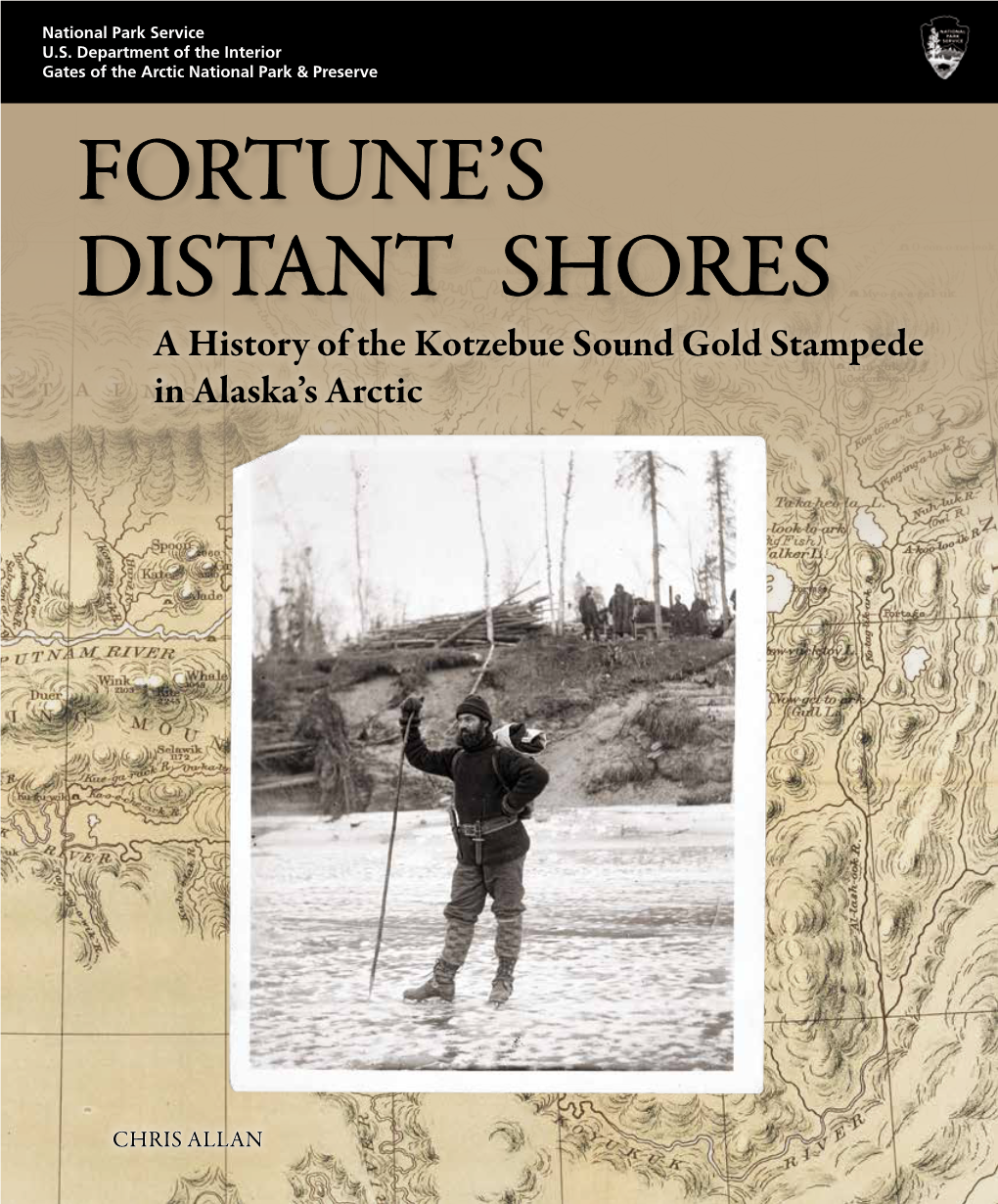

Fortune's Distant Shores

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

10.9 De Jesus Precarious Girlhood Dissertation Draft

! ! "#$%&#'()*!+'#,-((./!"#(0,$1&2'3'45!6$%(47'5)#$.!8#(9$*!(7!:$1'4'4$!;$<$,(91$42! '4!"(*2=>??@!6$%$**'(4&#A!B'4$1&! ! ! ;$*'#C$!.$!D$*)*! ! ! ! ! E!8-$*'*! F4!2-$!! G$,!H(99$4-$'1!I%-((,!(7!B'4$1&! ! ! ! ! "#$*$42$.!'4!"'&,!:),7',,1$42!(7!2-$!6$J)'#$1$42*! :(#!2-$!;$5#$$!(7! ;(%2(#!(7!"-',(*(9-A!K:',1!&4.!G(<'45!F1&5$!I2).'$*L! &2!B(4%(#.'&!M4'<$#*'2A! G(42#$&,N!O)$0$%N!B&4&.&! ! ! ! ! ! P%2(0$#!>?Q@! ! R!;$*'#C$!.$!D$*)*N!>?Q@ ! ! CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Desirée de Jesus Entitled: Precarious Girlhood: Problematizing Reconfigured Tropes of Feminine Development in Post-2009 Recessionary Cinema and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Film and Moving Image Studies complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: Chair Dr. Lorrie Blair External Examiner Dr. Carrie Rentschler External to Program Dr. Gada Mahrouse Examiner Dr. Rosanna Maule Examiner Dr. Catherine Russell Thesis Supervisor Dr. Masha Salazkina Approved by Dr. Masha Salazkina Chair of Department or Graduate Program Director December 4, 2019 Dr. Rebecca Duclos Dean Faculty of Fine Arts ! ! "#$%&"'%! ()*+,)-./0!1-)23..45!().62*7,8-9-:;!&*+.:<-;/)*4!%).=*0!.<!>*7-:-:*!?*@*2.=7*:8!-:! (.08ABCCD!&*+*00-.:,)E!'-:*7,! ! ?*0-)F*!4*!G*0/0! '.:+.)4-,!H:-@*)0-8EI!BCJD! ! !"##"$%&'()*+(,--.(/#"01#(2+3+44%"&5()*+6+($14(1(4%'&%7%31&)(3*1&'+(%&()*+(3%&+81)%3(9+:%3)%"&( -

Mutiny Simplifies Deflector Plan

