India and Sunda Plates Motion and Deformation Along Their Boundary In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Along the Sumatran Fault System Derived from GNSS

Ito et al. Earth, Planets and Space (2016) 68:57 DOI 10.1186/s40623-016-0427-z LETTER Open Access Co‑seismic offsets due to two earthquakes (Mw 6.1) along the Sumatran fault system derived from GNSS measurements Takeo Ito1* , Endra Gunawan2, Fumiaki Kimata3, Takao Tabei4, Irwan Meilano2, Agustan5, Yusaku Ohta6, Nazli Ismail7, Irwandi Nurdin7 and Didik Sugiyanto7 Abstract Since the 2004 Sumatra–Andaman earthquake (Mw 9.2), the northwestern part of the Sumatran island has been a high seismicity region. To evaluate the seismic hazard along the Great Sumatran fault (GSF), we installed the Aceh GNSS network for the Sumatran fault system (AGNeSS) in March 2005. The AGNeSS observed co-seismic offsets due to the April 11, 2012 Indian Ocean earthquake (Mw 8.6), which is the largest intraplate earthquake recorded in history. The largest offset at the AGNeSS site was approximately 14.9 cm. Two Mw 6.1 earthquakes occurred within AGNeSS in 2013, one on January 21 and the other on July 2. We estimated the fault parameters of the two events using a Markov chain Monte Carlo method. The estimated fault parameter of the first event was a right-lateral strike-slip where the strike was oriented in approximately the same direction as the surface trace of the GSF. The estimated peak value of the probability density function for the static stress drop was approximately 0.7 MPa. On the other hand, the co-seis- mic displacement fields of the second event from nearby GNSS sites clearly showed a left-lateral motion on a north- east–southwest trending fault plane and supported the contention that the July 2 event broke at the conjugate fault of the GSF. -

Buidling Response to Long-Distance Major Earthquakes

13th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering Vancouver, B.C., Canada August 1-6, 2004 Paper No. 804 BUILDING RESPONSE TO LONG-DISTANCE MAJOR EARTHQUAKES T.-C. PAN1, X. T. YOU2 and K. W. CHENG3 SUMMARY Singapore is believed to be located in an aseismic region. However, tremors caused by distant Sumatra earthquakes have reportedly been felt in Singapore for many years. Based on previous studies for Singapore, the maximum credible earthquakes (MCEs) from Sumatra have been hypothesized to be a subduction earthquake (Mw = 9.0) and a strike-slip earthquake (Mw = 7.5). Response at a soft soil site in Singapore to the synthetic bedrock motions corresponding to these maximum credible earthquakes are simulated using a one-dimensional wave propagation method based on the equivalent-linear technique. A typical high-rise residential building in Singapore is analyzed to study its responses subjected to the MCE ground motions at both the rock site and the soft soil site. The results show that the base shear force ratios would exceed the local code requirement on the notional horizontal load for buildings. Because of the large aspect ratio of the floor plan of the typical building, the effects of flexible diaphragms are also included in the seismic response analyses. INTRODUCTION The 1985 Michoacan earthquake, in which a large earthquake (Ms = 8.1) along the coast of Mexico, caused destructions and loss of lives in Mexico City, 350 km away from the epicenter. Learning from the Michoacan earthquake, it has been recognized that urban areas located rather distantly from earthquake sources may not be completely safe from the far-field effects of earth tremors. -

Documentation for the 2007 Update of the National Seismic Hazard Maps

Documentation for the Southeast Asia Seismic Hazard Maps By Mark Petersen, Stephen Harmsen, Charles Mueller, Kathleen Haller, James Dewey, Nicolas Luco, Anthony Crone, David Lidke, and Kenneth Rukstales Administrative Report September 30, 2007 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior 1 DIRK KEMPTHORNE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Mark D. Myers, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia 2007 Revised and reprinted: 200x For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Suggested citation: Author1, F.N., Author2, Firstname, 2001, Title of the publication: Place of publication (unless it is a corporate entity), Publisher, number or volume, page numbers; information on how to obtain if it’s not from the group above. Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted material contained within this report. 2 Contents Overview of Project............................................................................................................................. 5 Project Activities in Thailand........................................................................................................ -

Re-Evaluation of the Activity of the Thoen Fault in the Lampang Basin, Northern Thailand, Based on Geomorphology and Geochronology

