Securing Legitimate Stability in the Drc: External Assumptions and Local Perspectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Annex

ICC-01/04-01/10-396-Anx 02-09-2011 1/6 CB PT Public Annex ICC-01/04-01/10-396-Anx 02-09-2011 2/6 CB PT I. General contextual elements on the recent FLDR activities in the KIVUS: 1. Since the beginning of 2011, the FARDC conducted unilateral military operations under the “AMANI LEO” (peace today) operation against the FDLR and other armed groups in North Kivu, mainly in Walikale and Lubero territories, and in South Kivu, mainly in Fizi, Uvira and Shabunda territories. 1 2. The UN Group of Experts in its interim report on 7 June 2011 states that the FDLR remain militarily the strongest armed group in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.2 3. The UN Secretary-General further reported on 17 January 2011 that “the FDLR military leadership structure remained largely intact, and dispersed”.3 The FDLR established their presences in remote areas of eastern Maniema and northern Katanga provinces 4 and have sought to reinforce their presence in Rutshuru territory.5 4. The UN GoE reported as late as June 2011 on the FDLR’s continued recruitment 6 and training of mid-level commanders 7. The FDLR also 1 Para 5, page 2 S/2011/20, Report of the Secretary-General on the United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, 17 January 2011 (http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/2011/20 ), Para 32, page 9, S/2011/345 Interim report of the Group of Experts on the DRC submitted in accordance with paragraph 5 of Security Council resolution 1952 (2010), 7 June 2011 (http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/2011/345 -

DR Congo: Weekly Humanitarian Update 29 Januarychad - 02 February 2018

NIGERIA DR Congo: Weekly Humanitarian Update 29 JanuaryCHAD - 02 February 2018 HUMANITARIAN COORDINATOR BOLDUC WRAPS UP TANGANYIKA: UNFPA MEDICAL SUPPORT TO THE MISSION TO THE EAST PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENT CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC Humanitarian Coordinator Kim Bolduc, DR Congo’s most senior REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN The United Nations Population Fund, UNFPA, handed over five humanitarian official, on 5 February wrapped up her first mission tons of medical equipment to Tanganyika provincial authorities. to the Kasai region and Tanganyika Province, during which she The aid is intended for Nyunzu, Nyemba and Kansimba health took stock of humanitarian needs in these two provinces that are Nord-Ubangi Bas-Uele zones for tens of thousands of nursing and pregnant women as among the most affected by internal displacement. In Kasai, she Haut-Uele well as survivors of sexual violence. visited Matamba village whose population has swollen with the CAMEROON Sud-Ubangi MEASLES VACCINATION CAMPAIGN TARGETS OVER arrival of thousands of displaced people, mainly women and Mongala children. She heard testimonies from women who recounted 360,000 CHILDREN violence and rights violations as the region spiraled into a cycle of Ituri violence. She also visited a center run by a Congolese NGO that Tshopo South Kivu health services and humanitarian partners on Saturday REPUBLIC Equateur assists teenage girls who had been enrolled within armed groups. UGANDA OF have wrapped up a measles vaccination campaign targeting over In Kalemie, Bolduc visited the Katanyika site where some 13,000 GABON 360,000 children aged between 6 months old and 10 years in CONGO Nord-Kivu people have taken refuge following community violence. -

Le Président Du Conseil De Sécurité Présente

Le Président du Conseil de sécurité présente ses compliments aux membres du Conseil et a l'honneur de transmettre, pour information, le texte d'une lettre datée du 2 juin 2020, adressée au Président du Conseil de sécurité, par le Groupe d’experts sur la République démocratique du Congo reconduit suivant la résolution 2478 (2019) du Conseil de sécurité, ainsi que les pièces qui y sont jointes. Cette lettre et les pièces qui y sont jointes seront publiées comme document du Conseil de sécurité sous la cote S/2020/482. Le 2 juin 2020 The President of the Security Council presents his compliments to the members of the Council and has the honour to transmit herewith, for their information, a copy of a letter dated 2 June 2020 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo extended pursuant to Security Council resolution 2478 (2019) addressed to the President of the Security Council, and its enclosures. This letter and its enclosures will be issued as a document of the Security Council under the symbol S/2020/482. 2 June 2020 UNITED NATIONS NATIONS UNIES POSTAL ADDRESS-ADRESSE POSTALE: UNITED NATIONS, N.Y. 10017 CABLE ADDRESS -ADRESSE TELEGRAPHIQUE: UNATIONS NEWYORK REFERENCE: S/AC.43/2020/GE/OC.171 2 juin 2020 Monsieur Président, Les membres du Groupe d’experts sur la République démocratique du Congo, dont le mandat a été prorogé par le Conseil de sécurité dans sa résolution 2478 (2019), ont l’honneur de vous faire parvenir leur rapport final, conformément au paragraphe 4 de ladite résolution. -

