Breedon Aggregates / Aggregate Industries Merger Inquiry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aggregate Industries

NON-CONFIDENTIAL VERSION AGGREGATE INDUSTRIES RESPONSE TO UPDATED ISSUES STATEMENT NON-CONFIDENTIAL VERSION CONTENTS SECTION PAGE 1. INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY .............................................................. 3 2. ECONOMIC OUTLOOK .................................................................................. 5 3. PROFITABILITY .............................................................................................. 6 4. MARKET DEFINITION ................................................................................... 7 5. THEORY OF HARM 1: HIGH LEVELS OF CONCENTRATION AND BARRIERS TO ENTRY MEAN THAT THE SUPPLIERS CAN EXERCISE UNILATERAL MARKET POWER ........................................... 10 6. THEORY OF HARM 2: COORDINATION BETWEEN PRODUCERS REDUCES OR PREVENTS COMPETITION ....................... 14 7. THEORY OF HARM 3: VERTICAL INTEGRATION AND EXCLUSIONARY BEHAVIOUR .................................................................. 17 8. POLICY AND REGULATION ....................................................................... 18 9. CONCLUSION ................................................................................................ 19 Error! Unknown document property name. Page 2 NON-CONFIDENTIAL VERSION 1. INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY 1.1 Aggregate Industries (AI) broadly agrees with a number of the preliminary views expressed by the Competition Commission (CC) in the Updated Issues Statement. At the hearing on 10 December the Chairman noted that the CC’s focus has “turned away from rmx” and that the -

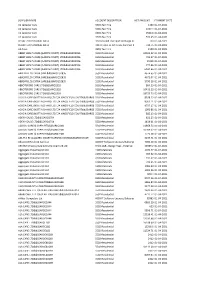

Payments to Suppliers Over £500 (ALL) April 2021

SUPPLIER NAME ACCOUNT DESCRIPTION NET AMOUNT PAYMENT DATE A1 Leicester Cars 3303-Taxi Hire 1160 01-04-2021 A1 Leicester Cars 3303-Taxi Hire 1037.4 01-04-2021 A1 Leicester Cars 3303-Taxi Hire 1504.8 01-04-2021 A1 Leicester Cars 3303-Taxi Hire 599.25 01-04-2021 REDACTED PERSONAL DATA 3201-Pooled Transport Recharge Inhouse 720 01-04-2021 REDACTED PERSONAL DATA 3113-Home to Sch Trans Contract Buses Sec 746.75 01-04-2021 AA Taxis 3303-Taxi Hire 1500 01-04-2021 ABBEY HEALTHCARE (AARON COURT) LTD&&SSARO2996 5502-Residential 34592.32 01-04-2021 ABBEY HEALTHCARE (AARON COURT) LTD&&SSARO2996 5502-Residential 703.57 01-04-2021 ABBEY HEALTHCARE (AARON COURT) LTD&&SSARO2996 5502-Residential 19218 01-04-2021 ABBEY HEALTHCARE (AARON COURT) LTD&&SSARO2996 5502-Residential 777.86 01-04-2021 ABBEY HEALTHCARE (AARON COURT) LTD&&SSARO2996 5502-Residential 6547.86 01-04-2021 ABBEYFIELDS EXTRA CARE&&SSAROE52835 5502-Residential 4674.65 01-04-2021 ABBEYFIELDS EXTRA CARE&&SSAROE52835 5502-Residential 4672.07 01-04-2021 ABBEYFIELDS EXTRA CARE&&SSAROE52835 5502-Residential 3790.28 01-04-2021 ABBOTSFORD CARE LTD&&SSARO2339 5502-Residential 864.29 01-04-2021 ABBOTSFORD CARE LTD&&SSARO2339 5502-Residential 10403.23 01-04-2021 ABBOTSFORD CARE LTD&&SSARO2339 5502-Residential 18725.73 01-04-2021 ACACIA CARE (NOTTINGHAM) LTD T/A KINGSFIELD COURT&&SSARO85405502-Residential 8528.12 01-04-2021 ACACIA CARE (NOTTINGHAM) LTD T/A KINGSFIELD COURT&&SSARO85405502-Residential 9052.71 01-04-2021 ACACIA CARE (NOTTINGHAM) LTD T/A KINGSFIELD COURT&&SSARO85405502-Residential 9707.17 -

Acquisition of Hope Construction Materials Creating the UK’S Largest Independent Building Materials Group 18 NOVEMBER 2015

