THE LANGUAGE of the MODHUPUR MANDI (GARO) Vol. II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

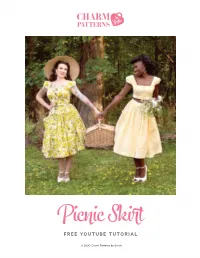

Picnic Skirt FREE YOUTUBE TUTORIAL

Picnic Skirt FREE YOUTUBE TUTORIAL © 2020 Charm Patterns by Gertie SEWING INSTRUCTIONS NOTES: This style can be made for any size child or adult, as long as you know the waist measurement, how long you want the skirt, and how full you want the skirt. I used 4 yards of width, which results in a big, full skirt with lots of gathers packed in. You can easily use a shorter yardage of fabric if you prefer fewer gathers or you’re making the skirt for a smaller person or child. Seam Finishing: all raw edges are fully enclosed in the construction process, so there is no need for seam finishing. Make a vintage-inspired button-front skirt without 5/8-inch (in) (1.5 cm) seam allowances are included on all pattern pieces, except a pattern! This cute design where otherwise noted. can be made for ANY size, from child to adult! Watch CUT YOUR SKIRT PIECES my YouTube tutorial to see 1. Cut the skirt rectangle: the width should be your desired fullness (mine is how it’s done. You can find 4 yards) plus 6 in for the doubled front overlap/facing. The length should be the coordinating top by your desired length, plus 6 in for the hem allowance, plus 5/8 in for the waist seam subscribing to our Patreon allowance. at www.patreon.com/ Length: 27 in. gertiesworld. (or your desired length) Length: + Skirt rectangle 6 in hem allowance xoxo, Gertie 27 in. Cut 1 fabric (or your + desired length) ⅝ in waist seam + Skirt rectangle 6 in hem allowance Cut 1 fabric MATERIALS + & NOTIONS ⅝ in waist seam • 4¼ yds skirt fabric (you Width: 4 yards (or your desired fullness) + 6 in for front overlap may need more or less depending on the size and Length: 27 in. -

Planepack Interview with Rebecca Blackburn September 2017

Planepack interview with Rebecca Blackburn September 2017 Slobodanka: Hello Planepack readers. Welcome to another episode of Planepack. I'm sitting here with Rebecca. We're in the lovely Equinox Café in Deacon. And, Rebecca, tell me you said, you mentioned that you've been travelling light for almost ten years now. How did that all come about? Rebecca: It probably all started when I moved to the U.K. and became, and started travelling regularly. So, off on the weekend, I'd go for a couple of days. And, it was just convenient. Slobodanka: So about travelling light, do you mean with carry on only? or Rebecca: Yes. Slobodanka: So, no hold luggage/ Rebecca: No, no. Just one wheelie bag and one, one cross body handbag. Slobodanka: Handbag, yes. So, how do you plan for a trip like that? Let's say you were going to fly off tomorrow, how would you plan for your wardrobe? What would you take with you? Rebecca: So, it depends on the season. But, there's a few set, set standard items that I take. I, let's start with the sustainability aspects. I would take my Klean Kanteen, which is a thermos, a drink bottle. You can put your tea or coffee in it. And it saves [00:01:23] and it's your cup as well, so, that's number one. And I also take a folding purse, a little handbag. So, for any shopping, for a beach bag, your laundry bag, it's useful. Slobodanka: Multipurpose. Rebecca: Multipurpose, yes. Clothes wise, I take layers. -

Business Professional Dress Code

Business Professional Dress Code The way you dress can play a big role in your professional career. Part of the culture of a company is the dress code of its employees. Some companies prefer a business casual approach, while other companies require a business professional dress code. BUSINESS PROFESSIONAL ATTIRE FOR MEN Men should wear business suits if possible; however, blazers can be worn with dress slacks or nice khaki pants. Wearing a tie is a requirement for men in a business professional dress code. Sweaters worn with a shirt and tie are an option as well. BUSINESS PROFESSIONAL ATTIRE FOR WOMEN Women should wear business suits or skirt-and-blouse combinations. Women adhering to the business professional dress code can wear slacks, shirts and other formal combinations. Women dressing for a business professional dress code should try to be conservative. Revealing clothing should be avoided, and body art should be covered. Jewelry should be conservative and tasteful. COLORS AND FOOTWEAR When choosing color schemes for your business professional wardrobe, it's advisable to stay conservative. Wear "power" colors such as black, navy, dark gray and earth tones. Avoid bright colors that attract attention. Men should wear dark‐colored dress shoes. Women can wear heels or flats. Women should avoid open‐toe shoes and strapless shoes that expose the heel of the foot. GOOD HYGIENE Always practice good hygiene. For men adhering to a business professional dress code, this means good grooming habits. Facial hair should be either shaved off or well groomed. Clothing should be neat and always pressed. -

