+ Qatif City Profile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

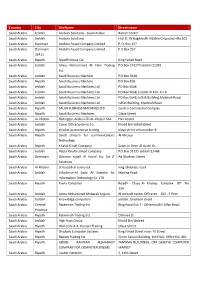

Country City Sitename Street Name Saudi Arabia Jeddah Arabian Solutions - Saudi Arabia Barom Center Saudi Arabia Jeddah Arabian Solutions Hial St

Country City SiteName Street name Saudi Arabia Jeddah Arabian Solutions - Saudi Arabia Barom Center Saudi Arabia Jeddah Arabian Solutions Hial St. W.Bogddadih AlZabin Cmpound villa 102 Saudi Arabia Damman Abdulla Fouad Company Limited P. O. Box 257 Saudi Arabia Dammam Abdulla Fouad Company Limited P O Box 257 31411 Saudi Arabia Riyadh Riyadh House Est. King Fahad Road Saudi Arabia Jeddah Idress Mohammed Ali Fatni Trading P.O.Box 132270 Jeddah 21382 Est. Saudi Arabia Jeddah Saudi Business Machine P.O.Box 5648 Saudi Arabia Riyadh Saudi Business Machine P.O Box 818 Saudi Arabia Jeddah Saudi Business Machines Ltd PO Box 5648 Saudi Arabia Jeddah Saudi Business Machines Ltd. PO Box 5648, Jeddah 21432, K S A Saudi Arabia Jeddah Saudi Business Machines Ltd. PO Box 5648, Juffali Building,Madinah Road Saudi Arabia Jeddah Saudi Business Machines Ltd. Juffali Building, Madinah Road Saudi Arabia Riyadh SAUDI BUSINESS MACHINES LTD. Centria Commercial Complex Saudi Arabia Riyadh Saudi Business Machines Olaya Street Saudi Arabia Al-Khobar Redington Arabia LTD AL-Khobar KSA Hail Center Saudi Arabia Jeddah Canar Office Systems Co Khalid Bin Walid Street Saudi Arabia Riyadh shrakat partnerships trading olaya street villa number 8 Saudi Arabia Riyadh Saudi Unicom for communications Al-Mrouje technology Saudi Arabia Riyadh Khalid Al Safi Company Salah Al-Deen Al-Ayubi St., Saudi Arabia Jeddah Azizia Panda United Company P.O.Box 33333 Jeddah 21448 Saudi Arabia Dammam Othman Yousif Al Yousif Est. for IT Ad Dhahran Street Solutions Saudi Arabia Al Khober al hasoob al asiavy est. king abdulaziz road Saudi Arabia Jeddah EchoServe-Al Sada Al Shamila for Madina Road Information Technology Co. -

+ CPI PROFILE Al Baha

The Future Saudi Cities Programme 2 CPI PROFILE – Al Baha ©Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs , 2019 King Fahd National Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs CPI PROFILE Al Baha. / Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs .- Riyadh , 2019 ..p ; ..cm ISBN: 978-603-8279-34-2 1- City planning - Al Baha I-Title 309.2625314 dc 1440/8345 L.D. no. 1440/8345 ISBN: 978-603-8279-34-2 © 2018. Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs and United Nations Human Settlements Programme. All rights reserved Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs P.O. Box : 935 - King Fahd, Riyadh, 11136 Tel: 00966114569999 https://www.momra.gov.sa/ United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) P.O. Box 30030, 00100 Nairobi GPO KENYA Tel: 254-020-7623120 (Central Office) www.unhabitat.org Disclaimer The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs, the United Nations Human Settlements Programme, the United Nations or its Member States. Excerpts may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Authors: UN-Habitat (Riyadh) Un-Habitat (Nairob) Mr. John Obure Mr. Robert Ndugwa Mr. Mohammed Al Ahmed Mr. Antony Abilla Mr. Bader Al Dawsari Ms. -

