DATA REPLICATION and EXTENSION: a STUDY of STRATEGIC BUSINESS PLANNING and VENTURE LEVEL PERFORMANCE Benson Honig

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SEASON TICKET HOLDER © 2006 Mellon Financial Corporation

Make it Last. SEASON TICKET HOLDER © 2006 Mellon Financial Corporation Across market cycles. Over generations. Beyond expectations. The Practice of Wealth Management.® c Wealth Planning • Investment Management • Private Banking Family Office Services • Business Banking • Charitable Gift Services Please contact Philip Spina, Managing Director, at 412-236-4278. mellonprivatewealth.com Investing in the local economy by working with local businesses means helping to keep jobs in the region. It’s how we help to make this a better place to live, to work, to raise a family. And it’s one way Highmark has a helping hand in the places we call home. 3(1*8,16 )$16 ),567 ZZZ)R[6SRUWVFRP 6HDUFK3LWWVEXUJK HAVE A GREATER HAND IN YOUR HEALTH.SM TABLE OF CONTENTS PITTSBURGH PENGUINS Administrative Offices Team and Media Relations One Chatham Center, Suite 400 Mellon Arena Pittsburgh, PA 15219 66 Mario Lemieux Place Phone: (412) 642-1300 Pittsburgh, PA 15219 FAX: (412) 642-1859 Media Relations FAX: (412) 642-1322 2005-06 In Review 121-136 Opponent Shutouts 272-273 2006 Entry Draft 105 Opponents 137-195 2006-07 Season Schedule 360 Overtime 258 Active Goalies vs. Pittsburgh 197 Overtime Wins 259-260 Affiliate Coaches: Todd Richards 12 Penguins Goaltenders 234 Affiliate Coaches: Dan Bylsma 13 Penguins Hall of Fame 200-203 All-Star Game 291-292 Penguins Hat Tricks 263-264 All-Time Draft Picks 276-280 Penguins Penalty Shots 268 All-Time Leaders vs. Pittsburgh 196 Penguins Shutouts 270-271 All-Time Overtime Scoring 260 Player Bios 30-97 Assistant Coaches 10-11 -

Vancouver Canucks 2009 Playoff Guide

VANCOUVER CANUCKS 2009 PLAYOFF GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS VANCOUVER CANUCKS TABLE OF CONTENTS Company Directory . .3 Vancouver Canucks Playoff Schedule. 4 General Motors Place Media Information. 5 800 Griffiths Way CANUCKS EXECUTIVE Vancouver, British Columbia Chris Zimmerman, Victor de Bonis. 6 Canada V6B 6G1 Mike Gillis, Laurence Gilman, Tel: (604) 899-4600 Lorne Henning . .7 Stan Smyl, Dave Gagner, Ron Delorme. .8 Fax: (604) 899-4640 Website: www.canucks.com COACHING STAFF Media Relations Secured Site: Canucks.com/mediarelations Alain Vigneault, Rick Bowness. 9 Rink Dimensions. 200 Feet by 85 Feet Ryan Walter, Darryl Williams, Club Colours. Blue, White, and Green Ian Clark, Roger Takahashi. 10 Seating Capacity. 18,630 THE PLAYERS Minor League Affiliation. Manitoba Moose (AHL), Victoria Salmon Kings (ECHL) Canucks Playoff Roster . 11 Radio Affiliation. .Team 1040 Steve Bernier. .12 Television Affiliation. .Rogers Sportsnet (channel 22) Kevin Bieksa. 14 Media Relations Hotline. (604) 899-4995 Alex Burrows . .16 Rob Davison. 18 Media Relations Fax. .(604) 899-4640 Pavol Demitra. .20 Ticket Info & Customer Service. .(604) 899-4625 Alexander Edler . .22 Automated Information Line . .(604) 899-4600 Jannik Hansen. .24 Darcy Hordichuk. 26 Ryan Johnson. .28 Ryan Kesler . .30 Jason LaBarbera . .32 Roberto Luongo . 34 Willie Mitchell. 36 Shane O’Brien. .38 Mattias Ohlund. .40 Taylor Pyatt. .42 Mason Raymond. 44 Rick Rypien . .46 Sami Salo. .48 Daniel Sedin. 50 Henrik Sedin. 52 Mats Sundin. 54 Ossi Vaananen. 56 Kyle Wellwood. .58 PLAYERS IN THE SYSTEM. .60 CANUCKS SEASON IN REVIEW 2008.09 Final Team Scoring. .64 2008.09 Injury/Transactions. .65 2008.09 Game Notes. 66 2008.09 Schedule & Results. -

