Black Mesa State Park and Preserve Resource Management Plan 2013 [Updated April 2015]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mountains, Streams, and Lakes of Oklahoma I

Information Series #1, June 1998 Mountains, Streams, and Lakes of OklahomaI Kenneth S. Johnson2 INTRODUCTION valleys, hills, and plains throughout most of the re mainder of Oklahoma (Fig. 1). All the major lakes and Mountains and streams define the landscape of reservoirs of Oklahoma are man-made, and they are Oklahoma (Fig. 1). The mountains consist mainly of important for flood contr()l, water supply, recreation, resistant rock masses that were folded, faulted, and and generation of hydroelectric power. Natural lakes thrust upward in the geologic past (Fig. 2), whereas in Oklahoma are limited to oxbow lakes along major the streams have persisted in eroding less-resistant streams and to playa lakes in the High Plains region rock units and lowering the landscape to form broad of the west. Alphabetical List of20 Lakes with Largest Surface Area (from Oklahoma Water Atlas, Oklahoma Water Resources Board) 1. Broken Bow 11. Lake 0' The Cherokees 2. Canton 12. Oologah 3. Eufaula 13. Robert s. Kerr 4. Fort Gibson 14. Sardis 5. Foss 15. Skiatook 6. Great Salt Plains 16. Tenkiller Ferry ·7. Hudson 17. Texoma 8. Hugo 18. Waurika 9. Kaw 19. Webbers Falls 10. Keystone 20. Wister Modified from Historical Atlas of Oklahoma, by John W. Morris, Charles R. Goins, and Edwin C. 25 McReynolds. Copyright © 1986 by the University I of Oklahoma Press. o 40 80Km Figure 1. Mountains, streams, and principal lakes of Oklahoma. lReprinted from Oklahoma Geology Notes (1993), vol. 53, no. 5, p. 180-188. The Notes article was reprinted and expanded from Oklahoma Almanac, 1993-1994, Oklahoma Department of Lihraries, p. -

General Vertical Files Anderson Reading Room Center for Southwest Research Zimmerman Library

“A” – biographical Abiquiu, NM GUIDE TO THE GENERAL VERTICAL FILES ANDERSON READING ROOM CENTER FOR SOUTHWEST RESEARCH ZIMMERMAN LIBRARY (See UNM Archives Vertical Files http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmuunmverticalfiles.xml) FOLDER HEADINGS “A” – biographical Alpha folders contain clippings about various misc. individuals, artists, writers, etc, whose names begin with “A.” Alpha folders exist for most letters of the alphabet. Abbey, Edward – author Abeita, Jim – artist – Navajo Abell, Bertha M. – first Anglo born near Albuquerque Abeyta / Abeita – biographical information of people with this surname Abeyta, Tony – painter - Navajo Abiquiu, NM – General – Catholic – Christ in the Desert Monastery – Dam and Reservoir Abo Pass - history. See also Salinas National Monument Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Afghanistan War – NM – See also Iraq War Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Abrams, Jonathan – art collector Abreu, Margaret Silva – author: Hispanic, folklore, foods Abruzzo, Ben – balloonist. See also Ballooning, Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta Acequias – ditches (canoas, ground wáter, surface wáter, puming, water rights (See also Land Grants; Rio Grande Valley; Water; and Santa Fe - Acequia Madre) Acequias – Albuquerque, map 2005-2006 – ditch system in city Acequias – Colorado (San Luis) Ackerman, Mae N. – Masonic leader Acoma Pueblo - Sky City. See also Indian gaming. See also Pueblos – General; and Onate, Juan de Acuff, Mark – newspaper editor – NM Independent and -