Op-Ed Contributor - ‘Peak Oil’ Is a Wa…

9/4/2009 Op-Ed Contributor - ‘Peak Oil’ Is a Wa… August 25, 2009 OP-ED CONT RIBUT OR ‘Peak Oil’ Is a Waste of Energy By MICHAEL LYNCH Amherst, Mass. REMEMBER “peak oil”? It’s the theory that geological scarcity will at some point make it impossible for global petroleum production to avoid falling, heralding the end of the oil age and, potentially, economic catastrophe. Well, just when we thought that the collapse in oil prices since last summer had put an end to such talk, along comes Fatih Birol, the top economist at the International Energy Agency, to insist that we’ll reach the peak moment in 10 years, a decade sooner than most previous predictions (although a few ardent pessimists believe the moment of no return has already come and gone). Like many Malthusian beliefs, peak oil theory has been promoted by a motivated group of scientists and laymen who base their conclusions on poor analyses of data and misinterpretations of technical material. But because the news media and prominent figures like James Schlesinger, a former secretary of energy, and the oilman T. Boone Pickens have taken peak oil seriously, the public is understandably alarmed. A careful examination of the facts shows that most arguments about peak oil are based on anecdotal information, vague references and ignorance of how the oil industry goes about finding fields and extracting petroleum. And this has been demonstrated over and over again: the founder of the Association for the Study of Peak Oil first claimed in 1989 that the peak had already been reached, and Mr. -

Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease 38 (2020) 101901

Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease 38 (2020) 101901 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/tmaid Original article Incidence of COVID-19 among returning travelers in quarantine facilities: A longitudinal study and lessons learned Jaffar A. Al-Tawfiq a,b,c,*, Amar Sattar d, Husain Al-Khadra d, Saeed Al-Qahtani d, Mobarak Al-Mulhim e, Omar Al-Omoush d, Hatim O. Kheir d a Specialty Internal Medicine and Quality Department, Johns Hopkins Aramco Healthcare, Dhahran, Saudi Arabia b Infectious Disease Division, Department of Medicine, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN, USA c Infectious Disease Division, Department of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA d Primary Care Division, Johns Hopkins Aramco Healthcare, Dhahran, Saudi Arabia e King Fahd Specialist Hospital Dammam, Saudi Arabia ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Introduction: The emergence of the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) had resulted SARS-CoV-2 in an unpresented global pandemic. In the initial events, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia implemented mandatory COVID-19 quarantine of returning travelers in order to contain COVID-19 cases. Quarantine Materials and methods: This is a longitudinal study of the arriving travelers to Quarantine facilities and the Travelers prevalence of positive SARS-CoV-2 as detected by RT-PCR. Results: During the study period, there was a total of 1928 returning travelers with 1273 (66%) males. The age range was 28 days–69 years. Of all the travelers, 23 (1.2%) tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. Of the firstswab, 14/ 1928 (0.7%) tested positive. -

Saudi Arabia.Pdf

A saudi man with his horse Performance of Al Ardha, the Saudi national dance in Riyadh Flickr / Charles Roffey Flickr / Abraham Puthoor SAUDI ARABIA Dec. 2019 Table of Contents Chapter 1 | Geography . 6 Introduction . 6 Geographical Divisions . 7 Asir, the Southern Region � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �7 Rub al-Khali and the Southern Region � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �8 Hejaz, the Western Region � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �8 Nejd, the Central Region � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �9 The Eastern Region � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �9 Topographical Divisions . .. 9 Deserts and Mountains � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �9 Climate . .. 10 Bodies of Water . 11 Red Sea � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 11 Persian Gulf � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 11 Wadis � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 11 Major Cities . 12 Riyadh � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �12 Jeddah � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �13 Mecca � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � -

Saudi Arabia 2019

Saudi Arabia 2019 Saudi Arabia 2019 1 Table of Contents Doing Business in Saudi Arabia ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Market Overview ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 Market Challenges ..................................................................................................................................................... 6 Market Opportunities ................................................................................................................................................ 8 Market Entry Strategy ............................................................................................................................................... 9 Political Environment................................................................................................................................................... 10 Selling US Products & Services .................................................................................................................................... 11 Agents and Distributors ........................................................................................................................................... 11 Establishing an Office ............................................................................................................................................. -

Desert Storm"

