Science & Technology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History and Aesthetics in Suspension Bridges

History and Aesthetics in Suspension Bridges 1 6-01 john a roebling_150dpi.jpg Today we trace the evolution of steel bridge design from its first American innovator, JA Roebling up through 1930’s New York In the 30’s in New York, despite hard economic times, many huge structures were erected 2 6-02 empire state building_150dpi.jpg The Empire State Building, tallest in the world About which more later 3 6-03 george washington bridge_150dpi.jpg The GW Bridge, longest suspension span by a factor of two, and 4 6-04 bayonne bridge_150dpi.jpg The Bayonne Bridge, longest arch span in the world, barely surpassing the Sydney Harbor Bridge 5 6-05 othmar ammann_150dpi.jpg These last two were both designed by Othmar H. Ammann, the greatest bridge artist to use steel as his material Ammann was born in Bern, graduated 1902 from ETH and 1904 to USA. Worked from 1912-23 for Lindenthal He would study under Karl Ritter protégé of Carl Cullmann The Swiss were uniquely able to mediate the scientific rigor of the germans with the design elegance of the French 6 6-06 hell gate and triborough bridges_150dpi.jpg The story of Ammann and the GWB begins with Gustav Lindenthal, the dean of American bridge engineers Ammann had cut his teeth as design assistant to Gustav Lindenthal at the Hellgate Bridge The last great bridge of the railroad bridges. From here on the great bridges would carry road traffic rather than trains Here we see two bridges, Hellgate and Triborough, on which Ammann would work, but not express his aesthetic vision 7 6-08 gustav lindenthal_150dpi.jpg Hellgate designer Lindnethal Born in Brunn in Austria, now Brno in the Czech Republic Designed a bridge at Pittsburgh, a lenticular truss to replace Roebling’s Smithfield St. -

Gustav Lindenthal's Little Hell Gate Rail Bridge

ear the flagship Hell Gate Bridge (STRUCTURE, October 2013), and crossing a former inlet between Historic Wards and Randalls Islands, stands NGustav Lindenthal’s still-in-service 1915 Little Hell Gate Bridge; four unique skewed-deck truss structures spans of reverse parabolic bowstring arches. They are visually striking, sited as they are above flat significant structures of the past land and below miles of high plate-girder via- ducts. The total length between centers of the abutments is 1153.5 feet. Four-rail tracks operate on the 60-foot wide deck (Figure 1). Figure 1. Flanked by viaduct spans, the century-old, The War Department at that time regulated water- still in service, distinctive Little Hell Gate Bridge ways and, as this arm of the East River was only a reverse bowstring arch-spans suspend; with the Hell few feet deep and would not carry maritime traffic, it Gate and Triborough Bridges beyond. HAER NY 121- ® granted approvals in 1906 and 1912 for piers in the 16, Weinstein, Photographer, 1996. inlet and the use of falsework for the construction. Later, landfill from the Triborough Bridge project Formwork consisted of two-inch thick, ship- (Ammann, 1937) entirely filled the inlet. lap timber sheeting under four by eight-inch studs, held with wales and then bolted end-to- Timber and Masonry end for tensioning against leakage. The river for the Piers pier shaftCopyright forms were barrel-hooped. The Portland cement concrete piers bear at four tons On Randalls Island, con- per square foot on foundations of hard strata, typically crete was mixed on-site in Gustav Lindenthal’s Little mica schist, encountered at a shallow depth of about a hopper below ground Hell Gate Rail Bridge 12-15 feet below mean low water. -

