Economic Evaluation of the Upland Experiment (Bodmin Moor Project and Bowland Initiative)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hallworthy Stockyard

SOUTH WEST LIMOUSIN SPRING SALE Exeter Livestock Centre Friday 23rd April 2021 ** Please note, due to Covid there will be no show this year & the sale will be held under strict Covid rules ** Sale to include 9 Bulls, 7 Cows With Calves at Foot, 1 Recipient Dam carrying an embryo & 8 Heifers Sale – Approx. 12 Noon British Limousin Cattle Society Breeders’ Sale On behalf of Members of the South Western Limousin Auctioneer: Mark Davis 07773 371774 Exeter Livestock Centre, Exeter, Devon EX2 8FD Office: 01392 251261 – [email protected] Breeders’ Club British Limousin Cattle Society Breeders’ Sale held under BLCS Auction Rules and subject to the recommended Terms & Conditions of Sale of the National Beef Association. ENTRY CLOSING DATE No substitution Bulls/animals will be accepted other than those in the catalogue. Any other Bulls/animals, not in the catalogue will go at the end, and be for Sale only. ENTRY FEES £15 + VAT per animal or per Cow & Calf payable to Kivells The South Western Limousin Cattle Breeders’ Club welcomes entries from Breeders from other Clubs. All vendors need to pay the £15 subscription to the South West Limousin Cattle Breeders Club. Failure to do so may lead to non-acceptance of entry. The original pedigree certificate must accompany the entry. TIMES Viewing and Inspection prior to the sale. TRANSFER FEE Pedigree certificates will be transferred to purchasers free of charge by the British Limousin Cattle Society following the sale. For any Pedigree or Membership enquiries, please contact British Limousin Cattle Society Tel: 02476 696500 ORDER OF SALE Bulls sold in catalogue order. -

DIRECTIONS to WOOLGARDEN from the A30 WESTBOUND (M5/Exeter)

DIRECTIONS TO WOOLGARDEN FROM THE A30 WESTBOUND (M5/Exeter) About 2 miles beyond Launceston, take the A395 towards Camelford and Bude. After 10 minutes you come to Hallworthy, turn left here, opposite the garage and just before the Wilsey Down pub: - Continue straight on for 2 miles. The postcode centre (PL15 8PT) is near a T-junction with a triangular patch of grass in the middle. Continue round to the left at this point: - Continue for about a quarter mile down a small dip and up again. You will the come to a cream- coloured house and bungalow on the right. The track to Woolgarden is immediately after this on the same side, drive a short distance down the track and you have arrived! DIRECTIONS TO WOOLGARDEN FROM CORNWALL AND PLYMOUTH From Bodmin, Mid and West Cornwall: Follow the A30 towards Launceston. Exit the A30 at Five Lanes, as you descend from Bodmin Moor, then follow the directions below. From Plymouth & SE Cornwall: Follow the A38 to Saltash then the A388 through Callington, then soon afterwards fork left onto the B2357, signposted Bodmin. (Or from Liskeard direction, take the B3254 towards Launceston, then turn left onto the B3257 at Congdons Shop.) Then at Plusha join the A30 towards Bodmin and then come off again the first exit, Five Lanes, then follow the directions below. In the centre of Five Lanes (Kings Head pub), follow signs to Altarnun and Camelford: - Continue straight on, through Altarnun, for about 1.5 miles, then turn left at the junction, signposted Camelford. Soon afterward, keep the Rinsing Sun pub on your left:- After a mile, turn right at the crossroads, signposted St Clether and Hallworthy: - And after another mile, go straight across the crossroad: - A half mile further on, you will pass Tregonger farm on your right, and then see a cream coloured bungalow on your left. -

