All Truth Is Worth Publishing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Latin America's Authoritarian Drift

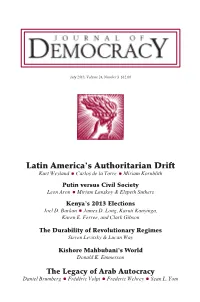

July 2013, Volume 24, Number 3 $12.00 Latin America’s Authoritarian Drift Kurt Weyland Carlos de la Torre Miriam Kornblith Putin versus Civil Society Leon Aron Miriam Lanskoy & Elspeth Suthers Kenya’s 2013 Elections Joel D. Barkan James D. Long, Karuti Kanyinga, Karen E. Ferree, and Clark Gibson The Durability of Revolutionary Regimes Steven Levitsky & Lucan Way Kishore Mahbubani’s World Donald K. Emmerson The Legacy of Arab Autocracy Daniel Brumberg Frédéric Volpi Frederic Wehrey Sean L. Yom Transforming The arab World’s ProTecTion-rackeT PoliTics Daniel Brumberg Daniel Brumberg is codirector of the Democracy and Governance Stud- ies program at Georgetown University and senior program officer at the Center for Conflict Management of the U.S. Institute of Peace. Despite the setbacks, conflicts, and violence that the Arab world has endured since the mass rebellions of early 2011, we can at least thank Egyptian heart surgeon turned television satirist Bassem Youssef for giving beleaguered democrats everywhere reason to smile. Even as prosecutors accused him of a host of “crimes”—including insulting the president and Islam itself—Youssef continued to lampoon the govern- ment. Taking a page from the previous regime’s playbook, prosecutors insisted that the courts were acting independently and that citizens rath- er than state officials had brought the charges. Invoking this ridiculous rationale, the police compelled Youssef to review tapes of his show in order to explain his jokes to his unamused interrogators. 1 Does this Kafkaesque tale leave any room for optimism? Watching an unchecked security apparatus regularly operate beyond the reach of a problematic legal system to harass journalists, some Egyptian writers argue that the very idea of transition is a hoax. -

New Tahrir Square (Planting Democracy)

Hochshule Anhalt (FH) Anhalt University of Applied Sciences Master of Landscape Architecture Anhalt University of Applied Sciences (October, 2013) New Tahrir Square (Planting Democracy) 3URI$OH[DQGHU0.DGHU¿UVWH[DPLQHU%\,VVDP$EG(OODWLI 3URI(LQDU.UHW]OHUVHFRQGH[DPLQHU Master of Landscape Architecture (MLA) '(&/$5$7,212)$87+256+,3 ,FHUWLI\WKDWWKHPDWHULDOFRQWDLQHGLQWKLV0DVWHU7KHVLVLVP\RZQZRUNDQGGRHVQRFRQWDLQXQDFNQRZOHGJHGZRUNRIRWKHUV :KHUH,KDYHFRQVXOWHGWKHSXEOLVKHGZRUNRIRWKHUVWKLVLVDOZD\VFOHDUO\DWWULEXWHG :KHUH,KDYHTXRWHGIURPWKHZRUNRIRWKHUVWKHVRXUFHLVDOZD\VJLYHQ:LWKWKHH[FHSWLRQRIVXFKTXRWDWLRQVWKH ZRUNRIWKLVWKHVLVLVHQWLUHO\P\RZQ 7KLVGLVVHUWDWLRQKDVQRWEHHQVXEPLWWHGIRUWKHDZDUGRIDQ\RWKHUGHJUHHRUGLSORPDLQDQ\RWKHULQVWLWXWLRQ __________________________________ ,VVDP$EG(OODWLI 6WXGHQW,' %HUQEXUJWKRI2FWREHU ABSTRACT Author: Issam Abd Ellatif !esis Title: New Tahrir Square (( PLANTING DEMOCRACY)) Keywords: Cairo, Tahrir, Planting democracy, revolution, February 2011. Abstract: Cairo give its tourists an unbelievable selection of attractions; it is a mixture of old and new as it include many former cities and their monuments.In fact the area of the city can be return to 4225 BC. cairo limited by the desert to the west and east,and the Nile delta to the north, the city is located on both banks and along 40km south to north of the river Nile. !e city centre is full of universities, governmental o#ces, institutions, commercial establishments, and countless hotels, creating a intensive pattern of constant activity. !e ever-busy Tahrir square is one of the major and largest public squares; the centre of the city. It's really di#cult task to come up with a proposal for Tahrir Square, the icon of the Egyptian revolution, which has not $nished yet. I develop proposals and for the tahrir square. Finally, I will present the design for the Egyptian Government, providing ideas, concepts and %at planes. I also propose solutions to current problems, by identifying potentials and taking advantages from them and by creating methods to pursuing these solutions. -