Democratic Republic of Congo • North Kivu Situation Report No

Democratic Republic of Congo • North Kivu Situation Report No. 17 11 December 2012 This report is produced by OCHA in collaboration with humanitarian partners. It was issued by OCHADRC. It covers the period from 7 to 11 December 2012. The next report will be issued on or around 14 December. I. HIGHLIGHTS/ KEY PRIORITIES Over 900,000 people are currently living as displaced in North Kivu; an estimated 500,000 have been displaced since the FARDC-M23 crisis began in April WFP wraps up food distribution for 160,000 IDPs, more food on the way “Blanket” NFI distributions planned for IDPs living between Goma and Sake Some 250 schools looted or damaged in the Kivus since September IOM to take over coordination of spontaneous sites in and around Goma Humanitarian Coordinator visits Goma to take stock of humanitarian needs and challenges II. Situation Overview The situation in Goma remains calm but tense. M23 fighters, DRC : North Kivu who were to retreat to some 20 km outside of the city, are still maintaining positions close to Goma. The clashes that led to Goma’s take-over and its consequences, such as the break-out Mweso of over 1,000 prisoners and an accrued circulation of weapons, Walikale Rutshuru have created a climate of insecurity that is affecting thousands of Kitchanga NORD KIVU displaced people and delaying the return to normal life. Masisi Masisi Kirolirwe Armed men have on two successive days attacked houses close Kingi Kibumba to the Mugunga III IDP camp. The first attack took place on 9 Mushaki Nyiragongo Sake Kanyaruchinya December, one day after the Humanitarian Coordinator, Kibati Mutambiro Moustapha Soumaré, visited the camp which itself had been 10Km Bweremana RWANDA Presence of displaced persons looted a week earlier. -

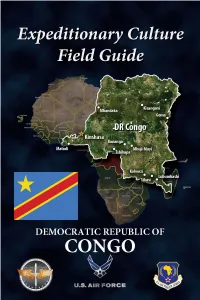

ECFG-DRC-2020R.Pdf

ECFG About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally t complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The he fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success. Democratic Republicof The guide consists of 2 parts: Part 1 introduces “Culture General,” the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment. Part 2 presents “Culture Specific” the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), focusing on unique cultural features of the DRC’s society and is designed to complement other pre-deployment training. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location (Photo courtesy of IRIN © Siegfried Modola). the For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact Congo AFCLC’s Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the expressed permission of the AFCLC. All photography is a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources as indicated. GENERAL CULTURE CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. A culture is the sum of all of the beliefs, values, behaviors, and symbols that have meaning for a society. -

The Ruzizi Plain

The Ruzizi Plain A CROSSROADS OF CONFLICT AND VIOLENCE Judith Verweijen, Juvénal Twaibu, Oscar Dunia Abedi and Alexis Ndisanze Ntababarwa INSECURE LIVELIHOODS SERIES / NOVEMBER 2020 Photo cover: Bar in Sange, Ruzizi Plain © Judith Verweijen 2017 The Ruzizi Plain A CROSSROADS OF CONFLICT AND VIOLENCE Judith Verweijen, Juvénal Twaibu, Oscar Dunia Abedi and Alexis Ndisanze Ntababarwa Executive summary The Ruzizi Plain in South Kivu Province has been the theatre of ongoing conflicts and violence for over two decades. Patterns and dynamics of con- flicts and violence have significantly evolved over time. Historically, conflict dynamics have largely centred on disputed customary authority – often framed in terms of intercommunity conflict. Violence was connected to these conflicts, which generated local security dilemmas. Consequently, armed groups mobilized to defend their commu- nity, albeit often at the behest of political and military entrepreneurs with more self-interested motives. At present, however, violence is mostly related to armed groups’ revenue-generation strategies, which involve armed burglary, robbery, assassinations, kidnappings for ransom and cattle-looting. Violence is also significantly nourished by interpersonal conflicts involving debt, family matters, and rivalries. In recent years, regional tensions and the activities of foreign armed groups and forces have become an additional factor of instability. Unfortunately, stabilization interventions have largely overlooked or been unable to address these changing drivers of violence. They have mostly focused on local conflict resolution, with less effort directed at addressing supra-local factors, such as the behaviour of political elites and the national army, and geopolitical tensions between countries in the Great Lakes Region. Future stabilization efforts will need to take these dimensions better into account. -

