Scandinavian Defence and Alliance Policies: Different Together', in Anders Wivel and Peter Nedergaard (Eds): Routledge Handbook on Scandinavian Politics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of Conditions for Danish Defence Policy – Strategic Choices

centre for military studies university of copenhagen An Analysis of Conditions for Danish Defence Policy – Strategic Choices 2012 This analysis is part of the research-based services for public authorities carried out at the Centre for Military Studies for the parties to the Danish Defence Agreement. Its purpose is to analyse the conditions for Danish security policy in order to provide an objective background for a concrete discussion of current security and defence policy problems and for the long-term development of security and defence policy. The Centre for Military Studies is a research centre at the Department of —Political Science at the University of Copenhagen. At the centre research is done in the fields of security and defence policy and military strategy, and the research done at the centre forms the foundation for research-based services for public authorities for the Danish Ministry of Defence and the parties to the Danish Defence Agreement. This analysis is based on research-related method and its conclusions can —therefore not be interpreted as an expression of the attitude of the Danish Government, of the Danish Armed Forces or of any other authorities. Please find more information about the centre and its activities at: http://cms.polsci.ku.dk/. References to the literature and other material used in the analysis can be found at http://cms.polsci.ku.dk/. The original version of this analysis was published in Danish in April 2012. This version was translated to English by The project group: Major Esben Salling Larsen, Military Analyst Major Flemming Pradhan-Blach, MA, Military Analyst Professor Mikkel Vedby Rasmussen (Project Leader) Dr Lars Bangert Struwe, Researcher With contributions from: Dr Henrik Ø. -

Defence Budgets and Cooperation in Europe: Developments, Trends and Drivers

January 2016 Defence Budgets and Cooperation in Europe: Developments, Trends and Drivers Edited by Alessandro Marrone, Olivier De France, Daniele Fattibene Defence Budgets and Cooperation in Europe: Developments, Trends and Drivers Edited by Alessandro Marrone, Olivier De France and Daniele Fattibene Contributors: Bengt-Göran Bergstrand, FOI Marie-Louise Chagnaud, SWP Olivier De France, IRIS Thanos Dokos, ELIAMEP Daniele Fattibene, IAI Niklas Granholm, FOI John Louth, RUSI Alessandro Marrone, IAI Jean-Pierre Maulny, IRIS Francesca Monaco, IAI Paola Sartori, IAI Torben Schütz, SWP Marcin Terlikowski, PISM 1 Index Executive summary ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 Introduction ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 6 List of abbreviations --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 7 Chapter 1 - Defence spending in Europe in 2016 --------------------------------------------------------- 8 1.1 Bucking an old trend ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 8 1.2 Three scenarios ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 10 1.3 National data and analysis ---------------------------------------------------------------------------- 11 1.3.1 Central and Eastern Europe -------------------------------------------------------------------- 11 1.3.2 Nordic region -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

European Defence Cooperation After the Lisbon Treaty

DIIS REPORT 2015: 06 EUROPEAN DEFENCE COOPERATION AFTER THE LISBON TREATY The road is paved for increased momentum This report is written by Christine Nissen and published by DIIS as part of the Defence and Security Studies. Christine Nissen is PhD student at DIIS. DIIS · Danish Institute for International Studies Østbanegade 117, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark Tel: +45 32 69 87 87 E-mail: [email protected] www.diis.dk Layout: Lone Ravnkilde & Viki Rachlitz Printed in Denmark by Eurographic Danmark Coverphoto: EU Naval Media and Public Information Office ISBN 978-87-7605-752-7 (print) ISBN 978-87-7605-753-4 (pdf) © Copenhagen 2015, the author and DIIS Table of Contents Abbreviations 4 Executive summary / Resumé 5 Introduction 7 The European Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) 11 External Action after the Lisbon Treaty 12 Consequences of the Lisbon changes 17 The case of Denmark 27 – consequences of the Danish defence opt-out Danish Security and defence policy – outside the EU framework 27 Consequences of the Danish defence opt-out in a Post-Lisbon context 29 Conclusion 35 Bibliography 39 3 Abbreviations CFSP Common Foreign and Security Policy CPCC Civilian Planning and Conduct Capability CSDP Common Security and Defence Policy DEVCO European Commission – Development & Cooperation ECHO European Commission – Humanitarian Aid & Civil Protection ECJ European Court of Justice EDA European Defence Agency EEAS European External Action Service EMU Economic and Monetary Union EU The European Union EUMS EU Military Staff FAC Foreign Affairs Council HR High -

