Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saudi Arabia Under King Faisal

SAUDI ARABIA UNDER KING FAISAL ABSTRACT || T^EsIs SubiviiTTEd FOR TIIE DEqREE of ' * ISLAMIC STUDIES ' ^ O^ilal Ahmad OZuttp UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF DR. ABDUL ALI READER DEPARTMENT OF ISLAMIC STUDIES ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 1997 /•, •^iX ,:Q. ABSTRACT It is a well-known fact of history that ever since the assassination of capital Uthman in 656 A.D. the Political importance of Central Arabia, the cradle of Islam , including its two holiest cities Mecca and Medina, paled into in insignificance. The fourth Rashidi Calif 'Ali bin Abi Talib had already left Medina and made Kufa in Iraq his new capital not only because it was the main base of his power, but also because the weight of the far-flung expanding Islamic Empire had shifted its centre of gravity to the north. From that time onwards even Mecca and Medina came into the news only once annually on the occasion of the Haj. It was for similar reasons that the 'Umayyads 661-750 A.D. ruled form Damascus in Syria, while the Abbasids (750- 1258 A.D ) made Baghdad in Iraq their capital. However , after a long gap of inertia, Central Arabia again came into the limelight of the Muslim world with the rise of the Wahhabi movement launched jointly by the religious reformer Muhammad ibn Abd al Wahhab and his ally Muhammad bin saud, a chieftain of the town of Dar'iyah situated between *Uyayana and Riyadh in the fertile Wadi Hanifa. There can be no denying the fact that the early rulers of the Saudi family succeeded in bringing about political stability in strife-torn Central Arabia by fusing together the numerous war-like Bedouin tribes and the settled communities into a political entity under the banner of standard, Unitarian Islam as revived and preached by Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab. -

Slavery in the Gulf in the First Half of the 20Th Century

Slavery in the Gulf in the First Half of the 20th Century A Study Based on Records from the British Archives 1 2 JERZY ZDANOWSKI Slavery in the Gulf in the First Half of the 20th Century A Study Based on Records from the British Archives WARSZAWA 2008 3 Grant 1 H016 048 30 of the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education The documents reproduced by the permission of the British Library Copyright Jerzy Zdanowski 2008 This edition is prepared, set and published by Wydawnictwo Naukowe ASKON Sp. z o.o. ul. Stawki 3/1, 00193 Warszawa tel./fax: (+48 22) 635 99 37 www.askon.waw.pl [email protected] ISBN 9788374520300 4 Contents List of Photos, Maps and Tables.......................................................................... 7 Glossary ..................................................................................................... 9 Preface and acknowledgments ...................................................................11 Introduction: Slaves, pearls and the British in the Persian Gulf at the turn of the 20th century ................................................................................ 16 Chapter I: Manumission certificates ........................................................... 45 1. The number of statements ................................................................. 45 2. Procedures ...................................................................................... 55 3. Eligibility .......................................................................................... 70 4. Value of the -

+ Qatif City Profile

Future Saudi Cities Programme Disclaimer City Profiles Series: Qatif The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of © 2019. Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the King Fahd National Library Cataloging-in-publication Data United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Views expressed in Qatif City Profile./ Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the Ministry Riyadh, 2019 of Municipal and Rural Affairs, the United Nations Human ..p ; ..cm Settlements Programme, the United Nations or its Member States.Excerpts may be reproduced without authorisation, on ISBN: 978-603-8279-02-1 condition that the source is indicated. 1-Al-Qatif (Saudi Arabia) - Description and travel ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 2- Eastern region (Saudi Arabia)- History City Profiles Series Editors: I-Title Herman Pienaar 915.3135 dc 1440/8075 Salvatore Fundarò Costanza La Mantia L.D. no. 1440/8075 ISBN: 978-603-8279-02-1 Contributing Authors: Luis Angel Del Llano Gilio (urban planning & design) © 2019. Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs and United Costanza La Mantia (content editor) Nations Human Settlements Programme Rama Nimri (regional planning) All rights reserved. Anne Klen-Amin (legal & governance) Samuel Njuguna (legal & governance) Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs Dr. Faisal Bin Sulaiman (legal & governance) P.O. Box : 935 - King Fahd, Riyadh, 11136 Giuseppe Tesoriere (economy & finance) Tel: 00966114569999 Elizabeth Glass (economy & finance) www.momra.gov.sa Mario Tavera (GIS) Solomon Karani (GIS) United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) Layout Design: P.O. -