Hallworthy Market Report

HALLWORTHY MARKET REPORT THURSDAY 5th NOVEMBER 2020 EVERY THURSDAY Gates Open 6.30am SALE TIMES 09:45 am Draft Ewes followed by Prime, Store Hoggs & Breeding Sheep 10:45am Tested & Untested Prime & OTM Cattle 11:00 am Store Cattle & Stirk Hallworthy Stockyard, Hallworthy, Camelford, Cornwall, PL32 9SH Tel: 01840 261261 Fax: 01840 261684 Website: www.kivells.com Email: [email protected] SHEEP AUCTIONEER STEVE PROUSE 07767 895366 136 DRAFT EWES A flying trade up around £8 to £9 a head, top being £109 from Shaun Ellis, North Petherwin. Mules topped at £80 from Graham Tambly of Morval. Hill bred Ewes to £69. 353 FAT LAMBS Weight Top Average Good entry met a faster trade for all weights, Per Head Per Per Per and a lot more could have been sold as Kilo Head Kilo buyer’s orders were left unfilled. Several pens 39.1-45.5 97.50 222 88.60 206 over 214p to a top of 222p for two pens of 45.6-52 100 214 96 201.9 44kgs £97.50, from Mr P Mitchell of Par. Overall 100 222 93 206 Followed by Shaun Ellis of North Petherwin who realised 218p for a pen of 40kgs Charollais. Top per head on the day was £100 from Robert Reddaway of Honeychurch, North Tamerton. 154 STORE LAMBS Small entry but a flying trade, top being £85 from Robin and Harry Tamblyn of Morval Barton. 340 BREEDING EWES A strong trade met by the breeders, strongest trade on the day met by a bunch of Cheviot Ewe Lambs from Victor Rickard of New House, St Clether, with a top of £122, and other pens at £100, and £98. -

Hallworthy Market Report

HALLWORTHY MARKET REPORT THURSDAY 1st OCTOBER 2020 EVERY THURSDAY Gates Open 6.30am SALE TIMES 09:45 am Draft Ewes followed by Prime, Store Hoggs & Breeding Sheep 10:45am Tested & Untested Prime & OTM Cattle 11:00 am Store Cattle & Stirk Hallworthy Stockyard, Hallworthy, Camelford, Cornwall, PL32 9SH Tel: 01840 261261 Fax: 01840 261684 Website: www.kivells.com Email: [email protected] SHEEP AUCTIONEER STEVE PROUSE 07767 895366 342 DRAFT EWES Another good entry very much in demand, top being £100 from Steve Lyne of Bodmin. 9 other pens over £85. 174 FAT LAMBS Smaller entry met an easier trade inline with the rest of the country, the well fleshed lambs selling from 200p to a top of 204p for a Weight Top Average pen of 41kgs, £83.50 for Mr Per Per Kilo Per Per Kilo Toby Dance of St Ervan. Top Head Head 39.1-45.5 87.50 204 81.50 192 per head was £97 for two 45.6-52 97 201 92 192.2 pens from Miss M H 52+ 93 172 93 172.2 Goodenough, Davidstow. Overall 97 204 89 192 742 STORE LAMBS Larger entry again in keen demand, the large framed lambs still realising £77, to a top of £83 from Miss M Goodenough of Davidstow. STORE CATTLE AUCTIONEER RICHARD DENNIS STORE CATTLE A cracking day at Hallworthy with over 400 Cattle through the rings. 330 Store Cattle were headed up this week by EJ & BA Masters of Mount with a superb pair of South Devon x Limousin Steers with depth and definition to £1145. -

Wind Turbines East Cornwall

Eastern operational turbines Planning ref. no. Description Capacity (KW) Scale Postcode PA12/02907 St Breock Wind Farm, Wadebridge (5 X 2.5MW) 12500 Large PL27 6EX E1/2008/00638 Dell Farm, Delabole (4 X 2.25MW) 9000 Large PL33 9BZ E1/90/2595 Cold Northcott Farm, St Clether (23 x 280kw) 6600 Large PL15 8PR E1/98/1286 Bears Down (9 x 600 kw) (see also Central) 5400 Large PL27 7TA E1/2004/02831 Crimp, Morwenstow (3 x 1.3 MW) 3900 Large EX23 9PB E2/08/00329/FUL Redland Higher Down, Pensilva, Liskeard 1300 Large PL14 5RG E1/2008/01702 Land NNE of Otterham Down Farm, Marshgate, Camelford 800 Large PL32 9SW PA12/05289 Ivleaf Farm, Ivyleaf Hill, Bude 660 Large EX23 9LD PA13/08865 Land east of Dilland Farm, Whitstone 500 Industrial EX22 6TD PA12/11125 Bennacott Farm, Boyton, Launceston 500 Industrial PL15 8NR PA12/02928 Menwenicke Barton, Launceston 500 Industrial PL15 8PF PA12/01671 Storm, Pennygillam Industrial Estate, Launceston 500 Industrial PL15 7ED PA12/12067 Land east of Hurdon Road, Launceston 500 Industrial PL15 9DA PA13/03342 Trethorne Leisure Park, Kennards House 500 Industrial PL15 8QE PA12/09666 Land south of Papillion, South Petherwin 500 Industrial PL15 7EZ PA12/00649 Trevozah Cross, South Petherwin 500 Industrial PL15 9LT PA13/03604 Land north of Treguddick Farm, South Petherwin 500 Industrial PL15 7JN PA13/07962 Land northwest of Bottonett Farm, Trebullett, Launceston 500 Industrial PL15 9QF PA12/09171 Blackaton, Lewannick, Launceston 500 Industrial PL15 7QS PA12/04542 Oak House, Trethawle, Horningtops, Liskeard 500 Industrial -