Dobber's 2010-11 Fantasy Guide

DOBBER’S 2010-11 FANTASY GUIDE DOBBERHOCKEY.COM – HOME OF THE TOP 300 FANTASY PLAYERS I think we’re at the point in the fantasy hockey universe where DobberHockey.com is either known in a fantasy league, or the GM’s are sleeping. Besides my column in The Hockey News’ Ultimate Pool Guide, and my contributions to this year’s Score Forecaster (fifth year doing each), I put an ad in McKeen’s. That covers the big three hockey pool magazines and you should have at least one of them as part of your draft prep. The other thing you need, of course, is this Guide right here. It is not only updated throughout the summer, but I also make sure that the features/tidbits found in here are unique. I know what’s in the print mags and I have always tried to set this Guide apart from them. Once again, this is an automatic download – just pick it up in your downloads section. Look for one or two updates in August, then one or two updates between September 1st and 14th. After that, when training camp is in full swing, I will be updating every two or three days right into October. Make sure you download the latest prior to heading into your draft (and don’t ask me on one day if I’ll be updating the next day – I get so many of those that I am unable to answer them all, just download as late as you can). Any updates beyond this original release will be in bold blue. -

2007 SC Playoff Summaries

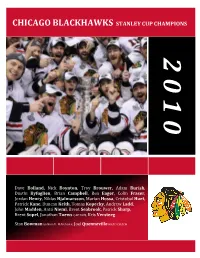

CHICAGO BLACKHAWKS STANLEY CUP CHAMPIONS 2 0 1 0 Dave Bolland, Nick Boynton, Troy Brouwer, Adam Burish, Dustin Byfuglien, Brian Campbell, Ben Eager, Colin Fraser, Jordan Henry, Niklas Hjalmarsson, Marian Hossa, Cristobal Huet, Patrick Kane, Duncan Keith, Tomas Kopecky, Andrew Ladd, John Madden, Antti Niemi, Brent Seabrook, Patrick Sharp, Brent Sopel, Jonathan Toews CAPTAIN, Kris Versteeg Stan Bowman GENERAL MANAGER, Joel Quenneville HEAD COACH © Steve Lansky 2010 bigmouthsports.com NHL and the word mark and image of the Stanley Cup are registered trademarks and the NHL Shield and NHL Conference logos are trademarks of the National Hockey League. All NHL logos and marks and NHL team logos and marks as well as all other proprietary materials depicted herein are the property of the NHL and the respective NHL teams and may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of NHL Enterprises, L.P. Copyright © 2010 National Hockey League. All Rights Reserved. 2010 EASTERN CONFERENCE QUARTER—FINAL 1 WASHINGTON CAPITALS 121 v. 8 MONTRÉAL CANADIENS 88 GM GEORGE McPHEE, HC BRUCE BOUDREAU v. GM PIERRE GAUTHIER, HC JACQUES MARTIN CANADIENS WIN SERIES IN 7 Thursday, April 15 1900 h et on TSN, Versus Saturday, April 17 1900 h et on TSN, Versus MONTREAL 3 @ WASHINGTON 2 OVERTIME MONTREAL 5 @ WASHINGTON 6 OVERTIME FIRST PERIOD FIRST PERIOD 1. MONTREAL, Mike Cammalleri 1 (Andrei Markov, Andrei Kostitsyn) 12:36 PPG 1. MONTREAL, Brian Gionta 1 (Scott Gomez) 1:00 2. WASHINGTON, Joe Corvo 1 (Eric Belanger, Jason Chimera) 15:33 2. MONTREAL, Andrei Kostitsyn 1 (unassisted) 7:58 3. WASHINGTON, Eric Fehr 1 (Tomas Fleischmann) 10:21 Penalties ― Bergeron M 0:52, Semin W 6:01, Backstrom W 12:11, Pouliot M 12:53 Penalties ― None SECOND PERIOD NO SCORING SECOND PERIOD 4. -

