2-Chapter 1 Intro and Methods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spotted Seals, Phoca Largha, in Alaska

Spotted Seals, Phoca largha, in Alaska Item Type article Authors Rugh, David J.; Shelden, Kim E. W.; Withrow, David E. Download date 09/10/2021 03:34:27 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/26448 Spotted Seals, Phoca largha, in Alaska DAVID J. RUGH, KIM E. W. SHELDEN, and DAVID E. WITHROW Introduction mine the abundance, distribution, and lar), a 2-month difference in mating sea stock identification of marine mammals sons (effecting reproductive isolation), Under the reauthorization of the Ma that might have been impacted by com the whitish lanugo on newborn P largha rine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA) mercial fisheries in U.S. waters (Bra that is shed in utero in P vitulina, dif in 1988, and after a 5-year interim ex ham and DeMaster1). For spotted seals, ferences in the adult pelage of P largha emption period ending September 1995, Phoca largha, there were insufficient and P vitulina, and some differences in the incidental take of marine mammals data to determine incidental take lev cranial characteristics (Burns et aI., in commercial fisheries was authorized els. Accordingly, as a part of the MMAP, 1984). However, hybridization may if the affected populations were not ad the NMFS National Marine Mammal occur, based on evidence from morpho versely impacted. The Marine Mammal Laboratory (NMML) conducted a study logical intermediates and overlaps in Assessment Program (MMAP) of the of spotted seals in Alaska. The objec range (Bums et aI., 1984). As such, dif National Marine Fisheries Service tives of this study were to: I) provide a ferentiation of these two species in the (NMFS), NOAA, provided funding to review of literature pertaining to man field is very difficult. -

Northwest Arctic Subarea Contingency Plan

NORTHWEST ARCTIC SUBAREA CONTINGENCY PLAN SENSITIVE AREAS SECTION SENSITIVE AREAS: INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 3 SENSITIVE AREAS: PART ONE – INFORMATION SOURCES ............................................................................ 7 SENSITIVE AREAS: PART TWO – AREAS OF ENVIRONMENTAL CONCERN .................................................. 11 A. BACKGROUND/CRITERIA ................................................................................................................ 11 B. AREAS OF MAJOR CONCERN .......................................................................................................... 11 C. AREAS OF MODERATE CONCERN ................................................................................................... 13 D. AREAS OF LESSER CONCERN .......................................................................................................... 13 E. AREAS OF LOCAL CONCERN ........................................................................................................... 13 SENSITIVE AREAS: PART THREE – RESOURCE SENSITIVITY ......................................................................... 24 SENSITIVE AREAS: PART FOUR – BIOLOGICAL AND HUMAN USE RESOURCES ........................................... 34 A. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................. 34 B. HABITAT TYPES .............................................................................................................................. -

Download a Full Copy of Volume 16, Issue 1 of Alaska Park Science

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Alaska Park Science Alaska Region Science in Alaska's Arctic Parks Volume 16, Issue 1 Beaufort Sea Chukchi Sea Alaska Park Science Noatak National Preserve Volume 16, Issue 1 Cape Krusenstern Gates of the Arctic National April 2017 National Monument Park and Preserve Editor in Chief: Leigh Welling Managing Editor: Nina Chambers Kobuk Valley Arctic Circle Bering Land Bridge National Park Editor: Stacia Backensto National Preserve Guest Editors: Jim Lawler, Andrew Tremayne Design: Nina Chambers Yukon-Charley Rivers S K A National Preserve Contact Alaska Park Science at: L A [email protected] A Gulf of Alaska Bering Sea Alaska Park Science is the semi-annual science journal of the National Park Service Alaska Region. Each issue highlights research and scholarship on a theme important to the stewardship of Alaska’s parks. Publication in Alaska Park Science does not signify that the contents reflect the views or policies of the National Park Service, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute National Park Service endorsement or recommendation. Alaska Park Science can be found online at: www.nps.gov/subjects/alaskaparkscience/index.htm Table of Contents Alaska’s Northern Parks: The Wonder of the Applying Wilderness Character Monitoring Collaborative Conservation of the Rare Arctic ...............................................................1 in the Arctic .................................................37 Alaskan Yellow-billed Loon ........................79 -

Accidental Oil Spills and Gas Releases;