Egypt: Freedom on the Net 2017

FREEDOM ON THE NET 2017 Egypt 2016 2017 Population: 95.7 million Not Not Internet Freedom Status Internet Penetration 2016 (ITU): 39.2 percent Free Free Social Media/ICT Apps Blocked: Yes Obstacles to Access (0-25) 15 16 Political/Social Content Blocked: Yes Limits on Content (0-35) 15 18 Bloggers/ICT Users Arrested: Yes Violations of User Rights (0-40) 33 34 TOTAL* (0-100) 63 68 Press Freedom 2017 Status: Not Free * 0=most free, 100=least free Key Developments: June 2016 – May 2017 • More than 100 websites—including those of prominent news outlets and human rights organizations—were blocked by June 2017, with the figure rising to 434 by October (se Blocking and Filtering). • Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) services are restricted on most mobile connections, while repeated shutdowns of cell phone service affected residents of northern Sinai (Se Restrictions on Connectivity). • Parliament is reviewing a problematic cybercrime bill that could undermine internet freedom, and lawmakers separately proposed forcing social media users to register with the government and pay a monthly fee (see Legal Environment and Surveillance, Privacy, and Anonymity). • Mohamed Ramadan, a human rights lawyer, was sentenced to 10 years in prison and a 5-year ban on using the internet, in retaliation for his political speech online (see Prosecutions and Detentions for Online Activities). • Activists at seven human rights organizations on trial for receiving foreign funds were targeted in a massive spearphishing campaign by hackers seeking incriminating information about them (see Technical Attacks). 1 www.freedomonthenet.org Introduction FREEDOM EGYPT ON THE NET Obstacles to Access 2017 Introduction Availability and Ease of Access Internet freedom declined dramatically in 2017 after the government blocked dozens of critical news Restrictions on Connectivity sites and cracked down on encryption and circumvention tools. -

New Voices, New Directions

at Brookings Project on U.S. Relations with the Islamic World Saban Center for Middle East Policy at Brookings May 29-31, 2012 • Doha, Qatar 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20036 www.brookings.edu/about/projects/islamic-world NEW VOICES, NEW DIRECTIONS at Brookings WELCOME Ahlan Wa Sahlan! On behalf of the Brookings Project on U.S. Relations with the Islamic World, housed within the Saban Center for Middle East Policy, we welcome you to the ninth annual U.S.- Islamic World Forum. In partnership with the State of Qatar, Brookings convenes this Fo- rum annually under the gracious auspices of H.R.H. Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa Al-Thani, the Emir of Qatar. After a successful Forum convened for the first time in Washington, D.C. last year, we are pleased to be back in Doha. Last year, we met in the midst of the “Arab Awakening”—the dramatic changes that con- STEERING COMMITTEE tinue to transform the Middle East and North Africa. From Tunisia to Egypt to Yemen, ordinary citizens have made possible extraordinary political and social changes. This year, we examine the impact of, and continuing challenges posed by, these changes, not just for STEPHEN R. GRAND Fellow and Director the Arab world, but also for Muslim communities around the globe, including in South Project on U.S. Relations and Southeast Asia—as well as their strategic implications for the United States. with the Islamic World During our three days together, we have arranged a variety of formats for candid dialogue MARTIN INDYK and engagement: Vice President and Director -

Egypt's Unsustainable Crackdown

MEMO POLICY EGYPT’S UNSUSTAINABLE CRACKDOWN Anthony Dworkin and Hélène Michou Six months after the army deposed Egypt’s first freely SUMMARY As a referendum on the constitution approaches, elected president, the new authorities are keen to give Egyptian authorities are keen to give the the impression that the country is back on the path to impression that the country is back on track democracy. A new constitution has been drafted and will towards democracy. But the government’s be put to a referendum in mid-January. Parliamentary apparent effort to drive the Muslim Brotherhood completely out of public life and the repression of and presidential elections are scheduled to follow within alternative voices mean that a political solution the following six months. Egypt’s interim president, Adly to the country’s divisions remains far off. While Mansour, described the draft constitution as “a good start on there are uncertainties about the path that Egypt which to build the institutions of a democratic and modern will follow, these will play out within limits set by state”.1 Amr Moussa, chairman of the committee of 50 that the country’s powerful security forces. Against a background of popular intolerance and public was largely responsible for writing the constitution, said that media that strongly back the state, there is little it marked “the transition from disturbances to stability and prospect of the clampdown being lifted in the from economic stagnation to development”.2 short term. Yet it would be wrong to believe that Egypt’s current However, this path seems to promise only further instability and turbulence. -

Effects of American Pop Culture on the Political Stability of the Arab Spring! Mina Alsadoon