Earth Planets Space, 63, 975–990, 2011 Re-evaluation of the activity of the Thoen Fault in the Lampang Basin, northern Thailand, based on geomorphology and geochronology Weerachat Wiwegwin1, Yuichi Sugiyama2, Ken-ichiro Hisada1, and Punya Charusiri3 1Graduate School of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-8572, Japan 2Active Fault and Earthquake Research Center, National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST) 7, 1-1-1 Higashi, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-8567, Japan 3Earthquake and Tectonic Geology Research Unit (EATGRU), c/o Department of Geology, Faculty of Science, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok 10330, Thailand (Received September 7, 2010; Revised February 21, 2011; Accepted June 1, 2011; Online published January 26, 2012) We applied remote sensing techniques and geomorphic index analysis to a study of the NE-SW-striking Thoen Fault, Lampang Basin, northern Thailand. Morphotectonic landforms, formed by normal faulting in the basin, include fault scarps, triangular facets, wine-glass canyons, and a linear mountain front. Along the Thoen Fault, the stream length gradient index records steeper slopes near the mountain front; the index values are possibly related to a normal fault system. Moreover, we obtained low values of the ratio of the valley floor width to valley height (0.44–2.75), and of mountain-front sinuosity (1.11–1.82) along various segments of the fault. These geomorphic indices suggest tectonic activity involving dip-slip displacement on faults. Although the geomorphology and geomorphic indices in the study area indicate active normal faulting, sedimentary units exposed in a trench at Ban Don Fai show no evidence of recent fault movement. -

Tsunamigenic Earthquakes

Fifteen Years of (Major to Great) Tsunamigenic Earthquakes F Romano, S Lorito, and A Piatanesi, Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia, Roma, Italy T Lay, Earth and Planetary Sciences Department, University of California Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA, United States © 2020 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Tsunamis, Seismically Induced 1 Fifteen Years of Major to Great Tsunamigenic Earthquakes 3 The Study of Tsunamigenic Earthquakes 3 Megathrust Tsunamigenic Earthquakes 4 The Sunda 2004–10 Sequence in the Indian Ocean 4 Peru 2007 5 Maule 2010 5 Tohoku 2011 5 Santa Cruz 2013 6 Iquique 2014 6 Illapel 2015 6 Tsunamigenic Doublets 7 Kurils 2006–07 7 Samoa 2009 7 Tsunami Earthquakes 7 Java 2006 8 Mentawai 2010 8 Recent Special Cases 8 Sumatra 2012 8 Solomon 2007 8 Haida Gwaii 2012 9 Kaikoura 2016 9 Mexico 2017 9 Palu 2018 9 Conclusions 10 References 10 Further Reading 12 Tsunamis, Seismically Induced Tsunamis are a series of long gravity waves generated by the displacement of a significant volume of water that propagating in the sea, under the action of the gravity force, returns in its original equilibrium position. Differently from the common wind waves, tsunamis are characterized by large wavelengths (ranging from tens to hundreds of km) and long periods (ranging from minutes to hours). Several natural phenomena such as earthquakes, landslides, volcanic eruptions, the rapid change of atmospheric pressure (meteotsunami), or asteroids impacts can be the source of a tsunami; among these, the most frequent is represented by the earthquakes. Most of the very tsunamigenic earthquakes occur nearby the Earth convergent boundaries (Fig. -

Waves of Destruction in the East Indies: the Wichmann Catalogue of Earthquakes and Tsunami in the Indonesian Region from 1538 to 1877

Downloaded from http://sp.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on May 24, 2016 Waves of destruction in the East Indies: the Wichmann catalogue of earthquakes and tsunami in the Indonesian region from 1538 to 1877 RON HARRIS1* & JONATHAN MAJOR1,2 1Department of Geological Sciences, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT 84602–4606, USA 2Present address: Bureau of Economic Geology, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78758, USA *Corresponding author (e-mail: [email protected]) Abstract: The two volumes of Arthur Wichmann’s Die Erdbeben Des Indischen Archipels [The Earthquakes of the Indian Archipelago] (1918 and 1922) document 61 regional earthquakes and 36 tsunamis between 1538 and 1877 in the Indonesian region. The largest and best documented are the events of 1770 and 1859 in the Molucca Sea region, of 1629, 1774 and 1852 in the Banda Sea region, the 1820 event in Makassar, the 1857 event in Dili, Timor, the 1815 event in Bali and Lom- bok, the events of 1699, 1771, 1780, 1815, 1848 and 1852 in Java, and the events of 1797, 1818, 1833 and 1861 in Sumatra. Most of these events caused damage over a broad region, and are asso- ciated with years of temporal and spatial clustering of earthquakes. The earthquakes left many cit- ies in ‘rubble heaps’. Some events spawned tsunamis with run-up heights .15 m that swept many coastal villages away. 2004 marked the recurrence of some of these events in western Indonesia. However, there has not been a major shallow earthquake (M ≥ 8) in Java and eastern Indonesia for the past 160 years. -