APPENDIX A Accidental Oil Spills and Gas Releases; Information, Models, and Estimates; and Supporting Figures, Tables, and Maps Posted at: https://www.boem.gov/Liberty/ This page intentionally left blank. Appendix A Liberty Development and Production Plan Final EIS Table of Contents Contents A-1 Accidental Large Oil Spills ...................................................................................... 1 A-1.1 Large Spill Size, Source, and Oil-Type Assumptions ............................................................ 1 A-1.1.1 OCS Large Oil Spill Sizes .......................................................................................... 1 A-1.1.2 Onshore Large Oil Pipeline Spill Size ........................................................................ 1 A-1.1.3 Source and Type of Large Oil Spills .......................................................................... 2 A-1.1.4 Historical Loss of Well-Control Incidents on the OCS and North Sea ....................... 2 A-1.2 Behavior and Fate of Crude Oils ............................................................................................ 3 A-1.2.1 Generalized Processes Affecting the Fate and Behavior of Oil................................. 3 A-1.2.2 Assumptions about Oil Spill Weathering .................................................................... 4 A-1.2.3 Modeling Simulations of Oil Weathering .................................................................... 4 A-1.3 Estimates of Where a Large Offshore Oil Spill May Go ........................................................ -

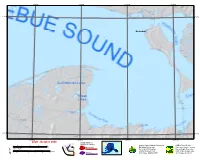

Kotzebue Nulvororok Lake Kotzebue Nulvororok Channel

165°0'0"W 164°0'0"W 163°0'0"W 162°0'0"W Milokrawlok CreekSitukuyok River Kilangnak Bluff Aukulak Lagoon Tukrok River Shiliak Creek Kinuk Island 67°0'0"N Sheshalik Spit Little Noatak Slough 67°0'0"N Noatak River Delta Sheshalik Noatak River Pipe Spit Kotzebue Nulvororok Lake Kotzebue Nulvororok Channel Hotham Inlet Melvin Channel Riley Channel Cape Blossom Lewis Rich Channel Olikatuk Channel EEspsepnebnebregrg River Northwest Corner LightKitluk River Cape Espenberg Kalik River Baldwin Peninsula Kotzebue Sound Kividlo Singeak Singeakpuk River West Fork Espenberg River Devil Mountain Lakes Kungealarook Creek Cowpack Inlet Devil Mountain Lakes Cowpack River White Fish Lake Killeak Lakes Kungealoruk Creek Branch Cowpack River Killeak Devil Mountain Lakes Choris Peninsula Point Garnet Kougachuk Creek Chamisso Anchorage Puffin Island Chamisso National Wildlife RefugeChamisso Island Lane River Nugnugaluktuk River Church Rock Pish River T Eldorado Creek South Fork Serpentine River North Fork Serpentine River Goodhope Bay I Spafarief Bay Rock Creek Cape Deceit Toawlevic Point Rex Point Clifford Point Clifford Creek Motherwood Point Rex Creek Goodnews Bay DeeringDeering SImnmitha cChrueke kRiver Cripple River Grayling Creek Sullivan Creek Sullivan Bluffs Francis Creek Ninemile Point Alder Creek Reindeer Creek Sullivan Lake Hunter Creek Willow Bay Lone Butte Creek CamWpil loCwre Cekreek A Kugruk Lagoon Kirk Creek Kiwalik Eagle Creek Minnehaha Creek 66°0'0"N Kugruk River Lava Creek Pot Creek Iowa Creek Virginia Creek Inmachuk River 66°0'0"N Humbolt -

GIS Spatial Analysis of Arctic Settlement Patterns: a Case Study in Northwest Alaska

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Spring 9-5-2017 GIS Spatial Analysis of Arctic Settlement Patterns: A Case Study in Northwest Alaska Justin Andrew Junge Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Anthropology Commons, and the Geographic Information Sciences Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Junge, Justin Andrew, "GIS Spatial Analysis of Arctic Settlement Patterns: A Case Study in Northwest Alaska" (2017). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 3878. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.5766 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. GIS Spatial Analysis of Arctic Settlement Patterns: A Case Study in Northwest Alaska by Justin Andrew Junge A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Anthropology Thesis Committee: Shelby L. Anderson, Chair Kenneth M. Ames David Banis Portland State University 2017 © 2017 Justin Andrew Junge Abstract Archaeologists have been interested in relationship between environmental variability and cultural change for the last six decades. By understanding how, when, and why humans adapt to environmental change, archaeologists and anthropologists can better understand the development and complexity of human cultures. In northwest Alaska, archaeologists hypothesize that environmental variability was a major factor in both growing coastal population density, with large aggregated villages and large houses, between 1000 and 500 years ago (ya), and subsequent decreasing population density between 500 ya and the contact era. -