Geologic Studies of Union County, New Mexico

Bulletin 63 New Mexico Bureau of Mines & Mineral Resources A DIVISION OF NEW MEXICO INSTITUTE OF MINING & TECHNOLOGY Geologic Studies of Union County, New Mexico by Brewster Baldwin and William R. Muehlberger SOCORRO 1959 NEW MEXICO INSTITUTE OF MINING & TECHNOLOGY KENNETH W. FORD, President NEW MEXICO BUREAU OF MINES & MINERAL RESOURCES FRANK E. KOTTLOWSKI, Director GEORGE S. Austin, Deputy Director BOARD OF REGENTS Ex Officio Bruce King, Governor of New Mexico Leonard DeLayo, Superintendent of Public Instruction Appointed William G. Abbott, Secretary-Treasurer, 1961-1985, Hobbs Judy Floyd, President, 1977-1981, Las Cruces Owen Lopez, 1977-1983, Santa Fe Dave Rice, 1972-1983, Carlsbad Steve Torres, 1967-1985, Socorro BUREAU STAFF Full Time MARLA D. ADKINS, Assistant Editor LYNNE MCNEIL, Staff Secretary ORIN J. ANDERSON, Geologist NORMA J. MEEKS, Department Secretary RUBEN ARCHULETA, Technician I ARLEEN MONTOYA, Librarian/Typist WILLIAM E. ARNOLD, Scientific Illustrator SUE NESS, Receptionist ROBERT A. BIEBERMAN, Senior Petrol. Geologist ROBERT M. NORTH, Mineralogist LYNN A. BRANDVOLD, Chemist JOANNE C. OSBURN, Geologist CORALE BRIEBLEY, Chemical Microbiologist GLENN R. OSBURN, Volcanologist BRENDA R. BROADWELL, Assoc. Lab Geoscientist LINDA PADILLA, Staff Secretary FRANK CAMPBELL, Coal Geologist JOAN C. PENDLETON, Associate Editor RICHARD CHAMBERLIN, Economic Geologist JUDY PERALTA, Executive Secretary CHARLES E. CHAPIN, Senior Geologist BARBARA R. Popp, Lab. Biotechnologist JEANETTE CHAVEZ, Admin. Secretary I ROBERT QUICK, Driller's Helper/Driller RICHARD R. CHAVEZ, Assistant Head, Petroleum MARSHALL A. REITER, Senior Geophyicist RUBEN A. CRESPIN, Laboratory Technician II JACQUES R. RENAULT, Senior Geologist Lois M. DEVLIN, Director, Bus.-Pub. Office JAMES M. ROBERTSON, Mining Geologist KATHY C. EDEN, Editorial Technician GRETCHEN H. -

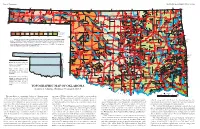

TOPOGRAPHIC MAP of OKLAHOMA Kenneth S

Page 2, Topographic EDUCATIONAL PUBLICATION 9: 2008 Contour lines (in feet) are generalized from U.S. Geological Survey topographic maps (scale, 1:250,000). Principal meridians and base lines (dotted black lines) are references for subdividing land into sections, townships, and ranges. Spot elevations ( feet) are given for select geographic features from detailed topographic maps (scale, 1:24,000). The geographic center of Oklahoma is just north of Oklahoma City. Dimensions of Oklahoma Distances: shown in miles (and kilometers), calculated by Myers and Vosburg (1964). Area: 69,919 square miles (181,090 square kilometers), or 44,748,000 acres (18,109,000 hectares). Geographic Center of Okla- homa: the point, just north of Oklahoma City, where you could “balance” the State, if it were completely flat (see topographic map). TOPOGRAPHIC MAP OF OKLAHOMA Kenneth S. Johnson, Oklahoma Geological Survey This map shows the topographic features of Oklahoma using tain ranges (Wichita, Arbuckle, and Ouachita) occur in southern contour lines, or lines of equal elevation above sea level. The high- Oklahoma, although mountainous and hilly areas exist in other parts est elevation (4,973 ft) in Oklahoma is on Black Mesa, in the north- of the State. The map on page 8 shows the geomorphic provinces The Ouachita (pronounced “Wa-she-tah”) Mountains in south- 2,568 ft, rising about 2,000 ft above the surrounding plains. The west corner of the Panhandle; the lowest elevation (287 ft) is where of Oklahoma and describes many of the geographic features men- eastern Oklahoma and western Arkansas is a curved belt of forested largest mountainous area in the region is the Sans Bois Mountains, Little River flows into Arkansas, near the southeast corner of the tioned below. -