Acquisition of Hope Construction Materials Creating the UK’s largest independent building materials group 18 NOVEMBER 2015 BREEDON AGGREGATES 1 ACQUISITION OF HOPE CONSTRUCTION MATERIALS FOR £336 MILLION1 Creating the UK’s largest independent vertically-integrated building materials group • Hope is a leading independent producer of cement, aggregates and concrete • £202 million cash consideration and £134 million share consideration • Acquisition on a cash- and debt-free basis Strong strategic rationale for combination • Entry into cement market through one of the UK’s largest cement plants • Extended and highly complementary geographic footprint • Stronger platform for further bolt-on acquisitions and future growth Financially compelling and value-creating transaction • Double-digit underlying earnings accretion expected in first full year post-acquisition2 • Expected annual synergies of ~£10 million from operational improvements • A transformational deal, potentially nearly doubling Breedon’s annual underlying EBITDA 1 Subject to completion adjustments 2 This should not be construed as a profit forecast and should therefore not be interpreted to mean that earnings per share in any future financial period will necessarily match or be greater than those for the relevant preceding financial period BREEDON AGGREGATES 2 BREEDON AGGREGATES IS THE UK’S LEADING INDEPENDENT AGGREGATES BUSINESS Reserves and resources A fully-integrated aggregates company Over 500m tonnes Over 1,200 employees of owned or controlled mineral reserves and resources -

Global Cement Magazine: Dearnovember Readers2013

News North America Cementos Argos Roberta report PCA Interviews Fans CO2 capture Hope plant visit Logistics www.globalcement .com May 2018 May gl bal TM Contents Subscribe Ad Index .com cement MAY 2018 MAGAZINE cement global Plant Protection Concept www. Cloud-Based Maintenance Online Condition Monitoring D-MPC Support Machine Protection Concept Logistics Logistics Solutions for predictive and proactive maintenance Condition Optimization Monitoring of Crushers Training and Mills Hope plant visit Hope plant Performance Fans Fans Load and Vibration Optimization Measurements DALOG Process Monitoring System Process Signals D-PMS PCA Interviews Increase Operating Time Avoid Stoppages Optimize Process Proactive Reduce Maintenance Cost Failure Prevention Cementos Argos Roberta Argos plant Cementos Service DALOG Torque Monitoring System Boost the Expected Life Torque D-TMS of your Equipment North America News News Independent and objective Predictive Online Condition Monitoring for Cement Plants Failure Detection DALOG Condition Monitoring System Vibration D-CMS Kiln Vertical Roller Ball Roller Mill Press Mill Meet us at: MAGAZINE MAGAZINE For more information contact: Christoph MuschaweckNASHVILLE, TN | MAY 06TH - 10TH cement Industrial Crusher Material Dust E-mail: [email protected] Transport Systems Separator Phone: +49 821 74777 - 115 global Fan LONDON, UK | MAY 23TH - 24TH Plant Protection Concept Cloud-Based Maintenance Online Condition Monitoring Support Condition Optimization Monitoring of Crushers Training and Mills Performance -

Breedon Cement Enniskillen Kendal Armagh NORTHALLERTON

SITE DIRECTORY A LEADING CONSTRUCTION MATERIALS GROUP IN THE UK AND IRELAND www.breedongroup.com NORTHERN 01382 537600 [email protected] MARYBANK BENNADROVE HEBRIDES CEANN AN ORA MOREFIELD ARDCHRONIE DRUIM REALLASGER HIGHLANDS NETHERGLEN BOYNE BAY Peterhead INVERNESS ROTHES GLEN BEAULY STIRLINGHILL Inverness DAVIOT INVERURIE DYCE TOM’S FOREST Aviemore KEMNAY Aberdeen MEADOWSIDE TULLOS CRAIGENLOW WESTHILL NORTH-EAST BANAVIE SCOTLAND EDZELL CAPO SHIERGLAS POWMYRE BENDERLOCH Dundee ETHIEBEATON FIFE & DUNDEE DUNBEG BONAWE TAYSIDE PERTH DUNDEE CEMENT TERMINAL Oban BALMULLO CLATCHARD CRAIG FURNACE Stirling ORROCK DUMBARTON DUNBAR FALKIRK GREENOCK PAISLEY PORT DUNDAS LIVINGSTON DALKEITH Edinburgh Glasgow ARDEER BLINKBONNY NORTH DRUMBOY KILMARNOCK SORN KILLOCH ARGYLL, CENTRAL BELT, SOUTH SCOTLAND TORMITCHELL & CUMBRIA BARBAE BEDLINGTON BLYTH CEMENT TERMINAL BLYTH Derry HOWDON Dumfries Carlisle SCOTSWOOD Newcastle Key SOUTH SHIELDS GATESHEAD CLAYSHANT TONGLAND Quarry BARLOCKHART Belfast LOW PLAINS DURHAM Donegal WHITECROOK NORTH-EAST Ready-mixed concrete RAISBY Asphalt ENGLAND Hartlepool NORTHERN CRIME RIGG HART Contracting Keswick LOW HARPERLEY IRELAND HARTLEPOOL Tipping BISHOP AUCKLAND MIDDLESBROUGH Concrete products STOCKTON BARTON Breedon Cement Enniskillen Kendal Armagh NORTHALLERTON Northallerton Scarborough Ingleton Dundalk Morecambe NORTH Bridlington Westport ENGLAND York Harrogate Hull Blackburn Leeds Galway Dublin Manchester REPUBLIC OF IRELAND Lincoln Chester Wrexham Derby WEST ENGLAND Nottingham Limerick AND NORTH -

