Defence Budgets and Cooperation in Europe: Trends and Investments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of Conditions for Danish Defence Policy – Strategic Choices

centre for military studies university of copenhagen An Analysis of Conditions for Danish Defence Policy – Strategic Choices 2012 This analysis is part of the research-based services for public authorities carried out at the Centre for Military Studies for the parties to the Danish Defence Agreement. Its purpose is to analyse the conditions for Danish security policy in order to provide an objective background for a concrete discussion of current security and defence policy problems and for the long-term development of security and defence policy. The Centre for Military Studies is a research centre at the Department of —Political Science at the University of Copenhagen. At the centre research is done in the fields of security and defence policy and military strategy, and the research done at the centre forms the foundation for research-based services for public authorities for the Danish Ministry of Defence and the parties to the Danish Defence Agreement. This analysis is based on research-related method and its conclusions can —therefore not be interpreted as an expression of the attitude of the Danish Government, of the Danish Armed Forces or of any other authorities. Please find more information about the centre and its activities at: http://cms.polsci.ku.dk/. References to the literature and other material used in the analysis can be found at http://cms.polsci.ku.dk/. The original version of this analysis was published in Danish in April 2012. This version was translated to English by The project group: Major Esben Salling Larsen, Military Analyst Major Flemming Pradhan-Blach, MA, Military Analyst Professor Mikkel Vedby Rasmussen (Project Leader) Dr Lars Bangert Struwe, Researcher With contributions from: Dr Henrik Ø. -

Defence Budgets and Cooperation in Europe: Developments, Trends and Drivers

January 2016 Defence Budgets and Cooperation in Europe: Developments, Trends and Drivers Edited by Alessandro Marrone, Olivier De France, Daniele Fattibene Defence Budgets and Cooperation in Europe: Developments, Trends and Drivers Edited by Alessandro Marrone, Olivier De France and Daniele Fattibene Contributors: Bengt-Göran Bergstrand, FOI Marie-Louise Chagnaud, SWP Olivier De France, IRIS Thanos Dokos, ELIAMEP Daniele Fattibene, IAI Niklas Granholm, FOI John Louth, RUSI Alessandro Marrone, IAI Jean-Pierre Maulny, IRIS Francesca Monaco, IAI Paola Sartori, IAI Torben Schütz, SWP Marcin Terlikowski, PISM 1 Index Executive summary ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 Introduction ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 6 List of abbreviations --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 7 Chapter 1 - Defence spending in Europe in 2016 --------------------------------------------------------- 8 1.1 Bucking an old trend ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 8 1.2 Three scenarios ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 10 1.3 National data and analysis ---------------------------------------------------------------------------- 11 1.3.1 Central and Eastern Europe -------------------------------------------------------------------- 11 1.3.2 Nordic region -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

European Defence Cooperation After the Lisbon Treaty

DIIS REPORT 2015: 06 EUROPEAN DEFENCE COOPERATION AFTER THE LISBON TREATY The road is paved for increased momentum This report is written by Christine Nissen and published by DIIS as part of the Defence and Security Studies. Christine Nissen is PhD student at DIIS. DIIS · Danish Institute for International Studies Østbanegade 117, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark Tel: +45 32 69 87 87 E-mail: [email protected] www.diis.dk Layout: Lone Ravnkilde & Viki Rachlitz Printed in Denmark by Eurographic Danmark Coverphoto: EU Naval Media and Public Information Office ISBN 978-87-7605-752-7 (print) ISBN 978-87-7605-753-4 (pdf) © Copenhagen 2015, the author and DIIS Table of Contents Abbreviations 4 Executive summary / Resumé 5 Introduction 7 The European Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) 11 External Action after the Lisbon Treaty 12 Consequences of the Lisbon changes 17 The case of Denmark 27 – consequences of the Danish defence opt-out Danish Security and defence policy – outside the EU framework 27 Consequences of the Danish defence opt-out in a Post-Lisbon context 29 Conclusion 35 Bibliography 39 3 Abbreviations CFSP Common Foreign and Security Policy CPCC Civilian Planning and Conduct Capability CSDP Common Security and Defence Policy DEVCO European Commission – Development & Cooperation ECHO European Commission – Humanitarian Aid & Civil Protection ECJ European Court of Justice EDA European Defence Agency EEAS European External Action Service EMU Economic and Monetary Union EU The European Union EUMS EU Military Staff FAC Foreign Affairs Council HR High -