Tectonic Setting Seismic Hazard Epicentral Region Depth Profile

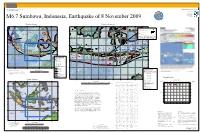

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR EARTHQUAKE SUMMARY MAP XXX U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Prepared in cooperation with the Global Seismographic Network e g M6.7 Sumbawa, Indoned sia, Earthquake of 8 November 2009 i R u a l a P - Tectonic Setting u Epicentral Region V I E T N A M P h i l i p p i n e h 100° 110° F a u l t 120° 130° s 110° 112° 114° 116° 118° 120° 122° 124° 126° 128° C A M B O D I A u S u m a t r a y P Palu K Balikpapan H Kalimantan 2000 1963 1923 P H I L I P P I N E S I L P h i l i p p i n e I A N D A M A N P Barat Kalimantan Timur Sumbawa Region P B a s i n Sulawesi Tengah Gulf I 1998 S E A N 10° 10° of S O U T H E 08 November 2009 8:41:44 UTC Thailand T 2° 2° C H I N A R Palangkaraya 1965 N E Kalimantan Tengah A N W H 1919 S E A A G C 8.315° S., 118.697° E. L U A O H P R Kalimantan Depth 18.3 km T Selatan M19w38 = 6.7 (1U94S8GS) SUNDA PLATE Sulawesi Bandjermasin Maluku Selatan B R U N E I 15 km (10 miles) 1N9N50W of Raba, Sumbawa, Indonesia M 310 km (1A9m0b moniles) ENE of Mataram, Lombok, Indonesia A C e l e b e s L Kendari 2001 A B a s i n 330 km (205 miles) W of Ende, Flores, Indonesia Y S u m a t r a F a u l t 4° 4° S A I N D O N E S I A 2004 I 1335 km (830 miles) E of JAKARTA, Java, Indonesia I S A Y A L A M S I N G A P O R E S u 0° m Borneo 0° Makassar 2006 1914 a MOLUCCA 2005 tr a SEA Enggano I N D O N E S IPLATEA BIRD'S HEAD A' 1797 PLATE 6° 6° 1950 1927 AUSTRALIA J a v a 1969 PLATE J A VA S E A 1998 Semarang 1934 1833 1996 1964 1995 BANDA SEA MAOKE Jawa 1966 Greater Sunda Islands B A N D A S E A 1990 1982 I PLATE PLATE -

Original Pdf Version

Rhiana Elizabeth Henry Tectonic History Hildebrand Project 1A December 9th, 2016 North America subducted under Rubia Are there modern analogs for Hildebrand’s model of North America subducting under Rubia? In the Geological Society of America Special Papers “Did Westward Subduction Cause Cretaceous–Tertiary Orogeny in the North American Cordillera?” and “Mesozoic Assembly of the North American Cordillera” by Robert S. Hildebrand, the author argues that the North American continent experienced westward subduction under what he calls a “ribbon continent” known as Rubia around ~124Ma. This ribbon continent is composed of multiple terranes both known to be exotic to North America, and terranes that were previously thought to be part of North America. As the seaway between Rubia and North America closed, Hildebrand postulates that North America was dragged underneath with the oceanic crust. This continental material combined with the fluids from the margin caused great amounts of magmatism in the North American Cordillera. Eventually the continental crust broke due to upward buoyancy. This caused slab failure around 75-60 Ma, followed by a reversal of subduction polarity around 53 Ma, with eastward subduction through the mid- Tertiary (Fig. 1). As a way of checking to see if this hypothesis is plausible, I investigated modern geologic settings that are undergoing similar tectonic events. Although these regions are Figure 1: Hildebrand’s model of subduction of not perfect analogies, they share enough North America and Rubia. From Hildebrand, 2009. 1 Rhiana Elizabeth Henry Tectonic History Hildebrand Project 1A December 9th, 2016 tectonic features that Hildebrand’s model appears somewhat less outlandish. -

Philippine Island Arc System Tectonic Features Inferred from Magnetic Data Analysis

Terr. Atmos. Ocean. Sci., Vol. 26, No. 6, 679-686, December 2015 doi: 10.3319/TAO.2015.05.11.04(TC) Philippine Island Arc System Tectonic Features Inferred from Magnetic Data Analysis Wen-Bin Doo1, *, Shu-Kun Hsu1, 2, and Leo Armada 2 1 Center for Environmental Studies, National Central University, Taoyuan City, Taiwan, R.O.C. 2 Department of Earth Sciences, National Central University, Taoyuan City, Taiwan, R.O.C. Received 18 February 2013, revised 22 November 2013, accepted 11 May 2015 ABSTRACT Running along the middle of the Philippine archipelago from south to north, the Philippine fault zone is one of the world’s major strike-slip faults. Intense volcanism in the archipelago is attributed to the ongoing subduction along the trench systems surrounding it. This study interprets the magnetic data covering the Philippine fault zone and the bounding archi- pelago subduction systems to understand the structural characteristics of the study area. Magnetic data analysis suggests that the Philippine fault is roughly distributed along the boundary of high/low magnetization and separates the different amplitude features of the first order analytic signal. Visayas province is a specific area bounded by the other parts of the Philippine ar- chipelago. Further differentiating the tectonic units, the proto-Southeast Bohol Trench should be the main tectonic boundary between Visayas and Mindanao. A clear NE - SW boundary separates Luzon from Visayas as shown by the variant depths to the top of the magnetic basement. This boundary could suggest the different tectonic characteristics of the two regions. Key words: Philippine fault, Philippine archipelago, Magnetic data, Tectonic Citation: Doo, W. -