Bayonne Bridge Lesson Plan

The Bayonne Bridge: The Beautiful Arch Resources for Teachers and Students [Printable and Electronic Versions] The Bayonne Bridge: The Beautiful Arch Resources for Teachers And Students [Printable and Electronic Versions] OVERVIEW/OBJECTIVE: Students will be able to understand and discuss the history of NOTES: the Bayonne Bridge and use science and engineering basics • Key words indicated in to investigate bridge design and test an arch bridge model. Bold are defined in call- out boxes. TARGET GRADE LEVEL: • Teacher-only text Fourth grade instruction, adaptable to higher levels as indicated with Italics. desired in the subjects of Social Studies and Engineering. FOCUS: In Part I, students learn about history of the Bayonne Bridge including the many engineering challenges encountered during the project and the people who helped overcome those challenges. In Part II, students learn engineering concepts to understand how bridges stay up and use these concepts to complete activities on bridge design before applying these concepts to theorize how the Bayonne Bridge works. MATERIALS: • Part I: DVD of “The Bayonne Bridge Documentary” • Part II: 2–4 heavy textbooks or 2 bricks per group; 2 pieces of “cereal box” cardboard or similar, 12 x 8 in; weights (anything small that can be stacked on the structure); red and blue marker, crayon or colored pencil for each student or group. The Bayonne Bridge: The Beautiful Arch Contents Teacher Materials | Part I: History of the Bayonne Bridge . T-1 Teacher Materials | Part II: Bridge Engineering . T-7 Student Materials | Part I: History of the Bayonne Bridge . S-1 Student Materials | Part II: Bridge Engineering . -

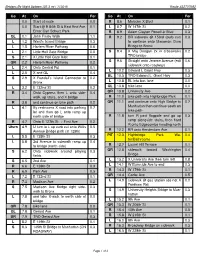

Roadway Open Cuts: Queens

666...111333::: RRROOOAAADDDWWWAAAYYY OOOPPPEEENNN CCCUUUTTTSSS::: QQQUUUEEEEEENNNSSS 111444 cccooorrrrrriiidddooorrrsss,,, 111000777 pppaaarrrccceeelllsss,,, 111444888...33000 aaacccrrreeesss 383 Corridor Description Parcels Total Code Acres Q01 Brooklyn-Queens Expressway: West Of 65th Street-North Of Broadway 9 7.36 Q02 Brooklyn-Queens Expressway: South Of Bulova Avenue-North Of 49th Street 3 2.01 Q03 Grand Central Parkway: 31st Street-West Of Ditmars Boulevard 13 17.56 Q04 Queens-Midtown Tunnel: Queens Portal 1 0.25 Q05 Long Island Expressway: West And East Of Greenpoint Avenue 2 0.76 Q06 Long Island Expressway: West Of Hamilton Place-East Of 69th Street 4 6.01 Q07 Long Island Expressway: Theoretical Extension Of 187th Street-Springfield Boulevard 10 6.53 Q08 Van Wyck Expressway: Union Turnpike-South Of 133rd Avenue, 22 34.34 and North Of Manton Street-Northeast Of Queens Boulevard Q09 Cross Island Parkway: West Of 147th Street-East Of Utopia Parkway 10 24.95 Q10 Grand Central Parkway: Northwest Of Union Turnpike-East Of 168th Street 7 14.24 Q11 Jackie Robinson Parkway: Southwest And Northeast Of Queens Boulevard 2 0.41 Q12 Clearview Expressway: South Of Horace Harding Expressway North-North Of 26th Avenue 15 31.88 Q13 Flushing Avenue: 56th Street-Rust Street, Maspeth 6 0.99 Q14 Queens Boulevard: West of Woodhaven Boulevard-East of I-495 service road 3 1.01 384 QQQ000111::: BBBRRROOOOOOKKKLLLYYYNNN---QQQUUUEEEEEENNNSSS EEEXXXPPPRRREEESSSSSSWWWAAAYYY::: WWWEEESSSTTT OOOFFF 666555TTTHHH SSSTTTRRREEEEEETTT---NNNOOORRRTTTHHH OOOFFF BBBRRROOOAAADDDWWWAAAYYY -

