Drinking Water 2001D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dublin/Wicklow

Recreational facilities: a guide to recreational facilities in the East Coast Area Health Board Item Type Report Authors East Coast Area Health Board (ECAHB) Publisher East Coast Area Health Board (ECAHB) Download date 24/09/2021 15:27:28 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10147/251420 Find this and similar works at - http://www.lenus.ie/hse ,«' Recreational Facilities i lly Gap Regular physical activity can This project, funded by the confer benefits throughout Cardiovascular Health Strategy, life. It has been established Building Healthier Hearts, aims i ntaih that regular physical activity to increase awareness of area can play an important role in opportunities where physical reducing stress and improving activity can take place. • well being, reducing the risk of heart attack and stroke, and Getting started is easy. Using v assist in achieving and this resource choose an maintaining a healthy weight. activity that you enjoy and let the fun begin! So you've never really been physically active before? Or Get more active - How much? you did once, but abandoned For a health benefit we need activity efforts years ago? to be physically active for Here's the good news: No "30 minutes or more, most days matter when you start to of the week. The good news become active, making a is this activity can be commitment to physical accumulated or spread over activity can improve your 1,2, or 3 sessions. health and help you feel great! For example, 2 X 15 minute walking sessions. .*.$js 'fa ^¾¾ ' Woodland and Forest Walks Dublin/Wicklow DUBLIN and is 6km long. -

Wicklow County Council Climate Change Adaptation Strategy

WICKLOW COUNTY COUNCIL CLIMATE ADAPTATION STRATEGY June 2019 Rev 2.0 Wicklow County Council Climate Change Adaptation Strategy 1 WICKLOW COUNTY COUNCIL CLIMATE ADAPTATION STRATEGY Document Control Sheet Issue No. Date Description of Amendment Rev 1.0 Apr 2019 Draft – Brought to Council 29th April 2019 Rev 2.0 May 2019 Number of formatting changes and word changes to a number of actions: Actions Theme 1: 13, 14 and 15 and Theme 5: Actions 1 and 2 Rev 2.0 May 2019 Circulated to Statutory Consultees Public Display with SEA and AA Screening Reports from 7th June 2019 to 5th July Rev 2.0 June 2019 2019. Rev 2.0 2 WICKLOW COUNTY COUNCIL CLIMATE ADAPTATION STRATEGY ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Wicklow County Council wishes to acknowledge the guidance and input from the following: The Eastern & Midlands Climate Action Regional Office (CARO), based in Kildare County Council for their technical and administrative support and training. Neighbouring local authorities for their support in the development of this document, sharing information and collaborating on the formulation of content and actions.. Climateireland.ie website for providing information on historic weather trends, current trends and projected weather patterns. Staff of Wicklow County Council who contributed to the identification of vulnerabilities at local level here in County Wicklow and identification of actions which will enable Wicklow County Council to fully incorporate Climate Adaptation as key priority in all activities and services delivered by Wicklow County Council. Staff from all services contributed ensuring the document has reach across all relevant services. Rev 2.0 3 WICKLOW COUNTY COUNCIL CLIMATE ADAPTATION STRATEGY FOREWORD – CHIEF EXECUTIVE AND CATHOIRLEACH Ireland is at an early stage of a long and challenging process of transitioning to a low-carbon, climate resilient and environmentally sustainable economy. -