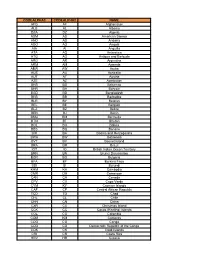

SN V.I.N. / Voter's Name Voter's Address Sex Birthdate / Biometrics 1 ABAD, AMADEO MARCELO CO AUJAN BEVERAGES CO

SN V.I.N. / Voter's Name Voter's Address Sex Birthdate / Biometrics 1 ABAD, AMADEO MARCELO CO AUJAN BEVERAGES CO. P.O. BOX 15882 2ND M 18-Feb-1982 INDUSTRIAL CITY DAMMAM KSA 2 ABAD, EMILIANO MALLARI DAMMAM M 15-Feb-1974 3 ABAD, RENATO ANGELES ABU HADRIYAH 91 M 2-Apr-1964 4 ABARQUEZ, GREL GO JUBAIL M 29-Aug-1973 5 ABAYA, REYVELSON DELA PENA PO BOX 36908 JUBAIL INDUSTRIAL CITY 31961 M 22-Feb-1988 6 ABDULA, ABDURAJIM ABDURAHIM MMG CAMP SITE, DAMMAM M 21-Sep-1959 7 ABIRIN, PARMAISULI LALING AL AHSA KSA F 18-Mar-1971 8 ABISO, ALEXANDER AQUERY JUBAIL-KSA M 16-Feb-1974 9 ABRENCILLO, SHANE BERROYA DAMMAM F 20-Apr-1988 10 ABREU, WILFREDO FABIANA AL THUQBAH, KHOBAR M 26-Nov-1958 11 ACQUIOT, ALEXANDRA ENRIQUEZ AL BADIAH, DAMMAM F 2-Jun-1986 12 ADO, DOMINGO OLEA MMG P.O. BOX 11 DAMMAM 31411 M 11-Dec-1955 13 ADRIANO, WILFREDO ENRIQUEZ P.O. 20074, ALKHOBAR M 7-May-1962 14 AGAA, ANDRES VILLANUEVA AL JUBAIL M 4-Feb-1976 15 AGARRADO, REUEL ANDRES ESPINOSA P.O. BOX 35579 JUBAIL INDUSTRIAL CITY 31961 M 2-Mar-1953 K.S.A. 16 AGARRADO, SALVACION VERBA P.O. BOX 35579 JUBAIL INDUSTRIAL CITY 31961 F 12-Jul-1957 17 AGCAOILI, JOSEPH VALENZUELA JUBAIL M 23-Jun-1982 18 AGRAVANTE, LUISITU COGONON SK ENGINEERING AND CONSTRUCTION M 24-Mar-1968 ARAMCO WASIT GAS PLANT 3 KHURSANIYA PO 19 AGUILA, JOSELITO PARAYNO P.O. BOX 83 AL KHOBAR 31952 C/O AL ZAMIL M 19-Jun-1973 EXCHANGE AL KHOBAR KING SAUD ST. -

Anabolic–Androgenic Steroid Abuse Among Gym Users, Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia

