Stolen Art and the Act of State Doctrine: an Unsettled Past and an Uncertain Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Art Collection of Peter Watson (1908–1956)

099-105dnh 10 Clark Watson collection_baj gs 28/09/2015 15:10 Page 101 The BRITISH ART Journal Volume XVI, No. 2 The art collection of Peter Watson (1908–1956) Adrian Clark 9 The co-author of a ously been assembled. Generally speaking, he only collected new the work of non-British artists until the War, when circum- biography of Peter stances forced him to live in London for a prolonged period and Watson identifies the he became familiar with the contemporary British art world. works of art in his collection: Adrian The Russian émigré artist Pavel Tchelitchev was one of the Clark and Jeremy first artists whose works Watson began to collect, buying a Dronfield, Peter picture by him at an exhibition in London as early as July Watson, Queer Saint. 193210 (when Watson was twenty-three).11 Then in February The cultured life of and March 1933 Watson bought pictures by him from Tooth’s Peter Watson who 12 shook 20th-century in London. Having lived in Paris for considerable periods in art and shocked high the second half of the 1930s and got to know the contempo- society, John Blake rary French art scene, Watson left Paris for London at the start Publishing Ltd, of the War and subsequently dispatched to America for safe- pp415, £25 13 ISBN 978-1784186005 keeping Picasso’s La Femme Lisant of 1934. The picture came under the control of his boyfriend Denham Fouts.14 eter Watson According to Isherwood’s thinly veiled fictional account,15 (1908–1956) Fouts sold the picture to someone he met at a party for was of consid- P $9,500.16 Watson took with him few, if any, pictures from Paris erable cultural to London and he left a Romanian friend, Sherban Sidery, to significance in the look after his empty flat at 44 rue du Bac in the VIIe mid-20th-century art arrondissement. -

AUSSTELLUNGSFÜHRER Saalplan

DE 02.11.2017 – 04.03.2018 AUSSTELLUNGSFÜHRER Saalplan 5 C 6 b D 7 4 8 3 E 2 9 Kino 1 - A Provenienz forschung Untergeschoss Garde- robe A Berliner Secession 1 Angriff auf die Moderne B Die Brücke 2 Verfallskunst C Der Blaue Reiter 3 «Wider den undeutschen Geist» D Das Bauhaus 4 Die Ausstellung «Entartete Kunst» E Spätexpressionismus 5 Kunstretter oder Verwerter? und Verismus 6 Moderne Meister versteigert 7 Kunstraub in Frankreich 8 Rückführung geraubter Kunst 9 Die sogenannte Klassische Moderne Einführung Die Ausstellung zeigt eine erste, vorläufige Bestandsaufnahme des «Kunstfunds Gurlitt». Der konkrete Fall der aufgefundenen und noch weiter zu erforschenden Werke wird dabei zum Anlass genommen, die NS-Kunstpolitik und das System des NS-Kunstraubs beispielhaft zu behandeln. Das Kunstmuseum Bern und die Bundeskunsthalle in Bonn haben dabei eng zusammengearbeitet. Hier in Bern wird das Kapitel «Entartete Kunst» dargestellt und in einem grösseren Zusammenhang erläutert, der auch die Geschehnisse in der Schweiz mit in den Blick nimmt. Besonderes Augenmerk liegt auf den Schicksalen der von Feme und Verfolgung betroffenen Künstlerinnen und Künstler, sowie der Biographie von Hildebrand Gurlitt in all ihren Widersprüchen. In der «Werkstatt Provenienzforschung» können Sie an Beispielen selbst die Methoden und Herausforderungen der Provenienzforschung nach- vollziehen. Was ist der «Kunstfund Gurlitt»? Der «Kunstfund Gurlitt» umfasst Kunstwerke aus dem Besitz Cornelius Gurlitts (1932–2014), Sohn des deutschen Kunsthändlers Hildebrand Gurlitt (1895–1956). Der Grossteil der Werke wurde 2012 in der Münchner Wohnung von Cornelius Gurlitt infolge eines Steuerermittlungsver- fahrens beschlagnahmt. Durch einen Bericht des Nachrichtenmagazins «Focus» am 3. November 2013 erfuhr die Öffentlichkeit von der Existenz des Bestandes. -