` ASX: MYG Mutiny Simplifies Deflector Plan 4 August 2014 Highlights: • New management complete “Mine Operators Review” of the Deflector 2013 Definitive Feasibility Study, simplifying and optimising the Deflector Project • Mutiny Board has resolved to pursue financing and development of the Deflector project based on the new mine plan • New mine plan reduces open pit volume by 80% based on both rock properties and ore thickness, and establishes early access to the underground mine • Processing capital and throughput revised to align with optimal underground production rate of 380,000 tonnes per annum • Payable metal of 365,000 gold ounces, 325,000 silver ounces, and 15,000 copper tonnes • Pre-production capital of $67.6M • C1 cash cost of $549 per gold ounce • All in sustaining cost of $723 per gold ounce • Exploration review completed with primary focus to be placed on the 7km long, under explored, “Deflector Corridor” Note: Payable metal and costs presented in the highlights are taken from the Life of Mine Inventory model (LOM Inventory). All currency in AUS$ unless marked. Mutiny Gold Ltd (ASX:MYG) (“Mutiny” or “The Company”) is pleased to announce that the new company management, under the leadership of Managing Director Tony James, has completed an internal “Mine Operators Review” of the Deflector gold, copper and silver project, located within the Murchison Region of Western Australia. The review was undertaken on detail associated with the 2013 Definitive Feasibility Study (DFS) (ASX announcement 2 September, 2013). Tony James, -

AN INVENTORY of MARITIME ANTIQUES and RELICS of the COOS BAY AREA REFLECTIONS of a SOMETIMES FORGOTTEN PAST by Gail E. Curtis Or

