Layne14cv14.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Raynaud's Phenomenon and Erythromelalgia

Temperature-associated vascular disorders: Raynaud’s phenomenon and erythromelalgia. INTRODUCTION We are too much accustomed to attribute to a single cause that which is the product of several, and the majority of our controversies come from that. Baron Justus von Leibig (1803-73) Superficially, Raynaud's phenomenon, a disease associated with cold, and erythromelalgia, a warmth related disorder, could be considered the antithesis of each other. However, both these microcirculatory disorders, first described in the second half of the nineteenth century, have many features in common and, indeed, may share the same etiology, that is microvascular ischemia. The complicated structure that is the microcirculation can produce a variety of responses to a single noxious stimulus with sensations of cold and heat at opposite ends of the spectrum. In this chapter Raynaud's phenomenon and erythromelalgia -are compared and contrasted so that the correct diagnosis of 'these conditions and appropriate remedy can be selected by the clinician. Raynaud's Phenomenon Maurice Raynaud first defined the syndrome which bears his name 133 years ago.1 He described episodic digital ischemia provoked by cold and emotion. It is classically manifest by pallor of the affected part followed by cyanosis and rubor. Vasospasm in the digital vessels leads to the pallor (Fig. 22.1). The subsequent static venous blood leads to the development of cyanosis. The rubor is caused by hyperemia after the return of blood flow. Raynaud's phenomenon (RP) can be a benign condition but, if severe, can cause digital ulceration and gangrene. It is nine times more common in women than in men and has an overall prevalence in the population of approximately 10%, although it may affect as many as 20-30% of women in the younger age groups.2 There is also a familial predisposition which is more marked if the age of onset is less than 30 years.3 Until recently little was known about the true etiology and the extent of the disorder. -

Arterial Manifestations in Young People

Arterial Manifestations in Young People Ann Marie Kupinski, PhD RVT RDMS FSVU North Country Vascular Diagnostics, Inc, & Albany Medical College, Albany, NY Objectives Describe arterial pathology encountered in young people Discuss criteria used to diagnose nonatherosclerotic disease entities Present cases which illustrate ultrasound findings of arterial disease in young people Arterial Disease in Young People • Approx. 90% of PAD and extracranial arterial disease is due to atherosclerosis • Nonatherosclerotic diseases can include: • Inflammatory diseases • Non-inflammatory diseases (FMD) • Congenital abnormalities • Acquired diseases • Injuries Testing Options • Ultrasound – Useful with large vessel disease – Giant Cell, Takayasu’s, Radiation arteritis – Injury/Trauma • Physiologic testing (PVR, PPG, pressures) – Useful with small vessel disease Buerger’s Disease (Thromboangiitis obliterans) Vasospastic Disease Fibromuscular dysplasia FMD Noninflammatory Nonatherosclerotic Young individuals (mean onset 48 yrs) Women (3:1) Affects small to medium- sized arteries Intima, media or adventitia FMD Distribution Renal 60-75% Cerebrovascular 25-30% Visceral 9% Extremity Arteries 5% Has also been observed in coronary arteries, pulmonary arteries and the aorta 28% of patients have at least two vascular beds involved Intimal fibroplasia Smooth focal stenosis with a concentric band Long smooth tubular stenosis Poloskey, et al. Circulation 2012;125 Medial fibroplasia Alternating areas of thinned media and thickened fibromuscular -