Germany 2020 Human Rights Report

GERMANY 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Germany is a constitutional democracy. Citizens choose their representatives periodically in free and fair multiparty elections. The lower chamber of the federal parliament (Bundestag) elects the chancellor as head of the federal government. The second legislative chamber, the Federal Council (Bundesrat), represents the 16 states at the federal level and is composed of members of the state governments. The country’s 16 states exercise considerable autonomy, including over law enforcement and education. Observers considered the national elections for the Bundestag in 2017 to have been free and fair, as were state elections in 2018, 2019, and 2020. Responsibility for internal and border security is shared by the police forces of the 16 states, the Federal Criminal Police Office, and the federal police. The states’ police forces report to their respective interior ministries; the federal police forces report to the Federal Ministry of the Interior. The Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution and the state offices for the protection of the constitution are responsible for gathering intelligence on threats to domestic order and other security functions. The Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution reports to the Federal Ministry of the Interior, and the state offices for the same function report to their respective ministries of the interior. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over security forces. Members of the security forces committed few abuses. Significant human rights issues included: crimes involving violence motivated by anti-Semitism and crimes involving violence targeting members of ethnic or religious minority groups motivated by Islamophobia or other forms of right-wing extremism. -

A Moral Persuasion: the Nazi-Looted Art Recoveries of the Max Stern Art Restitution Project, 2002-2013

A MORAL PERSUASION: THE NAZI-LOOTED ART RECOVERIES OF THE MAX STERN ART RESTITUTION PROJECT, 2002-2013 by Sara J. Angel A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of PhD Graduate Department Art University of Toronto © Copyright by Sara J. Angel 2017 PhD Abstract A Moral Persuasion: The Nazi-Looted Art Recoveries of the Max Stern Art Restitution Project, 2002-2013 Sara J. Angel Department of Art University of Toronto Year of convocation: 2017 In 1937, under Gestapo orders, the Nazis forced the Düsseldorf-born Jewish art dealer Max Stern to sell over 200 of his family’s paintings at Lempertz, a Cologne-based auction house. Stern kept this fact a secret for the rest of his life despite escaping from Europe to Montreal, Canada, where he settled and became one of the country’s leading art dealers by the mid-twentieth century. A decade after Stern’s death in 1987, his heirs (McGill University, Concordia University, and The Hebrew University of Jerusalem) discovered the details of what he had lost, and how in the post-war years Stern travelled to Germany in an attempt to reclaim his art. To honour the memory of Max Stern, they founded the Montreal- based Max Stern Art Restitution Project in 2002, dedicated to regaining ownership of his art and to the study of Holocaust-era plunder and recovery. This dissertation presents the histories and circumstances of the first twelve paintings claimed by the organization in the context of the broader history of Nazi-looted art between 1933-2012. Organized into thematic chapters, the dissertation documents how, by following a carefully devised approach of moral persuasion that combines practices like publicity, provenance studies, law enforcement, and legal precedents, the Max Stern Art Restitution Project set international precedents in the return of cultural property. -

Looted Art at Documenta 14 by Eleonora Vratskidou

ISSN: 2511–7602 Journal for Art Market Studies 2 (2018) A Review: Stories of wheels within wheels: looted art at documenta 14 by Eleonora Vratskidou While dOCUMENTA 13 (2012) reflected on the annihilation of cultural heritage, taking as a starting point the destruction of the two monumental Buddha statues in Bamiyan, Afghanistan, by the Taliban in 2001,1 the recent documenta 14 (2017) actively addressed the question of art theft and war spoliations, taking as its point of departure the highly controversial case of the Gurlitt art hoard. The circa 1,500 artworks uncovered in the possession of Cornelius Gurlitt (1934-2014), inherited from his father Hildebrand Gurlitt (1895-1956), one of the official art dealers of the Nazi regime, brought back to the surface aspects of a past that Germany is still in the process of coming to terms with. Initially, the intention of artistic director Adam Szymczyk had been to showcase the then unseen Gurlitt estate in the Neue Galerie in Kassel as part of documenta 14. Revisiting the tensed discussions on the status of the witness with regard to the historical experi- ence of the Holocaust (as addressed by Raul Hilberg, Dori Laub or Claude Lanzmann), Adam Szymczyk, in a conversation with the art historian Alexander Alberro and partici- pant artists Hans Haacke and Maria Eichhorn, reflected on plundered art works as “wit- nessing objects”, which in their material and visual specificity are able to give testament to an act of barbarism almost inexpressible by means of language.2 1 See mainly the text by artistic director Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, On the Destruction of Art —or Conflict and Art, or Trauma and the Art of Healing, and the postcript to it, Dario Gamboni’s article World Herit- age: Shield or Target, in the exhibition catalogue edited by Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev and Katrin Sauer- länder, The Book of Books (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2012), 282-295, as well as the commissioned project by Michael Rakowitz, What Dust Will Rise (2012). -