AN INVENTORY OF MARITIME ANTIQUES AND RELICS OF THE COOS BAY AREA REFLECTIONS OF A SOMETIMES FORGOTTEN PAST By Gail E. Curtis Oregon Institute of Marine Biology Summer, 1975 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ,INTRODUCTION 1 - EXPLANATIONS AND ABBREVIATIONS 6 BACKGROUND INFORMATION OF THE INVENTORIED COLLECTIONS 7 MARITIME ANTIQUES AND RELICS 17 BOAT NAME PLATES 28 HALF MODELS 29 MARITIME LITERATURE 31 MARITIME MAPS, CHARTS, AND DRAWINGS 35 MARITIME PHOTOGRAPHS 39 LIFE SAVING STATION General History 75 LIFES SAVINGS CREW, STATION AND EQUIPMENT PHOTOGRAPHS.. 76 CAPE ARAGO LIGHTHOUSE PHOTOGRAPHS 78 JETTY CONSTRUCTIONS PHOTOGRAPHS BO EARLY MARSHFIELD PHOTOGRAPHS 83 SPECIAL COLLECTIONS Victor West 87 BIBLIOGRAPHY 92 DISTRIBUTION LIST 93 INTRODUCTION Coos Bay has always been tied to the sea. From the rich estuarys earliest settlement in the 1830s, its lines of supply Ind communication have been with the sea rather than the hinter- land across the Coast Range Mountains. Even as late as 1915 when the railroad came to southwestern Dregon, the sea, the bay, and the rivers of the Coos Bay region represented the main forms of coastwise trade with California and the inter-community trade from the farms and lumber camps of the interior to the urban market areas of Marshfield (Coos Bay) and later North Bend. In some respects,modern Coos Bay remains even more tied to the sea than in the past. Emerging as a major port of international trade, mainly through the export of its forest products, Coos Bays leaders recognize their communitys future fortune lies with the sea, for a form of transportation, an important food supply, and a desirable periphery for a living environment. -

United States Air Force and Its Antecedents Published and Printed Unit Histories

UNITED STATES AIR FORCE AND ITS ANTECEDENTS PUBLISHED AND PRINTED UNIT HISTORIES A BIBLIOGRAPHY EXPANDED & REVISED EDITION compiled by James T. Controvich January 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTERS User's Guide................................................................................................................................1 I. Named Commands .......................................................................................................................4 II. Numbered Air Forces ................................................................................................................ 20 III. Numbered Commands .............................................................................................................. 41 IV. Air Divisions ............................................................................................................................. 45 V. Wings ........................................................................................................................................ 49 VI. Groups ..................................................................................................................................... 69 VII. Squadrons..............................................................................................................................122 VIII. Aviation Engineers................................................................................................................ 179 IX. Womens Army Corps............................................................................................................ -

Middle Years (6-9) 2625 Books

South Australia (https://www.education.sa.gov.au/) Department for Education Middle Years (6-9) 2625 books. Title Author Category Series Description Year Aus Level 10 Rules for Detectives MEEHAN, Adventure Kev and Boris' detective agency is on the 6 to 9 1 Kierin trail of a bushranger's hidden treasure. 100 Great Poems PARKER, Vic Poetry An all encompassing collection of favourite 6 to 9 0 poems from mainly the USA and England, including the Ballad of Reading Gaol, Sea... 1914 MASSON, Historical Australia's The Julian brothers yearn for careers as 6 to 9 1 Sophie Great journalists and the visit of the Austrian War Archduke Franz Ferdinand aÙords them the... 1915 MURPHY, Sally Historical Australia's Stan, a young teacher from rural Western 6 to 9 0 Great Australia at Gallipoli in 1915. His battalion War lands on that shore ready to... 1917 GARDINER, Historical Australia's Flying above the trenches during World 6 to 9 1 Kelly Great War One, Alex mapped what he saw, War gathering information for the troops below him.... 1918 GLEESON, Historical Australia's The story of Villers-Breteeneux is 6 to 9 1 Libby Great described as wwhen the Australians held War out against the Germans in the last years of... 20,000 Leagues Under VERNE, Jules Classics Indiana An expedition to destroy a terrifying sea 6 to 9 0 the Sea Illustrated monster becomes a mission involving a visit Classics to the sunken city of Atlantis... 200 Minutes of Danger HEATH, Jack Adventure Minutes Each book in this series consists of 10 short 6 to 9 1 of Danger stories each taking place in dangerous situations. -