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 Irish Concrete Federation B Annual Report 2018

IRISH CONCRETE FEDERATION ANNUAL REPORT 2018 Irish Concrete Federation B Annual Report 2018 INDUSTRY MISSION STATEMENT We will be a customer driven, service oriented, quality business. We will be viewed by our community and Government as an environmentally responsible industry that operates in a safe and healthy manner. We will create a work environment where our employees are highly trained and empowered to anticipate customer needs. We seek to develop successful and mutually beneficial relationships with customers, suppliers, communities and the construction industry. The concrete products industry will continue to be successful. The concrete products industry will be guided by positive leadership among the many strategies to be utilised in achieving these goals. The End Result; • Adequate Return on Investment • A Secure Future IRISH CONCRETE FEDERATION Ground Independent Irish Limestone Concrete Precast Producers Manufacturers Concrete Association Association Association of Ireland Affiliations ICF is a member of ERMCO, European Readymix Concrete Organisation and of UEPG, the European Aggregates Association. IPCA is a member of BIBM, the European Federation for Precast Concrete. EUROPEAN READY MIXED CONCRETE ORGANIZATION ERMCO ASSOCIATION EUROPEENNE DU BETON PRET A L’EMPLOI EUROPÄISCHER TRANSPORTBETONVERBAND (Union Européenne European Federation des Producteurs de for Precast Concrete Granulats) Irish Concrete Federation 1 Annual Report 2018 CONTENTS 03 04 08 11 12 JOHN MAGUIRE – FOREWORD BY CHIEF ICF COUNCIL TECHNICAL AN APPRECIATION -

AT LAST SOME ACTION? Guarantees for CASE Infrastructure GROWS Projects for INCREASED HS2 PHASE 2 AIRPORT MUST NOT CAPACITY DISTRACT PHASE 1

britpave® news AT LAST SOME ACTION? Guarantees for CASE Infrastructure GROWS projects FOR INCREASED Hs2 pHASE 2 AIRPORT MUST NOT CAPACITY DISTRACT pHASE 1 BRITPAVE ANNUAL DINNER & SEMINAR Details Inside issue 26 www.britpave.org.uk 2 welcoMe Contents Editor’s Note Page 3 transport Welcome to latest issue of Britpave News and, to those Britpave members infrastructure who I have yet to meet, hello. I am the new General Manager for Britpave appointed following the formation of a separate but linked organisation Page 4 roads Britpave Barrier Systems Ltd (BBS) on 1st June 2012. Page 6 seminar Britpave Barrier Systems Ltd has been formed to further the success of the programme Britpave Concrete Step Barrier which is becoming an increasingly common Page 7 britpave sight on motorways in the UK and throughout the EU. The company will also exhibition focus on the development of potential new markets for barrier. Page 8 airports The removal of the barrier business from its core activities will allow the Page 9 rail Britpave trade association to concentrate on developing long-term cementitious and concrete solutions for infrastructure with particular emphasis Page 10 soil stabilisation on road, rail, guided bus lanes, airports, soil stabilisation and special applications. This concentration is well-timed as there is a growing recognition Page 11 eupave of the need for increased investment in UK infrastructure. Page 12 britpave As General Manager, I will be working closely with Carol Abbey at the Britpave Members office to forward the continued development of the trade association as the focal point for the infrastructure sector and as a vehicle to help members to increase their business profile. -