ESVM Guidelines – the Diagnosis and Management of Raynaud's Phenomenon

413 Review ESVM guidelines – the diagnosis and management of Raynaud’s phenomenon Writing group Jill Belch1, Anita Carlizza2, Patrick H. Carpentier3, Joel Constans4, Faisel Khan1, and Jean-Claude Wautrecht5 1 University of Dundee School of Medicine, Dundee, United Kingdom 2 Azienda Ospedaliera S.Giovanni-Addolorata, Rome, Italy 3 Grenoble University Hospital, Grenoble, France 4 Hopital St Andre, Bordeaux, France 5 Cliniques universitaires de Bruxelles, Brussels, Belgium ESVM board authors Adriana Visona6, Christian Heiss7, Marianne Brodeman8, Zsolt Pécsvárady9, Karel Roztocil10, Mary-Paula Colgan11, Dragan Vasic12, Anders Gottsäter13, Beatrice Amann-Vesti14, Ali Chraim15, Pavel Poredoš16, Dan-Mircea Olinic17, Juraj Madaric18, and Sigrid Nikol19 6 Angiology Unit, Azienda ULSS 2, Marca Trevigiana, Treviso, Italy 7 Department of Cardiology, Pulmonology and Vascular Medicine, Düsseldorf, Germany 8 Division of Angiology, Medical University, Graz, Austria 9 Head of 2nd Dept. of Internal Medicine, Vascular Center, Flor Ferenc Teaching Hospital, Kistarcsa, Hungary 10 Institute of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, Prague, Czech Republic 11 St. James’s Hospital and Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland 12 Clinical Centre of Serbia, Belgrade, Serbia 13 Department of Vascular Diseases, Skåne University Hospital, Sweden 14 Clinic for Angiology, University Hospital Zurich, Switzerland 15 Department of Vascular Surgery, Cedrus Vein and Vascular Clinic, Lviv Hospital, Lviv, Ukraine 16 University Medical Centre Ljubljana, Slovenia 17 Medical Clinic no. 1, -

Rheumatic Disorders As Paraneoplastic Syndromes ☆ ⁎ Vito Racanelli, Marcella Prete, Carla Minoia, Elvira Favoino, Federico Perosa

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Autoimmunity Reviews 7 (2008) 352–358 www.elsevier.com/locate/autrev Rheumatic disorders as paraneoplastic syndromes ☆ ⁎ Vito Racanelli, Marcella Prete, Carla Minoia, Elvira Favoino, Federico Perosa Department of Internal Medicine and Clinical Oncology, University of Bari Medical School, Bari, Italy Received 22 January 2008; accepted 6 February 2008 Available online 22 February 2008 Abstract The long-established observation that some rheumatologic disorders (RDs) are associated with – or precede – the clinical manifestations of a variety of solid and hematological tumors represents an important clue for the early diagnosis and effective treatment of the cancers. Inflammatory myopathies, seronegative rheumatoid arthritis and some atypical vasculitides are the most frequently reported paraneoplastic RDs, although paraneoplastic scleroderma- and lupus-like syndromes, erythema nodosum, and Raynaud's syndrome have also been observed. Generally, the clinical course of a paraneoplastic RD parallels that of the cancer, and surgical removal of the tumor or its medical treatment usually results in a marked regression of the clinical manifestations of the RD. Most paraneoplastic RDs are difficultly distinguishable from idiopathic RDs. Even so, some atypical features of the clinical presentation raise the suspicion of an underlying tumor. This review summarizes current hypotheses for the pathogenesis that leads a tumor to present as an RD and discusses the clinical features that help distinguish paraneoplastic -

Early-Onset Osteoarthritis, Charcot-Marie-Tooth Like Neuropathy, Autoimmune Features, Multiple Arterial Aneurysms and Dissection

Early-Onset Osteoarthritis, Charcot-Marie-Tooth Like Neuropathy, Autoimmune Features, Multiple Arterial Aneurysms and Dissections: An Unrecognized and Life Threatening Condition Me´lodie Aubart1, Delphine Gobert2, Fleur Aubart-Cohen3, Delphine Detaint1,4,5, Nadine Hanna6, Hyacintha d’Indya6, Janine-Sophie Lequintrec4, Philippe Renard4, Anne-Marie Vigneron4, Philippe Dieude´ 7,8, Jean-Pierre Laissy8,9, Pierre Koch9, Christine Muti4, Joelle Roume4, Veronica Cusin4, Bernard Grandchamp8, Laurent Gouya4,10, Eric LeGuern11, Thomas Papo2,8, Catherine Boileau6,10, Guillaume Jondeau1,4,8* 1 INSERM U698, Hoˆpital Bichat, Paris, France, 2 AP-HP, Hoˆpital Bichat, Service de Me´decine Interne, Hoˆpital Bichat, Paris, France, 3 AP-HP, Service de Me´decine Interne, Hoˆpital Pitie´-Salpe´trie`re, Paris, France, 4 AP-HP, Hoˆpital Bichat, Centre de re´fe´rence pour les syndromes de Marfan et apparente´s, Service de Cardiologie, Paris, France, 5 AP-HP, Hoˆpital Bichat, Service de Cardiologie, Paris, France, 6 AP-HP Ge´ne´tique mole´culaire, Boulogne, France, 7 AP-HP, Hoˆpital Bichat, Service de Rhumatologie, Hoˆpital Bichat, Paris, France, 8 Universite´ Denis Diderot, Paris 7, UFR de Me´decine, Paris, France, 9 AP-HP, Hoˆpital Bichat, Service de Radiologie, Paris, France, 10 Universite´ Versailles SQY, UFR des Sciences de la Sante´, Guyancourt, France, 11 AP-HP, De´partement de Ge´ne´tique, Hoˆpital Pitie´-Salpe´trie`re, Paris, France Abstract Background: Severe osteoarthritis and thoracic aortic aneurysms have recently been associated with mutations in the SMAD3 gene, but the full clinical spectrum is incompletely defined. Methods: All SMAD3 gene mutation carriers coming to our centre and their families were investigated prospectively with a structured panel including standardized clinical workup, blood tests, total body computed tomography, joint X-rays. -