“What Is That?” Off in the Dark, a Frightening, Glowing Shape Sailed Across the Ocean Like a Ghost

The moon shined down on the Windcatcher as the great clipper ship sailed through the cold waters of the southern Pacific Ocean. The year was 1849, and the Windcatcher was carrying passengers and cargo from San Francisco to New York City. The Windcatcher was one of the fastest ships on the seas. She was now sailing south, near Chile in South America. She would soon enter the dangerous waters near Cape Horn. Then she would sail into the Atlantic Ocean and move north to New York City. Suddenly, one of the sailors yelled to the crew. “Look!” he cried. “What is that?” Off in the dark, a frightening, glowing shape sailed across the ocean like a ghost. The captain and some of his men moved to the front of the ship to look. As soon as the captain saw the strange sight, he knew what it was. “The Flying Dutchman,” he said softly. The captain looked worried and lost in his thoughts. “What is the Flying Dutchman?” asked one of the sailors. 2 3 Pirates often captured the ships when the crew resisted, they Facts about Pirates and stole the cargo without were sometimes killed or left violence. Often, just seeing at sea with little food or water. the pirates’ flag and hearing Other times, the pirates took A pirate is a robber at sea who great deal of valuable cargo their cannons was enough to the crew as slaves, or the crew steals from other ships out being shipped across the make the crew of these ships became pirates themselves! at sea. -

Equivalent Uranium and Selected Minor Elements in Magnetic Concentrates from the Candle Quadrangle, Solomon Quadrangle, and Elsewhere in Alaska

Equivalent Uranium and Selected Minor Elements in Magnetic Concentrates from the Candle Quadrangle, Solomon Quadrangle, and Elsewhere in Alaska GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1135 Equivalent Uranium and Selected Minor Elements in Magnetic Concentrates from the Candle Quadrangle, Solomon Quadrangle, and Elsewhere in Alaska By KUO-LIANG PAN, WILLIAM C. OVERSTREET, KEITH ROBINSON, ARTHUR E. HUBERT, and GEORGE L. CRENSHAW GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1135 An evaluation of magnetic concentrates as a medium for geochemical exploration in artic and subartic regions UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASH INGTON: 1 980 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR CECIL D. ANDRUS, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY H. William Menard, Director Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Main entry under title: Equivalent uranium and selected minor elements in magnetic concentrates from the Candle quadrangle, Solomon quadrangle, and elsewhere in Alaska. (Geological Survey Professional Paper 1135) Bibliography: p. 103 Supt. of Docs, no.: I 19.16:1135 I. Geochemical prospecting Alaska. 2. Ore-deposits Alaska. I. Pan, Kuo-liang. II. Title: Magnetic concentrates from the Candle quadrangle, Solomon quadrangle, and elsewhere in Alaska. III. Series: United States Geological Survey Professional Paper 1135. TN270.E78 622'.13*09798 79-607131 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 CONTENTS Page Page 1 Distribution of the elements— Continued Introduction--™™-----™™-™--™----™ 2 Candle quadrangle results— Continued 2 51 3 58 3 59 3 Cobalt and nickel —————————————————— 59 3 Indium and thallium ————————————————— 64 xVcLuCLOiuiZcLvion — — —- •— —««—«-•-«— —••«--»--•--«—•-•--•—-••—-«- 3 64 Analytical procedures and reliability of the chemical data — -- 3 65 3 69 16 77 Eight elements by atomic absorption ——— - ——————— 16 7,7 j. -