medicina Article Anabolic–Androgenic Steroid Abuse among Gym Users, Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia Walied Albaker 1, Ali Alkhars 1, Yasir Elamin 1, Noor Jatoi 1, Dhuha Boumarah 1 and Mohammed Al-Hariri 2,* 1 Department of Internal Medicine, College of Medicine, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, P.O. Box 2114, Dammam 31451, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] (W.A.); [email protected] (A.A.); [email protected] (Y.E.); [email protected] (N.J.); [email protected] (D.B.) 2 Department of Physiology, College of Medicine, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, P.O. Box 2114, Dammam 31451, Saudi Arabia * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +96-650-727-5028 Abstract: Background and Objectives: The main aim of the present study was to assess the use of androgenic–anabolic steroids (AAS) and to investigate its potentially unfavorable effects among gym members attending gym fitness facilities in Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia. Materials and Methods: A cross-sectional questionnaire-based study was carried out during the summer of 2017. Male gym users in the Eastern Province region of Saudi Arabia were the respondents. Information on socio-demographics, use of AAS, knowledge, and awareness about its side effects were collected using a self-administered questionnaire. Results: The prevalence of AAS consumption among trainees in Eastern Province was 21.3%. The percentage was highest among those 26–30 years of age (31.9%), followed by the 21–25 (27.4%) (p = 0.003) age group. Participants in the study were not aware of the potential adverse effects of AAS use. Adverse effects experienced by 77% of AAS users include Citation: Albaker, W.; Alkhars, A.; psychiatric problems (47%), acne (32.7%), hair loss (14.2%), and sexual dysfunction (10.7%). -

CODEALPHA3 CODEALPHA2 NAME AFG AF Afghanistan ALB AL

CODEALPHA3 CODEALPHA2 NAME AFG AF Afghanistan ALB AL Albania DZA DZ Algeria ASM AS American Samoa AND AD Andorra AGO AO Angola AIA AI Anguilla ATA AQ Antarctica ATG AG Antigua and Barbuda ARG AR Argentina ARM AM Armenia ABW AW Aruba AUS AU Australia AUT AT Austria AZE AZ Azerbaijan BHS BS Bahamas BHR BH Bahrain BGD BD Bangladesh BRB BB Barbados BLR BY Belarus BEL BE Belgium BLZ BZ Belize BEN BJ Benin BMU BM Bermuda BTN BT Bhutan BOL BO Bolivia BES BQ Bonaire BIH BA Bosnia and Herzegovina BWA BW Botswana BVT BV Bouvet Island BRA BR Brazil IOT IO British Indian Ocean Territory BRN BN Brunei Darussalam BGR BG Bulgaria BFA BF Burkina Faso BDI BI Burundi KHM KH Cambodia CMR CM Cameroon CAN CA Canada CPV CV Cape Verde CYM KY Cayman Islands CAF CF Central African Republic TCD TD Chad CHL CL Chile CHN CN China CXR CX Christmas Island CCK CC Cocos (Keeling) Islands COL CO Colombia COM KM Comoros COG CG Congo COD CD Democratic Republic of the Congo COK CK Cook Islands CRI CR Costa Rica HRV HR Croatia CUB CU Cuba CUW CW Cura?§ao CYP CY Cyprus CZE CZ Czech Republic DNK DK Denmark DJI DJ Djibouti DMA DM Dominica DOM DO Dominican Republic TLS TL Timor-Leste ECU EC Ecuador EGY EG Egypt SLV SV El Salvador GNQ GQ Equatorial Guinea ERI ER Eritrea EST EE Estonia ETH ET Ethiopia FLK FK Falkland Islands (Malvinas) FRO FO Faroe Islands FJI FJ Fiji FIN FI Finland FRA FR France GUF GF French Guiana PYF PF French Polynesia ATF TF French Southern Territories GAB GA Gabon GMB GM Gambia GEO GE Georgia DEU DE Germany GHA GH Ghana GIB GI Gibraltar GRC GR Greece GRL -

In Dammam Aquifer ...25

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to express my gratitude to the Almighty Allah, the cherisher and sustainer of the world, who gave me courage and patience to complete this work. I would like to express my hearty thanks to King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals for providing support for this research. My special thanks go to the Chairman of the Thesis Committee , Dr. Bassam Al-Tawabini for his unique, professional , exceptional and constant support and guidance. Acknowledgment is also due to the thesis committee members: Dr.Abdulaziz Al-Shaibani, and Dr. Mohammad Makkawi, for their contribution and guidance through the stages of this research. Acknowledgment is also due to Mr.Mahmoud Al-Manee, Manager of Metal Analytical Laboratory at SABIC Technology Center at Jubail for his help and encouragement. Thanks are also due to his staff, especially at the Environmental Section, who facilitated my work and analysis. Finally, I am indebted to my parents, especially my mother for her prayers, my wife and my children for their support, patience and understanding throughout this program. I would also like to extend my thanks to my friends for their unconditional support. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................... iii LIST OF TABLES ...................................................................................................... viii LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................... -