Trine Bramsen Minister of Defence 24 September 2020 Via E

Trine Bramsen Minister of Defence 24 September 2020 Via e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Dear Minister, Thank you for your letter dated 12 May 2020. I am writing on behalf of People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) Foundation and our US affiliate, which has more than 6.5 million members and supporters worldwide. We appreciate that the Danish armed forces have reduced their use of animals for live tissue training (LTT) from 110 animals in 2016 – as reported by the Danish Defence Command on 3 July 2020 pursuant to a citizen's request – to only nine animals in 2020. Considering how few animals have been used for LTT this year and given that a ratio of two to six students per animal (as stated in the new five-year "Militær traumatologi" LTT permit1) amounts to only 18 to 54 personnel undergoing the training this year, there is no significant investment in – or compelling justification for – using animals in LTT. Based on the information presented in this letter, we urge you to immediately suspend all use of animals for LTT while the Danish Armed Forces Medical Command conducts a comprehensive new evaluation of available non-animal trauma training methods to achieve full compliance with Directive 2010/63/EU and, in light of this evaluation, provide a definitive timeline for fully ending the Danish armed forces' use of animals for LTT. Danish Defence Command Does Not Have a List of LTT Simulation Models It Has Reviewed The aforementioned citizen's request asked for the following information: "[a] list of non-animal models that have been reviewed by the Danish Ministry of Defence for live tissue training (otherwise known as LTT or trauma training), with dates indicating when these reviews were conducted, and reasons why these non-animal models were rejected as full replacements to the use of animals for this training".2 1Animal Experiments Inspectorate, Ministry of Environment and Food. -

On the Way Towards a European Defence Union - a White Book As a First Step

DIRECTORATE-GENERAL FOR EXTERNAL POLICIES POLICY DEPARTMENT STUDY On the way towards a European Defence Union - A White Book as a first step ABSTRACT This study proposes a process, framed in the Lisbon Treaty, for the EU to produce a White Book (WB) on European defence. Based on document reviews and expert interviewing, this study details the core elements of a future EU Defence White Book: strategic objectives, necessary capabilities development, specific programs and measures aimed at achieving the improved capabilities, and the process and drafting team of a future European WB. The study synthesizes concrete proposals for each European institution, chief among which is calling on the European Council to entrust the High Representative with the drafting of the White Book. EP/EXPO/B/SEDE/2015/03 EN April 2016 - PE 535.011 © European Union, 2016 Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies This paper was requested by the European Parliament's Committee on Foreign Affairs and the Sub-Committee on Security and Defence. English-language manuscript was completed on 18 April 2016. Translated into FR/ DE. Printed in Belgium. Author(s): Prof. Dr. Javier SOLANA, President, ESADE Center for Global Economy and Geopolitics, Spain Prof. Dr. Angel SAZ-CARRANZA, Director, ESADE Center for Global Economy and Geopolitics, Spain María GARCÍA CASAS, Research Assistant, ESADE Center for Global Economy and Geopolitics, Spain Jose Francisco ESTÉBANEZ GÓMEZ, Research Assistant, ESADE Center for Global Economy and Geopolitics, Spain Official Responsible: Wanda TROSZCZYNSKA-VAN GENDEREN, Jérôme LEGRAND Editorial Assistants: Elina STERGATOU, Ifigeneia ZAMPA Feedback of all kind is welcome. Please write to: [email protected]. -