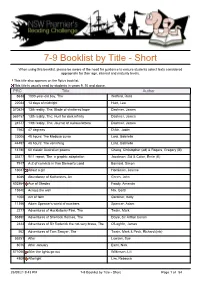

7-9 Booklist by Title - Short

7-9 Booklist by Title - Short When using this booklist, please be aware of the need for guidance to ensure students select texts considered appropriate for their age, interest and maturity levels. This title also appears on the 9plus booklist. This title is usually read by students in years 9, 10 and above. PRC Title Author 5638 1000-year-old boy, The Welford, Ross 22034 13 days of midnight Hunt, Leo 570824 13th reality, The: Blade of shattered hope Dashner, James 569157 13th reality, The: Hunt for dark infinity Dashner, James 24577 13th reality, The: Journal of curious letters Dashner, James 7562 47 degrees D'Ath, Justin 23006 48 hours: The Medusa curse Lord, Gabrielle 44497 48 hours: The vanishing Lord, Gabrielle 14780 60 classic Australian poems Cheng, Christopher (ed) & Rogers, Gregory (ill) 33477 9/11 report, The: a graphic adaptation Jacobson, Sid & Colon, Ernie (ill) 7917 A-Z of convicts in Van Diemen's Land Barnard, Simon 16047 About a girl Horniman, Joanne 8086 Abundance of Katherines, An Green, John 602864 Ace of Shades Foody, Amanda 15540 Across the wall Nix, Garth 1058 Act of faith Gardiner, Kelly 11356 Adam Spencer's world of numbers Spencer, Adam 2277 Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, The Twain, Mark 55890 Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, The Doyle, Sir Arthur Conan 2444 Adventures of Sir Roderick the not-very brave, The O'Loghlin, James 562 Adventures of Tom Sawyer, The Twain, Mark & Peck, Richard (intr) 55251 After Lawson, Sue 8076 After January Earls, Nick 571050 After the lights go out Wilkinson, Lili 4809 Afterlight Lim, -

Roger Ebert's

The College of Media at Illinois presents Roger19thAnnual Ebert’s Film Festival2017 April 19-23, 2017 The Virginia Theatre Chaz Ebert: Co-Founder and Producer 203 W. Park, Champaign, IL Nate Kohn: Festival Director 2017 Roger Ebert’s Film Festival The University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign The College of Media at Illinois Presents... Roger Ebert’s Film Festival 2017 April 19–23, 2017 Chaz Ebert, Co-Founder, Producer, and Host Nate Kohn, Festival Director Casey Ludwig, Assistant Director More information about the festival can be found at www.ebertfest.com Mission Founded by the late Roger Ebert, University of Illinois Journalism graduate and a Pulitzer Prize- winning film critic, Roger Ebert’s Film Festival takes place in Urbana-Champaign each April for a week, hosted by Chaz Ebert. The festival presents 12 films representing a cross-section of important cinematic works overlooked by audiences, critics and distributors. The films are screened in the 1,500-seat Virginia Theatre, a restored movie palace built in the 1920s. A portion of the festival’s income goes toward on-going renovations at the theatre. The festival brings together the films’ producers, writers, actors and directors to help showcase their work. A film- maker or scholar introduces each film, and each screening is followed by a substantive on-stage Q&A discussion among filmmakers, critics and the audience. In addition to the screenings, the festival hosts a number of academic panel discussions featuring filmmaker guests, scholars and students. The mission of Roger Ebert’s Film Festival is to praise films, genres and formats that have been overlooked. -

Routes to Riches 2015 1 Danielhenryalaska.Com

Routes to Riches 2015 1 danielhenryalaska.com Routes to Riches Daniel Lee Henry [email protected] A ground squirrel robe nearly smothered northern Tlingits’ nascent trust in their newly-landed missionaries. Long-time trading ties with Southern Tutchone and Interior Tlingit funneled wealth to Native residents of the upper Lynn Canal. Luxurious furs from the frigid north brought prices many times that of local pelts. For example, while the coastal red fox fur was worth $1.75 in “San Francisco dollars” in 1883, a Yukon silver fox brought up to $50 (about $1200 in 2015). Several times a year, Tlingit expeditions traversed routes considered secret until local leaders revealed their existence to Russians and Americans in the mid-nineteenth century. A day’s paddle to the upper Chilkat River brought travelers to a trail leading over through barrier coastal mountains into the vast, rolling subarctic Interior. On the eastern route, packers left Dyea at the terminus of Taiya Inlet and slogged a twenty-mile trail to a keyhole pass into lake country that drains into the Yukon River headwaters. The image of prospectors struggling up the “Golden Staircase” to Chilkoot Pass engraved the Klondike gold rush of ‘98 onto the license plates of cultural memory. For centuries, Chilkats and Chilkoots sustained a trading cartel connected by their respective routes. From tide’s edge to the banks of the Yukon River four hundred miles north, Tlingits insisted on customer allegiance. They discouraged Interior trading partners from commerce with anyone but themselves and expressly prohibited economic activity without invitation. The 1852 siege of Fort Selkirk and subsequent expulsion of Hudson’s Bay Company demonstrated the market realities of the Chilkat/Chilkoot cartel. -