Clinical Rationale

REVATIO (sildenafil) RATIONALE FOR INCLUSION IN PA PROGRAM Background Pulmonary arterial hypertension is a rare disorder of the pulmonary arteries in which the pulmonary arterial pressure rises above normal levels in the absence of left ventricular failure. This condition can progress to cause right-sided heart failure and death (1-2). Revatio received approval on May 26, 2009 for treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) which is classified by WHO as Group 1 (1). Revatio is used to treat pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH, high blood pressure in the lungs) to improve the exercise ability (1). Sildenafil, at different dosages, is also marketed as Viagra for the treatment of erectile dysfunction which is a plan exclusion (1). The World Health Organization (WHO) has classified pulmonary hypertension into five different groups: (2) WHO Group 1: Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension ( PAH) 1.1 Idiopathic (IPAH) 1.2 Heritable PAH 1.2.1 Germline mutations in the bone morphogenetic protein receptor type 2 (BMPR2) 1.2.2 Activin receptor-like kinase type 1 (ALK1), endoglin (with or without hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia), Smad 9, caveolin-1 (CAV1), potassium channel super family K member-3 (KCNK3) 1.2.3 Unknown 1.3 Drug-and toxin-induced 1.4 Associated with: 1.4.1 Connective tissue diseases 1.4.2 HIV infection 1.4.3 Portal hypertension 1.4.4 Congenital heart diseases (e.g. pulmonary artresia) 1.4.5 Schistosomiasis 1'. Pulmonary vena-occlusive disease (PVOD) and/or pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis (PCH) 1". Persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN) Ravatio FEP Clinical Rationale REVATIO (sildenafil) The diagnosis of WHO Group 1 PAH requires a right heart catheterization to demonstrate an mPAP ≥ 20mmHg at rest and a pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) ≥ 3 Wood units, mean pulmonary capillary wedge pressure ≤ 15mmHg (to exclude pulmonary hypertension due to left heart disease, i.e. -

Cardiovascular Involvement in Systemic Sclerosis: a Case of Atrial Septal Aneurysm Associated with Intracranial Aneurysm M

40 M. Oberson, S. Chevili Applied Cardiopulmonary Pathophysiology 14: 40-42, 2010 Cardiovascular involvement in systemic sclerosis: A case of atrial septal aneurysm associated with intracranial aneurysm M. Oberson1, S. Chevili2 1Department of Cardiology, University Hospital of Bern, Bern, Switzerland; 2Department of Internal Medicine, Ospedale Italiano, Lugano, Switzerland Introduction the sequelae of pulmonary hypertension (5) which is secondary to damage in the lung. There is increasing concern about vascular There has been an increased awareness and cardiac involvement in systemic sclerosis of left ventricular abnormalities in SSc pa- (SSc). This is a systemic infiltrative disorder tients, but the occurrence of cardiac that commonly affects the cardiovascular sys- aneurysms seems to be a rare complication tem and this case is presented to draw atten- of SSc, only few cases are illustrated in the lit- tion to the possibility of a pathophysiological erature (6). connection between SSc and cardiovascular Vascular abnormalities such as fingertip aneurysm formation. No data exist on the in- ulcers and Raynaud’s syndrome as well as in- cidence or natural history of aneurysm in pa- volvement of other organs including kidney tients with SSc and to the best of our knowl- and the gastrointestinal tract, are prominent edge, there is no other report to date of atri- features of the disease. Macrovascular in- al septal aneurysm associated with intracra- volvement in SSc has received relatively little nial aneurysm in SSc. attention, the prevalence of peripheral large The heart is one of the major organs in- vessel disease is increased in SSc, on the oth- volved in SSc (1,2), the involvement of which er hand, the association with vascular can be manifested by myocardial disease, aneurysm is poorly understood, few reports conduction system abnormalities and arrhyth- are sporadically described (7-9). -