Java and Sumatra Segments of the Sunda Trench: Geomorphology and Geophysical Settings Analysed and Visualized by GMT Polina Lemenkova

Java and Sumatra Segments of the Sunda Trench: Geomorphology and Geophysical Settings Analysed and Visualized by GMT Polina Lemenkova To cite this version: Polina Lemenkova. Java and Sumatra Segments of the Sunda Trench: Geomorphology and Geophys- ical Settings Analysed and Visualized by GMT. Glasnik Srpskog Geografskog Drustva, 2021, 100 (2), pp.1-23. 10.2298/GSGD2002001L. hal-03093633 HAL Id: hal-03093633 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03093633 Submitted on 4 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License ГЛАСНИК Српског географског друштва 100(2) 1 – 23 BULLETIN OF THE SERBIAN GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY 2020 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------ --------------------------------------- Original scientific paper UDC 551.4(267) https://doi.org/10.2298/GSGD2002001L Received: October 07, 2020 Corrected: November 27, 2020 Accepted: December 09, 2020 Polina Lemenkova1* * Schmidt Institute of Physics of the Earth, Russian Academy of Sciences, Department of Natural Disasters, Anthropogenic Hazards and Seismicity of the Earth, Laboratory of Regional Geophysics and Natural Disasters, Moscow, Russian Federation JAVA AND SUMATRA SEGMENTS OF THE SUNDA TRENCH: GEOMORPHOLOGY AND GEOPHYSICAL SETTINGS ANALYSED AND VISUALIZED BY GMT Abstract: The paper discusses the geomorphology of the Sunda Trench, an oceanic trench located in the eastern Indian Ocean along the Sumatra and Java Islands of the Indonesian archipelago. -

Using a Genetic Algorithm to Estimate the Details of Earthquake Slip Distributions from Point Surface Displacements

Edinburgh Research Explorer Using a genetic algorithm to estimate the details of earthquake slip distributions from point surface displacements Citation for published version: Lindsay, A, McCloskey, J & Bhloscaidh, MN 2016, 'Using a genetic algorithm to estimate the details of earthquake slip distributions from point surface displacements', Journal of Geophysical Research. Solid Earth, vol. 121, no. 3, pp. 1796-1820. https://doi.org/10.1002/2015JB012181 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1002/2015JB012181 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Journal of Geophysical Research. Solid Earth General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 06. Oct. 2021 PUBLICATIONS Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth RESEARCH ARTICLE Using a genetic algorithm to estimate the details 10.1002/2015JB012181 of earthquake slip distributions -

Regional Seismic Hazard Posed by the Mentawai Segment of the Sumatran Megathrust by Kusnowidjaja Megawati and Tso-Chien Pan

Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, Vol. 99, No. 2A, pp. 566–584, April 2009, doi: 10.1785/0120080109 Regional Seismic Hazard Posed by the Mentawai Segment of the Sumatran Megathrust by Kusnowidjaja Megawati and Tso-Chien Pan Abstract Several lines of evidence have indicated that the Mentawai segment of the Sumatran megathrust is very likely to rupture within the next few decades. The present study is to investigate seismic hazard and risk levels at major cities in Sumatra, Java, Singapore, and the Malay Peninsula caused by the potential giant earthquakes. Three scenarios are considered. The first one is an Mw 8.6 earthquake rupturing the 280 km segment that has been locked since 1797; in the second scenario, rupture oc- curs along a 600 km segment covering the combined rupture areas of the 1797 and 1833 historical events, producing an Mw 9.0 earthquake; and the third scenario has the same rupture area as the second scenario but with doubled slip amplitude, resulting in an Mw 9.2 earthquake. Simulation results indicate that ground motions produced by the hypothetical scenarios are strong enough to cause yielding to medium- and high- rise buildings in many major cities in Sumatra. It is vital to ensure that the overall strength, stiffness, and integrity of the structures are maintained throughout the entire duration of shaking. However, the ductile detailing in current practice is formulated based on an assumption that ground motions would last from 20 to 40 sec. This has not been tested for longer durations of 3–5 min, expected from giant earthquakes.