CORNWALL Extracted from the Database of the Milestone Society

Entries in red - require a photograph CORNWALL Extracted from the database of the Milestone Society National ID Grid Reference Road No Parish Location Position CW_BFST16 SS 26245 16619 A39 MORWENSTOW Woolley, just S of Bradworthy turn low down on verge between two turns of staggered crossroads CW_BFST17 SS 25545 15308 A39 MORWENSTOW Crimp just S of staggered crossroads, against a low Cornish hedge CW_BFST18 SS 25687 13762 A39 KILKHAMPTON N of Stursdon Cross set back against Cornish hedge CW_BFST19 SS 26016 12222 A39 KILKHAMPTON Taylors Cross, N of Kilkhampton in lay-by in front of bungalow CW_BFST20 SS 25072 10944 A39 KILKHAMPTON just S of 30mph sign in bank, in front of modern house CW_BFST21 SS 24287 09609 A39 KILKHAMPTON Barnacott, lay-by (the old road) leaning to left at 45 degrees CW_BFST22 SS 23641 08203 UC road STRATTON Bush, cutting on old road over Hunthill set into bank on climb CW_BLBM02 SX 10301 70462 A30 CARDINHAM Cardinham Downs, Blisland jct, eastbound carriageway on the verge CW_BMBL02 SX 09143 69785 UC road HELLAND Racecourse Downs, S of Norton Cottage drive on opp side on bank CW_BMBL03 SX 08838 71505 UC road HELLAND Coldrenick, on bank in front of ditch difficult to read, no paint CW_BMBL04 SX 08963 72960 UC road BLISLAND opp. Tresarrett hamlet sign against bank. Covered in ivy (2003) CW_BMCM03 SX 04657 70474 B3266 EGLOSHAYLE 100m N of Higher Lodge on bend, in bank CW_BMCM04 SX 05520 71655 B3266 ST MABYN Hellandbridge turning on the verge by sign CW_BMCM06 SX 06595 74538 B3266 ST TUDY 210 m SW of Bravery on the verge CW_BMCM06b SX 06478 74707 UC road ST TUDY Tresquare, 220m W of Bravery, on climb, S of bend and T junction on the verge CW_BMCM07 SX 0727 7592 B3266 ST TUDY on crossroads near Tregooden; 400m NE of Tregooden opp. -

Hallworthy Market Report

HALLWORTHY MARKET REPORT THURSDAY 3rd SEPTEMBER 2020 EVERY THURSDAY Gates Open 6.30am SALE TIMES 09:45 am Draft Ewes followed by Prime, Store Hoggs & Breeding Sheep 10:45am Tested & Untested Prime & OTM Cattle 11:00 am Store Cattle & Stirk Hallworthy Stockyard, Hallworthy, Camelford, Cornwall, PL32 9SH Tel: 01840 261261 Fax: 01840 261684 Website: www.kivells.com Email: [email protected] SHEEP AUCTIONEER STEVE PROUSE 07767 895366 150 DRAFT EWES A very strong trade through out top of the day was £110 from C Statton of Fennel, Launceston, followed by Mervin Gimblett of Treneglos, who realised £96 with his continental x. Mr A C Brewer of Boscastle topped the Suffolk x at £92, Weight Top Average also Mules topped at £84. Per Head Per Kilo Per Head Per Kilo 435 FAT LAMBS 32.1-39 80 211 77 202 Much larger entry again met a faster 39.1-45.5 98 218 90 208.7 trade and still a lot more could have 45.6-52 106 221 101 212.3 been sold, overall average on the day 52+ 105 172 104.50 170 was 208.6ppkilo. The smart export Overall 106 221 96.50 208.6 lambs ranging from 218 to a top of 221p for a pen of Texel 48kgs £106 from C A Statton of Fennel, Launceston. Mrs D Treffry of Fowey who realised 218p for her two pens of 45kgs £98. Several pens over £100 to a top of £106 from three vendors. 343 STORE LAMBS A flying trade for all breeds and sizes and with hill bred in the overall average of £73.40. -

Launceston to Bodmin Parkway 10 Via Camelford | Delabole | Port Isaac | Polzeath | Wadebridge | Bodmin

