The Case for the Genuine Gold Dollar, by Murray N. Rothbard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Coinage Act, 1873 [United States]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6248/coinage-act-1873-united-states-176248.webp)

Coinage Act, 1873 [United States]

Volume II The Heyday of the Gold Standard, 1820-1930 1873 February 12 Coinage Act, 1873, United States: “An Act revising and amending the Laws relative to the Mints, Assay, offices, and Coinage of the United States.” With the passage of this Act, the US Congress demonetised silver and established its participation in the international gold standard. This effectively ended the official bimetallism that had existed in the United States since 1792 and demonetised silver. Initially, the consequences were limited as silver had been undervalued at the old 15:1 ratio; however, as demand for gold rose, a return to silver became increasingly attractive to those who suffered from the subsequent deflation—primarily farmers who witnessed dramatic reductions in commodity prices. Those who blamed the deflation for their financial woes came to refer to the Coinage Act as the ‘Crime of 1873’. ——— Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That the mint of the United States is hereby established as a bureau of the Treasury Department, embracing in its organization and under its control all mints for the manufacture of com, and all assay offices for the stamping of bars, which are now, or which may be hereafter, authorized by law. The chief officer of the said bureau shall be denominated the director of the mint, and shall be under the general direction of the Secretary of the Treasury. He shall be appointed by the President, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, and shall hold his office for the term of five years, unless sooner removed by the President, upon reasons to be communicated by him to the Senate. -

Unique NGC Set of Paraguay Overstrikes

TM minterrornews.com Unique NGC Set of Paraguay Overstrikes Excited About Mint Errors? 18 Page Price Guide Issue 11 • Fall 2005 Join Error World Club Inside! errorworldclub.org A Mike Byers Publication Al’s Coins Dealer in Mint Errors and Currency Errors alscoins.com pecializing in Mint Errors and Currency S Errors for 25 years. Visit my website to see a diverse group of type, modern mint and major currency errors. We also handle regular U.S. and World coins. I’m a member of CONECA and the American Numismatic Association. I deal with major Mint Error Dealers and have an excellent standing with eBay. Check out my show schedule to see which major shows I will be attending. I solicit want lists and will locate the Mint Errors of your dreams. Al’s Coins P.O. Box 147 National City, CA 91951-0147 Phone: (619) 442-3728 Fax: (619) 442-3693 e-mail: [email protected] Mint Error News Magazine Issue 11 • F a l l 2 0 0 5 Issue 11 • Fall 2005 Publisher & Editor - Table of Contents - Mike Byers Design & Layout Sam Rhazi Mike Byers’ Welcome 4 Off-Center Errors 5 Contributing Editors Off-Metal Errors 8 Tim Bullard Allan Levy Clad Layer Split Off Errors 11 Contributing Writers Double Struck 1800 $10 Eagle in Upcoming Heritage Auction 13 Heritage Galleries & Auctioneers Unique NGC Set of Paraguay Overstrikes 14 Bob McLaughlin Saul Teichman 1877 Seated Quarter Die Trial Adjustment Strike 23 Advertising AD 582-602 Byzantine Gold Justin II Full Brockage 24 The ad space is sold out. -

Modern Chinese Counterfeits of United States Coins a Collection of Observations and Tips to Help Survive the Modern Counterfeiting Epidemic

Modern Chinese Counterfeits of United States Coins A collection of observations and tips to help survive the modern counterfeiting epidemic. By: Thomas Walker I’ve had several requests for me to do a writeup on detecting modern Chinese counterfeits of Chinese coins, so here we go. In the past 2 decades, we have seen an influx of counterfeit US coins into the market to the scope of which we had never seen before. They are being mass-produced by Chinese counterfeiters in workshops dedicated to creating counterfeit coins of all types. Then these counterfeits are sold on wholesale sites (which I will not name so nefarious folks don’t go there) and can be bought for $1-2 (up to around $100 or more!) apiece from very reliable sellers. This is a low risk, high possible reward scenario for criminals and scammers. The price indicates the level of quality of the counterfeits, ranging from crappy obvious fakes (which still screw ignorant people out of hundreds of dollars) to high-quality fakes that can fool dealers and possibly even the leading third-party graders. The Chinese counterfeiters are no longer casting their counterfeits; the vast majority are die-struck on heavy-duty coin presses. In addition, the majority are not magnetic as they are being made of non-ferrous materials, such as brass. Of paramount importance to know is that the Chinese have determined that no US coin is too cheap or common to fake, so the logic that “a coin has to be real since it is not worth faking” should be thrown out the window. -