Hockey Camp Sweden Hockey Camp Sweden

HOCKEYHOCKEY CAMPCAMP SWEDENSWEDEN 2 0 Y E A r S O f P r O f ess i ona l t r A i N i N g 2012 H ockey C amp S weden Hockey PlayersBorn 1994–97 ages 15–18 High level training Camp EMPHASiS ON tECHNiqUES, SOME HigHligHtS frOM OUr SHOOtiNg, SCOriNg, SKAtiNg AND ONE WEEK PrOgrAM: ● 3 hours of intense on-ice instruction ● Offensive and defensive checking stra- CHECKiNg StrAtEgY daily tegy ● Advanced Power Skating sessions ● Off-ice training to develop physical in rimbo 30 km from ● Shooting techniques: backhand, wrists, strength, agility, flexibility and quick- snap, short slapshot and deking ness ● Arlanda airport in ● Puck control: dribbles, fakes, passes and Dryland training on individual skills Stockholm, Sweden, you protection with puck ● ● Winning all one-on-one situations Lectures, winning attitude, video and will learn the best of personal athletic profile ● Individual defence concepts with ● hockey being coached by special applications for defencemen and Off-ice training to develop technique forwards and coordination professionals from ● ● Individual offensive play with special Program for goaltenders designed by Sweden, russia, Canada applications for defencemen and for- special instructors and USA during July 1–7, wards ● Games 8–14 and 15–21, 2012. there are special coaches for defence men, goalies and forwards. And instructors who can teach you to shoot and skate better! H ockey C amp S weden H ockey C amp S weden WHEN, WHErE AND HOW? HOCKEY CAMP A tYPiCAl DAY fOr PlayerS 15–18 YEArS OlD: JUlY 1–7, 8–14 AND 15–21, 2012 SWEDEN At tHE CAMP HOCKEY CAMP SWEDEN Kindly use the application form on our Hockey Camp Sweden 2012 is located web site to register at Hockey Camp Professional training from in Rimbo about 30 kilometers from Sweden: Arlanda International Airport, Stock- www.hockeycamp-sweden.com Swedish, russian, Canadian holm. -

Swedish Olympic Team PYEONGCHANG 2018

Swedish Olympic Team PYEONGCHANG 2018 MEDIA GUIDE - SWEDISH OLYMPIC TEAM, PYEONGCHANG 2018 3 MEDIA GUIDE SWEDEN This Booklet, presented and published by the Swedish Olympic Committee is intended to assist members of the media at the Games of the XXXII Olympiad. Information is of January 2018. For late changes in the team, please see www.sok.se. Location In northern Europe, on the east side of the Scandi- navian Peninsula, with coastline on the North and Baltic seas and the Gulf of Bothnia. Neighbours Norway on the East. Mountains along Northwest border cover 25 per cent of Sweden. Flat or rolling terrain covers central and southern areas which includes several large lakes. Official name: Konungariket Sverige (Kingdom of Sweden). Area: 447 435 km2 (173 732 sq. miles). Rank in the world: 57. Population: 10 093 734 Capital: Stockholm Form of government: Constitutional monarchy and parliamentary state with one legislative house (Parliament with 349 seats). Current constitution force since January 1st, 1975. Chief of state: King Carl XVI Gustaf, since 1973. Head of government: Prime Minister Stefan Löfven, since 2014. Official language: Swedish. Monetary unit: 1 Swedish krona (SEK) = 100 öre. (Valuation January 2018). 1 USD= 8,17 SEK, 1 EUR= 9,83 SEK. MEDIA GUIDE - SWEDISH OLYMPIC TEAM, PYEONGCHANG 2018 4 ANSVARIG UTGIVARE Lars Markusson, + 46 (0) 70 568 90 31, [email protected] ADRESS Sveriges Olympiska Kommitté, Olympiastadion, Sofiatornet, 114 33 Stockholm TEL 08-402 68 00 www.sok.se LAYOUT Linda Sandgren, SOK TRYCK Elanders 2018 MEDIA GUIDE - SWEDISH OLYMPIC TEAM, PYEONGCHANG 2018 5 CONTENT SWEDISH OLYMPIC COMMITTEE 6 INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC MOVEMENT 8 SWEDEN AND THE OLYMPIC GAMES 9 SWEDISH MEDALLISTS 10 CDM:S AND FLAG BEARERS 18 SWEDEN AT PREVIOUS WINTER GAMES 19 OLYMPIC VENUES 20 COMPETITION SCHEDULE 22 SWEDISH OLYMPIC TEAM 24 MEDIA GUIDE - SWEDISH OLYMPIC TEAM, PYEONGCHANG 2018 6 SWEDISH OLYMPIC COMMITTEE The Swedish Olympic Committee, SOC, is the supreme authority of Sweden in all Olym- pic matters. -