No. 4 Hazel Hill Annacurra, Aughrim, Co

ALL CORRESPONDENCE TO: Market Square House, Aughrim, Co. Wicklow. TEL: 0402 36783 WEB: www.oneillflanagan.com _____________________________________ AUCTIONEER, ESTATE AGENT, VALUER Email: [email protected] No. 4 Hazel Hill Annacurra, Aughrim, Co. Wicklow Y14 PV07 For Sale by Private Treaty This beautiful detached family home is located in a small development in the scenic village of Annacurra near Aughrim in south Co. Wicklow. The house is in show house condition throughout with many extra features. It includes private rear garden, off street parking. Viewing highly recommended and strictly By Appointment Only. Guide Price €305,000 BRANCH OFFICE: Fitzwilliam Square, Wicklow Town, Co. Wicklow A67 PX97. Tel: 0404 66410 PSRA No.: 001326 O’Neill & Flanagan Limited for themselves and for the vendor or lessors of this property whose Agents they are, give notice that:- (i) The particulars are set out as a general outline for the guidance of intending purchasers or lessees, and do not constitute, part of, an offer or contract. (ii) All descriptions, dimensions, references to condition and necessary permission for use and occupation, and other details are given in good faith and are believed to be correct, but any intending purchasers or tenants should not rely on them as statements or representations of fact but must satisfy themselves by inspection or otherwise as to the correctness of each of them. (iii) No person in the employment of O’Neill & Flanagan Limited has any authority to make or give representation or warranty whatever in relation to this property. (iv) Prices quoted are exclusive of VAT, (unless otherwise states) and all negotiations are conducted on the basis that the purchaser/lessee shall be liable for any VAT arising on the transaction. -

GAA Competition Report

Wicklow Centre of Excellence Ballinakill Rathdrum Co. Wicklow. Rathdrum Co. Wicklow. Co. Wicklow Master Fixture List 2019 A67 HW86 15-02-2019 (Fri) Division 1 Senior Football League Round 2 Baltinglass 20:00 Baltinglass V Kiltegan Referee: Kieron Kenny Hollywood 20:00 Hollywood V St Patrick's Wicklow Referee: Noel Kinsella 17-02-2019 (Sun) Division 1 Senior Football League Round 2 Blessington 11:00 Blessington V AGB Referee: Pat Dunne Rathnew 11:00 Rathnew V Tinahely Referee: John Keenan Division 1A Senior Football League Round 2 Kilmacanogue 11:00 Kilmacanogue V Bray Emmets Gaa Club Referee: Phillip Bracken Carnew 11:00 Carnew V Éire Óg Greystones Referee: Darragh Byrne Newtown GAA 11:00 Newtown V Annacurra Referee: Stephen Fagan Dunlavin 11:00 Dunlavin V Avondale Referee: Garrett Whelan 22-02-2019 (Fri) Division 3 Football League Round 1 Hollywood 20:00 Hollywood V Avoca Referee: Noel Kinsella Division 1 Senior Football League Round 3 Baltinglass 19:30 Baltinglass V Tinahely Referee: John Keenan Page: 1 of 38 22-02-2019 (Fri) Division 1A Senior Football League Round 3 Annacurra 20:00 Annacurra V Carnew Referee: Anthony Nolan 23-02-2019 (Sat) Division 3 Football League Round 1 Knockananna 15:00 Knockananna V Tinahely Referee: Chris Canavan St. Mary's GAA Club 15:00 Enniskerry V Shillelagh / Coolboy Referee: Eddie Leonard 15:00 Lacken-Kilbride V Blessington Referee: Liam Cullen Aughrim GAA Club 15:00 Aughrim V Éire Óg Greystones Referee: Brendan Furlong Wicklow Town 16:15 St Patrick's Wicklow V Ashford Referee: Eugene O Brien Division -