Launceston to Bodmin Parkway 10 via Camelford | Delabole | Port Isaac | Polzeath | Wadebridge | Bodmin Mondays to Saturdays except bank holidays 10S Launceston Westgate St 0710 0740 0925 1125 1325 1325 1515 1535 1740 Launceston College 1525 Tregadillett Primary School 0718 0748 0933 1133 1333 1333 1532 1548 1753 Trethorne Leisure Farm opp 0720 0750 0935 1135 1335 1335 1534 1550 1755 Pipers Pool opp Bus Shelter 0724 0754 0939 1139 1339 1339 1538 1554 1758 Badgall 1545 Tregeare 1547 24 Hallworthy Old Post Office 0731 0801 0946 1146 1346 1346 1600 1601 1601 1805 Trelash 1607 Warbstow Cross 1610 Canworthy Water Chapel 1615 Davidstow opp Church Hall 0735 0805 0950 1150 1350 1350 1605 1605 1808 Arthurian Centre 0740 Delabole Post Office 0745 0745 Weatdowns The Skerries 0750 0750 St Teath Post Office 0756 0756 Helstone Bus Shelter 0800 0800 Camelford Church 0811 0956 1156 1356 1356 1611 1611 1814 Camelford Clease Road 0703 0703 0813 0958 1158 1358 1358 1613 1613 1816 Sir James Smith School 0705 0705 0810 0810 0815 1000 1200 1400 1400 1435 1615 1615 1817 Delabole Post Office 0715 0715 0825 0825 1010 1210 1410 1410 1445 1625 1625 1825 Delabole West Downs Road 0717 0717 0827 0827 1012 1212 1412 1412 1447 1627 1627 1827 Pendoggett Cornish Arms 0726 0726 0836 0836 1021 1221 1421 1421 1456 1636 1636 1836 Port Isaac The Pea Pod 0735 0735 0845 0845 1030 1230 1430 1505 1645 1645 1845 St Endellion Church 0743 0743 0853 0853 1038 1238 1425 1438 1513 1653 1653 1853 Polzeath opp Beach 0755 0755 0755 0905 0905 1050 1250 1437 1450 1705 1705 1905 Rock opp Clock -

Gardens Guide

Gardens of Cornwall map inside 2015 & 2016 Cornwall gardens guide www.visitcornwall.com Gardens Of Cornwall Antony Woodland Garden Eden Project Guide dogs only. Approximately 100 acres of woodland Described as the Eighth Wonder of the World, the garden adjoining the Lynher Estuary. National Eden Project is a spectacular global garden with collection of camellia japonica, numerous wild over a million plants from around the World in flowers and birds in a glorious setting. two climatic Biomes, featuring the largest rainforest Woodland Garden Office, Antony Estate, Torpoint PL11 3AB in captivity and stunning outdoor gardens. Enquiries 01752 814355 Bodelva, St Austell PL24 2SG Email [email protected] Enquiries 01726 811911 Web www.antonywoodlandgarden.com Email [email protected] Open 1 Mar–31 Oct, Tue-Thurs, Sat & Sun, 11am-5.30pm Web www.edenproject.com Admissions Adults: £5, Children under 5: free, Children under Open All year, closed Christmas Day and Mon/Tues 5 Jan-3 Feb 16: free, Pre-Arranged Groups: £5pp, Season Ticket: £25 2015 (inclusive). Please see website for details. Admission Adults: £23.50, Seniors: £18.50, Children under 5: free, Children 6-16: £13.50, Family Ticket: £68, Pre-Arranged Groups: £14.50 (adult). Up to 15% off when you book online at 1 H5 7 E5 www.edenproject.com Boconnoc Enys Gardens Restaurant - pre-book only coach parking by arrangement only Picturesque landscape with 20 acres of Within the 30 acre gardens lie the open meadow, woodland garden with pinetum and collection Parc Lye, where the Spring show of bluebells is of magnolias surrounded by magnificent trees. -