Team Sweden Has Won Eight World Championship Gold Medals

TEAM SWEDEN HAS WON EIGHT WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP GOLD MEDALS Tre Kronor has won seven World Championship Gold Medals during the years, 1953, 1957, 1962, 1987, 1991, 1992, 1998 and 2006. This is what happened when we won: 1953 in Zürich, Switzerland This became a tournament where important nations were missing. USA was forbidden to come. They were banned because of fighting in a game in Basel the year before. Canada decided to show sympathy for USA and didn’t show up either. It became even less teams in the tournament when Czechoslovakia suddenly went home. The reason was that their president Gottwaldow died and national mourning was declared. The Czechoslovakian government forbid sport competitions and therefore Team Czechoslovakia had nothing else to do than return home during the tournament. It was the first time Team Sweden played with three lines instead of two. The result was successful. Team Sweden won the Gold Medal before West Germany (Silver Medal) and Switzerland (Bronze Medal). So in the end all three participating teams got one medal each. Göte Blomqvist, from Södertälje SK, was best scorer in Team Sweden with seven goals. Team Sweden’s results: Czechoslovakia (before they went home) 5-3, Switzerland 9-2 and 9-1, West Germany 8-6 and 12-2. 1957 in Moscow, Soviet Union Nobody expected success from the young team with seven World Championship rookies that went to Moscow. Even important representatives from media decided to stay at home. But team Sweden played well and the results went our way. Before the last game against the Soviet Union a tied game would be enough to win the whole tournament. -

Dags För Foppas Expertdebut I Eurosport

2016-10-05 08:44 CEST Dags för Foppas expertdebut i Eurosport Med två Stanley Cup-titlar, två OS-guld och två VM-guld är Peter Forsberg en av de största stjärnorna i svensk idrottshistoria. Nu startar Foppa ny karriär som hockeyexpert när CHL-slutspelet avgörs i Eurosport. Debuten gör Peter Forsberg i Eurosport 1 den 11 oktober då Djurgården tar emot finska KalPa i slutspelet i Champions Hockey League. Tillsammans med förre landslagskollegan Mikael Samuelsson är Forsberg en del i Eurosports CHL-satsning med programledare Isabel Boltenstern och expert Daniel Rudslätt i spetsen. Frågan är om Foppa blir lika hård i kommentarerna som han var på isen, nu när sju svenska lag finns kvar i slutspelet. - Jag är en ganska snäll människa men vi får väl se, jag ska vara ärlig åtminstone. CHL behöver mer känslor och rivalitet vilket jag tror kommer efter ett par år. Tanken att de bästa lagen från Europa ska göra upp om titeln är bra, det behövs verkligen. Peter Forsberg är tillsammans med Anja Pärson och Per Elofsson tunga profiler i Discovery Networks Swedens OS-satsning där Pyeongchang 2018 är först ut. Med två OS-guld vet Foppa vad som krävs för att lyckas, även om rollen är ny. - Det känns jättekul att jobba mot OS, jag är väldigt exalterad! Det ska bli spännande att se hockeyn från ett annat perspektiv och få en ny utmaning i livet. Jag vet inte vad som krävs för att bli kallad expert egentligen...(skratt). Men det ska bli kul att få den rollen och få dela med sig av mina tankar om hockey. -