A New Method of Classification for Tai Textiles

A New Method of Classification for Tai Textiles Patricia Cheesman Textiles, as part of Southeast Asian traditional clothing and material culture, feature as ethnic identification markers in anthropological studies. Textile scholars struggle with the extremely complex variety of textiles of the Tai peoples and presume that each Tai ethnic group has its own unique dress and textile style. This method of classification assumes what Leach calls “an academic fiction … that in a normal ethnographic situation one ordinarily finds distinct tribes distributed about the map in an orderly fashion with clear-cut boundaries between them” (Leach 1964: 290). Instead, we find different ethnic Tai groups living in the same region wearing the same clothing and the same ethnic group in different regions wearing different clothing. For example: the textiles of the Tai Phuan peoples in Vientiane are different to those of the Tai Phuan in Xiang Khoang or Nam Nguem or Sukhothai. At the same time, the Lao and Tai Lue living in the same region in northern Vietnam weave and wear the same textiles. Some may try to explain the phenomena by calling it “stylistic influence”, but the reality is much more profound. The complete repertoire of a people’s style of dress can be exchanged for another and the common element is geography, not ethnicity. The subject of this paper is to bring to light forty years of in-depth research on Tai textiles and clothing in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Laos), Thailand and Vietnam to demonstrate that clothing and the historical transformation of practices of social production of textiles are best classified not by ethnicity, but by geographical provenance. -

Use and Applications of Draping in Turkey's

USE AND APPLICATIONS OF DRAPING IN TURKEY’S CONTEMPORARY FASHION DUYGU KOCABA Ş MAY 2010 USE AND APPLICATIONS OF DRAPING IN TURKEY’S CONTEMPORARY FASHION A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF IZMIR UNIVERSITY OF ECONOMICS BY DUYGU KOCABA Ş IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENTOF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF DESIGN IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES MAY 2010 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences ...................................................... Prof. Dr. Cengiz Erol Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Design. ...................................................... Prof. Dr. Tevfik Balcıoglu Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adaquate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Design. ...................................................... Asst. Prof. Dr. Şölen Kipöz Supervisor Examining Committee Members Asst. Prof. Dr. Duygu Ebru Öngen Corsini ..................................................... Asst. Prof. Dr. Nevbahar Göksel ...................................................... Asst. Prof. Dr. Şölen Kipöz ...................................................... ii ABSTRACT USE AND APPLICATIONS OF DRAPING IN TURKEY’S CONTEMPORARY FASHION Kocaba ş, Duygu MDes, Department of Design Studies Supervisor: Asst. Prof. Dr. Şölen K İPÖZ May 2010, 157 pages This study includes the investigations of the methodology and applications of draping technique which helps to add creativity and originality with the effects of experimental process during the application. Drapes which have been used in different forms and purposes from past to present are described as an interaction between art and fashion. Drapes which had decorated the sculptures of many sculptors in ancient times and the paintings of many artists in Renaissance period, has been used as draping technique for fashion design with the contributions of Madeleine Vionnet in 20 th century. -

Looking at the Past and Current Status of Kenya's Clothing and Textiles

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2018 Looking at the Past and Current Status of Kenya’s clothing and textiles Mercy V.W. Wanduara [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Art Practice Commons, Fashion Design Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Fine Arts Commons, and the Museum Studies Commons Wanduara, Mercy V.W., "Looking at the Past and Current Status of Kenya’s clothing and textiles" (2018). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 1118. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/1118 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings 2018 Presented at Vancouver, BC, Canada; September 19 – 23, 2018 https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/ Copyright © by the author(s). doi 10.32873/unl.dc.tsasp.0056 Looking at the Past and Current Status of Kenya’s clothing and textiles Mercy V. W. Wanduara [email protected] Abstract This paper analyzes and documents traditional textiles and clothing of the Kenyan people before and after independence in 1963. The paper is based on desk top research and face to face interviews from senior Kenyan citizens who are familiar with Kenyan traditions. An analysis of some of the available Kenya’s indigenous textile fiber plants is made and from which a textile craft basket is made. -