Hallworthy Market Report

HALLWORTHY MARKET REPORT THURSDAY 21st JANUARY 2021 EVERY THURSDAY Gates Open 6.30am SALE TIMES 09:45 am Draft Ewes followed by Prime, Store Hoggs & Breeding Sheep 10:45am Tested & Untested Prime & OTM Cattle 11:00 am Store Cattle & Stirk Hallworthy Stockyard, Hallworthy, Camelford, Cornwall, PL32 9SH Tel: 01840 261261 Fax: 01840 261684 Website: www.kivells.com Email: [email protected] SHEEP AUCTIONEER STEVE PROUSE 07767 895366 194 DRAFT EWES Good entry met a slightly easier trade but the heavy Ewes still realising £95 and 8 pens over £100 to a top of £106 from Richard Parsons of Venn Down, Minster. 331 FAT HOGGS Weight Top Average Another good entry, very much sought Per Head Per Kilo Per Head Per Kilo after, overall average of 246.8p. The 39.1-45.5 113.50 258 106.50 247.7 well fleshed Hoggs saw several pens 45.6-52 120 261 114.50 242.2 over 255p to a top of 261p for a pen of 52+ 125 231 119.30 217.3 46kgs £120, from Colin Baker Overall 125 261 111.50 246.8 Nanswhyden, St Columb, followed by Mervin Gimblett of Churchtown who realised 258p for a pen of 44kgs £113.50. Several pens of heavies over £118 to a top of £125 from C A Statton of Badgall. 365 STORE LAMBS Similar entry met a sharper trade and a lot more could have been sold, pen after pen realised £90 plus to a top on the day £108 sold by Colin Baker of Nanswhyden, St Columb who also sold other pens at £106 and £100. -

Hallworthy Hallworthy Parkenhead, Trevone, Padstow, PL28 8QH Beach 0.6 Miles Padstow 1.8 Miles Wadebridge 8.3 Miles

Hallworthy Hallworthy Parkenhead, Trevone, Padstow, PL28 8QH Beach 0.6 miles Padstow 1.8 miles Wadebridge 8.3 miles • Just over half a mile to the beach • Three double bedrooms • Two reception rooms • Family bathroom • Garden • Garage & parking • Close to local amenities Offers in excess of £525,000 SITUATION The property is located at the end of a no through road, a short distance from the village centre and beaches. Trevone has long since been one of the most popular bays south of Padstow, renowned for its delightful beaches and scenic walks. Nestling between Padstow and Harlyn there are two entirely different beaches, one sandy for surfing enthusiasts and families while the other is a picturesque rocky beach perfect for exploring rock pools and swimming in the tidal sea pool. The village offers a range of local facilities including a Substantial coastal bungalow in the sought after beach store/farm shop and local public house. location of Trevone The picturesque fishing harbour of Padstow is just 1.8 miles away with the internationally renowned home of Rick Stein's seafood restaurants. Surrounded by an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty the harbour boasts a myriad of quaint narrow streets arranged around the working harbour, together with a wide variety of shops, restaurants and boutiques. The immediate area offers other fine beaches, including Treyarnon, Harlyn and Constantine, together with an extensive selection of water sports. There is a championship golf course at Trevose and the Camel Trail links with Wadebridge and is popular with cyclists and walkers. The town of Wadebridge is approximately 8.3 miles away offering educational facilities to Sixth Form level and a wide range of supermarkets, shops and amenities. -

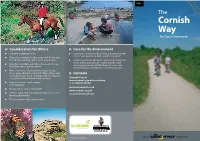

The Cornish Way an Forth Kernewek

Map The Cornish Way An Forth Kernewek Consideration for Others Care for the Environment • Follow the Highway Code. • Leave your car at home if possible. Can you reach the start of your journey by bike or public transport? • Please be courteous to other users, and do not give the ‘The Cornish Way’ and its users a bad name. • Follow the Countryside Code. In particular: take litter home with you; keep to the routes provided and • Give way to walkers and, where necessary, horses. shut any gates; leave wildlife, livestock, crops and Slow down when passing them! machinery alone; and make no unnecessary noise. • Warn other users of your presence, particularly when approaching from behind. Warn a horse with Contacts some distance to spare - ringing a bell or calling out a greeting will avoid frightening the horse. Cornwall Council www.cornwall.gov.uk/cornishway • Keep to the trails, roads, byways or tel: 0300 1234 202 and bridleways. www.nationalrail.co.uk • Do not ride or cycle on footpaths. www.sustrans.org.uk • Respect other land management industries such as www.visitcornwall.com farming and forestry. • Please park your bike considerately. © Cornwall Council 2012 Part of cycle network Lower Tamar Lake and Cycle Trail Bude Stratton Marhamchurch Widemouth Bay Devon Coast to Coast Trail Millbrook Week St Mary Wainhouse Corner Warbstow Trelash proposed Hallworthy Camel - Tarka Link Launceston Lower Tamar Lake and Cycle Trail Camelford National Cycle Network 2 3 32 Route Number 0 5 10 20 Bude Stratton Kilometres Regional Cycle Network 67 Marhamchurch