Mosaic of New Mexico's Scenery, Rocks, and History

Mosaic of New Mexico's Scenery, Rocks, and History SCENIC TRIPS TO THE GEOLOGIC PAST NO. 8 Scenic Trips to the Geologic Past Series: No. 1—SANTA FE, NEW MEXICO No. 2—TAOS—RED RIVER—EAGLE NEST, NEW MEXICO, CIRCLE DRIVE No. 3—ROSWELL—CAPITAN—RUIDOSO AND BOTTOMLESS LAKES STATE PARK, NEW MEXICO No. 4—SOUTHERN ZUNI MOUNTAINS, NEW MEXICO No. 5—SILVER CITY—SANTA RITA—HURLEY, NEW MEXICO No. 6—TRAIL GUIDE TO THE UPPER PECOS, NEW MEXICO No. 7—HIGH PLAINS NORTHEASTERN NEW MEXICO, RATON- CAPULIN MOUNTAIN—CLAYTON No. 8—MOSlAC OF NEW MEXICO'S SCENERY, ROCKS, AND HISTORY No. 9—ALBUQUERQUE—ITS MOUNTAINS, VALLEYS, WATER, AND VOLCANOES No. 10—SOUTHWESTERN NEW MEXICO No. 11—CUMBRE,S AND TOLTEC SCENIC RAILROAD C O V E R : REDONDO PEAK, FROM JEMEZ CANYON (Forest Service, U.S.D.A., by John Whiteside) Mosaic of New Mexico's Scenery, Rocks, and History (Forest Service, U.S.D.A., by Robert W . Talbott) WHITEWATER CANYON NEAR GLENWOOD SCENIC TRIPS TO THE GEOLOGIC PAST NO. 8 Mosaic of New Mexico's Scenery, Rocks, a n d History edited by PAIGE W. CHRISTIANSEN and FRANK E. KOTTLOWSKI NEW MEXICO BUREAU OF MINES AND MINERAL RESOURCES 1972 NEW MEXICO INSTITUTE OF MINING & TECHNOLOGY STIRLING A. COLGATE, President NEW MEXICO BUREAU OF MINES & MINERAL RESOURCES FRANK E. KOTTLOWSKI, Director BOARD OF REGENTS Ex Officio Bruce King, Governor of New Mexico Leonard DeLayo, Superintendent of Public Instruction Appointed William G. Abbott, President, 1961-1979, Hobbs George A. Cowan, 1972-1975, Los Alamos Dave Rice, 1972-1977, Carlsbad Steve Torres, 1967-1979, Socorro James R. -

RV Sites in the United States Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile

RV sites in the United States This GPS POI file is available here: https://poidirectory.com/poifiles/united_states/accommodation/RV_MH-US.html Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile Camp Map 370 Lakeside Park Map 5 Star RV Map 566 Piney Creek Horse Camp Map 7 Oaks RV Park Map 8th and Bridge RV Map A AAA RV Map A and A Mesa Verde RV Map A H Hogue Map A H Stephens Historic Park Map A J Jolly County Park Map A Mountain Top RV Map A-Bar-A RV/CG Map A. W. Jack Morgan County Par Map A.W. Marion State Park Map Abbeville RV Park Map Abbott Map Abbott Creek (Abbott Butte) Map Abilene State Park Map Abita Springs RV Resort (Oce Map Abram Rutt City Park Map Acadia National Parks Map Acadiana Park Map Ace RV Park Map Ackerman Map Ackley Creek Co Park Map Ackley Lake State Park Map Acorn East Map Acorn Valley Map Acorn West Map Ada Lake Map Adam County Fairgrounds Map Adams City CG Map Adams County Regional Park Map Adams Fork Map Page 1 Location Map Adams Grove Map Adelaide Map Adirondack Gateway Campgroun Map Admiralty RV and Resort Map Adolph Thomae Jr. County Par Map Adrian City CG Map Aerie Crag Map Aeroplane Mesa Map Afton Canyon Map Afton Landing Map Agate Beach Map Agnew Meadows Map Agricenter RV Park Map Agua Caliente County Park Map Agua Piedra Map Aguirre Spring Map Ahart Map Ahtanum State Forest Map Aiken State Park Map Aikens Creek West Map Ainsworth State Park Map Airplane Flat Map Airport Flat Map Airport Lake Park Map Airport Park Map Aitkin Co Campground Map Ajax Country Livin' I-49 RV Map Ajo Arena Map Ajo Community Golf Course Map -