Military Security and Social Welfare in Denmark from 1848 to the Cold War Petersen, Klaus

www.ssoar.info The Welfare Defence: Military Security and Social Welfare in Denmark from 1848 to the Cold War Petersen, Klaus Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: GESIS - Leibniz-Institut für Sozialwissenschaften Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Petersen, K. (2020). The Welfare Defence: Military Security and Social Welfare in Denmark from 1848 to the Cold War. Historical Social Research, 45(2), 164-186. https://doi.org/10.12759/hsr.45.2020.2.164-186 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY Lizenz (Namensnennung) zur This document is made available under a CC BY Licence Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden (Attribution). For more Information see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de The Welfare Defence: Military Security and Social Welfare in Denmark from 1848 to the Cold War Klaus Petersen∗ Abstract: »Die Wohlfahrtsverteidigung: Militärische Sicherheit und Soziale Wohlfahrt in Dänemark von 1848 bis zum kalten Krieg«. In this article, I discuss the connection between security and social policy strategies in Denmark from 1848 up to the 1950s. Denmark is not the first country that comes to mind when discussing the connections between war, military conscription, and social reforms. Research into social reforms and the role war and the military play in this field has traditionally focused on superpowers and regional powers. The main argument in the article is that even though we do not find policy-makers legitimizing specific welfare reforms using security policy motives, or the mili- tary playing any significant role in policy-making, it is nevertheless relevant to discuss the links between war and welfare in Denmark. -

Contact to Delegates And

NATO Countries Delegate/POC e-mail Phone Fax Mr. SFC VAN EECKHOUT 0032 2 264 5735 0032 2 264 5774 Belgian Defence Kwartier Koningin Astrid Bruynstr. 1 Belgium B-1120 BRUSSEL [email protected] Mrs Lt Col NEDEVA +35 929 22 2235 0035 9888 79 77 21 Gen Staff of Bulgarian Armed Forces J2 34 Totleben Blvd SOFIA Bulgaria BULGARIA [email protected] Mrs. Maj McQuarrie 0061 3 996 7586 00613 992 1049 Directorate Human Rights & Diversity National Defence Headquarters HQ 101 Colonel By Drive OTTAWA, K1A 0K2 Canada CANADA [email protected] Mrs Lt Col GEDAYOVA 00420 923 210 327 00420 973 212 094 Ministry of Defence Joint Operations Center Vitezne namesti 5 160 00 PRAHA 6 Czech Republic CZECH REPUBLIC [email protected] Special Advisor Mrs CHRISTENSEN 0045 3266 5313 +45 3266 5599 Danish Defence Perosonnel Organization Sominegraven, Bldg 24 1439 COPENHAGEN DENMARK Denmark [email protected] Mrs Cpt KÜNNAPUU 3727171523 3725026019 General Staff of the Estonian Defence Forces Juhkentali 58 15007 Estonia TALLINN [email protected] Mr. Lt Col ADELL, 00331 72 69 20 89 00331 42 19 43 54 Etat-Major des Armees - ORH Rue Saint Dominique 14 00456 ARMEES France FRANCE [email protected] Cdr Mauersberger Federal Ministry of Defence Armed Forces Staff I 3 P.O. BOX 13 28 D- Germany 53003 BONN [email protected] Mrs Lt Col DIMITRIOU 0030 210 651 7648 Evolution Center Hellenic National General Staff Messogion Ave. 151 15500 HOLARGOS ATHENS Greece GREECE [email protected] 0030 210 6 57 62 46 Lt Col BALLAINE 0036 23 65 331 0036 23 65 111 / 26018 Közgazdasagi es Penzügyi Ügynökseg Aba uta 4. -

Defence Policy and the Armed Forces During the Pandemic Herunterladen

1 2 3 2020, Toms Rostoks and Guna Gavrilko In cooperation with the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung With articles by: Thierry Tardy, Michael Jonsson, Dominic Vogel, Elisabeth Braw, Piotr Szyman- ski, Robin Allers, Paal Sigurd Hilde, Jeppe Trautner, Henri Vanhanen and Kalev Stoicesku Language editing: Uldis Brūns Cover design and layout: Ieva Stūre Printed by Jelgavas tipogrāfija Cover photo: Armīns Janiks All rights reserved © Toms Rostoks and Guna Gavrilko © Authors of the articles © Armīns Janiks © Ieva Stūre © Uldis Brūns ISBN 978-9984-9161-8-7 4 Contents Introduction 7 NATO 34 United Kingdom 49 Denmark 62 Germany 80 Poland 95 Latvia 112 Estonia 130 Finland 144 Sweden 160 Norway 173 5 Toms Rostoks is a senior researcher at the Centre for Security and Strategic Research at the National Defence Academy of Latvia. He is also associate professor at the Faculty of Social Sciences, Univer- sity of Latvia. 6 Introduction Toms Rostoks Defence spending was already on the increase in most NATO and EU member states by early 2020, when the coronavirus epi- demic arrived. Most European countries imposed harsh physical distancing measures to save lives, and an economic downturn then ensued. As the countries of Europe and North America were cau- tiously trying to open up their economies in May 2020, there were questions about the short-term and long-term impact of the coro- navirus pandemic, the most important being whether the spread of the virus would intensify after the summer. With the number of Covid-19 cases rapidly increasing in September and October and with no vaccine available yet, governments in Europe began to impose stricter regulations to slow the spread of the virus. -