Assessment and Selection Process for the Bulgarian Special Forces

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive DSpace Repository Theses and Dissertations 1. Thesis and Dissertation Collection, all items 2019-12 ASSESSMENT AND SELECTION PROCESS FOR THE BULGARIAN SPECIAL FORCES Vlahov, Petar Georgiev Monterey, CA; Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/64090 Downloaded from NPS Archive: Calhoun NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS ASSESSMENT AND SELECTION PROCESS FOR THE BULGARIAN SPECIAL FORCES by Petar Georgiev Vlahov December 2019 Thesis Advisor: Kalev I. Sepp Second Reader: Michael Richardson Approved for public release. Distribution is unlimited. THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Form Approved OMB REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington, DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED (Leave blank) December 2019 Master’s thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS ASSESSMENT AND SELECTION PROCESS FOR THE BULGARIAN SPECIAL FORCES 6. AUTHOR(S) Petar Georgiev Vlahov 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING Naval Postgraduate School ORGANIZATION REPORT Monterey, CA 93943-5000 NUMBER 9. SPONSORING / MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND 10. -

Armed Forces As an Element of National Power, and Compulsory Military Service

Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies Volume: 3 – Issue: 4 – October - 2013 Armed Forces as an Element of National Power, and Compulsory Military Service Suat Begeç, Turkey Abstract Whether military service should be done as a national duty or left to the professionals has been discussed for a long time both in Turkey and across the world. In order to answer this question and make relevant suggestions, this paper begins with the recruitment system in the Turkish Armed Forces during the history. Subsequently, armed forces of neighbor countries, their communication strategies and of those politically linked with Turkey as well as the world armies carrying weight for the scope of this study are all analyzed. Thirdly, current military service and its flawed aspects are explained. Finally come suggestions on how the military service should be. Keywords: Armed forces, compulsory military service, national army, recruitment © Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies 179 Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies Volume: 3 – Issue: 4 – October - 2013 Introduction Neither numbers nor technology wins in a war… The winner is always the heart. There is no might that can stand against a unit banded together. Soldiers believe that if they lose their life in a war, they will die a martyr and be worthy of heaven; and that if they survive they will be a veteran and leave unforgettable memories to his children. This belief renders them fearless. This bestows on their commanders a power that few leaders have. Power is the ability to influence people and events. Power is the ability that leaders and managers gain and enjoy through their personalities, activities and situations within the organizational structure [Newstrom & Davis, 2002:272]. -

Trine Bramsen Minister of Defence 24 September 2020 Via E

Trine Bramsen Minister of Defence 24 September 2020 Via e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Dear Minister, Thank you for your letter dated 12 May 2020. I am writing on behalf of People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) Foundation and our US affiliate, which has more than 6.5 million members and supporters worldwide. We appreciate that the Danish armed forces have reduced their use of animals for live tissue training (LTT) from 110 animals in 2016 – as reported by the Danish Defence Command on 3 July 2020 pursuant to a citizen's request – to only nine animals in 2020. Considering how few animals have been used for LTT this year and given that a ratio of two to six students per animal (as stated in the new five-year "Militær traumatologi" LTT permit1) amounts to only 18 to 54 personnel undergoing the training this year, there is no significant investment in – or compelling justification for – using animals in LTT. Based on the information presented in this letter, we urge you to immediately suspend all use of animals for LTT while the Danish Armed Forces Medical Command conducts a comprehensive new evaluation of available non-animal trauma training methods to achieve full compliance with Directive 2010/63/EU and, in light of this evaluation, provide a definitive timeline for fully ending the Danish armed forces' use of animals for LTT. Danish Defence Command Does Not Have a List of LTT Simulation Models It Has Reviewed The aforementioned citizen's request asked for the following information: "[a] list of non-animal models that have been reviewed by the Danish Ministry of Defence for live tissue training (otherwise known as LTT or trauma training), with dates indicating when these reviews were conducted, and reasons why these non-animal models were rejected as full replacements to the use of animals for this training".2 1Animal Experiments Inspectorate, Ministry of Environment and Food. -

SPECIAL REPORT No

SPECIAL REPORT NO. 225 | MARCH 25, 2020 China’s Defense Budget in Context: How Under-Reporting and Differing Standards and Economies Distort the Picture Frederico Bartels China’s Defense Budget in Context: How Under-Reporting and Differing Standards and Economies Distort the Picture Frederico Bartels SPECIAL REPORT No. 225 | MARCH 25, 2020 CENTER FOR NATIONAL DEFENSE This paper, in its entirety, can be found at http://report.heritage.org/sr225 The Heritage Foundation | 214 Massachusetts Avenue, NE | Washington, DC 20002 | (202) 546-4400 | heritage.org Nothing written here is to be construed as necessarily reflecting the views of The Heritage Foundation or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before Congress. SPECIAL REPORT | No. 225 MARCH 25, 2020 | 1 heritage.org China’s Defense Budget in Context: How Under-Reporting and Differing Standards and Economies Distort the Picture Frederico Bartels he aim of this Special Report is to bring transparency to comparisons between American and Chinese military expenditures. The challenges T posed by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and its military will likely only increase in the coming years; the democratic world needs to be aware of those challenges and its build-up in order to effectively respond. The Department of Defense needs to reorient itself fully to face the threats posed by China. The United States should continuously shine a light on the CCP’s military activities and its military build-up. The government should also make more of its data on China’s military expenditures available to the public in order to build awareness of the challenge. -