Chapter 3 Methodology…

Chapter 3 Methodology… Methodology….. CHAPTER III METHODOLOGY The research being descriptive and analytical in nature, a longitudinal research design was planned to accomplish the framed objectives. The study had been divided into three different phases. The detailed historical research was conducted during the first phase while the second phase included the collection and documentation of the data. Earnest efforts for the preservation and popularization of the traditional royal costumes were made during the third phase of research. The organized research procedure that would be accomplishing the present study is mentioned as follows: 3.1 Selection of topic The present research had started with an inspiring thought of investigator’s master’s dissertation work and experiences. The researcher had seen various researches and documentation of Indian royal costumes especially of princely states of Rajasthan and Gujarat and found that the dearth of information was available on the royal costumes of Kachchh which led researcher towards its investigation. The present research had taken its shape as a researcher came across royal heritage of Kachchh for taking it into the limelight and preserving it in a decent manner for future generation. Moreover, the statement of the problem identified as Documentation of traditional costumes of rulers of Kachchh. The rulers of Kachchh were not as popular as other princely state rulers. The word “royal costume” provides an impression of luxurious fabrics, embellishments, and royalty. There could be the difference in these elements in royal costumes of Kachchh compared to other ruler’s costume. Kachchh’s geographical location has Rajasthan one end and Sindh Pakistan at the other end as neighboring states which could have influenced the costumes. -

Feature Extraction for Image Selection Using Machine Learning

Master of Science Thesis in Electrical Engineering Department of Electrical Engineering, Linköping University, 2017 Feature extraction for image selection using machine learning Matilda Lorentzon Master of Science Thesis in Electrical Engineering Feature extraction for image selection using machine learning Matilda Lorentzon LiTH-ISY-EX--17/5097--SE Supervisor: Marcus Wallenberg ISY, Linköping University Tina Erlandsson Saab Aeronautics Examiner: Lasse Alfredsson ISY, Linköping University Computer Vision Laboratory Department of Electrical Engineering Linköping University SE-581 83 Linköping, Sweden Copyright © 2017 Matilda Lorentzon Abstract During flights with manned or unmanned aircraft, continuous recording can result in a very high number of images to analyze and evaluate. To simplify image analysis and to minimize data link usage, appropriate images should be suggested for transfer and further analysis. This thesis investigates features used for selection of images worthy of further analysis using machine learning. The selection is done based on the criteria of having good quality, salient content and being unique compared to the other selected images. The investigation is approached by implementing two binary classifications, one regard- ing content and one regarding quality. The classifications are made using support vector machines. For each of the classifications three feature extraction methods are performed and the results are compared against each other. The feature extraction methods used are histograms of oriented gradients, features from the discrete cosine transform domain and features extracted from a pre-trained convolutional neural network. The images classified as both good and salient are then clustered based on similarity measures retrieved using color coherence vectors. One image from each cluster is retrieved and those are the result- ing images from the image selection. -

Cambodia Ffl Little OUR COMIC SECTION Mesn FINNEY of the FORCE That Nursery Aroma ' Naocw'a Fiooo Want, I) "Sw I V,Blb Irnla" Fil !Fzf

Cambodia ffl Little OUR COMIC SECTION MesN FINNEY OF THE FORCE That Nursery Aroma ' naocw'A fiooo want, i) "sw i V,BlB IrnlA" fil !fzf TOO MUCH TO BEUEVEI The chauffeur wo holding forth In the village Inn, - "I'us, my young guv'nor rowed for Ooxford a little while back, 'e did." Ill audience stared. "Vus, 'e wins Wired of races," went on the chauffeur, warming to bis task. "An 'e always 'as the name an' the date painted on 'Is scull." But this was too much for one listener. "On 'is skull)" be echoed Indignant-ly- . "I.utnme, 'e must 'ave an 'end Ilk an elephant 1" London Answers, Royal Pagoda at Pnompenh, Cambodia. Snappy A young man walked Into a baker's the Netloaal Oeoarsphle - tiled roofs half hidden (Prepared br magenta- by and asked for two dozen loaves. NCIWMW.&J00PA Yt'o KVWvJ Society, Waahlniloa, P. C.I shop SNIFF , gtnnt pnlms and flowering tropical The looked one of the trees. In a Inclosure on a rhopkeeer surprised. parklike "Have you a tea party onl" be In- CAMBODIA, among Fiance's hill top Is the palace of the kings, sur- la quired. southwest Asia, rounded houses for their multi- . I SMELL AV SOOP by "No, said the man. "I'm working y hodge podge of the unexpec- tudinous feminine retainers. The kings at the menagerie, and the kangaroo j ted It Is land of forests, damp and of Cambodia of the be de- past might has kicked the elephant, so I want to leech-Infeste- of open savannahs, of scribed as monarchs sur- entirely make a bread poultice." wide rice fields and plodding water rounded by women. -