Differentiation of Primary and Secondary Raynaud's Disease by Carotid Arterial Stiffness

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 25, 336±341 (2003) doi:10.1053/ejvs.2002.1845, available online at http://www.sciencedirect.com on Differentiation of Primary and Secondary Raynaud's Disease by Carotid Arterial Stiffness K.-S. Cheng1, A. Tiwari1, A. Boutin1, C. P. Denton2, C. M. Black2, R. Morris3, A. M. SeifalianÃ1 and G. Hamilton1 1Cardiovascular Haemodynamic Unit, University Department of Surgery, 2University Department of Rheumatology and 3University Department of Primary Care and Population Sciences, Royal Free and University College Medical School, University College London and The Royal Free Hospital, London NW3 2QG, U.K. Introduction: primary Raynaud's disease may be difficult to differentiate clinically from the secondary form with an underlying connective tissue, haematological, neurovascular or drug-induced disorder. We undertook a study to determine the elastic carotid and muscular femoral arterial biomechanical properties and intima-media thickness (IMT) in subjects with primary and secondary Raynaud's disease, to assess whether these parameters could differentiate the two conditions. Methods: twenty patients with primary Raynaud's disease and 53 subjects with secondary Raynaud's associated with scleroderma (systemic sclerosis, SSc) had measurements of their carotid and femoral wall mechanics with a duplex scanner coupled to a Wall Track system. Their age, gender, body mass index, heart rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressures, presumed cardiovascular load, plasma creatinine, fasting cholesterol, triglyceride and glucose concentrations were also measured. Results: the carotid elastic properties [mean (SD): elastic modulus: 560 (180) vs 1204 (558) mmHg, p 5 0.001 and stiffness index: 5.69 (1.35) vs 11.92 (6.4), p 5 0.001 for primary and secondary Raynaud's respectively] were significantly impaired in patients with secondary Raynaud's disease even after adjustment for potentially influencing physiological and biochemical variables. -

Migraine and Cardiovascular Disease

Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain © 2014 American Headache Society Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. doi: 10.1111/head.12410 Headache Toolbox Migraine and Cardiovascular Disease The presence or absence of cardiovascular disease caused headaches. One very interesting study found that can influence the risks associated with migraine, as well if patients knew they had high blood pressure, 74% also as the choice of optimal treatment. Migraine itself is said they had headache. If the patient did not know they considered a primary headache disorder, that is, it is not had high blood pressure, only 16% said they had caused by an underlying disease. However, much time headache. Large studies have backed this up, that if a has been spent studying diseases that appear to occur patient does not know they have hypertension, no more frequently in migraineurs. If these diseases are seen increase was found in headache frequency. Other studies more frequently in those who have migraine compared have estimated a risk of hypertension to be twice as high with the general population, they are called comorbid in migraineurs. disorders. Another source of investigation is whether, if A study of 21,537 individuals published in the these comorbid disorders are effectively managed, the medical journal Cephalalgia in 2006 showed that migraines will improve or become more treatable. elevations in diastolic blood pressure (the lower number), It is common to think of migraines as being related not systolic blood pressure (the top number), were to blood vessels or vascular in origin, despite evidence to correlated with migraine. -