The GREAT BRIDGE ARCHITECT/DESIGNER

1 The GREAT BRIDGE ARCHITECT/DESIGNER (Othmar Ammann left his Mark on New York City) Steve Krar Perhaps no twentieth-century engineer has left a more visible mark on a major city than had Othmar Ammann on New York. His five major bridges bear much of the enormous traffic flow to and from the city. They are beautiful and efficient structures, for Ammann achieved an uncommon harmony of visual elegance, simplicity, and power with practical design. Othmar Ammann Born in Switzerland, Othmar Ammann attended the Federal Polytechnic Institute of Zurich and earned an engineering degree in 1902. He had an interest in and an aptitude for mathematics and physics. Coming to the United States In August of 1907 the Quebec Bridge over the St. Lawrence River in Canada collapsed while under construction. Ammann offered to assist in the investigation of the collapse; his well-written report on the disaster earned him respect in his profession. The Hell Gate Bridge In 1912 Ammann was a chief assistant to Gustav Lindenthal, who was preparing for the great railroad bridge between Queens and Wards Island known as Hell Gate. The span was large; the ultimate design would be the longest arch-type bridge in the world. The rapid tidal currents made impossible to erect scaffolding in the river. The Hell Gate Bridge opened in 1917 and its design communicates rigidity with almost all its weight and outward thrust carried by the lower of the two steel arches. Hudson River Bridge Ammann’s final design for the Hudson River bridge called for a 3,500-foot span twice the length of any existing bridge, between Fort Lee in New Jersey and 179 Street in Manhattan. -

1 Interview with Princeton University Professor David Billington For

Interview with Princeton University Professor David Billington for Program Three: “Bridging New York” Note: This transcript is from a videotaped interview for the “Bridging New York” segment of “Great Projects.” It has been edited lightly for readability. David Billington (DB): It’s a curious fact that at least the three leading bridge designers in our tradition in America were immigrants from German-speaking countries: Roebling, John Roebling then, in 1831, Gustav Lindenthal, who came over in 1875, and Othmar Ammann in 1904. And a major reason for that, I think, is their educational system. The fact that, at least in Roebling’s case and in Ammann’s case, they were trained in the very best engineering schools at the time. Those schools also, particularly in Ammann’s case, emphasized strongly the study of completed structures rather than just merely the tools of analysis, as so often happens in engineering schools. And so when, during Ammann’s education his head was filled with images of all kinds of structures and, therefore, he came with a strong urge to design large-scale works. So did Roebling. DB: What they found when they came to this country, these immigrant engineers, in fact in a way what drew them to the country in the first place was the wide expanse of the country which meant the wide or the great possibilities in building. And in the sense of New York City, for example, this river, the Hudson River, which was an extraordinarily wide river close to a major city. So that this was a great challenge. -

Go at on for 0.0 Start of Route 0.0 0.0 Start @ E 84Th St & East End

Bridges By Night Uptown (25.3 mi / 1130 ft) Route #32737682 Go At On For Go At On For 0.0 Start of route 0.0 R 8.6 Malcolm X Blvd 0.1 0.0 Start @ E 84th St & East End Ave. 0.1 L 8.7 W 147th St 0.2 Enter Carl Schurz Park R 8.9 Adam Clayton Powell Jr Blvd 0.3 QL 0.1 John Finley Walk 1.1 R 9.2 BR sidewalk @ 153rd (curb cut) 0.3 L 1.2 Ward’s Island Bridge 0.3 to continue onto Macombs Dam L 1.5 Harlem River Pathway 0.6 Bridge to Bronx L 2.1 Little Hell Gate Bridge 0.0 S 9.4 X Maj Deegan 2x in crosswalks 0.2 S 2.1 X Little Hell Gate Inlet 0.1 TRO bridge QR 2.2 Harlem River Pathway 0.2 S 9.6 Straight onto Jerome Avenue (exit 0.6 sidewalk onto roadway) L 2.4 Onto Central Rd 0.1 L 10.2 Edward L Grant Hwy 0.3 L 2.5 X and QL 0.4 BL 10.5 TRO Edward L. Grant Hwy 0.3 S 2.9 X Randall’s Island Connector to 0.2 Bronx L 10.8 BL into bus lane 0.0 L 3.2 E 132nd St 0.2 QL 10.8 bike lane 0.0 R 3.4 Onto Cypress then L onto side- 0.4 QR 10.8 University Ave 0.2 walk, up stairs, and X bridge R 11.0 bike path into Highbridge Park 0.1 R 3.8 and continue on bike path 0.2 QR 11.1 and continue onto High Bridge to 0.7 L 4.1 By restrooms X road into parking 0.7 Manhattan then continue south on lot and then go L onto ramp up bike path north side of bridge R 11.8 turn R past flagpole and go up 0.3 R 4.7 Onto E 127th St First Ave 0.2 ramp alongside stairs, then hard ) R onto Edgecombe heading north Uturn 4.9 U turn to L up curb cut onto Willis 0.5 Avenue Bridge path (at 125th) R 12.2 BR onto Amsterdam Ave 0.1 L 5.5 E 135th St 0.3 PIT 12.3 Highbridge Park Wa- 0.4 ter/Bathrooms -