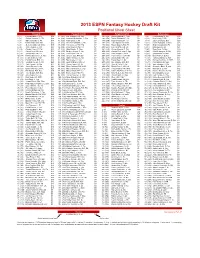

2013 ESPN Fantasy Hockey Draft Kit Positional Cheat Sheet Forwards Forwards (Ctn'd) Forwards (Ctn'd) Defensemen 1

2013 ESPN Fantasy Hockey Draft Kit Positional Cheat Sheet Forwards Forwards (ctn'd) Forwards (ctn'd) Defensemen 1. (1) Evgeni Malkin, C, Pit $39 81. (123) Loui Eriksson, LW, Dal $8 195. (256) David Legwand, C, Nsh $0 1. (8) Erik Karlsson, D, Ott $33 2. (2) Steven Stamkos, C, TB $38 82. (124) Jonathan Huberdeau, C, Fla $8 196. (258) Derick Brassard, C, Cls $0 2. (12) Kris Letang, D, Pit $32 3. (3) Sidney Crosby, C, Pit $37 83. (125) Patrik Elias, C, NJ $8 197. (260) Nazem Kadri, LW, Tor $0 3. (17) Zdeno Chara, D, Bos $29 4. (4) Daniel Sedin, LW, Van $36 84. (126) Vincent Lecavalier, C, TB $8 198. (261) Carl Hagelin, LW, NYR $0 4. (22) Dustin Byfuglien, D, Win $26 5. (6) Alex Ovechkin, LW, Was $35 85. (130) Kris Versteeg, RW, Fla $7 199. (262) Pascal Dupuis, RW, Pit $0 5. (28) Brian Campbell, D, Fla $24 6. (9) John Tavares, C, NYI $33 86. (131) Peter Mueller, RW, Fla $7 200. (263) Eric Tangradi, LW, Pit $0 6. (37) Dan Boyle, D, SJ $21 7. (10) Claude Giroux, C, Phi $33 87. (132) Mike Ribeiro, C, Was $7 201. (265) Gustav Nyquist, C, Det $0 7. (43) Ryan Suter, D, Min $20 8. (11) Corey Perry, RW, Ana $32 88. (133) Stephen Weiss, C, Fla $7 202. (266) Roman Cervenka, C, Cgy $0 8. (49) Alex Pietrangelo, D, StL $19 9. (13) James Neal, RW, Pit $31 89. (134) Chris Kunitz, LW, Pit $7 203. (267) Chris Kreider, C, NYR $0 9. -

HOCKEY OPERATIONS #29: Thomas Bordeleau / #30: Martin Chromiak

2020 COLUMBUS BLUE JACKETS NHL DRAFT GUIDE The 2020 Columbus Blue Jackets Draft Guide was produced by the club’s Communications Department. We hope that you will find it helpful in your contin- ued coverage of our hockey club. Should you have any questions or need assistance, please feel free to contact one of us at any time. We appreciate your coverage of Blue Jackets hockey. The 2020 NHL Draft will be held virtually with the first round beginning at 7 p.m. ET on Tuesday, October 6 and rounds 2-7 beginning at 11:30 a.m. ET on Wednesday, October 7. Communications Contacts Todd Sharrock, VP of Communications & Team Services (614) 246-4157 [email protected] @ToddSharrock Glenn Odebralski, Manager of Communications (614) 246-0288 [email protected] @GlennOdebralski TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents................................................................................. 1 #23: Justin Sourdif / #24: Ty Smilanic ................................................. 25 Staff Directory ..................................................................................... 2 #25: Daemon Hunt / #26: Jake Neighbours ........................................ 26 #27: Ryan O’Rourke / #28: Jan Mysak ................................................ 27 HOCKEY OPERATIONS #29: Thomas Bordeleau / #30: Martin Chromiak ................................. 28 General Manager Jarmo Kekalainen Bio .............................................. 3 European Skaters Hockey Operations Bios/Scouting Staff ............................................. -