SWPC 7 Year Planning Statement – (2020 – 2026)

1 Table of Contents I. SWPC seven year statement ..................................................................................................................... 5 II. Glossary .............................................................................................................................................................. 6 III. Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 7 IV. SWPC Overview .............................................................................................................................................14 V. Desalination Capacity Plan .......................................................................................................................17 1. National Water Demand Context and Policies ............................................................................17 2. National Water Supply Context and Policies ................................................................................19 3. National Desalinated Water Need & Proposed Plants .............................................................24 4. Regional Outlook .....................................................................................................................................25 i. Eastern Supply Group ........................................................................................................................25 ii. Western Supply Group ......................................................................................................................28 -

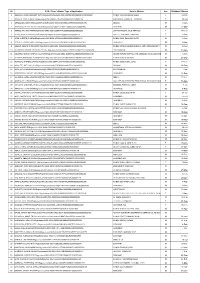

List RERB Hearing on 27March2015.Xlsx

SN V.I.N. / Voter's Name/ Type of Application Voter's Address Sex Birthdate / Biometrics 1 ABANGAN, ROSE MARGARET NATIVIDADRegistraonSA02-000A-J2470RNA20006825910300002067 PO BOX 15215 DAMMAM 31444 F 24-Oct-1970 2 ABASULA, VIOLETA ROYALESRegistraonSA02-000A-G2365VRA20006825910200002130 MOBARAKIA, CORNICHE , DAMMAM F 23-Jul-1965 3 ABRASALDO, GLENN ENCALLADORegistraonSA02-000A-A0282GEA10006825910300001991 ABQAIQ, M 2-Jan-1982 4 ABRASALDO, KEITH ENCALLADOCerficaonSA02-000A-C1190KEA10006825910300001995 DAMMAM M 11-Mar-1990 5 ABRIGO, MA. GINA MARTERegistraonSA02-000A-L2968MMA20006825910200002162 157 RAS TANURA, SAUDI ARAMCO F 29-Dec-1968 6 ACAIN, SHIRLEY SACABINCerficaonSA02-000A-F0163SSA20006825910200002131 AREA 77, AL RAWDA, DAMMAM F 1-Jun-1963 7 ACOB, ALBERTO JR AGPALORegistraonSA02-000A-K0765AAA10006825910200002174 PO BOX 1538, DAMMAM 31972 M 7-Nov-1965 8 ACUNA, LEONARDO MAGTIBAYRegistraonSA02-000A-D0669LMA10006825910300001837 AL KHOBAR M 6-Apr-1969 9 ADAJAR, RENATO JR FETALCORINRegistraonSA02-000A-K0365RFA10006825910300001826 PO BOX 31729 ALKHOBAR 31952 AL HOTY ESTABLISHMENT M 3-Nov-1965 10 AGOHAYON, PAQUITO JR KELONG KELONGRegistraonSA02-000A-A1372PKA10006825910300002078 91# DAMMAM M 13-Jan-1972 11 AGUDERA, MARIA VICTORIA VILLANUEVARegistraonSA02-000A-J0566MVA10006825910300001748 ARMED FORCES HOSPITAL KING ABDULAZIZ NAVAL BASE JUBAIL POM BOX 413KI 5-Oct-1966 12 ALAVERA, FERDINAND ALAN MALANOGRegistraonSA02-000A-I2869FMA10006825910300001830 PO BOX 60161 ALKHOBAR M 28-Sep-1969 13 ALBACETE, ANNABELLE ABRIOLRegistraonSA02-000A-L1765AAA20006825910300001732 -