The Flower of Gala Water V Ery Much

THE FLO WER O F GALA WATER . N ovel fl . M S AME L V R . I A E BAR R , ’ “ ” “ A u th o r o Girls o a Feath er T/ze Beads o f f , f ” “ ” Tasmer Frien d O livia etc , , . B WI TH I L L U S T A T I ON S B Y o . K EN DR I CK . Q/ N EW YO R K BE B E ’ S S O N S R O R T O N N R , P U BL I SHERS . m N N O . 1 10 “8 0 5 0 MO NTHLY. S U MORI PTIO N P R I CZ S I ! DO LL RS P K G N U AL OHO IO! OK R I I O , A A ‘ ’ N "l. “A7YI R . ( 74 75 0 5 0 AT I Hl N EW YO RK N . Y . FOOT O 'P IC! AO S ECO D O L O. Al J A NUA RY 1 , , , A The Flower of ala Water G . T CHAP ER I . FL W O F G L W THE O ER A A ATER. W an water fro m th e B o rder h ills ear v o ce fro th e o ld ears D i m y , Th d stant m usic lu lls and st lls y i i , And o ves t o u et tears m q i . A mist o f m em o ry bro o ds and flo ats Th e B o rder W ate rs flo w ; air i ullo f ballad n o t Th e s f es, ” o f lo n a B o rn o ut g go . -

The Hitler Youth Movement, 1933-1945

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1954 The Hitler Youth Movement, 1933-1945 Forest Ernest Barber Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Barber, Forest Ernest, "The Hitler Youth Movement, 1933-1945" (1954). Master's Theses. 905. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/905 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1954 Forest Ernest Barber • A 'fHBSIS BUB.\{l'n'ED TO nm 'ACULT! OJ' THE ClRAOOAft SOHOOL 0' LOIOLA UNlftlSITY IN fA.BfIAL JULFU,z,MSIT OF 'DIS DQUlrw&NTS FOR 'l'BE l'lIGIIIt or *~aO'A~ . A Good Oull,"Y)e For ~ I=-uture TheSIS / 1922. ae .. pwlua,*, fItoa 1IDeae1aer Publ1c High Scbool, leaualaer, Ind1aDlt June, 19lil, and. troa Ju\l.a> tJn1'ftft1t1'. I.Uan.poU., IDd:5u., June, 1945, w1tth the de&:&'ee of Baohelor of Sc1-... FI"OJI 1945 to 19la6 the author taUlh' 1ft aa.-, CUba. r.om 11&16 to 1948 he taught in'tbeU, QfteoeJ ard btoa 1948 tto 19S1 M acted. .. 8D Educa\i.or& Adv.1.r 1n the Troop Infonatial and Ed.... t14n Propaa, tl'D1tecl statM AJ:vlT of OCovpa1d.OD, ~. ForeA Emen ~ 'bepn bJ.a pa4uate durU.. -

VTE Framework: Fashion Technology

Massachusetts Department of Elementary & Secondary Education Office for Career/Vocational Technical Education Vocational Technical Education Framework Business & Consumer Services Occupational Cluster Fashion Technology (VFASH) CIP Code 500407 June 2014 Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education Office for Career/Vocational Technical Education 75 Pleasant Street, Malden, MA 02148-4906 781-338-3910 www.doe.mass.edu/cte/ This document was prepared by the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education Mitchell D. Chester, Ed.D. Commissioner Board of Elementary and Secondary Education Members Ms. Maura Banta, Chair, Melrose Ms. Harneen Chernow, Vice Chair, Jamaica Plain Mr. Daniel Brogan, Chair, Student Advisory Council, Dennis Dr. Vanessa Calderón-Rosado, Milton Ms. Karen Daniels, Milton Ms. Ruth Kaplan, Brookline Dr. Matthew Malone, Secretary of Education, Roslindale Mr. James O’S., Morton, Springfield Dr. Pendred E. Noyce, Weston Mr. David Roach, Sutton Mitchell D. Chester, Ed.D., Commissioner and Secretary to the Board The Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education, an affirmative action employer, is committed to ensuring that all of its programs and facilities are accessible to all members of the public. We do not discriminate on the basis of age, color, disability, national origin, race, religion, sex, gender identity, or sexual orientation. Inquiries regarding the Department’s compliance with Title IX and other civil rights laws may be directed to the Human Resources Director, 75 Pleasant St., Malden, MA 02148-4906. Phone: 781-338-6105. © 2014 Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education Permission is hereby granted to copy any or all parts of this document for non-commercial educational purposes.