Buildingworker

INSIDE: PPE • Park Adfer • Exposing exploitation Autumn 2018 The magazine for Unite construction sector members buildingWORKER Construction, Allied Trades and Technicians UniteUniteCarillion’s collapse liftinglifting – who is to blame? constructionconstruction standardsstandards Had an accident? FREE specialist legal support is just a call away With Unite you can BENEFIT from: • Recovering 100% of your If you have been personal injury compensation involved in an • Union funded legal accident at or representation for personal away from work, injury and employment cases our expert • Personal Injury claims for you solicitors are and your family here to help. Call 0800 709 007 ES/7143/12-15 www.unitetheunion.org www.unitelegalservices.org Autumn 2018 The magazine for Unite construction sector members Dear Colleagues, buildingWORKER Unite’s core reason for organising in construction is to improve standards and working conditions for members. Contents The poster at the centre of this issue sets out what 3 Gail Cartmail, assistant general those basic standards secretary, editorial should be, ensuring workers are paid fairly and work in safe conditions being the most important. Please 4 National news make every effort to pin the poster up at your workplace, so we can spread the message about what Unite strives to deliver 6 Local news for construction workers. 8 Pay and bargaining update An essential part of ensuring every workplace is safe is to make sure that you have the correct personal protective equipment 9 International news (PPE) and it fits correctly. On page 10 Unite’s national health and safety advisor Rob Miguel, details the laws on PPE and what should be worn and when. -

Sharpe Pritchard Construction Law Review 2018/2019

CONTENTS Foreword ................................................................................................................................................................... 02 Smash and Grab Adjudications .......................................................................................................................... 03 S&T (UK) Ltd v Grove Developments Ltd [2018] EWCA Civ 2448 ................................................................................................... 03 M Davenport Builders Ltd v Greer and another [2019] EWHC 318 (TCC) ....................................................................................... 03 Liquidated and Ascertained Damages (LADs) ............................................................................................... 04 Triple Point Technology Inc v PTT Public Company Ltd [2019] EWCA Civ 230 .............................................................................. 04 Collateral Warranties ............................................................................................................................................. 05 Swansea Stadium Management Company Ltd v City & County of Swansea and another [2018] EWHC 2192 (TCC) .................. 05 British Overseas Bank Nominees Ltd and Others v Stewart Milne Group Ltd [2019] CSIH 47 ....................................................... 06 New York Laser Clinic Ltd v Naturastudios Ltd [2019] EWHC 2892 (QB) ........................................................................................ 06 Practical -

Business Name D/B/A Name #1A LIFESAFER of COLORADO LLC

Business Name D/B/A Name #1A LIFESAFER OF COLORADO LLC 101 PARK AVENUE PARTNERS INC 1-800 CONTACTS INC 3 DAY BLINDS LLC 303 FURNITURE INC 303 TACTICAL LLC 303 TACTICAL 360 RAIL SERVICES LLC 3BB INC GREAT CLIPS 3D AUTOGLASS 3D STAINLESS LLC 3FORM LLC 3R Technology Solutions Inc 3SI SECURITY SYSTEMS INC 3T CULINARY INC THREE TOMATOES CATERING 4 FRONT ENGINEERED SOL INC 4283929 DELAWARE LLC ROCKY MTN PET CREMATION SERVICES 48FORTY SOLUTIONS LLC PALLET COMPANIES LLC 4imprint, Inc. 4LIFE RESEARCH CSA LLC 4LIFE RESEARCH USA LLC 50 IN 52 JOURNEY INC THE JOURNEY INSTITUTE 5071 INC 50-80 MASSAGE 5280 Contract Flooring 5280 HEATING COOLING & REFRIGERATION 5280 MAINTENANCE INC 5280 Stone Company, LLC 5280 Stone Company, LLC 5280 Telecom, LLC 5280 TOWING LLC 52Eighty Customs 5850 EAST 58TH AVENUE LLC 5850 EAST 58TH AVENUE LLC 6 ITALIAN WOLF SECURITY LLC 6171 LLC THE HIDEAWAY TAVERN 7-ELEVEN INC 7-ELEVEN STORE #38170 7-ELEVEN INC 7-ELEVEN STORE 37570 7-ELEVEN INC / JC INC 35828A 7-ELEVEN STORE 35828A 7-ELEVEN INC 23829 7-ELEVEN STORE 23829 7-ELEVEN INC 23829B 7-ELEVEN STORE 23829B 7-ELEVEN INC 34087 7-ELEVEN STORE 34087 7-ELEVEN INC 35828 7-ELEVEN STORE 35828 7-ELEVEN INC 35864 7-ELEVEN STORE 35864 7-ELEVEN INC 36013 7-ELEVEN STORE 36013 7-ELEVEN INC 36013 7-ELEVEN STORE 36013 7-ELEVEN INC 36464 7-ELEVEN STORE 36464 7-ELEVEN INC 36775 7-ELEVEN STORE 36775 7-ELEVEN INC 37291 7-ELEVEN STORE 37291 7-ELEVEN STORE 34087A 7-ELEVEN INC / S&As STORE INC 34087A 7-ELEVEN STORE 36013A EMHT INC & 7-ELEVEN INC 800-FLOWERS INC 8X8 INC A & A QUALITY APPLIANCE A & B Engineering Services LLC A CUSTOM COACH A CUT ABOVE LANDSCAPE LLC A GOOD LIL TRANNY SHOP LLC A GOOD SHOP INC A HOLE IN THE WALL CONSTRUCTIO AHW CONSTRUCTION A MAN WITH A VAN INC A SIMPLEE GORGEOUS BOUTIQUE A TO Z RENTAL CENTER, INC. -