The Digital Circulation in Peripheral Vascular Diseases

THE DIGITAL CIRCULATION IN PERIPHERAL VASCULAR DISEASES Milton Mendlowitz J Clin Invest. 1942;21(5):547-549. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI101332. Research Article Find the latest version: https://jci.me/101332/pdf THE DIGITAL CIRCULATION IN PERIPHERAL VASCULAR DISEASES By MILTON MENDLOWITZ (From the Medical Services of The Mount Sinai Hospital, New York) (Received for publication April 2, 1942) In a previous communication (1), methods extreme decrease in digital blood flow to approxi- were described for studying the digital blood flow, mately four per cent of the normal, with a corre- blood pressure, and vascular resistance in normal spondingly extreme increase in digital vascular subjects and in patients with hypertension and resistance to the height of 1740 units (normal coronary thrombosis. These methods have been 63 to 96 units). The digital arterial blood pre- applied to the investigation of Raynaud's syn- sure was somewhat low and the brachial-digital drome, scleroderma, and thrombo-angiitis ob- arterial pressure gradient moderately increased. literans involving the upper extremities. Seven cases of scleroderma were studied. In one case (C. R.) only the neck, chest, face, and RESULTS legs were involved, there being no perceptible The results are presented in Table I. In three sclerodactyly. In this case, the digital blood flow cases of typical Raynaud's disease, one of less than was at the lower limit and the digital vascular one year's duration, and the others of less than resistance at the upper limit of normal. In the TABLE I Peripheral vascular diseases After body warming Brachial Digital Digital Digital Patient Age and sex Diagnosis Duration blood blood blood vascular pressure pressure flow resistance cc. -

The Raynaud Syndrome MARTIN BIRNSTINGL

Postgraduate Medical Journal (May 1971) 47, 297-310. Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.47.547.297 on 1 May 1971. Downloaded from The Raynaud syndrome MARTIN BIRNSTINGL M.S., F.R.C.S. St Bartholomew's Hospital, London, E.C.1 'Arteritis. Thank heaven I have not to express in a later paper (1874) he put forward 'the hypothesis any opinion either upon its frequency, or upon the of a contraction of the terminal vascular ramifica- share which belongs to it in the different arterial tions, varying from a simple diminution of calibre changes, or to the part which it plays in general.' up to complete narrowing of the lumen of the vessel. Maurice Raynaud, 1862. To the total closure of the arterial and venous vessels would correspond an exsanguine and Maurice Raynaud described in his thesis 'De cadaveric state of the extremities ... whilst the l'Aphyxie Locale et de la Gangrene Symetrique des arterioles only being closed and the venules open, Extremites' (1862) examples of both episodic digital one would see a venous stasis produced by failure asphyxia and frank local gangrene, which justifies of vis a tergo, whence the cyanosis and livid ap. the broad pathological field covered by the present pearance'. article. Unfortunately he failed to understand the widely Protected by copyright. varying pathology of the examples he described, or Definitions that necrosis or frank gangrene can only result from Raynaud's syndrome. The general syndrome of actual structural obliteration of the vessels and it arterial insufficiency of the fingers, regardless of was left to Jonathan Hutchison (1901) to point out cause, and whether presenting as episodic or con- the many different diseases which are liable to pre- tinuous ischaemia, digital necrosis or gangrene. -

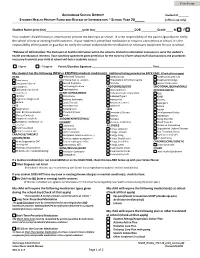

HEALTH HISTORY FORM and RELEASE of INFORMATION ~ SCHOOL YEAR 20_____ (Official Use Only)

ANCHORAGE SCHOOL DISTRICT Student ID_______ STUDENT HEALTH HISTORY FORM AND RELEASE OF INFORMATION ~ SCHOOL YEAR 20_____ (official use only) Student Name (print first) (print last) DOB Grade M F Your student’s health history is important to provide the best care at school. It is the responsibility of the parent /guardian to notify the school of new or existing health concerns. If your student is prescribed medication or requires a treatment at school, it is the responsibility of the parent or guardian to notify the school and provide the medication or necessary equipment for use at school. *Release of Information: The disclosure of health information within the school is limited to information necessary to serve the student’s health and education interests. Your voluntary agreement gives permission for the nurse to inform school staff of precautions and procedures necessary to protect your child at school and foster academic success. I Agree I Disagree Parent/Guardian Signature Date_________________ My student has the following (NEW or EXISTING) medical condition(s). Additional listing provided on BACK PAGE. (Check all that apply) HEAD Perforated Tympanic Osteoporosis Anaphylactic/peanuts Brain Injury Membrane (hole in eardrum) Rheumatoid Arthritis/Juvenile Anaphylactic/stings Concussion (loss of Speech Problems Scoliosis Lactose Intolerance consciousness) Swallowing Problem ENDOCRINE/BLOOD EMOTIONAL/BEHAVIORAL/ Concussion (no loss of Tracheostomy Clotting Defect PSYCHOLOGICAL consciousness) HEART/LUNGS/BRAIN Diabetes/Insulin Dependent