2020. Cette decisioń sera fatale aux perspectives de paix israeló -palestinienne et remettra en question les normes les plus fondamentales qui guident les relations internationales, y compris la Charte des Nations unies. Nous sommes profondement́ preoccuṕ eś par l'impact de l'annexion sur la vie des Israelienś et des Palestiniens ainsi que par son potentiel destabilisateuŕ dans la regioń aux portes de notre continent. -

Revisionism: the Provisional Republican Movement

Journal of Politics and Law March, 2008 Revisionism: The Provisional Republican Movement Robert Perry Phd (Queens University Belfast) MA, MSSc 11 Caractacus Cottage View, Watford, UK Tel: +44 01923350994 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This article explores the developments within the Provisional Republican Movement (IRA and Sinn Fein), its politicization in the 1980s, and the Sinn Fein strategy of recent years. It discusses the Provisionals’ ending of the use of political violence and the movement’s drift or determined policy towards entering the political mainstream, the acceptance of democratic norms. The sustained focus of my article is consideration of the revision of core Provisional principles. It analyses the reasons for this revisionism and it considers the reaction to and consequences of this revisionism. Keywords: Physical Force Tradition, Armed Stuggle, Republican Movement, Sinn Fein, Abstentionism, Constitutional Nationalism, Consent Principle 1. Introduction The origins of Irish republicanism reside in the United Irishman Rising of 1798 which aimed to create a democratic society which would unite Irishmen of all creeds. The physical force tradition seeks legitimacy by trying to trace its origin to the 1798 Rebellion and the insurrections which followed in 1803, 1848, 1867 and 1916. Sinn Féin (We Ourselves) is strongly republican and has links to the IRA. The original Sinn Féin was formed by Arthur Griffith in 1905 and was an umbrella name for nationalists who sought complete separation from Britain, as opposed to Home Rule. The current Sinn Féin party evolved from a split in the republican movement in Ireland in the early 1970s. Gerry Adams has been party leader since 1983, and led Sinn Féin in mutli-party peace talks which resulted in the signing of the 1998 Belfast Agreement.