Harry Bass; Gilded Age

Th e Gilded Age Collection of United States $20 Double Eagles August 6, 2014 Rosemont, Illinois Donald E. Stephens Convention Center An Offi cial Auction of the ANA World’s Fair of Money Stack’s Bowers Galleries Upcoming Auction Schedule Coins and Currency Date Auction Consignment Deadline Continuous Stack’s Bowers Galleries Weekly Internet Auctions Continuous Closing Every Sunday August 18-20, 2014 Stack’s Bowers and Ponterio – World Coins & Paper Money Request a Catalog Hong Kong Auction of Chinese and Asian Coins & Currency Hong Kong October 7-11, 2014 Stack’s Bowers Galleries – U.S. Coins August 25, 2014 Our 79th Anniversary Sale: An Ocial Auction of the PNG New York Invitational New York, NY October 29-November 1, 2014 Stack’s Bowers Galleries –World Coins & Paper Money August 25, 2014 Ocial Auction of the Whitman Coin & Collectibles Baltimore Expo Baltimore, MD October 29-November 1, 2014 Stack’s Bowers Galleries – U.S. Coins & Currency September 8, 2014 Ocial Auction of the Whitman Coin & Collectibles Baltimore Expo Baltimore, MD January 9-10, 2015 Stack’s Bowers Galleries – World Coins & Paper Money November 1, 2014 An Ocial Auction of the NYINC New York, NY January 28-30, 2015 Stack’s Bowers Galleries – U.S. Coins November 26, 2014 Americana Sale New York, NY March 3-7, 2015 Stack’s Bowers Galleries – U.S. Coins & Currency January 26, 2015 Ocial Auction of the Whitman Coin & Collectibles Baltimore Expo Baltimore, MD April 2015 Stack’s Bowers and Ponterio – World Coins & Paper Money January 2015 Hong Kong Auction of Chinese and Asian Coins & Currency Hong Kong June 3-5, 2015 Stack’s Bowers Galleries – U.S. -

Coins, Bank Notes, Stamps & Medals

COINS, BANK NOTES, STAMPS & MEDALS Tuesday, November 7, 2017 NEW YORK COINS, BANK NOTES, STAMPS & MEDALS AUCTION Tuesday, November 7, 2017 at 2pm EXHIBITION Saturday, November 4, 10am – 5pm Sunday, November 5, Noon – 5pm Monday, November 6, 10am – 6pm LOCATION Doyle New York 175 East 87th Street New York City 212-427-2730 www.Doyle.com SHIPPING INFORMATION Shipping is the responsibility of the buyer. Upon request, our Client Services Department will provide a list of shippers who deliver to destinations within the United States and overseas. Kindly disregard the sales tax if an I.C.C. licensed shipper will ship your purchases anywhere outside the state of New York or the District of Columbia. Catalogue: $25 CONTENTS POSTAGE STAMPS 1001-1082 WORLD CURRENCY 1092-1099 UNITED STATES COINS 1162-1298 Australia 1001 China 1092-1097 Large Cent 1162 Austria 1002 Palestine/Israel 1098 3 Cents Nickel 1163, 1164 British North America 1003 Mixed Groups 1099 Seated Half Dime 1165 China 1004-1006 Nickels 1165-1169 France 1007 UNITED STATES CURRENCY 1100-1120 Seated Dime 1170 Germany 1008 Continental & Colonials 1100-1105 Barber Quarter 1171 Great Britain 1009-1011 Large & Small Size 1106-1117 Half Dollars 1172-1178 Iran 1012 Military Certificates 1118-1119 Commemorative Halves 1179-1185 Israe l 1013, 1014 Mixed Group 1099-1120 Silver Dollars 1186-1215 Japan 1015 Gold $1 1216-1218 World Wide Collections 1016-1022 WORLD COINS & TOKENS 1121-1161 Grant $1 1219 World Wide Postal History 1025-1027 Ancients 1121-1143 Gold $2 ½ 1220-1230 United States Stamps -