Nazi-Looted Art and Its Legacies: Introduction

Nazi-Looted Art and Its Legacies: Introduction Andreas Huyssen, Anson Rabinbach, and Avinoam Shalem In early 2012 German officials investigating violations of tax law discovered a trove of mainly nineteenth- and early twentieth-century European paintings and drawings in the Munich apartment and Salzburg house of Cornelius Gurlitt, the reclusive son of the prominent art dealer Hildebrand Gurlitt. The elder Gurlitt had worked for the Nazis but also counted a number of artists despised by them among his friends. Since then, the story of the Gurlitt collec- tion has made headlines worldwide. Beyond the bizarre obsession of the aging son, who lived with and for his artworks hidden from public view, the case raises fundamental questions about the role of art dealers during and after the Third Reich, the mechanics of a largely secretive and insufficiently docu- mented market in looted art, the complicity of art historians and business associations, the shortcomings of postwar denazification, the failure of courts and governments to adjudicate claims, and the unwillingness of museums to determine the provenance not just of Cornelius Gurlitt’s holdings but of Generous funding for the conference was provided by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, the German Academic Exchange Service, and Columbia’s Institute for Israel and Jewish Studies. We are also grateful for a donation by Lee Bollinger and Jean Magnano Bollinger. New York’s Jewish Museum provided a festive space for the opening lecture. At Columbia, the conference was cosponsored by the Heyman Center for the Humanities, the Department of History, the University Seminar on Cultural Memory, the Middle East Institute, and the Department of Germanic Languages. -

How to Deal with Nazi-Looted Art After Cornelius Gurlitt

PRECLUDING THE STATUTE OF LIMITATIONS? HOW TO DEAL WITH NAZI-LOOTED ART AFTER CORNELIUS GURLITT Phillip Hellwege* The Nazi regime collapsed seventy years ago; still today, we are concerned about the restitution of Nazi-looted art. In recent decades, the public debate in Germany has often focused on restitution by public museums and other public bodies. The recent case of Cornelius Gurlitt has raised the issue of restitution of Nazi-looted art by private individu- als and private entities. German law is clear about this issue: property based claims are time-barred after thirty years. Thus, according to Ger- man law, there is little hope that the original owners will have an en- forceable claim for the restitution of such art. Early in 2014, the Bavarian State Government proposed a legislative reform of the Ger- man Civil Code. The draft bill aims to re-open property based claims for restitution. The draft bill is a direct reaction to the case of Cornelius Gurlitt. This article analyzes the availability of property based claims for the restitution of Nazi-looted art under German law and critically as- sesses the Bavarian State Government's draft bill. My conclusion is not encouraging for the original owners of Nazi-looted art. Even though the Bavarian draft bill breeds hope among Nazi victims and their heirs, who are led to believe that they now have enforceable claims against the present possessors of what was theirs, the truth is that many original owners have forever lost ownership of their art. Re-opening property based claims will not be of any help to these victims, because it is still * Professor of Private Law, Commercial Law, and Legal History, University Augsburg, Germany. -