Sweet & Lowdown Repertoire

SWEET & LOWDOWN REPERTOIRE COUNTRY 87 Southbound – Wayne Hancock Johnny Yuma – Johnny Cash Always Late with Your Kisses – Lefty Jolene – Dolly Parton Frizzell Keep on Truckin’ Big River – Johnny Cash Lonesome Town – Ricky Nelson Blistered – Johnny Cash Long Black Veil Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain – E Willie Lost Highway – Hank Williams Nelson Lover's Rock – Johnny Horton Bright Lights and Blonde... – Ray Price Lovesick Blues – Hank Williams Bring It on Down – Bob Wills Mama Tried – Merle Haggard Cannonball Blues – Carter Family Memphis Yodel – Jimmy Rodgers Cannonball Rag – Muleskinner Blues – Jimmie Rodgers Cocaine Blues – Johnny Cash My Bucket's Got a Hole in It – Hank Cowboys Sweetheart – Patsy Montana Williams Crazy – Patsy Cline Nine Pound Hammer – Merle Travis Dark as a Dungeon – Merle Travis One Woman Man – Johnny Horton Delhia – Johnny Cash Orange Blossom Special – Johnny Cash Doin’ My Time – Flatt And Scruggs Pistol Packin Mama – Al Dexter Don't Ever Leave Me Again – Patsy Cline Please Don't Leave Me Again – Patsy Cline Don't Take Your Guns to Town – Johnny Poncho Pony – Patsy Montana Cash Ramblin' Man – Hank Williams Folsom Prison Blues – Johnny Cash Ring of Fire – Johnny Cash Ghost Riders in the Sky – Johnny Cash Sadie Brown – Jimmie Rodgers Hello Darlin – Conway Twitty Setting the Woods on Fire – Hank Williams Hey Good Lookin’ – Hank Williams Sitting on Top of the World Home of the Blues – Johnny Cash Sixteen Tons – Merle Travis Honky Tonk Man – Johnny Horton Steel Guitar Rag Honky Tonkin' – Hank Williams Sunday Morning Coming -

47106424.Pdf

-- --~ ~.--=-- Public-data File 86-19 PROSPECT EXAMINATION OF A GOLD-TUNGSTEN PLACER DEPOSIT AT ALDER CREEK VINASALE MOUNTAIN AREA, WESTERN ALASKA By T.K. Bundtzen Alaska Division of Geological and Geophysical Surveys March 1986 THIS DOCUMENT HAS NOT RECEIVED OFFICIAL DGGS REVIEW AND PUBLICATION STATUS. 794 University Avenue, Basement Fairbanks, Alaska 99709 CONTENTS Page Introduction. • . .. .................................... 1 History of the prospect............................................... 1 Geology of Vinasale Mountain............ ........•..................... 3 Geology of Alder Gulch Prospect....................................... 3 Concentrate results................................................. 8 Conclusions and recommendations....................................... 8 References cited...................................................... 10 FIGURES Figure 1. Location of Alder Gulch-Vinasale Mountain area, northwest McGrath Quadrangle, Alaska................................. 2 2. Generalized geologic map of Alder Gulch-Vinasale Mountain area, western Alaska... ...•..........• .....•............... 4 3. Field sketch of Snow Placer Prospect, Alder Gulch, Vinasale Mountain, McGrath Quadrangle...................... 5 TABLES Table 1. Selected analyses of rock and pan-concentrate samples, Alder Gulch, McGrath Quadrangle, Alaska.................... 7 2. Mineralogical identification of pan-concentrates, Alder Gulch, Vinasale Moun tain. ...................•.............. 9 ii PROSPECT EXAMINATION OF A GOLD-TUNGSTEN PLACER DEPOSIT