Extreme Heat Preparations

Extreme Heat Preparations High temperatures can impact Amtrak operations as the extreme heat can cause rail, bridge and catenary wires to expand. As a safety measure, Amtrak imposes heat restrictions, which require locomotive engineers to operate trains at lower speeds than under normal operating conditions. Speed reductions are based on the rail temperature, not the ambient (air) temperature. That data ensures we’re only issuing heat restrictions when necessary. How Amtrak Measures Rail Temperature • Amtrak monitors rail temperatures and weather conditions at along its right-of-way on the Northeast Corridor between Washington and Boston; the Keystone Corridor in Pennsylvania; the Empire line in New York; the Springfield line in Connecticut and Massachusetts; and the Michigan line. By measuring the actual rail temperatures instead of the weather conditions in the area, it is possible to reduce the number of “slow orders” and their impact on operations. When Amtrak Activates Heat Restrictions The reduction of speed is based on the rail temperature, not the ambient (air) temperature. Rail temperature 131 degrees = maximum speed 100 mph Rail temperature 140 degrees = maximum speed 80 mph The exception is the Hell Gate Bridge in New York City, where ambient readings are still in use. On this section of track, when the ambient temperature reaches 105 degrees, the maximum operating speed drops to 80 mph. This is an exception because only one small area has a regular maximum operating speed of 100 mph with the rest of the line already at 80 mph or under. All commuter and freight entities operating on Amtrak infrastructure are required to adhere to Amtrak guidelines. -

Randall's Island Central Road and Hell Gate Circle

RANDALL’S ISLAND CENTRAL ROAD AND HELL GATE CIRCLE Manhattan Community Board 11 - Public Safety & Transportation Committee April 6, 2021 Background 1 2 Background • Significant increase of bicycle and pedestrian use of Randall’s Island since the start of COVID-19 • Robert F. Kennedy Bridge approach installed in 2020 Randall’s Island • Access to Hell Gate Bicycle Path expanded in 2020 3 Improvements 2 4 Improvements Northern Entrance to Hell Gate Pathway Existing: Central Road at Northern Entrance to Hell Gate Path Central Road between the Northern entrance of Hell Gate Pathway and Reilly Boulevard Improvements Central Road Central Road, K Road to Reilly Blvd • Improve intersection • Add protected bicycle lane • Add painted pedestrian island • Maintain all bus stops Northern Entrance to Existing: Central Road from K Road to Reilly Blvd Hell Gate Path Improvements Central Road Central Road from Icahn Stadium to Hell Gate Circle Add green paint to existing curbside bike lanes Existing Proposed Existing: Central Road from Icahn Stadium to Hell Gate Circle Improvements Southern Entrance to Hell Gate Pathway • Shared Lane Markings on Hell Gate Circle between the southern entrance of Hell Gate Bridge Path and Harlem River Drive • Maintain all bus stops and shelters Existing: Hell Gate Circle looking towards the southern entrance of Hell Gate Bridge Path M35 Bus Stop Southern Entrance to Hell Gate Path Summary 3 9 Summary Create Safer, Clearer Calm Traffic Connections No Changes to Existing Bus Route Existing: 7th Ave between 59 10 THANK YOU! Questions? NYC DOT NYC DOT nyc_dot NYC DOT 11. -