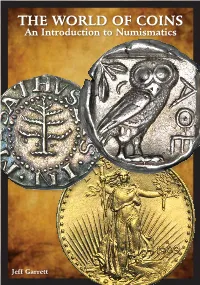

THE WORLD of COINS an Introduction to Numismatics

THE WORLD OF COINS An Introduction to Numismatics Jeff Garrett Table of Contents The World of Coins .................................................... Page 1 The Many Ways to Collect Coins .............................. Page 4 Series Collecting ........................................................ Page 6 Type Collecting .......................................................... Page 8 U.S. Proof Sets and Mint Sets .................................... Page 10 Commemorative Coins .............................................. Page 16 Colonial Coins ........................................................... Page 20 Pioneer Gold Coins .................................................... Page 22 Pattern Coins .............................................................. Page 24 Modern Coins (Including Proofs) .............................. Page 26 Silver Eagles .............................................................. Page 28 Ancient Coins ............................................................. Page 30 World Coins ............................................................... Page 32 Currency ..................................................................... Page 34 Pedigree and Provenance ........................................... Page 40 The Rewards and Risks of Collecting Coins ............. Page 44 The Importance of Authenticity and Grade ............... Page 46 National Numismatic Collection ................................ Page 50 Conclusion ................................................................. Page -

NGC Certifies Unique GOLD Belgium Franc Obverse Die Trial (1904 Design Overstruck on 1903 Design)

TM minterrornews.com NGC Certifies Unique GOLD Belgium Franc Obverse Die Trial (1904 Design Overstruck on 1903 Design) 21 Page Price Guide Inside! Issue 41 • Summer 2017 A Mike Byers Publication Now Available From Amazon.com and Zyrus Press Mint Error News Magazine Issue 41 • Summer 2017 Issue 41 • Summer 2017 Publisher & Editor - Table of Contents - Mike Byers Production Editor Sam Rhazi Contributing Editors Andy Lustig Mike Byers’ Welcome 4 Fred Weinberg NGC Certifies Unique GOLD Belgium Franc Obverse Die Trial (1904 Design Overstruck on 1903 Design) 5 Contributing Writers Heritage Auctions A Visit With Fred Weinberg 11 Jon Sullivan NGC NGC Certifies Unique Cent 15 Advertising The Baltimore Coin Show & the Coin Market 20 The ad space is sold out. Please e-mail [email protected] to be added to the waiting list. NGC Grades Rare Canadian Silver Maple Leaf Error 24 Subscriptions We are not offering a paid subscription Grading and Honesty in Numismatics 28 at this time. Issues of Mint Error News Magazine are mailed to our regular customers and coin dealers that we Prices Realized In The February 2017 Long Beach Expo Heritage Auction 31 are associated with. Issues can be downloaded for free at minterrornews.com Prices Realized In The April 2017 Dallas Heritage Auction 37 Mint Error News is the official publication of minterrornews.com. All content Copyright 2017 What Are Struck-Throughs? 40 Mint Error News. All rights reserved. No part of this magazine may be reproduced in any form without the expressed written permission of the publisher. Opinions expressed in this publication MINT ERRORS: Sales Prices for the Top 100 50 do not necessarily represent the viewpoints of Mint Error News. -