Camping Guide

GOING THE OKLAHOMA TODAY CAMPING BY SUSAN AND BILL DRAGOO E OF SOCIETY tent or under the stars is little about giant cottonwoods as they followed Anywhere in Oklahoma, outdoor primitive camping is permitted virtually are slaves, comfort and much about the temporary the bison; when cowboys slept by adventure is close at hand. Travelers are anywhere in the 350,000 acres of Okla- not so much liberation from what Washington Ir- campfires as they drove their herds unlikely to get bored with the same old homa’s portion of the Ouachita National to others as to ving called “our superfluities”—be they to market. landscape because of the state’s un- Forest alone. Beyond that, many local ourselves; our good wi-fi or the convenience of a ther- So it makes sense that Oklahoma of- usual natural diversity. Oklahoma has governments and private businesses offer superfluities are the chains that bind mostat—perhaps so we can ultimately fers a rich outdoor experience. This land, mountains, lakes, prairies, forests, rivers, camping and recreation opportunities. us, impeding every movement of our appreciate them all the more. which Irving described as containing and swamps in eleven ecoregions, and What better way to appreciate the state bodies, and thwarting every impulse Oklahomans are not so far re- “great grassy plains, interspersed with all of them have public lands well-suited than to backpack the Ouachita Trail or of our souls.” moved from the days when settlers forests and groves and clumps of trees, for camping. More than two million spend the night in a Panhandle oasis near —Washington Irving, 1835 traveled across Indian Territory on and watered by the Arkansas, the Grand acres lie in state parks, wildlife manage- the state’s highest point; camp in a cave the California Road, camping every Canadian, the Red River, and their ment areas, national forest, grasslands, or on a granite slab under the stars; or see Camping is illogical. -

Magyar Földrajzi Nevek Angol Nyelvre Fordítása

Magyar földrajzi nevek angol nyelvre fordítása Diplomamunka Térképész mesterszak készítette: Horváth Gábor Roland témavezető: Dr. Gercsák Gábor, egyetemi docens Térképtudományi és Geoinformatikai Tanszék Eötvös Loránd Tudományegyetem 2018. EÖTVÖS LORÁND TUDOMÁNYEGYETEM INFORMATIKAI KAR TÉRKÉPTUDOMÁNYI ÉS GEOINFORMATIKAI TANSZÉK DIPLOMAMUNKA-TÉMA BEJELENTŐ Név: Neptun kód: Szak: térképész MSc Témavezető neve: munkahelyének neve és címe: beosztása és iskolai végzettsége: A dolgozat címe: A témavezetést vállalom. .......................................................... (a témavezető aláírása) Kérem a diplomamunka témájának jóváhagyását. Budapest, 20…………………... ........................................................... (a hallgató aláírása) A diplomamunka-témát az Informatikai Kar jóváhagyta. Budapest, 20…………………… …………………………………….. (témát engedélyező tanszék vezetője) Tartalomjegyzék Címlap ..................................................................................................................................................... 1 Témabejelentő ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Tartalomjegyzék ...................................................................................................................................... 1 Bevezetés ................................................................................................................................................. 2 1. fejezet: A jelenlegi helyzet ............................................................................................................. -

Historic Resources of the Santa Fe Trail (Revised)

NPS Form 10-900-b (Rev. 01/2009) OMB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NPS Approved – April 3, 2013 National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (formerly 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items New Submission X Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Historic Resources of the Santa Fe Trail (Revised) B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) I. The Santa Fe Trail II. Individual States and the Santa Fe Trail A. International Trade on the Mexican Road, 1821-1846 A. The Santa Fe Trail in Missouri B. The Mexican-American War and the Santa Fe Trail, 1846-1848 B. The Santa Fe Trail in Kansas C. Expanding National Trade on the Santa Fe Trail, 1848-1861 C. The Santa Fe Trail in Oklahoma D. The Effects of the Civil War on the Santa Fe Trail, 1861-1865 D. The Santa Fe Trail in Colorado E. The Santa Fe Trail and the Railroad, 1865-1880 E. The Santa Fe Trail in New Mexico F. Commemoration and Reuse of the Santa Fe Trail, 1880-1987 C. Form Prepared by name/title KSHS Staff, amended submission; URBANA Group, original submission organization Kansas State Historical Society date Spring 2012 street & number 6425 SW 6th Ave. -