2015 Shell Chukchi Sea Revised Exploration Plan Environmental

Alaska Outer Continental Shelf OCS EIS/EA BOEM 2015-020 Shell Gulf of Mexico, Inc. Revised Outer Continental Shelf Lease Exploration Plan Chukchi Sea, Alaska Burger Prospect: Posey Area Blocks 6714, 6762, 6764, 6812, 6912, 6915 Revision 2 (March 2015) ENVIRONMENTAL assessmeNT U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management May 2015 Alaska OCS Region This Page Intentionally Left Blank Alaska Outer Continental Shelf OCS EIS/EA BOEM 2015-020 Shell Gulf of Mexico, Inc. Revised Outer Continental Shelf Lease Exploration Plan Chukchi Sea, Alaska Burger Prospect: Posey Area Blocks 6714, 6762, 6764, 6812, 6912, 6915 Revision 2 (March 2015) ENVIRONMENTAL assessmeNT Prepared By: Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Alaska OCS Region Office of Environment Cooperating Agencies: U.S. Department of this Interior Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement Bureau of Land Management State of Alaska North Slope Borough U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management May 2015 Alaska OCS Region This Page Intentionally Left Blank Environmental Assessment 2015 Shell Chukchi Sea EP EA Acronyms and Abbreviations AAAQS .........................Alaska Ambient Air Quality Standards AAQS ............................Ambient Air Quality Standards ACP ...............................Arctic Coastal Plain ADEC ............................Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation ADF&G .........................Alaska Department of Fish and Game AEWC ...........................Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission ANS ...............................Alaska -

Shorezone Aerial Video Imaging Survey

CORI Project: 12-15 October 2012 FLIGHT REPORT ShoreZone Aerial Video Imaging (AVI) Survey Northwest Alaska July 18-22, 2012 Team Kotzebue (KZ) ·,. --.. ... Chukchi Sea Wales 25 10 1-- Team Kotzebue - 3,095 km I prepared for: ---- ~ ShoreZone \·~~ \ National Park Service - NPS Coastal & Ocean Resources Inc. COASTAL & OCEAN RESOURCES INC. 759-A Vanalman Avenue. Victoria, BC. V8Z 3B8. Canada ph: 250.658.4050, web: www.coastalandoceans.com, email: [email protected] SUMMARY The purpose of this flight report is to summarize the field activities of the ShoreZone aerial video imaging (AVI) survey conducted out of Nome and Kotzebue in Northwest Alaska during July 18-22, 2012. The survey was conducted by Coastal & Ocean Resources Inc. (CORI) under contract with the National Park Service (NPS). A coastal ecologist from Archipelago Marine Research Ltd (AMRL) provided biological observations during the flights. Table1 provides a summary of crew affiliations and responsibilities. The tables and figures on the following pages summarize the extent and location of the 3,095 km (*based on the digital Alaska Coastline 1:63,360) of AVI data and imagery collected by the team. The teams utilized a Robinson R-44 helicopter charted from Bering Air in Nome, Alaska. Imagery was collected looking at the shoreline from the left side of the aircraft with the doors removed. A total of 27 HD mini DV master tapes were collected during the survey and recorded to DVDs. This report contains a summary table for each tape, illustrating its location, length, and key geographic points. Maps for each tape are annotated with representative geographic names, trackline times (hh:mm:ss UTC; UTC time is 8 hours ahead of Alaska Daylight Time), and photo numbers. -

Fortune's Distant Shores

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Gates of the Arctic National Park & Preserve FORTUNE’S DISTANT SHORES A History of the Kotzebue Sound Gold Stampede in Alaska’s Arctic CHRIS ALLAN As the nation’s principal conservation agency, the Department of the Interior has responsibility for most of our nationally owned public lands and natural and cultural resources. This includes fostering the wisest use of our land and water resources, protecting our fish and wildlife, preserving the environmental and cultural values of our national parks and historical places, and providing for enjoyment of life through outdoor recreation. The Cultural Resource Programs of the National Park Service have responsibilities that include stewardship of historic buildings, museum collections, archeological sites, cultural landscapes, oral and written histories, and ethnographic resources. Our mission is to identify, evaluate and preserve the cultural resources of the park areas and to bring an understanding of these resources to the public. Congress has mandated that we preserve these resources because they are important components of our national and personal identity. Published by the United States Department of the Interior through the Government Printing Office with the assistance of Debra A. Mingeaud. Fortune’s Distant Shores A History of the Kotzebue Sound Gold Stampede in Alaska’s Arctic Chris Allan ISBN-978-0-578-47663-6 2019 Front Cover: Carl von Knobelsdorff, known as “The Flying Dutchman,” traveled hundreds of miles on ice skates along the Kobuk River delivering news and personal letters for one dollar each, ca. 1898. Bancroft Library, Samuel W. Fansher Collection (2015.79). -