Why Degenerate? from Nordau to Nolde and Beyond

The University of Edinburgh/National Galleries of Scotland Why Degenerate? From Nordau to Nolde and Beyond Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Interieur mit nackter Liegender und Mann (Interior with Nude Woman and Man), 1924 Saturday 13 October 2018, 9am - 5pm Hawthornden Lecture Theatre, Scottish National Gallery, The Mound, Edinburgh, EH2 2EL This one-day Research Forum for German Visual Culture symposium, organised by Dr Christian Weikop (ECA) and Frances Blythe (ECA), in collaboration with the National Galleries of Scotland, celebrates an exhibition retrospective of one of Germany’s greatest Expressionist artists, namely Emil Nolde (1867-1956). In the late 1930s, the National Socialist regime would condemn Nolde’s art as ‘degenerate’ and he would become a central figure of their Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) exhibition, which started in Munich and travelled to twelve other cities between 1937 and 1941. The aim of this international symposium, which features world-leading experts on modern German art, is to consider the inception, reception and reverberations of the notion of ‘Entartung’ (Degeneration), whilst challenging and updating existing orthodoxies in the field. Moving beyond the ideas underpinning the ‘Degenerate Art’ reconstruction exhibition at LACMA (1991), and more recently at the Neue Galerie, New York (2014), with their attendant catalogue scholarship focusing chiefly on the events of 1937, this project seeks to produce a fresh survey of the roots and developmental branches of the concept of ‘degeneration’. In this symposium, the -

COMPLAINT and FREISTAAT BAYERN, A/K/A the FREE ) STATE of BAVARIA, a Political Subdivision of a ) Foreign State, ) Defendants

Case 1:16-cv-09360-RJS Document 1 Filed 12/05/16 Page 1 of 51 Nicholas M. O’Donnell Sullivan & Worcester LLP One Post Office Square Boston, MA 02108 617- 338-2800 Attorneys for Plaintiffs UNITED STATE DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ) MICHAEL R. HULTON and PENNY R. HULTON, ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ECF Case ) - against - ) ) Case No. 16-cv-9360 BAYERISCHE ) STAATSGEMÄLDESAMMLUNGEN, a/k/a THE ) BAVARIAN STATE PAINTINGS COLLECTIONS, ) COMPLAINT and FREISTAAT BAYERN, a/k/a THE FREE ) STATE OF BAVARIA, a political subdivision of a ) foreign state, ) Defendants. ) ) ) This is a civil action by Plaintiffs Dr. Michael R. Hulton (“Dr. Hulton”) and Penny R. Hulton (“Mrs. Hulton,” together with Dr. Hulton, the “Hultons” or the “Plaintiffs”) for the restitution of a collection of paintings, owned by and taken from the renowned German Jewish art dealer and art collector Alfred Flechtheim (“Flechtheim”) as a result of National Socialist persecution. The Hultons are the sole heirs of Flechtheim. The paintings at issue are currently in the possession of Defendants the Freistaat Bayern (the Free State of Bavaria, or “Bavaria”) and the Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen (the Bavarian State Paintings Collections, or “BSGS,” together with Bavaria, “Defendants”). Case 1:16-cv-09360-RJS Document 1 Filed 12/05/16 Page 2 of 51 INTRODUCTORY STATEMENT 1. This is an action to recover eight paintings that were owned by Flechtheim, the preeminent dealer in Expressionist and Modernist Art of the Weimar Republic era in Germany (the “Paintings”). Flechtheim fled Nazi Germany in 1933 in mortal fear and to save his life. These Paintings were part of his privately owned large art collection and were lost to Flechtheim due to the policy of racial persecution and genocide. -

Resolved Stolen Art Claims

RESOLVED STOLEN ART CLAIMS CLAIMS FOR ART STOLEN DURING THE NAZI ERA AND WORLD WAR II, INCLUDING NAZI-LOOTED ART AND TROPHY ART* DATE OF RETURN/ CLAIM CLAIM COUNTRY† RESOLUTION MADE BY RECEIVED BY ARTWORK(S) MODE ‡ Australia 2000 Heirs of Johnny van Painting No Litigation Federico Gentili Haeften, British by Cornelius Bega - Monetary di Giuseppe gallery owner settlement1 who sold the painting to Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide Australia 05/29/2014 Heirs of The National Painting No Litigation - Richard Gallery of “Head of a Man” Return - Semmel Victoria previously attributed Painting to Vincent van Gogh remains in museum on 12- month loan2 * This chart was compiled by the law firm of Herrick, Feinstein LLP from information derived from published news articles and services available mainly in the United States or on the Internet, as well as law journal articles, press releases, and other sources, consulted as of August 6, 2015. As a result, Herrick, Feinstein LLP makes no representations as to the accuracy of any of the information contained in the chart, and the chart necessarily omits resolved claims about which information is not readily available from these sources. Information about any additional claims or corrections to the material presented here would be greatly appreciated and may be sent to the Art Law Group, Herrick, Feinstein LLP, 2 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10016, USA, by fax to +1 (212) 592- 1500, or via email to: [email protected]. Please be sure to include a copy of or reference to the source material from which the information is derived. -