Presidential $1 Coin Act of 2005 (The “Presidential Coin Act”), 31 U.S.C

Forgotten Founders Corporation The nonprofit corporation, Forgotten Founders, was formed solely for general charitable purposes pursuant to the Florida Not for Profit Corporation Act set forth in Part I of Chapter 617 of the Florida Statutes. The specific and primary purposes for which this corporation is formed are: 1. To secure national and international U.S. Presidential recognition for the ten men who served as Constitution of 1777 U.S. Presidents under the Articles of Confederation. 2. To secure national and international founding recognition for the six men who served as Presidents of the United Colonies and States of America. 3. To secure national and international founding recognition for the U.S. Founding delegates, commissioners, judges, ministers, boards, military officers and other government officials serving the United Colonies and States of America from 1774 to 1788. 4. To operate for the advancement of U.S. Founding education, research and other related charitable purposes. 5. To establish a United States Presidential Library honoring the fourteen Presidents while aiding in the establishment of individual presidential libraries for each of the Forgotten Founder Presidents and their spouses. Thank you for taking the time to visit the Forgotten Founders Exhibit and participating in the CivicFest 2008 festivities. Forgotten Founders | Suite 308 | 2706 Alt. 19 | Palm Harbor Fl 34683 tel: 727-771-1776 | fax: 813-200-1820 | [email protected] www,ForgottenFounders.org Thank you for your interest in the U.S. Founding Half-Dollar Coin Act We at Forgotten Founders are admirers of the exemplary educational work interpreting and preserving our national history by a host of educational institutions and individuals both on and off the World Wide Web. -

459-2646 • Universalcoin.Com TABLE of CONTENTS

Est. 1994 Board Member: ICTA Member: PCGS, NGC Universal Coin & Bullion, Ltd • 7410 Phelan Blvd • Beaumont, Texas 77706 • (800) 459-2646 • UniversalCoin.com TABLE OF CONTENTS Overview Introduction to The Select 4 1 Area I Liberty Double Eagles 3 Type II $20 Double Eagles 3 Type III $20 Double Eagles 4 Carson City $20 Double Eagles 5 Area II Indian Head Gold Coins 7 $3 Indian Princess 7 $10 Indian Head Eagle 9 $2.50 Indian Head Quarter Eagle 11 $5 Indian Head Half Eagle 13 Area III Select Rare Gold Commemoratives 15 1915-S Panama-Pacific Exposition 15 Quarter Eagle 1926 Independence Sesquicentennial 16 Quarter Eagle Area IV Select American Eagles 17 Silver Eagle 17 $25 Gold Eagle 19 $25 & $50 Platinum Eagle 21 Est. 1994 Board Member: ICTA / Member: PCGS, NGC Universal Coin & Bullion President, Mike Fuljenz is an authoritative voice in the rare coin markets, especially when the topic is rare United States gold and platinum coins. In over two decades of reporting and writing on his favored topics, Mike has received twenty-four (24) Numismatic Literary Guild (NLG) Awards. Over that span, his contributions to the body of knowledge on rare coins has provided enlightenment to collectors and dealers alike. In the past year, he wrote a series of articles on the four major areas of rare United States coins that he deems his most select coin recommendations. This Special Issue of our newsletter compiles the original twelve (12) of those expanded coverage articles on the specific coins that make the elite cut within the four major areas. -

United States Gold Coin Portfolios United States Rare Gold Coins the Assembly of U.S

Parknumismatics Avenue Your Source for Rare Coins and Precious Metals P.O. Box 398239 · Miami Beach, Florida 33239 877-735-COIN (2646) United States Gold Coin Portfolios United States Rare Gold Coins The assembly of U.S. gold type sets is one of the most exciting ways to collect and invest in gold coins. This method gives the collector and investor a penetrating EIGHT SOLID REASONS WHY YOU look at numismatics and enriches his/ SHOULD OWN A VINTAGE U.S. GOLD her knowledge of history and art. They must be formed over a period of time, and COIN COLLECTION: considerable knowledge and skill must be exercised. There are countless ways 1. Vintage U.S. gold coins are very widely collected. This enormous to put together gold sets: a set of certain collector market is likely to increase appreciably in the future. Yet the supply of classic U.S. gold coins is forever fixed. design; mint sets of a certain design and denomination; or a “type set” which 2. The 12 U.S. gold coins offered in this brochure are the most contains one of each denomination of both popularly collected in America. These coins are considered Liberty and Indian designs. essential for every U.S. numismatic gold collection. They are always in demand. WHY IS IT WORTH 3. Their prices could go up at any time. The U.S. gold coin OWNING VINTAGE U.S. market is very active, and the number of collectors has increased GOLD COIN “TYPE SETS”? dramatically in the last decade, growing demand and upward price pressure. -