Baptisms, Marriages & Burials 1777 – 1819

THE PARISH REGISTERS OF CHRIST CHURCH, DELGANY VOLUME 2 BAPTISMS 1777-1819 MARRIAGES 1777-1819 BURIALS 1777-1819 TRANSCRIBED AND INDEXED Diocese of Glendalough County of Wicklow The Anglican Record Project The Anglican Record Project - the transcription and indexing of Registers and other documents/sources of genealogical interest of Anglican Parishes in the British Isles. Twenty-second in the Register Series. CHURCH (County, Diocese ) BAPTISMS MARRIAGES BURIALS Longcross, Christ Church 1847-1990 1847-1990 1847-1990 (Surrey, Guildford ) [Aug 91] Kilgarvan, St Peter's Church 1811-1850 1812-1947 1819-1850 (Kerry, Ardfert & Aghadoe )[Mar 92] 1878-1960 Fermoy Garrison Church 1920-1922 (Cork, Cloyne ) [Jul 93] Barragh, St Paul's Church 1799-1805 1799-1805 1799-1805 (Carlow, Ferns ) [Apr 94] 1831-1879 1830-1844 1838-1878 Newtownbarry, St Mary's Church 1799-1903 1799-1903 1799-1903 (Wexford, Ferns ) [Oct 97] Affpuddle, St Laurence's Church 1728-1850 1731-1850 1722-1850 (Dorset, Salisbury ) [Nov 97] Barragh, St Paul's Church 1845-1903 (Carlow, Ferns ) [Jul 95] Kenmare, St Patrick's Church 1819-1950 (Kerry, Ardfert & Aghadoe )[Sep 95] Clonegal, St Fiaac's Church 1792-1831 1792-1831 1792-1831 (Carlow/Wexford/Wicklow, Ferns ) [May 96] Clonegal, St Fiaac's Church 1831-1903 (Carlow/Wexford/Wicklow, Ferns ) [Jul 96] Kilsaran, St Mary’s Church 1818-1840 1818-1844 1818-1900 (Louth, Armagh ) [Sep 96] Clonegal, St Fiaac's Church 1831-1906 (Carlow/Wexford/Wicklow, Ferns ) [Feb 97] (Continued on inside back cover.) JUBILATE DEO (Psalm 100) O be joyful in the Lord, all ye lands: serve the Lord with gladness, and come before his presence with a song. -

Marref-2015-Wicklow-Tally.Pdf

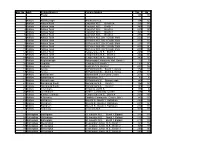

Box No LEA Polling District Polling Station Yes No Postal 188 137 1 Arklow Annacurragh Annacurra N.S. 134 127 2 Arklow Arklow Rock Carysfort N.S., Booth 5A 245 180 3 Arklow Arklow Town Carysfort N.S., Booth 1 345 102 4 Arklow Arklow Town Carysfort N.S., Booth 2 287 195 5 Arklow Arklow Town Carysfort N.S., Booth 3 363 113 6 Arklow Arklow Town Carysfort N.S., Booth 4 281 170 7 Arklow Arklow Town St Peters N.S. Bth 1 Castle Park 259 144 8 Arklow Arklow Town St Peters N.S. Bth 2 Castle Park 200 157 9 Arklow Arklow Town St Peters N.S. Bth 3 Castle Park 223 178 10 Arklow Arklow Town St Peters N.S. Bth 4 Castle Park 204 151 11 Arklow Arklow Town St Peters N.S. Bth 5 Castle Park 207 182 12 Arklow Arklow Town Templerainey N.S., Booth 1 247 135 13 Arklow Arklow Town Templerainey N.S., Booth 2 242 107 14 Arklow Arklow Town Templerainey N.S., Booth 3 240 115 15 Arklow Aughavanagh Askanagap Community Hall, Booth 1 42 54 16 Arklow Aughrim Aughrim N.S.,Booth 1 230 141 17 Arklow Aughrim Aughrim N.S.,Booth 2 221 146 18 Arklow Avoca St Patricks N.S., Booth 1, Avoca 172 110 19 Arklow Avoca St Patricks N.S., Booth 2, Avoca 236 111 20 Arklow Ballinaclash Ballinaclash Community Centre 255 128 21 Arklow Ballycoogue Ballycoogue N.S. 97 83 22 Arklow Barnacleagh St Patricks N.S., Barnacleagh 149 111 23 Arklow Barndarrig South Barndarrig N.S. -

Sea Statement Wicklow County Development Plan

SEA STATEMENT FOR THE WICKLOW COUNTY DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2016-2022 for: Wicklow County Council County Buildings Station Road Wicklow Town County Wicklow by: CAAS Ltd. 2nd Floor, The Courtyard 25 Great Strand Street Dublin 1 NOVEMBER 2016 Includes Ordnance Survey Ireland data reproduced under OSi licence no. 2009/10 CCMA/Wicklow County Council. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Ordnance Survey Ireland and Government of Ireland copyright © Ordnance Survey Ireland 2008 SEA Statement for the Wicklow County Development Plan 2016-2022 Table of Contents Section 1 Introduction ............................................................................................ 1 1.1 Terms of Reference ..........................................................................................................1 1.2 SEA Definition .................................................................................................................. 1 1.3 Legislative Context ............................................................................................................1 1.4 Content of the SEA Statement ........................................................................................... 1 1.5 Implications of SEA for the Plan .........................................................................................1 Section 2 How Environmental Considerations were integrated into the Plan........ 3 2.1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 3 2.2 Consultations -