Biggest British Private Equity Deal Sealed

marketwatch KEY DEALS Biggest British private equity deal sealed The £11.1bn takeover of Alliance advisers and joint corporate brokers. Citigroup £8bn and Heidelberg said it would be taking on I Boots represents not only the latest in a also acted as financial adviser. around £1.5bn of Hanson debt. string of megabids for FTSE 100 companies – Pessina, the Italian who was the original Heidelberg was already involved in the UK a dozen blue chip London stocks have now architect of last year’s merger between Boots market through its Castle Cement subsidiary, been taken out over the last two years – but and Alliance UniChem, said the business and the deal makes Heidelberg internationally also the single biggest private equity-financed needed to be taken off the stockmarket to the number one in aggregates, the second bid for a British company. accelerate development into new markets for a largest producer of ready-mixed concrete, and The complex bid by US private equity giant pharmacy-led healthcare and beauty group. the fourth largest producer of cement. Kohlberg Kravis Roberts in league with Steffano “The markets we serve are changing The deal follows the recent US merger Pessina, Alliance Boots’ largest shareholder dynamically,” Pessina said. between Vulcan Materials and Florida Rock and and its Deputy Chairman, was landed only after Alliance Boots was advised by Goldman other recent acquisitions in the UK market. seeing off a last-minute counter-offensive by Sachs as lead financial adviser, with Credit Cemex of Mexico, which recently acquired funds run by London private equity firm Terra Suisse and UBS acting as corporate brokers. -

Breedon Aggregates/Aggregate Industries

Breedon Aggregates and Aggregate Industries UK A report on the completed acquisition by Breedon Aggregates Limited of certain Scottish assets of Aggregate Industries UK Limited 9 April 2014 C M A 26 Crown copyright Website: www.gov.uk/cma Members of the Competition Commission who conducted this inquiry Simon Polito (Chair of the Group) Robin Aaronson Lesley Ainsworth Graham Sharp Chief Executive and Secretary of the Competition Commission David Saunders Members of the Competition and Markets Authority panel who from 1 April 2014 are responsible for the remaining stages of this inquiry Simon Polito (Chair of the Group) Robin Aaronson Lesley Ainsworth Graham Sharp Chief Executive of the Competition and Markets Authority Alex Chisholm The Competition and Markets Authority has excluded from this published version of the report information which the Inquiry Group considers should be excluded having regard to the three considerations set out in section 244 of the Enterprise Act 2002 (specified information: considerations relevant to disclosure). The omissions are indicated by []. Some numbers have been replaced by a range. These are shown in square brackets. Non-sensitive wording is also indicated in square brackets. iii The Competition Commission’s (CC’s) provisional findings were published on 7 February 2014. On 1 April 2014 the remaining functions of the CC in relation to the reference were transferred to the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), under Schedule 5 to the Enterprise and Regulatory Reform Act 2013 and the Schedule to the Enterprise and Regulatory Reform Act 2013 (Commencement No. 6, Transitional Provisions and Savings) Order 2014 (the Order). Accordingly this report is published in exercise of the CMA’s functions under sections 35 and 38 of the Enterprise Act 2002, read with paragraph 2 of the Schedule to the Order.