Guide De L'exposition

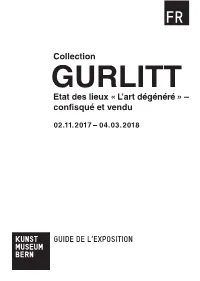

FR 02.11.2017 – 04.03.2018 GUIDE DE L‘EXPOSITION Plan des salles 5 C 6 b D 7 4 8 3 E 2 9 Cinéma 1 A Recherche de Sous-sol provenance Ves- tiaire A La Sécession de Berlin 1 Les attaques contre l’art moderne B Die Brücke 2 L’art décadent C Der Blaue Reiter 3 « Contre l’esprit non allemand » D Le Bauhaus 4 L’exposition « art dégénéré » E L’expressionnisme tardif 5 Sauveurs d’art ou profiteurs ? et le vérisme 6 Les maîtres modernes vendus aux enchères 7 Les spoliations artistiques en France 8 Les rapatriements d’œuvres spoliées 9 L’art moderne dit « classique » Introduction Cette exposition est un premier état des lieux, provisoire, du « trésor Gurlitt ». Les œuvres mises au jour, et dont l’étude doit encore être approfondie, constituent ici autant de cas concrets qui permettent d’exemplifier la politique artistique du régime nazi et son entreprise de spoliation d’œuvres d’art. Le Kunstmuseum Bern et la Bundeskunst- halle de Bonn ont travaillé en étroite collaboration à ce vaste projet d’exposition. Le Kunstmuseum Bern présente le volet « art dégénéré », exposé dans le contexte plus large des évènements de l’époque, y compris en Suisse. L’accent y est mis notamment sur le destin des artistes bannis et persécutés et sur la biographie de Hildebrand Gurlitt, dans tous ses aspects contradictoires. L’Atelier de recherche sur la provenance des œuvres vous propose d’appréhender les méthodes mises en œuvre par cette recherche et les défis auxquels elle doit faire face à travers un certain nombre d’exemples. -

Spoils of War

Spoils of War Special Edition International Conference "Database assisted documentation of lost cultural assets - Requirements, tendencies and forms of co-operation" Magdeburg, November 28-30 2001 Spoils of War. Special Edition Magdeburg Conference 2001 2 Imprint: Editorial Board: Bart Eeman, István Fodor, Michael M. Franz, Ekaterina Genieva, Wojciech Kowalski, Jacques Lust, Isabelle le Masne de Chermont, Anne Webber. Editor: Dr. Michael M. Franz. Technical assistance and Translation: Yvonne Sommermeyer and Svea Janner. Editorial address: Koordinierungsstelle für Kulturgutverluste City-Carré Kantstraße 5 39104 Magdeburg Phone: 0049 - 391 – 544 87 09 Fax: 0049 - 391 – 53 53 96 33 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.lostart.de Addresses of the members of the Editorial Board: ?Bart Eeman, Ministry of Economic Affairs, Directorate Economic Relations, Rue Gen Leman 60, 1040 Brussels, Belgium, phone: 0032/2065897, fax: 0032/25140389. ?István Fodor, Magyar Nemzeti Múzeum, Múzeum körni 14-16, 1088 Budapest, Hungary, phone: 36/1/3184259, fax: 36/1/3382/673. e-mail: [email protected]. ?Michael M. Franz, Koordinierungsstelle für Kulturgutverluste, City Carré, Kantstrasse 5, 39104 Magdeburg, Germany, phone: 0049/391/5448709, fax: 0049/391/53539633, e-mail: [email protected] anhalt.de. ?Ekaterina Genieva, All Russia State Library for Foreign Literature Moscow, Nikolojamskaja Street 1, 109 189 Moscow, Russia, phone: 7/095/915 3621, fax: 7/095/915 3637, e-mail: [email protected]. ?Wojciech Kowalski, University of Silesia, Department of Intellectual and Cultural Property Law, ul. Bankowa 8, 40 007 Katowice, Poland, phone/fax: 48/32/517104, phone: 48/32/588211, fax: 48/32/599188; e-mail: [email protected].