Rare Findings This Mailer Is Stocked Full of True One-Of-A-Kind Rarities

T H E Where Else? OIN EPOT AUGUST 2020 C 116 PoinsettD Highway • Greenville, SC 29609 • 800-922-2441 • 864-242-1679 Rare Findings This mailer is stocked full of true one-of-a-kind rarities. Examine the catalog, find the best value for you, and jump fast as many of these exclusive listings will not last long! GOLD $1,825.00 | SILVER $19.95 | PLATINUM $875.00 VIEW OUR WEBSITE AT www.thecoindepot.net Feel Free to E-mail us your want list: [email protected] FEATURED COIN SPECIALS FOR AUGUST 1884-CC 1836 REEDED EDGE 1851 CHARLOTTE $20 LIBERTY GOLD BUST HALF DOLLAR $1 GOLD DOLLAR Extra Fine Choice Almost Uncirculated Carson City gold may be the single No nicks, no dings, no marks! Just a Choice Borderline Uncirculated hottest area of the coin market. We offer wonderful, scarce 1836 Reeded Edge This scarce Charlotte gold dollar has an "entry level" coin at our lowest price half with a low mintage of 1200! Most plenty of luster and a few small marks in years. With gold approaching $2000 of these come with weakly struck re- on the cheek. an ounce, this is an amazing bargain. verses. Not this one! Grab it. $ 00 $ 00 $2,48800 3,988 2,222 1798 PLAIN 9 STANDING LIBERTY 1935-A $1 BUST DOLLAR QUARTERS HAWAII EMERGENCY NOTES Premium Quality BU Fine Choice Extremely Fine The obverse shows the beautiful Liberty These notes were stamped with the word standing holding a shield in one hand and "Hawaii" on both the obverse and re- Yes, this price is correct! Yes, this price an olive branch in the other. -

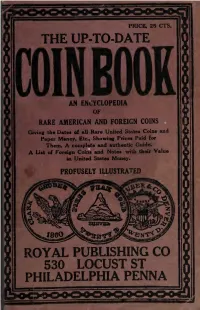

The Up-To-Date Coin Book

PRICE, 25 CTS. THE UP-TO-DATE AN ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RARE AMERICAN AND FOREIGN COINS Giving the Date* of all Rare United States Coins and Paper Money, Etc, Showing Price* Paid for Them. A complete and authentic Guide. A List of Foreign Coin* and Note* with their Value in United State* Money. PROFUSELY ILLUSTRATED ROYAL PUBLISHING CO 530 LOCUST ST PHILADELPHIA PENNA THE UP-TO-DATE COIN BOOK AN ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RARE AMERICAN AND FOREIGN COINS Giving the date of all Rare United States Coins, Paper Mo¬ ney Etc., showing prices paid for them and by Whom bought. PROFUSELY ILLUSTRATED United States and Colonial Coins, Private Gold, Fractional Currency, Confederate Coins and Notes, Encased Stamps, Etc,. List of the Standard Foreign Coins and Notes of the Prin cipal Countries of the world and their Approximate Value in U.S. money. With Useful Information Regarding Coins And Coinage. Copyrighted 1914 Royal Pub. Co. ROYAL PUBLISHING COMPANY 530 LOCUST STREET PHILADELPHIA, PENNA. PLATE “A” ,TA‘ *j* f4 * £ \ kp&-~ fetew®m b^SiSr * OUR NEW GOLD COINS Figure 1, $20. First Issue, date in Roman Letters, High Relief. Figure 2, $20. Second Issue, with and without motto. Figure 3, $10. With and without motto* Figure 4, $5, With Incused, or sunk-in lettering. UP-TO-DATE COIN BOOK 3 IMPORTANT INFORMATION ABOUT RARE COINS. PLEASE READ The invention and use of coins is attributed to the Lydians, a Greek nation, about 802 B. C., whose money was of gold and silver. The Bating of coins was iirst adapted about the fifteenth century. (For more information regarding the Ancient coins see the beautiful photographic reproductions and explanations toward the end of this book.