VECTORS AND WAR - "DESERT STORM" By Joseph Conlon [email protected] The awesome technological marvels of laser-guided munitions and rocketry riveted everyone's attention during the recent Persian Gulf War. Yet, an aspect of the war that received comparatively little media attention was the constant battle waged against potential disease vectors by preventive medicine personnel from the coalition forces. The extraordinarily small number of casualties suffered in combat was no less remarkable than the low numbers of casualties due to vector-borne disease. Both statistics reflect an appreciation of thorough planning and the proper allocation of massive resources in accomplishing a mission against a well-equipped foe. A great many personnel were involved in the vector control effort from all of the uniformed services. This paper will address some of the unique vector control issues experienced before, during, and after the hostilities by the First Marine Expeditionary Force (1st MEF), a contingent of 45,000 Marines headquartered at Al Jubail, a Saudi port 140 miles south of Kuwait. Elements of the 1st MEF arrived on Saudi soil in mid-August, 1991. The 1st MEF was given the initial task of guarding the coastal road system in the Eastern Province, to prevent hostile forces from capturing the major Saudi ports and airfields located there. Combat units of the 1st Marine Division were involved in the Battle of Khafji, prior to the main campaign. In addition, 1st MEF comprised the primary force breaching the Iraqi defenses in southern Kuwait, culminating in the tank battle at the International Airport. THE VECTOR-BORNE DISEASE THREAT The vector control problems encountered during the five months preceding the war were far worse than those during the actual fighting. -

EPSE PROFILE-19Th Edition

Electrical Power Systems Establishment PROFILE 19th EDITION May, 2019 www.eps-est.com TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION 2.0 ORGANIZATION INFORMATION 3.0 MESSAGES 3.1 MISSION 3.2 VISION 3.3 COMMITMENT STATEMENT 3.4 QA/QC STATEMENT 3.5 SAFETY STATMENT 4.0 ORGANIZATION CHART 5.0 AFFILIATIONS 6.0 RESOURCES LISTING 6.1 MANPOWER 6.2 CONSTRUCTION EQUIPMENT & TOOLS 6.3 TESTING EQUIPMENT 7.0 BRIEF BUSINESS EXPOSURE 7.1 EQUIPMENT EXPERTISE 7.2 SERVICES 7.3 MAIN CUSTOMERS LIST 8.0 PROJECT LISTING 8.1 ON GOING JOBS 8.2 COMPLETED JOBS Electrical Power Systems Est. Profile 19th Edition May, 2019 PAGE 2 OF 33 1.0 INTRODUCTION Electrical Power Systems Est., (EPSE) was founded in 1989 under the name of Electronics Systems Est. (ESE). Established primarily to provide general services in instrumentation, calibration and personal computer trade, it then revolutionized its interests to the more technical field of Control and Monitoring Systems primarily for the Electric Power utilities. Within a short period of time in this new field of interest, it has achieved a remarkable and outstanding performance that gained the appreciation and acknowledgment of fine clients such as ABB, which from thence entrusted sensitive related jobs to the Establishment. Realizing the soaring demand for services in this specialized field and where only few Saudi firms have ventured, the management was prompted to enhance and confine ESE activities within the bounds of Electric Power Control and Monitoring Systems. In late 1998, Electronics Systems Est. (ESE) was renamed Electrical Power Systems Establishment (EPSE) to appropriately symbolize its specialized activities in the field of Electricity. -

Rapid Urbanization and Sustainability in Saudi Arabia: the Case of Dammam Metropolitan Area

Journal of Sustainable Development; Vol. 8, No. 9; 2015 ISSN 1913-9063 E-ISSN 1913-9071 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Rapid Urbanization and Sustainability in Saudi Arabia: The Case of Dammam Metropolitan Area Antar A. Abou-Korin1 & Faez Saad Al-Shihri1 1 Department of Urban & Regional Planning, College of Architecture & Planning, University of Dammam, Saudi Arabia Correspondence: Antar A. Abou-Korin, Dept. of Urban & Regional Planning, College of Architecture & Planning, University of Dammam, P.O. Box: 2397, Dammam 31451, Saudi Arabia. Tel: 966-5-4788-5140. E-mail: [email protected] Received: August 7, 2015 Accepted: August 26, 2015 Online Published: October 24, 2015 doi:10.5539/jsd.v8n9p52 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/jsd.v8n9p52 Abstract Rapid urbanization is a characterizing feature of urban change in Saudi Arabia, especially in its large metropolitan areas such as Riyadh, Dammam Metropolitan Area (DMA), Jeddah and Makkah. Such rapid urbanization has created many urban problems that contradict with the principles of sustainability. The paper argues that "Urban Sustainability" is a necessary policy in the case of DMA, and tries to define the needed approaches and actions to implement such policy in the region. In doing so, the paper starts by highlighting the rapid rate of urbanization in the Saudi Arabia in general; and in DMA in particular. Then, the paper presents an analysis of the unsustainable urbanization practices and problems in DMA. The paper then presents a literature review about sustainable urbanization approaches and requirements, focusing on developing countries. Finally, the paper recommends the necessary approaches and actions to achieve the proposed "Urban Sustainability" policy in DMA. -