The Evolution of an Armed Movement in Eastern Congo Rift Valley Institute | Usalama Project

RIFT VALLEY INSTITUTE | USALAMA PROJECT UNDERSTANDING CONGOLESE ARMED GROUPS FROM CNDP TO M23 THE EVOLUTION OF AN ARMED MOVEMENT IN EASTERN CONGO rift valley institute | usalama project From CNDP to M23 The evolution of an armed movement in eastern Congo jason stearns Published in 2012 by the Rift Valley Institute 1 St Luke’s Mews, London W11 1Df, United Kingdom. PO Box 30710 GPO, 0100 Nairobi, Kenya. tHe usalama project The Rift Valley Institute’s Usalama Project documents armed groups in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The project is supported by Humanity United and Open Square and undertaken in collaboration with the Catholic University of Bukavu. tHe rift VALLEY institute (RVI) The Rift Valley Institute (www.riftvalley.net) works in Eastern and Central Africa to bring local knowledge to bear on social, political and economic development. tHe AUTHor Jason Stearns, author of Dancing in the Glory of Monsters: The Collapse of the Congo and the Great War of Africa, was formerly the Coordinator of the UN Group of Experts on the DRC. He is Director of the RVI Usalama Project. RVI executive Director: John Ryle RVI programme Director: Christopher Kidner RVI usalama project Director: Jason Stearns RVI usalama Deputy project Director: Willy Mikenye RVI great lakes project officer: Michel Thill RVI report eDitor: Fergus Nicoll report Design: Lindsay Nash maps: Jillian Luff printing: Intype Libra Ltd., 3 /4 Elm Grove Industrial Estate, London sW19 4He isBn 978-1-907431-05-0 cover: M23 soldiers on patrol near Mabenga, North Kivu (2012). Photograph by Phil Moore. rigHts: Copyright © The Rift Valley Institute 2012 Cover image © Phil Moore 2012 Text and maps published under Creative Commons license Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by/nc-nd/3.0. -

Ifrc.Org/Cgi/Pdf Appeals.Pl?Annual05/05AA035.Pdf

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO: 30 March 2005 CHOLERA IN SOUTH KIVU The Federation’s mission is to improve the lives of vulnerable people by mobilizing the power of humanity. It is the world’s largest humanitarian organization and its millions of volunteers are active in over 181 countries. In Brief Appeal No. 05EA004; Operations Update no. 2; Period covered: 24 February to 23 March 2005; Appeal coverage: 73.7%; (Click here to go directly to the attached Contributions List, also available on the website). Appeal history: · Launched on 24 February 2005 for CHF 285,000 (USD 217,000 or EUR 167,700) for four months to assist 200,000 beneficiaries. · Disaster Relief Emergency Funds (DREF) allocated: CHF 50,000. Outstanding needs: CHF 67,837 (USD 56,600 or EUR 43,800) Related Emergency or Annual Appeals: Democratic Republic of the Congo 2005 Annual Appeal no. 05AA035 – http://www.ifrc.org/cgi/pdf_appeals.pl?annual05/05AA035.pdf . Operational Summary: Cholera, endemic in South Kivu province since 1998, has resurfaced this year, with about 300 cases per week and with greater scope and duration. The most affected areas are in Bukavu and Uvira and Fizi territories. The Red Cross of the Democratic Republic of the Congo 1 has responded since the onset of this epidemic, and has shown progress in mitigating its effects. To better respond to the needs of the community, the Red Cross of DRC and the Federation launched this Emergency Appeal. Volunteers were deployed since 18 February 2005; they have assisted at water chlorination points and have revitalized awareness campaigns. -