Queens East River & North Shore Greenway Master Plan

Queens East River & North Shore Greenway Master Plan NYC Department of City Planning • 2006 Queens East River & North Shore Greenway Master Plan Queens East River and North Shore Greenway Master Plan New York City Department of City Planning New York City Department of Parks & Recreation 2006 2006 • NYC Department of Parks & Recreation Queens East River & North Shore Greenway Master Plan Project PIN X500.97 The preparation of this report was fi nanced in part through funds from the U.S.Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration. This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The contents of this report refl ect the views of the author, who is responsible for the facts and accuracy of the data presented within. The contents do not necessarily refl ect the offi cial views or policies of the Federal Highway Administration. This report does not constitute a standard, specifi cation, or regulation. NYC Department of City Planning • 2006 Queens East River & North Shore Greenway Master Plan Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................................................1 Project Description ................................................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Study Area -

A Context for Common Historic Bridge Types

A Context For Common Historic Bridge Types NCHRP Project 25-25, Task 15 Prepared for The National Cooperative Highway Research Program Transportation Research Council National Research Council Prepared By Parsons Brinckerhoff and Engineering and Industrial Heritage October 2005 NCHRP Project 25-25, Task 15 A Context For Common Historic Bridge Types TRANSPORATION RESEARCH BOARD NAS-NRC PRIVILEGED DOCUMENT This report, not released for publication, is furnished for review to members or participants in the work of the National Cooperative Highway Research Program (NCHRP). It is to be regarded as fully privileged, and dissemination of the information included herein must be approved by the NCHRP. Prepared for The National Cooperative Highway Research Program Transportation Research Council National Research Council Prepared By Parsons Brinckerhoff and Engineering and Industrial Heritage October 2005 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF SPONSORSHIP This work was sponsored by the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials in cooperation with the Federal Highway Administration, and was conducted in the National Cooperative Highway Research Program, which is administered by the Transportation Research Board of the National Research Council. DISCLAIMER The opinions and conclusions expressed or implied in the report are those of the research team. They are not necessarily those of the Transportation Research Board, the National Research Council, the Federal Highway Administration, the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials, or the individual states participating in the National Cooperative Highway Research Program. i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The research reported herein was performed under NCHRP Project 25-25, Task 15, by Parsons Brinckerhoff and Engineering and Industrial Heritage. Margaret Slater, AICP, of Parsons Brinckerhoff (PB) was principal investigator for this project and led the preparation of the report. -

Analyzing the Potential for Commuter Train Run-Through Service at New York Penn Station August 7, 2014

Analyzing the Potential for Commuter Train Run-Through Service at New York Penn Station August 7, 2014 Prepared by Amtrak Northeast Corridor Infrastructure Investment and Development And Amtrak Operations Research Groups Abstract This paper provides a brief review of Amtrak research on the potential of through running of commuter operations in Penn Station, New York. It is intended to help inform the larger community interested in the concept as well as to assist in the planning and analysis within a number of studies of Penn Station and the Northeast Corridor that are currently underway. The paper describes through running concepts in general, and then identifies operational and infrastructure conditions specific to Penn Station which should be addressed in order to undertake a successful revenue service. Analysis discussed in this paper finds that: commuter trains would lead to fewer peak a) absent the construction of purpose-built period trains and/or less reliable operations facilities to provide wider station platforms under representative service scenarios and, b) the introduction of more robust evaluated. vertical passenger access, a through running service with high performance service Potential Through Running Territory characteristics found in other railway systems is not achievable at Penn Station. Further, current operations are optimized around the existing terminal infrastructure with its two main support yards serving in a critical role to achieving very high levels of performance. Without investment in new station facilities to compensate for the utility provided by yards, the introduction of a through running revenue service with Table of Contents Who is interested in through running and why? .............................................................................