Under 7 & 9 Hurling & Football Fixtures Give Respect, Get Respect

The Garden County Go Games Little Buds Programme A Place where all Children Bloom Under 7 & 9 Hurling & Football Fixtures Give Respect, Get Respect Recommendations for Age Groups 2017 Under 7 Under 9 Players born in 2010 & 2011 Players born in 2008 & 2009 Football Friday Night Clubs/18 Clubs Saturday Morning Clubs/18 Clubs Avoca Kilbride/Lacken AGB Blessington Barndarrig Valleymount St Patricks Hollywood Rathnew Dunlavin Ashford Donard/Glen Avondale Stratford/Grangecon Laragh Baltinglass Ballinacor Kiltegan An Tochar Knockananna Kilmacanogue Ballymanus Enniskerry Tinahely Bray Emmets Shillelagh Fergal Ogs Coolkenno Eire Og Greystones Carnew Kilcoole Coolboy Newtown Annacurra Newcastle Aughrim Hurling Friday Night Clubs / 16 Clubs Barndarrig Kilmacanogue Kiltegan St Patricks Kilcoole Tinahely Avondale Bray Emmets Kilcoole Carnew Fergal Ogs Glenealy Aughrim Eire Og Greystones ARP Stratford/Grangecon/Hollywood/Dunlavin The Full “Garden County Go Games Little Buds Programme” for 2017 will be sponsored by the Wicklow People Wicklow People are going to give us a lot of coverage but we need photos taken with the advertising board that will be supplied to each club. Club Go Games PR person to be appointed to send in photos for Twitter, Facebook and Wicklow People To the following Email Address shall be used immediately after each home blitz when returning photographs. We need all clubs corporation on this to ensure we have a good quality section in the Wicklow People each week. The onus is on the Home club to take the photographs of all teams -

File Number Wicklow County Council

DATE : 30/04/2019 WICKLOW COUNTY COUNCIL TIME : 16:04:55 PAGE : 1 P L A N N I N G A P P L I C A T I O N S PLANNING APPLICATIONS RECEIVED FROM 22/04/19 TO 26/04/19 under section 34 of the Act the applications for permission may be granted permission, subject to or without conditions, or refused; The use of the personal details of planning applicants, including for marketing purposes, maybe unlawful under the Data Protection Acts 1988 - 2003 and may result in action by the Data Protection Commissioner, against the sender, including prosecution FILE APP. DATE DEVELOPMENT DESCRIPTION AND LOCATION EIS PROT. IPC WASTE NUMBER APPLICANTS NAME TYPE RECEIVED RECD. STRU LIC. LIC. 19/428 William Hender Phillips P 23/04/2019 detached two storey dwelling which will include four bedrooms, associated reception rooms, landscaping and site works. The house will be approximately 218 sqm. A new site entrance will be constructed which will give access to the existing laneway which leads onto the R764 road Ballycurry Ashford Co. Wicklow 19/429 Zoe & Sean Larkin P 23/04/2019 dormer type extension to existing bungalow and erect an extension to the side which will consist of the following (a) renovation and extension of the ground floor to create additional living space including the rearrangement of internal layouts with associated demolition works (b) removal of the existing roof and replace it with a dormer roof space to accommodate bedrooms (c) renovate and extend the existing storage shed and workshop (d) all with ancillary works Boglands Arklow Co. -