The War Within the War

THE WAR WITHIN THE WAR Sexual Violence Against Women and Girls in Eastern Congo Human Rights Watch New York • Washington • London • Brussels 1 Copyright © June 2002 by Human Rights Watch. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-276-9 Library of Congress Control Number: 2002107517 Cover Photo: A woman in North Kivu who was assaulted by RCD soldiers in early 2002 and narrowly escaped rape. © 2002 Juliane Kippenberg/Human Rights Watch Cover design by Rafael Jiménez Addresses for Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th Floor, New York, NY 10118-3299 Tel: (212) 290-4700, Fax: (212) 736-1300, E-mail: [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500, Washington, DC 20009 Tel: (202) 612-4321, Fax: (202) 612-4333, E-mail: [email protected] 33 Islington High Street, N1 9LH London, UK Tel: (171) 713-1995, Fax: (171) 713-1800, E-mail: [email protected] 15 Rue Van Campenhout, 1000 Brussels, Belgium Tel: (2) 732-2009, Fax: (2) 732-0471, E-mail: [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org Listserv address: To subscribe to the Human Rights Watch news e-mail list, send a blank e-mail message to [email protected]. Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. -

He Who Touches the Weapon Becomes Other: a Study of Participation in Armed Groups in South Kivu, Democratic Republic of The

The London School of Economics and Political Science He who touches the weapon becomes other: A Study of Participation in Armed groups In South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo Gauthier Marchais A thesis submitted to the Department of International Development of the London School of Economics and Political Science for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. London, January 2016 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgment is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 107 254 words. Gauthier Marchais London, January 2016 2 Table of Contents ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................. 7 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ........................................................................................... 8 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 17 1.1. The persisting puzzle of participation in armed -

Ifrc.Org/Cgi/Pdf Appeals.Pl?Annual05/05AA035.Pdf

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO: 30 March 2005 CHOLERA IN SOUTH KIVU The Federation’s mission is to improve the lives of vulnerable people by mobilizing the power of humanity. It is the world’s largest humanitarian organization and its millions of volunteers are active in over 181 countries. In Brief Appeal No. 05EA004; Operations Update no. 2; Period covered: 24 February to 23 March 2005; Appeal coverage: 73.7%; (Click here to go directly to the attached Contributions List, also available on the website). Appeal history: · Launched on 24 February 2005 for CHF 285,000 (USD 217,000 or EUR 167,700) for four months to assist 200,000 beneficiaries. · Disaster Relief Emergency Funds (DREF) allocated: CHF 50,000. Outstanding needs: CHF 67,837 (USD 56,600 or EUR 43,800) Related Emergency or Annual Appeals: Democratic Republic of the Congo 2005 Annual Appeal no. 05AA035 – http://www.ifrc.org/cgi/pdf_appeals.pl?annual05/05AA035.pdf . Operational Summary: Cholera, endemic in South Kivu province since 1998, has resurfaced this year, with about 300 cases per week and with greater scope and duration. The most affected areas are in Bukavu and Uvira and Fizi territories. The Red Cross of the Democratic Republic of the Congo 1 has responded since the onset of this epidemic, and has shown progress in mitigating its effects. To better respond to the needs of the community, the Red Cross of DRC and the Federation launched this Emergency Appeal. Volunteers were deployed since 18 February 2005; they have assisted at water chlorination points and have revitalized awareness campaigns. -

Women's Bodies As a Battleground

Women’s Bodies as a Battleground: Sexual Violence Against Women and Girls During the War in the Democratic Republic of Congo South Kivu (1996-2003) Réseau des Femmes pour un Développement Associatif Réseau des Femmes pour la Défense des Droits et la Paix International Alert 2005 Réseau des Femmes pour un Développement Associatif (RFDA), Réseau des Femmes pour la Défense des Droits et la Paix (RFDP) and International Alert The Réseau des Femmes pour un Développement Associatif and the Réseau des Femmes pour la Défense des Droits et la Paix are based in Uvira and Bukavu respectively in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Both organisations have developed programmes on the issue of sexual violence, which include lobbying activities and the provision of support to women and girls that have been victims of this violence. The two organisations are in the process of creating a database concerning violations of women’s human rights. RFDA has opened several women’s refuges in Uvira, while RFDP, which is a founder member of the Coalition Contre les Violences Sexuelles en RDC (Coalition Against Sexual Violence in the DRC) is involved in advocacy work targeting the United Nations, national institutions and local administrative authorities in order to ensure the protection of vulnerable civilian populations in South Kivu, and in par- ticular the protection of women and their families. International Alert, a non-governmental organisation based in London, UK, works for the prevention and resolution of conflicts. It has been working in the Great Lakes region since 1995 and has established a programme there supporting women’s organisations dedicated to building peace and promoting women’s human rights.