Northeastern New Mexico Offers Excellent Outdoor Adventures Catherine J

Page 6 Tuesday, June 25, 2019 The Chronicle-News Trinidad, Colorado Northeastern New Mexico offers excellent outdoor adventures Catherine J. Moser Refuge, the white-tailed and mule Features Editor deer populations are growing The Chronicle-News on the Refuge and may, at some point in the future, require man- agement. Interested individuals If you’re looking for some great should check at the Refuge office family-friendly outdoor summer on the current status of hunting activities it’s nice to know that on the refuge. you need not look any further n than your own backyard. The SANTA ROSA LAKE northeastern area of New Mexico STATE PARK in the state that’s known as the Santa Rosa Lake State Park, a Land of Enchantment has every- high plains Pecos River reservoir, thing there is to offer that will offers a variety of water sports. please any sport enthusiast. Anglers often catch bass, catfish, So, go ahead — gather up the and walleye. kids and get out there! You don’t n STORRIE LAKE STATE PARK want to miss a minute of all that New Mexico has waiting for you Favorable summer breezes at- do and see. tract colorful wind-surfing boards to Storrie Lake State Park, which is also popular for fishing and NM STATE PARKS AND boating. The visitor center fea- WILDLIFE AREAS tures historical exhibits about the Santa Fe Trail and 19th century n CIMARRON CANYON Las Vegas. STATE PARK Attractions: Set in New n SUMNER LAKE STATE PARK Mexico’s high country, where Sumner Lake State Park offers spectacular palisade cliffs and fishing for a variety of species, in- clear running waters dominate Photography by Pixabay cluding bass, crappie, channel cat- the landscape, Cimarron Canyon fish and the most abundant spe- State Park is part of the 33,116-acre Hiking Trail, Swimming Beach, Phone: 575-445-5607. -

Naturalhistory Tourism Map.Pdf

1. Cimarron Heritage Center *View features from road 11. Wedding Cake and Steamboat Buttes* The Cimarron Heritage Center is the go to museum in Boise City, OK. The museum is These large rock formations are shaped in a way that they resemble a wedding cake and located within the famous Cox House designed by architect Bruce Goff, who was a steamboat. The formations can be seen from miles away along Highway 456. Private property, protégé of the worldrenowned architect Frank Lloyd Wright. The museum buildings are view from road only. on the north end of town and can be easily spotted due to the large castiron dinosaur 12. Rabbit Ears Mountain* named “Cimmy” on the front lawn. There is a Dust Bowl exhibit, a collection of old tractors, Rabbit Ear(s) Mountain is along Highway 370 just north of Clayton, New Mexico and south of historical military displays, and dinosaur information as well as much more. The museum Clayton Lake State Park. The mountain resembles a pair of rabbit ears and can only be seen is open from Monday through Saturday at 10:00 am 12:00 pm and 1:00 pm 4:00 pm. from miles away due to its high elevation relative to the surrounding environment. Private Visit www.chcmuseumok.com or call at 5805443479. property, view from road only. 2. Rita Blanca National Grasslands Picnic Area 13. Clayton Lake State Park The Rita Blanca National Grassland is a Federally maintained grassland on the Great This 170 acre park has various activities for all ages. -

NORTHERN ARIZONA PROVINCE (024) by W.C

NORTHERN ARIZONA PROVINCE (024) By W.C. Butler INTRODUCTION This province covers about 59,000 sq mi, mostly in the southwestern part of the Colorado Plateau. Significant geologic features include the Grand Canyon, Kaibab Arch, Mogollon Highlands transition zone, Monument Uplift, Defiance Uplift, Black Mesa Basin, Holbrook Basin, and southern edges of the Kaiparowits and Blanding Basins. The stratigraphic section shown for northeastern Arizona has demonstrated the highest petroleum potential in Arizona. See Wilson (1962), Butler (1988a), and Dickinson (1989) for synopses of the province's geology and evolution. The lithologically and structurally complex basement of the Colorado Plateau area evolved from northwest-younging Proterozoic terranes sequentially accreted onto the Archean craton. As much as 12,000 ft of Middle and Late Proterozoic strata is preserved in possible rift-aulacogen depositional settings in central Arizona. Thick, unmetamorphosed, organic-rich Late Proterozoic strata deposited in backarc basins or continental lakes of north-central Arizona and south-central Utah have good petroleum potential. The plateau area, as a passive Paleozoic plate margin and buffered Mesozoic retro-arc platform, has been remarkably tectonically stable during Phanerozoic time. The area is characterized by blanket Paleozoic strata, as much as 6,000 ft thick, consisting of mostly shallow marine clastics and carbonates showing numerous disconformities. These strata accumulated during transgressions and regressions from both the northwest and southeast, onlapping and thinning toward the trans-continental arch – a northeast-trending positive area extending from the northeast into central Arizona. Convergence between North and South American tectonic plates, with reactivation of basement blocks, during the late Paleozoic created the plateau's fault-bounded basins and uplifts.