PDF Converter-Ecvgcwej5743

Tue Aug 23 09:20am EDT The Juice: Already? Astros officially eliminated from postseason By 'Duk Nine innings and nine items to get you going. Ladies and gentleman of the Stew, take a sip of morning Juice. 1. Be gone with you! We're not even among a week of the calendar flipping to September,merely the Houston Astros have additionally tumbled into an early grave. A 9-5 detriment to the Colorado Rockies, combined with Milwaukee's doubleheader split in Pittsburgh earned Brad Mills'(notes) cluster a mathematical elimination from the 2011 playoff chase. And always meantime we tin still clothes white to summer picnics! For shame,nfl jersey. The Astros are currently 42-86 and on pace as 109 losses. That'd be the maximum in baseball since the 2004 Arizona Diamondbacks lost 111 games. In case you're wondering who's next to get the assured go- ahead as booking tee times, the Baltimore Orioles' elimination digit is nine,while the Florida Marlins' measures by eleven. 2. Slumping snakes: Speaking of the D'Backs,2012 nfl jersey, this isn't how you unseat a defending champion. Despite San Francisco's recent woes Arizona is managing to do them an aggravate A 4-1 loss to the Washington Nationals aboard Monday night brought the team's detriment streak to six,notwithstanding they still own a one-game guide in the NL West over the Giants. They've scored only seven runs in their last six games. 3. V is as Victory: ... and too Justin Verlander(notes), who became the 1st 19-game winner in the majors by going seven solid innings in Detroit's 5-2 conquer over the Tampa Bay Rays. -

2010 NHL Working Ranking File

10-team cheat sheet with auction values Forwards Forwards (ctn'd) Forwards (ctn'd) Defensemen (ctn'd) 1. Alex Ovechkin, LW, Was $33 100. David Booth, LW, Fla $8 233. Evander Kane, C, Atl $0 187. Marek Zidlicky, D, Min $2 2. Sidney Crosby, C, Pit $32 102. Jason Arnott, C, NJ $8 234. Mike Modano, C, Det $0 188. Joe Corvo, D, Car $2 3. Nicklas Backstrom, C, Was $29 103. Jason Pominville, RW, Buf $8 237. Rob Schremp, C, NYI $0 191. Keith Yandle, D, Pho $2 4. Steven Stamkos, C, TB $27 105. Brenden Morrow, LW, Dal $8 238. Tyler Seguin, C, Bos $0 193. Dennis Wideman, D, Fla $2 5. Henrik Sedin, C, Van $26 107. Jamie Langenbrunner, RW, NJ $8 241. Patrik Berglund, C, StL $0 195. Ryan Suter, D, Nsh $2 6. Daniel Sedin, LW, Van $25 108. Wojtek Wolski, LW, Pho $8 242. Tomas Fleischmann, RW, Was $0 197. Dennis Seidenberg, D, Bos $1 7. Dany Heatley, LW, SJ $24 110. Scott Gomez, C, Mon $8 243. Magnus Paajarvi-Svensson, LW, Edm $0 199. Jamie McBain, D, Car $1 8. Alexander Semin, LW, Was $24 111. Claude Giroux, RW, Phi $8 246. Josh Bailey, C, NYI $0 200. Kris Letang, D, Pit $1 10. Zach Parise, LW, NJ $23 114. Mike Knuble, RW, Was $8 247. Nikolai Kulemin, LW, Tor $0 202. Jason Demers, D, SJ $1 11. Evgeni Malkin, C, Pit $22 115. Mikael Samuelsson, RW, Van $8 249. Paul Kariya, LW, StL $0 203. Paul Martin, D, Pit $1 13. Pavel Datsyuk, C, Det $21 117.