Mangrove Forests As Traps for Marine Litter

Mangrove forests as traps for marine litter Item Type Article Authors Martin, Cecilia; Almahasheer, Hanan; Duarte, Carlos M. Citation Martin C, Almahasheer H, Duarte CM (2019) Mangrove forests as traps for marine litter. Environmental Pollution 247: 499–508. Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2019.01.067. Eprint version Publisher's Version/PDF DOI 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.01.067 Publisher Elsevier BV Journal Environmental Pollution Rights Under a Creative Commons license Download date 23/09/2021 09:45:40 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10754/631046 Environmental Pollution 247 (2019) 499e508 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Environmental Pollution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/envpol Mangrove forests as traps for marine litter* * Cecilia Martin a, , Hanan Almahasheer b, Carlos M. Duarte a a Red Sea Research Center and Computational Bioscience Research Center, King Abdullah University of Science and Technology, Thuwal, 23955, Saudi Arabia b Department of Biology, College of Science, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University (IAU), Dammam, 31441-1982, Saudi Arabia article info abstract Article history: To verify weather mangroves act as sinks for marine litter, we surveyed through visual census 20 forests Received 27 September 2018 along the Red Sea and the Arabian Gulf, both in inhabited and remote locations. Anthropogenic debris Received in revised form items were counted and classified along transects, and the influence of main drivers of distribution were 15 January 2019 considered (i.e. land-based and ocean-based sources, density of the forest and properties of the object). -

Toll Collection System Using RFID (613 Highway) Jubail-Dhahran Highway

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056 Volume: 07 Issue: 04 | Apr 2020 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072 Toll Collection System using RFID (613 highway) jubail-Dhahran highway Abdullah Al-Shehri1, Mansour Al-Qahtani2, Salah Al-Harbi3, Yami Shayan4, Ali Al-Hammadi5, Naif Al-Zahrani6 1-6Bachelor’s students, Electrical & Electronic Engineering Department, Jubail Industrial City, Saudi Arabia ----------------------------------------------------------------------------***-------------------------------------------------------------------------- Abstract: RFID is a modern technology which provides several benefits for many applications around the world. Highway 613 is needed for regular and continuous maintenance to make the highway road much better and provide many facilities for the users RFID is a modern technology which provides several benefits for many applications around the world. Radio frequency identification (RFID) is a technology that enable the electronic and wireless labeling and identification of objects humans and animals .Highway 613 is needed for regular and continuous maintenance to make the highway road much better and provide many facilities for the users. This paper is aimed to automate highway 613 for this purpose using RFID, Keywords: RFID, RFID reader, RFID tag, RFID sticker, PC, JIC. Introduction: There is another name for RFID called dedicated short range communication [DSRC]. There are three elements which are very important, Tag or Transponder - Reader or Interrogator - Data base (software) or computer. RFID is work when radio frequency reader scans the Tag for data and sends the information to data base which stores the data contained on the tag. The purpose of project is to use RFID as Toll Collection to make the highway payable automatically which we will use a unique RFID tag code on each vehicles. -

Metropolitan Dammam: City of Mega-Projects.” in Volume II of Greater Than Parts: a Metropolitan Opportunity, Edited by Shagun Mehrotra, Lincoln L

CASE 4 GREATER THAN PARTS GREATER THAN PARTS THAN PARTS GREATER Dammam, Saudi Arabia Public Disclosure Authorized City of Mega-Projects Antar AbouKorin, Abdulrahman Alsayel, and Hazem Abdelfattah A Metropolitan Opportunity Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Editors Shagun Mehrotra, Lincoln Lewis, Mariana Orloff, and Beth Olberding © 2020 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000; internet: www.worldbank.org Some rights reserved. This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contri- butions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, itsBoard of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Nothing herein shall constitute or be considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privileges and immunities of The World Bank, all of which are specifically reserved. Rights and Permissions This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo. Un- der the Creative Commons Attribution license, you are free to copy, distribute, transmit, and adapt this work, including for commercial purposes, under the following conditions: Translations—If you create a translation of this work, please add the following disclaimer along with the attribution: This translation was not created by The World Bank and should not be considered an official World Bank translation.