Land Forces Modernisation Projects 8 2.1 Denmark’S Defence Agreement 2018-2023 9 2.2 Hungary’S Zrinyi 2026 10 2.3 the United Kingdom’S to the Future and Beyond

Food for thought 03-2021 Land Forces Modernisation Challenges of Transformation Written by Miguel Gonzalez Buitrago Lucia Santabarbara AN EXPERTISE FORUM CONTRIBUTING TO EUROPEAN CONTRIBUTING TO FORUM AN EXPERTISE SINCE 1953 ARMIES INTEROPERABILITY European Army Interoperability Center Simone Rinaldi This paper was drawn up by Miguel Gonzalez Buitrago, Lucia Santabarbara and Sim- one Rinaldi under the supervision and guidance of Mr Mario Blokken, Director of the Permanent Secretariat. This Food for Thought paper is a document that gives an initial reflection on the theme. The content is not reflecting the positions of the member states but consists of elements that can initiate and feed the discussions and analyses in the domain of the theme. All our studies are available on www.finabel.org TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 Chapter 1: Military Doctrine and Warfare Scenarios 3 1.1 Unconventional Warfare 4 1.2 Asymmetric Warfare 6 1.3 Hybrid Warfare 7 Chapter 2: Land Forces Modernisation Projects 8 2.1 Denmark’s Defence Agreement 2018-2023 9 2.2 Hungary’s Zrinyi 2026 10 2.3 The United Kingdom’s to the Future and Beyond. 11 2.4 Greece’s Future Force Structure 2013-2027 12 2.5 Finland’s Total Defence 14 Chapter 3: Cutting edge technology: “Looking at the near future.” 15 3.1 Drones and Jammers 17 3.2 Drone Swarms 19 3.3 Hypersonic Weaponry 19 Chapter 4: Modernisation of Military Training 20 Conclusions 22 Bibliography 23 2 INTRODUCTION Land Force Modernisation is a process that omous systems. These may shape the nature entails changes of military equipment and ca- of conflict and facilitate ground forces oper- pacities at the strategic, operational, and tac- ations in challenging contexts. -

Danish Defence Expenditure 2021

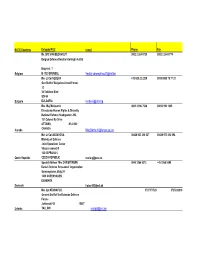

Danish Defence expenditure 2021 The total budget amounts to 26.4 billion DKK in 2021 according to the Danish Finance Act for 2021. The appropriations are primarily based on The Danish Defence Agreement 2018-2023 of January 28, 2018, Supplemental Agreement for the Danish Defence 2018-2023 of January 29, 2019 Agreement of new fighter aircraft of June 9, 2016. The appropriations are distributed among main accounts, activity areas and budget areas (see table 1- 3 below). Table 1: Overview of the appropriations 2019-2020 (current prices) and 2021-2024 (based on 2021 prices) Current prices Based on 2021 prices 2020 Year (Million DKK) 2019 (Accounting) (Accounting) 2021 2022 2023 2024 Total 23.516,0 25.225,0 26.383,2 26.928,3 29.463,2 26.256,6 12.11. Central management 414,7 503,0 1.561,6 1.891,9 2.321,6 2.134,5 Ministry of Defence 374,4 423,2 411,6 406,1 405,9 399,4 Central reserves and initiatives 1) 40,3 79,8 1.150,0 1.485,8 1.915,7 1.735,1 Reserves and budget regulation 2) - - - - - - 12.12. Personnel 1.935,4 1.944,8 1.941,6 1.932,6 1.917,0 1.899,3 Danish Defence Personnel Agency 393,1 398,9 402,0 402,9 408,2 402,9 Danish Defence Personnel Agency, Functional operations 966,0 939,7 965,3 950,6 913,8 886,5 Danish Defence Personnel Agency, Centrally Managed Units 90,8 58,4 61,4 61,4 61,4 61,4 Danish Defence Personnel Agency, Compensations 485,5 547,8 512,9 517,7 533,6 548,5 12.13. -