Santa Clara University Scholar Commons Advanced Writing: Pop Culture Intersections Student Scholarship 9-2-2019 Effects of American Pop Culture on the political stability of the Arab Spring! Mina Alsadoon Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/engl_176 Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, English Language and Literature Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Nonfiction Commons Recommended Citation Alsadoon, Mina, "Effects of American Pop Culture on the political stability of the Arab Spring!" (2019). Advanced Writing: Pop Culture Intersections. 35. https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/engl_176/35 This Research Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Advanced Writing: Pop Culture Intersections by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Santa Clara University Scholar Commons Advanced Writing: Pop Culture Intersections Student Scholarship 02-9-2019 Effects of American Pop Culture on the political stability of the Arab Spring! Mina Alsadoon Santa Clara University, [email protected] 2 Mina Alsadoon ENGL 106 Dr. Hendricks 28 August 2019 Effects of American Pop Culture on the political stability of the Arab Spring! "Mr. President... people have become like animals... We are living like dogs." (El General,2010) Powerful and strong words from a young Tunisian rapper his real unknown name is Hamada Ben Amor, his most famous song Rais Le Bled It was released at the end of 2010 when El General was attacking in it the former president Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali directly and his regime. -

Petition To: United Nations Working

PETITION TO: UNITED NATIONS WORKING GROUP ON ARBITRARY DETENTION Mr Mads Andenas (Norway) Mr José Guevara (Mexico) Ms Shaheen Ali (Pakistan) Mr Sètondji Adjovi (Benin) Mr Vladimir Tochilovsky (Ukraine) HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL UNITED NATIONS GENERAL ASSEMBLY COPY TO: UNITED NATIONS SPECIAL RAPPORTEUR ON THE PROMOTION AND PROTECTION OF THE RIGHT TO FREEDOM OF OPINION AND EXPRESSION, MR DAVID KAYE; UNITED NATIONS SPECIAL RAPPORTEUR ON THE RIGHTS TO FREEDOM OF PEACEFUL ASSEMBLY AND OF ASSOCIATION, MR MAINA KIAI; UNITED NATIONS SPECIAL RAPPORTEUR ON THE SITUATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENDERS, MR MICHEL FORST. in the matter of Alaa Abd El Fattah (the “Petitioner”) v. Egypt _______________________________________ Petition for Relief Pursuant to Commission on Human Rights Resolutions 1997/50, 2000/36, 2003/31, and Human Rights Council Resolutions 6/4 and 15/1 Submitted by: Media Legal Defence Initiative Electronic Frontier Foundation The Grayston Centre 815 Eddy Street 28 Charles Square San Francisco CA 94109 London N1 6HT BASIS FOR REQUEST The Petitioner is a citizen of the Arab Republic of Egypt (“Egypt”), which acceded to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (“ICCPR”) on 14 January 1982. 1 The Constitution of the Arab Republic of Egypt 2014 (the “Constitution”) states that Egypt shall be bound by the international human rights agreements, covenants and conventions it has ratified, which shall have the force of law after publication in accordance with the conditions set out in the Constitution. 2 Egypt is also bound by those principles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (“UDHR”) that have acquired the status of customary international law. -

Egypt Presidential Election Observation Report

EGYPT PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION OBSERVATION REPORT JULY 2014 This publication was produced by Democracy International, Inc., for the United States Agency for International Development through Cooperative Agreement No. 3263-A- 13-00002. Photographs in this report were taken by DI while conducting the mission. Democracy International, Inc. 7600 Wisconsin Avenue, Suite 1010 Bethesda, MD 20814 Tel: +1.301.961.1660 www.democracyinternational.com EGYPT PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION OBSERVATION REPORT July 2014 Disclaimer This publication is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of Democracy International, Inc. and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. CONTENTS CONTENTS ................................................................ 4 MAP OF EGYPT .......................................................... I ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................. II DELEGATION MEMBERS ......................................... V ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ....................... X EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.............................................. 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................ 6 ABOUT DI .......................................................... 6 ABOUT THE MISSION ....................................... 7 METHODOLOGY .............................................. 8 BACKGROUND ........................................................ 10 TUMULT -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Egyptian

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Egyptian Urban Exigencies: Space, Governance and Structures of Meaning in a Globalising Cairo A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Global Studies by Roberta Duffield Committee in charge: Professor Paul Amar, Chair Professor Jan Nederveen Pieterse Assistant Professor Javiera Barandiarán Associate Professor Juan Campo June 2019 The thesis of Roberta Duffield is approved. ____________________________________________ Paul Amar, Committee Chair ____________________________________________ Jan Nederveen Pieterse ____________________________________________ Javiera Barandiarán ____________________________________________ Juan Campo June 2014 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my thesis committee at the University of California, Santa Barbara whose valuable direction, comments and advice informed this work: Professor Paul Amar, Professor Jan Nederveen Pieterse, Professor Javiera Barandiarán and Professor Juan Campo, alongside the rest of the faculty and staff of UCSB’s Global Studies Department. Without their tireless work to promote the field of Global Studies and committed support for their students I would not have been able to complete this degree. I am also eternally grateful for the intellectual camaraderie and unending solidarity of my UCSB colleagues who helped me navigate Californian graduate school and come out the other side: Brett Aho, Amy Fallas, Tina Guirguis, Taylor Horton, Miguel Fuentes Carreño, Lena Köpell, Ashkon Molaei, Asutay Ozmen, Jonas Richter, Eugene Riordan, Luka Šterić, Heather Snay and Leila Zonouzi. I would especially also like to thank my friends in Cairo whose infinite humour, loyalty and love created the best dysfunctional family away from home I could ever ask for and encouraged me to enroll in graduate studies and complete this thesis: Miriam Afifiy, Eman El-Sherbiny, Felix Fallon, Peter Holslin, Emily Hudson, Raïs Jamodien and Thomas Pinney. -