On the Way Towards a European Defence Union - a White Book As a First Step

DIRECTORATE-GENERAL FOR EXTERNAL POLICIES POLICY DEPARTMENT STUDY On the way towards a European Defence Union - A White Book as a first step ABSTRACT This study proposes a process, framed in the Lisbon Treaty, for the EU to produce a White Book (WB) on European defence. Based on document reviews and expert interviewing, this study details the core elements of a future EU Defence White Book: strategic objectives, necessary capabilities development, specific programs and measures aimed at achieving the improved capabilities, and the process and drafting team of a future European WB. The study synthesizes concrete proposals for each European institution, chief among which is calling on the European Council to entrust the High Representative with the drafting of the White Book. EP/EXPO/B/SEDE/2015/03 EN April 2016 - PE 535.011 © European Union, 2016 Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies This paper was requested by the European Parliament's Committee on Foreign Affairs and the Sub-Committee on Security and Defence. English-language manuscript was completed on 18 April 2016. Translated into FR/ DE. Printed in Belgium. Author(s): Prof. Dr. Javier SOLANA, President, ESADE Center for Global Economy and Geopolitics, Spain Prof. Dr. Angel SAZ-CARRANZA, Director, ESADE Center for Global Economy and Geopolitics, Spain María GARCÍA CASAS, Research Assistant, ESADE Center for Global Economy and Geopolitics, Spain Jose Francisco ESTÉBANEZ GÓMEZ, Research Assistant, ESADE Center for Global Economy and Geopolitics, Spain Official Responsible: Wanda TROSZCZYNSKA-VAN GENDEREN, Jérôme LEGRAND Editorial Assistants: Elina STERGATOU, Ifigeneia ZAMPA Feedback of all kind is welcome. Please write to: [email protected]. -

Military Security and Social Welfare in Denmark from 1848 to the Cold War Petersen, Klaus

www.ssoar.info The Welfare Defence: Military Security and Social Welfare in Denmark from 1848 to the Cold War Petersen, Klaus Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: GESIS - Leibniz-Institut für Sozialwissenschaften Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Petersen, K. (2020). The Welfare Defence: Military Security and Social Welfare in Denmark from 1848 to the Cold War. Historical Social Research, 45(2), 164-186. https://doi.org/10.12759/hsr.45.2020.2.164-186 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY Lizenz (Namensnennung) zur This document is made available under a CC BY Licence Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden (Attribution). For more Information see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de The Welfare Defence: Military Security and Social Welfare in Denmark from 1848 to the Cold War Klaus Petersen∗ Abstract: »Die Wohlfahrtsverteidigung: Militärische Sicherheit und Soziale Wohlfahrt in Dänemark von 1848 bis zum kalten Krieg«. In this article, I discuss the connection between security and social policy strategies in Denmark from 1848 up to the 1950s. Denmark is not the first country that comes to mind when discussing the connections between war, military conscription, and social reforms. Research into social reforms and the role war and the military play in this field has traditionally focused on superpowers and regional powers. The main argument in the article is that even though we do not find policy-makers legitimizing specific welfare reforms using security policy motives, or the mili- tary playing any significant role in policy-making, it is nevertheless relevant to discuss the links between war and welfare in Denmark. -