Weekly Lists

Date: 03/06/2021 WICKLOW COUNTY COUNCIL TIME: 11:37:23 AM PAGE : 1 P L A N N I N G A P P L I C A T I O N S PLANNING APPLICATIONS RECEIVED FROM 24/05/2021 To 28/05/2021 under section 34 of the Act the applications for permission may be granted permission, subject to or without conditions, or refused; The use of the personal details of planning applicants, including for marketing purposes, maybe unlawful under the Data Protection Acts 1988 - 2003 and may result in action by the Data Protection Commissioner, against the sender, including prosecution FILE APPLICANTS NAME APP. DATE DEVELOPMENT DESCRIPTION AND EIS PROT. IPC WASTE NUMBER TYPE RECEIVED LOCATION RECD. STRU LIC. LIC. 21/601 Kathleen Keogh P 24/05/2021 side extension to existing bungalow, new N N N domestic garage and ancillary works Crosskeys Dunlavin Co. Wicklow 21/602 Conor Carroll P 24/05/2021 the construction of a single storey dwelling, new N N N site entrance, wastewater treatment system to current EPA standards, private well and all ancillary site works Ardoyne Tullow Co. Carlow 21/603 L & S Nicol P 24/05/2021 the construction of an agricultural building N N N (44m2) for use as a learning space, ancillary to the existing agricultural programmes provided on site, together with planning permission for the upgrade of existing effluent treatment system, all together with associated site works Windrush Farm Carrignamuck Upper Newtownmountkennedy Co. Wicklow Date: 03/06/2021 WICKLOW COUNTY COUNCIL TIME: 11:37:23 AM PAGE : 2 P L A N N I N G A P P L I C A T I O N S PLANNING APPLICATIONS RECEIVED FROM 24/05/2021 To 28/05/2021 under section 34 of the Act the applications for permission may be granted permission, subject to or without conditions, or refused; The use of the personal details of planning applicants, including for marketing purposes, maybe unlawful under the Data Protection Acts 1988 - 2003 and may result in action by the Data Protection Commissioner, against the sender, including prosecution FILE APPLICANTS NAME APP. -

Appendix a Interim Midlands and GDA Water Resource Plan

Water Supply Project Eastern and Midlands Region Appendix A Interim Midlands and GDA Water Resource Plan Interim Midlands and GDA Water Resource Plan Version 0.2 Date: October 2016 161027WSP1_FOAR Appendix A Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................. 1 WATER SERVICES STRATEGIC PLAN ................................................................................................................. 2 IRISH WATER’S APPROACH ............................................................................................................................ 3 RISK OVERVIEW........................................................................................................................................... 4 PRODUCTION RISK ................................................................................................................................... 4 ABSTRACTION LICENCING .......................................................................................................................... 5 GROWTH ............................................................................................................................................... 7 CSO CENSUS DATA .............................................................................................................................. 8 INDUSTRIAL GROWTH ........................................................................................................................... 9 OBSERVED -

By Email to [email protected] RC3 Team Water Division Commission For

By email to [email protected] RC3 Team Water Division Commission for Regulation of Utilities The Exchange Belgard Square North Tallaght Dublin 24 11th September 2019 Re: Consultation on Irish Water Revenue Control 3 (2020 – 2024) Dear Sir/Madam, The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has reviewed the CRU’s consultation paper on Irish Water Revenue Control 3 (2020 – 2024) and welcomes the opportunity to comment. We wish to thank the CRU for the meeting held on 25th June 2019 which provided the opportunity to improve our understanding of the five-year Capital Investment Plan for the Revenue Control 3 (RC3) period, and to discuss our respective objectives as environmental and economic regulators of Irish Water. We wish to provide the following comments on the consultation paper: 1. Spend Profile Irish Water’s spend profile in Table 14 of the consultation paper shows a significant increase during the final two years of the five-year revenue control period, most notably on future proofing of water and waste water services and supplies (€361m in 2022, €536m in 2023 and €646m in 2024). Such an increase in expenditure and related activity over a very short period will require a very substantial development of capacity and a critical focus on addressing delays in procurement and approvals processes, including planning and site acquisition in 2020 and 2021. The EPA suggests that metrics relating to these steps in the delivery process are developed and included in the RC3 framework. 2. Irish Water’s Performance against IRC2 Targets The EPA notes that Irish Water has not delivered all of the expected outcomes set out in their investment targets in IRC2 and as a result, a significant number of projects will spill over into the RC3 investment period.