Mapping Evolving Internal Roles of the Armed Forces

SSR PAPER 7 Mapping Evolving Internal Roles of the Armed Forces Albrecht Schnabel and Marc Krupanski DCAF DCAF a centre for security, development and the rule of law SSR PAPER 7 Mapping Evolving Internal Roles of the Armed Forces Albrecht Schnabel and Marc Krupanski DCAF The Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF) is an international foundation whose mission is to assist the international community in pursuing good governance and reform of the security sector. The Centre develops and promotes norms and standards, conducts tailored policy research, identifies good practices and recommendations to promote democratic security sector governance, and provides in‐country advisory support and practical assistance programmes. SSR Papers is a flagship DCAF publication series intended to contribute innovative thinking on important themes and approaches relating to Security Sector Reform (SSR) in the broader context of Security Sector Governance (SSG). Papers provide original and provocative analysis on topics that are directly linked to the challenges of a governance‐driven security sector reform agenda. SSR Papers are intended for researchers, policy‐makers and practitioners involved in this field. ISBN 978‐92‐9222‐228‐4 © 2012 The Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces EDITORS Alan Bryden & Heiner Hänggi PRODUCTION Yury Korobovsky COPY EDITOR Cherry Ekins COVER IMAGE ©Bundeswehr/Rott. Soldiers of the German armed forces and members of the Federal Agency for Technical Relief (THW) secure a dam in an operation to protect against flooding in the Pechau area of the city of Magdeburg at the river Elbe The views expressed are those of the author(s) alone and do not in any way reflect the views of the institutions referred to or represented within this paper. -

Vom Kriege in Denmark

Brigadier General (ret.) Michael Hesselholt Clemmesen, "Observations of a lonely Clausewitzian convert: Vom Kriege in Denmark," pp.61-85, in Clausewitz Gesellschaft [Hamburg, Germany], Reiner Pommerin, ed., Clausewitz Goes Global: Carl von Clausewitz in the 21st Century, Commemorating the 50th Anniversary of the Clausewitz Gesellschaft (Berlin: Carola Hartmann Miles Verlag, 2011), ISBN: 9783937885414. MICHAEL HESSELHOLT CLEMMESEN, MA (hist.) Brigadier General (ret. Danish Army), was Director Strategy Department and Course Director of the Danish Joint Senior Command and Staff Course at the Royal Danish Defence College from 1991 till 1994 and creator and first Commandant of the Baltic Defence College from 1998 till 2004. He has since the late 1980's been lecturing military history, strategic theories and the realities of doctrinal development at staff and war college levels. Clemmesen is currently a senior research fellow at the Royal Danish Defence College Center of Military History. He has published numerous books and articles. His latest publication is (with the title translated from Danish): The Long Approach to 9. April. The History about the Forty Years prior to the German Operation against Denmark and Norway. Odense: The University Press of Southern Denmark, 2010). E-mails: [email protected] & [email protected]. This article is posted to The Clausewitz Homepage and to ClausewitzStudies.org with the kind permission of the publisher, Miles Verlag (Berlin), and of the Clausewitz Gesellschaft. See two reviews in German. SEE ALSO: Hans Delbrück and Peter Paret: Krieg, Geschichte, Theorie. Zwei Studien über Clausewitz. Herausgegeben von Peter Paret (Berlin: Miles- Verlag, 2018), 76 Seiten, erschienen als Hardcover mit Schutzumschlag und Paperback.