TNE21 Bio Sheet

1 & 2 JUNE 2021 – VIRTUAL EVENT SPEAKER BIOGRAPHIES Brigadier general João António Campos Rocha Director of CIS, EMGFA, Portugal Brigadier general electrotechnical engineer João António Campos Rocha was born in Albufeira, Portugal, in February 1965. He belongs to the Air Force and became the Director of Communications and Information Systems of the General Staff of the Armed Forces since January of 2019. REAR-ADMIRAL MÁRIO DO CARMO DURÃO POR N (Ret.), President, AFCEA Portugal Chapter Rear-Admiral Mário Durão, graduated from Naval Academy in June 1971 and from Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, USA, as Master of Science in Mechanical Engineering in June 1977. Between 1984 and 1994, was appointed Professor of Thermodynamics and Fluid Mechanics at the Naval Academy. From 1994 to 2005, assumed top management functions in the ICT areas in the Navy and the MoD, being CIO and Deputy Secretary General. He retired in December 2013. Since October 2014 he has been president of AFCEA Portugal. 1 KC CHOI B2B Global Lead, Samsung Electronics, USA Executive Vice President, Head of Global Mobile B2B/B2G Team, Mobile Communications Business, Samsung Electronics Co.,Ltd (Nov, 2019~present). 35 years working at several of America’s iconic technology companies such as IBM, NCR, HP and Dell and CTO for United Healthcare. B.A. in Economics and Electrical Engineering from UC Irvine, Guest lecturer at Loyola Marymount University and Stanford University. MGen Jorge Côrte-Real Andrade Deputy Director of National Defence Resources Directorate, Ministry of Defence, Portugal MGen Jorge Côrte-Real is Deputy Director of the Portuguese Defence Resources Directorate (MoD) and Deputy National Armament Director. -

Contact to Delegates And

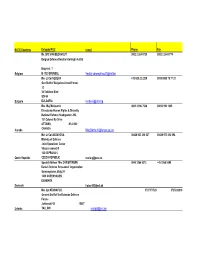

NATO Countries Delegate/POC e-mail Phone Fax Mr. SFC VAN EECKHOUT 0032 2 264 5735 0032 2 264 5774 Belgian Defence Kwartier Koningin Astrid Bruynstr. 1 Belgium B-1120 BRUSSEL [email protected] Mrs Lt Col NEDEVA +35 929 22 2235 0035 9888 79 77 21 Gen Staff of Bulgarian Armed Forces J2 34 Totleben Blvd SOFIA Bulgaria BULGARIA [email protected] Mrs. Maj McQuarrie 0061 3 996 7586 00613 992 1049 Directorate Human Rights & Diversity National Defence Headquarters HQ 101 Colonel By Drive OTTAWA, K1A 0K2 Canada CANADA [email protected] Mrs Lt Col GEDAYOVA 00420 923 210 327 00420 973 212 094 Ministry of Defence Joint Operations Center Vitezne namesti 5 160 00 PRAHA 6 Czech Republic CZECH REPUBLIC [email protected] Special Advisor Mrs CHRISTENSEN 0045 3266 5313 +45 3266 5599 Danish Defence Perosonnel Organization Sominegraven, Bldg 24 1439 COPENHAGEN DENMARK Denmark [email protected] Mrs Cpt KÜNNAPUU 3727171523 3725026019 General Staff of the Estonian Defence Forces Juhkentali 58 15007 Estonia TALLINN [email protected] Mr. Lt Col ADELL, 00331 72 69 20 89 00331 42 19 43 54 Etat-Major des Armees - ORH Rue Saint Dominique 14 00456 ARMEES France FRANCE [email protected] Cdr Mauersberger Federal Ministry of Defence Armed Forces Staff I 3 P.O. BOX 13 28 D- Germany 53003 BONN [email protected] Mrs Lt Col DIMITRIOU 0030 210 651 7648 Evolution Center Hellenic National General Staff Messogion Ave. 151 15500 HOLARGOS ATHENS Greece GREECE [email protected] 0030 210 6 57 62 46 Lt Col BALLAINE 0036 23 65 331 0036 23 65 111 / 26018 Közgazdasagi es Penzügyi Ügynökseg Aba uta 4. -

Bulgaria – National Report

Bulgaria – National Report Since the Republic of Bulgaria is one of the newly accepted NATO members, the main purpose of this report is to give basic information on women in the Bulgarian Armed Forces. It will briefly review the historic background of the issue, the legal regulations concerning women in uniform as well as their current status in the armed forces. Introduction In our modern history examples of women taking part in military units date back to the Russian-Turkish war of 1877-1878 as well as to the Serb-Bulgarian War of 1885. Nevertheless, their organized participation in activities supporting the army began at the beginning of the 20th century. In 1912, when the First Balkan War was declared, the Bulgarian Red Cross organized short sanitary courses in some of the big cities. Many women volunteers, called “Samaritans”, attended those courses and after that were sent to field hospitals and small medical compartments close to the front lines. One of them was the first woman in the world to take part in a combat flight on Oct 30th 1912. At this same time Bulgarian women took also part in infantry units, fighting shoulder to shoulder with their brothers and husbands. Thirty years later, in 1944, when Bulgaria joined the anti-Nazi coalition, 4200 women voluntarily participated in Bulgarian military units, 800 of them being directly engaged in combat activities. Others served as doctors, nurses, military correspondents and even as actresses in the front theatres. As a part of the constitutional changes in the country after the end of the Second World War, discrimination based on sex was banned and women were officially given the right to practice the military profession.