Science in Alaska's Arctic Parks

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Alaska Park Science Alaska Region Science in Alaska's Arctic Parks Volume 16, Issue 1 Beaufort Sea Chukchi Sea Alaska Park Science Noatak National Preserve Volume 16, Issue 1 Cape Krusenstern Gates of the Arctic National April 2017 National Monument Park and Preserve Editor in Chief: Leigh Welling Managing Editor: Nina Chambers Kobuk Valley Arctic Circle Bering Land Bridge National Park Editor: Stacia Backensto National Preserve Guest Editors: Jim Lawler, Andrew Tremayne Design: Nina Chambers Yukon-Charley Rivers S K A National Preserve Contact Alaska Park Science at: L A [email protected] A Gulf of Alaska Bering Sea Alaska Park Science is the semi-annual science journal of the National Park Service Alaska Region. Each issue highlights research and scholarship on a theme important to the stewardship of Alaska’s parks. Publication in Alaska Park Science does not signify that the contents refect the views or policies of the National Park Service, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute National Park Service endorsement or recommendation. Alaska Park Science can be found online at: www.nps.gov/subjects/alaskaparkscience/index.htm Table of Contents Alaska’s Northern Parks: The Wonder of the Applying Wilderness Character Monitoring Collaborative Conservation of the Rare Arctic ...............................................................1 in the Arctic .................................................37 Alaskan Yellow-billed Loon ........................79 -

Kotzebue Flight Log 2012

CORI Project: 12-15 October 2012 FLIGHT REPORT ShoreZone Aerial Video Imaging (AVI) Survey Northwest Alaska July 18-22, 2012 Team Kotzebue (KZ) prepared for: National Park Service - NPS COASTAL & OCEAN RESOURCES INC. 759-A Vanalman Avenue. Victoria, BC. V8Z 3B8. Canada ph: 250.658.4050, web: www.coastalandoceans.com, email: [email protected] SUMMARY The purpose of this flight report is to summarize the field activities of the ShoreZone aerial video imaging (AVI) survey conducted out of Nome and Kotzebue in Northwest Alaska during July 18-22, 2012. The survey was conducted by Coastal & Ocean Resources Inc. (CORI) under contract with the National Park Service (NPS). A coastal ecologist from Archipelago Marine Research Ltd (AMRL) provided biological observations during the flights. Table1 provides a summary of crew affiliations and responsibilities. The tables and figures on the following pages summarize the extent and location of the 3,095 km (*based on the digital Alaska Coastline 1:63,360) of AVI data and imagery collected by the team. The teams utilized a Robinson R-44 helicopter charted from Bering Air in Nome, Alaska. Imagery was collected looking at the shoreline from the left side of the aircraft with the doors removed. A total of 27 HD mini DV master tapes were collected during the survey and recorded to DVDs. This report contains a summary table for each tape, illustrating its location, length, and key geographic points. Maps for each tape are annotated with representative geographic names, trackline times (hh:mm:ss UTC; UTC time is 8 hours ahead of Alaska Daylight Time), and photo numbers. -

May 1954 NAMES and DEFINITIONS of REGIONS, DISTRICTS, and SUBDISTRICTS in ALASKA

NAMES AND DEFINITIONS OF REGIONS, DISTRICTS, AND SUBDISTRICTS IN ALASKA (Used by the Bureau of Mines in Statistical and Economic Studies Covering the Mineral Industry of the Territory) BY ALFRED L. RANSOME AND WILLIAM H. KERNS * * * * * * * * * Information Circular 7679 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Douglas McKay, Secretary BUREAU OF MINES J. J. Forbes, Director Work on manuscript completed October 1953. The Bureau of Mines will welcome reprinting of this paper, provided the following footnote acknowledgment is made: "Reprinted from Bureau of Mines Information Circular 7679." May 1954 NAMES AND DEFINITIONS OF REGIONS, DISTRICTS, AND SUBDISTRICTS IN ALASKA (Used by the Bureau of Mines in statistical and economic studies concerning the mineral industry of the Territory) by Alfred L. Ransomel/ and William H. Kerns2/ CONTENTS Page Introduction.................................................... 1 Purpose of report .... .................................... 1 Problem of standardization of names and definitions........ 1 Development of Bureau of Mines system ..................... 2 Correlation of districts with recording precincts ......... 4 Acknowledgments................................................ 5 General selected bibliography of the mineral industry in Alaska 5 Index to regions, districts, and subdistricts.............. ...... 6 Section I - Alphabetical index to regions ................. 6 Section II - Alphabetical index to districts.............. 10 Section III - Alphabetical index to subdistricts.......... 12 Definitions