Us Military Assistance to Saudi Arabia, 1942-1964

DANCE OF SWORDS: U.S. MILITARY ASSISTANCE TO SAUDI ARABIA, 1942-1964 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Bruce R. Nardulli, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2002 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Allan R. Millett, Adviser Professor Peter L. Hahn _______________________ Adviser Professor David Stebenne History Graduate Program UMI Number: 3081949 ________________________________________________________ UMI Microform 3081949 Copyright 2003 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ____________________________________________________________ ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road PO Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 ABSTRACT The United States and Saudi Arabia have a long and complex history of security relations. These relations evolved under conditions in which both countries understood and valued the need for cooperation, but also were aware of its limits and the dangers of too close a partnership. U.S. security dealings with Saudi Arabia are an extreme, perhaps unique, case of how security ties unfolded under conditions in which sensitivities to those ties were always a central —oftentimes dominating—consideration. This was especially true in the most delicate area of military assistance. Distinct patterns of behavior by the two countries emerged as a result, patterns that continue to this day. This dissertation examines the first twenty years of the U.S.-Saudi military assistance relationship. It seeks to identify the principal factors responsible for how and why the military assistance process evolved as it did, focusing on the objectives and constraints of both U.S. -

READ Middle East Brief 101 (PDF)

Judith and Sidney Swartz Director and Professor of Politics Repression and Protest in Saudi Arabia Shai Feldman Associate Director Kristina Cherniahivsky Pascal Menoret Charles (Corky) Goodman Professor of Middle East History and Associate Director for Research few months after 9/11, a Saudi prince working in Naghmeh Sohrabi A government declared during an interview: “We, who Senior Fellow studied in the West, are of course in favor of democracy. As a Abdel Monem Said Aly, PhD matter of fact, we are the only true democrats in this country. Goldman Senior Fellow Khalil Shikaki, PhD But if we give people the right to vote, who do you think they’ll elect? The Islamists. It is not that we don’t want to Myra and Robert Kraft Professor 1 of Arab Politics introduce democracy in Arabia—but would it be reasonable?” Eva Bellin Underlying this position is the assumption that Islamists Henry J. Leir Professor of the Economics of the Middle East are enemies of democracy, even if they use democratic Nader Habibi means to come to power. Perhaps unwittingly, however, the Sylvia K. Hassenfeld Professor prince was also acknowledging the Islamists’ legitimacy, of Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies Kanan Makiya as well as the unpopularity of the royal family. The fear of Islamists disrupting Saudi politics has prompted very high Renée and Lester Crown Professor of Modern Middle East Studies levels of repression since the 1979 Iranian revolution and the Pascal Menoret occupation of the Mecca Grand Mosque by an armed Salafi Neubauer Junior Research Fellow group.2 In the past decades, dozens of thousands have been Richard A. -

Saudi Arabia 2019 Crime & Safety Report: Riyadh

Saudi Arabia 2019 Crime & Safety Report: Riyadh This is an annual report produced in conjunction with the Regional Security Office at the U.S. Embassy in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The current U.S. Department of State Travel Advisory at the date of this report’s publication assesses Saudi Arabia at Level 2, indicating travelers should exercise increased caution due to terrorism. Overall Crime and Safety Situation The U.S. Embassy in Riyadh does not assume responsibility for the professional ability or integrity of the persons or firms appearing in this report. The American Citizens’ Services unit (ACS) cannot recommend a particular individual or location, and assumes no responsibility for the quality of service provided. Review OSAC’s Saudi Arabia-specific page for original OSAC reporting, consular messages, and contact information, some of which may be available only to private-sector representatives with an OSAC password. Crime Threats There is minimal risk from crime in Riyadh. Crime in Saudi Arabia has increased over recent years but remains at levels far below most major metropolitan areas in the United States. Criminal activity does not typically target foreigners and is mostly drug-related. For more information, review OSAC’s Report, Shaken: The Don’ts of Alcohol Abroad. Cybersecurity Issues The Saudi government continues to expand its cybersecurity activities. Major cyber-attacks in 2012 and 2016 focused on the private sector and on Saudi government agencies, spurring action from Saudi policymakers and local business leaders. The Saudi government, through the Ministry of Interior (MOI), continues to develop and expand its collaboration with the U.S.