Archiving a Revolution in the Digital Age, Archiving As an Act of Resistance

ESSAYS Archiving a Revolution in the Digital Age, Archiving as an Act of Resistance Lara Baladi 010_03 / 28 July 2016 Click the image above to enter Vox Populi: Tahrir Archives, a project by Lara Baladi * Archiving a Revolution in the Digital Age, Archiving as an Act of Resistance From the very first day of the 2011 uprisings in Egypt that toppled president Mubarak, archiving played a central role. During the 18 days of the revolution in Tahrir square, photographing was an act of seeing and recording. Almost simultaneously, because a photograph is intrinsically an archival document, this act of resistance turned into act of archiving history as it unfolded. In the square, revolting was archiving. From the media tent, at the centre of the square, protesters continuously uploaded footage and testimonies, thus reaching out to the rest of the world for solidarity. Artist and activist 1 of 17 h'p://www.ibraaz.org/essays/163 Tarek Hefny[1] created the website Thawra Media,[2] one of the first to host and disseminate as it happened documentation of the uprising. A media revolution also took place in Tahrir when the physical and the virtual space collapsed into one. Tahrir revealed the reality of the streets but also the reality of the virtual world. Friday of Victory, Tahrir Square, Cairo, Egypt, February 2011. Photo Lara Baladi. It was another normal day in September 1996 – a symphony of honking cars, people everywhere, dusty and hot. In the mid-1990s, at the height of the 'Made in China' invasion, I was searching for props in the Mouski, a vast open-air market in the heart of medieval Cairo. -

Banks of Downgraded S&P Rating Extends to Pharmaceuticals

AILY EWS MONDAY, MAY 13, 2013 N D ISSUE NO. 2190 NEWSTAND PRICE LE 4.00 EGYPT www.thedailynewsegypt.com Egypt’s Only Daily Independent Newspaper In English MENA COORDINATOR IN CAIRO A PASSIVE POWER RUNNIN’ ‘rOUND IN CAIRO White House coordinator for the Defence Minister Al-Sisi says the Cairo Runners’s half marathon Middle East, North Africa and the Armed Forces will not intervene in proved to be impressively Gulf Region Philip Gordon comes political affairs or begin policing organised, even while they ran in to Cairo 2 the streets 3 Egypt’s traffic-lawless streets 8 Central Bank receives $3bn Court to rule on Shura Council next month Qatari deposit for bonds The court said the verdict regarding the legality of the BONDS TO MATURE IN THREE YEARS WITH 3.5% INTEREST RATE Shura Council and Constituent Assembly, a case that began last year, will be announced on 2 June By Hend Kortam ing, forcing the court to suspend its activity. The Supreme Constitutional Court By the time the court reconvened will announce the verdict regarding the the new constitution had passed. status of the Shura Council on 2 June. The new constitution transfers full The case regarding the upper legislative authority to the Shura house of parliament had been re- Council until a new lower house, ferred to the State Commissioners renamed the House of Representa- Authority, an advisory panel of ex- tives, is elected. perts, to give its recommendations The constitution also bestows new since the status of the legislature has legislative powers on the council in changed after the adoption of the general, in addition to the ones it held constitution. -

THE ROAD AHEAD a Human Rights Agenda for Egypt’S New Parliament WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS THE ROAD AHEAD A Human Rights Agenda for Egypt’s New Parliament WATCH The Road Ahead A Human Rights Agenda for Egypt’s New Parliament Copyright © 2012 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-855-4 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JANUARY 2012 ISBN1-56432-855-4 The Road Ahead A Human Rights Agenda for Egypt’s New Parliament Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 1 Legislative Authority in Egypt Today ................................................................................... 3 The Need to Prioritize Legislative Reform to Ensure Basic Rights ........................................ 5 1. Repeal the Emergency Law and End the State of Emergency .................................................. 6 2. Amend the Code of Military Justice to End Military Trials of Civilians .................................... 11 3. Reform the Police Law ........................................................................................................