The Latitudes of Venus and Mercury in the Almagest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes for Origins-Astro, J. Hedberg © 2018

PHY 454 - origins-astro - J. Hedberg - 2018 The Origins Of Astronomy and Astrophysics 1. Ancient Astronomy 2. A Spherical Earth 3. The Ptolemaic System 1. Ptolemy's Arrangement 4. Retrograde Motion 1. Epicycles 2. Equants 3. Ptolemaic System 5. Heliocentric 6. Geocentric vs. Heliocentric 7. Positions of Celestial Objects 1. The Altitude-Azimuth Coordinate System 2. The Equatorial Coordinate System 3. Basics of the earth's orbit 4. Celestial equator 8. Solar vs. Sidereal Time 1. Special Times of the year 2. Analemma 9. Equatorial System 10. Time 1. Julian Date 11. Summary 12. Bibliography and Further Reading Ancient Astronomy Fig. 1 A selection of ancient cosmologies. a) Ancient Egyptian Creation myth. The earth is the leaf adorned figure lying down. The sun and moon are riding the boats across the sky. b) Ancient Hebrew Conception of the universe c) Hindu: The earth was on elephants which were on turtles. (And of course a divine cobra) (public domain images) Since the earliest recorded histories, humanity has attempted to explain its position in the universe. Societies and cultures have described many varying pictures of the universe. Often, there would be some deity or certain animals involved that were responsible updated on 2018-08-29 Page 1 PHY 454 - origins-astro - J. Hedberg - 2018 for holding various parts aloft or keeping regions separate or moving things like the sun around the earth. Humans and their civilizations were almost aways located at the center of each universe.Generally there was some sorting to do - put the heavy stuff down there, the light stuff up there. -

On the Pin-And-Slot Device of the Antikythera Mechanism, with a New Application to the Superior Planets*

JHA, xliii (2012) ON THE PIN-AND-SLOT DEVICE OF THE ANTIKYTHERA MECHANISM, WITH A NEW APPLICATION TO THE SUPERIOR PLANETS* CHRISTIÁN C. CARMAN, Universidad Nacional de Quilmes/CONICET, ALAN THORNDIKE, University of Puget Sound, and JAMES EVANS, University of Puget Sound Perhaps the most striking and surprising feature of the Antikythera mechanism uncovered by recent research is the pin-and-slot device for producing the lunar inequality.1 This clever device, completely unattested in the ancient astronomical literature, produces a back-and-forth oscillation that is superimposed on a steady progress in longitude — nonuniform circular motion.2 Remarkably, the resulting motion is equivalent in angle (but not in spatial motion in depth) to the standard deferent-plus-epicycle lunar theory. Freeth et al. gave a proof of this equivalence, which is, however, a very complicated proof.3 One goal of the present paper is to offer a simpler proof that would have been well within the methods of the ancient astronomers and that, moreover, makes clearer the precise relation of the pin-and- slot model to the standard epicycle-plus-concentric and eccentric-circle theories. On the surviving portions of the Antikythera mechanism, only two devices are used to account for inequalities of motion. The first is the pin and slot, used for the lunar inequality. And the second is the nonuniform division of the zodiac scale, which, we have argued, was used to model the solar inequality.4 The second would obviously be of no use in representing planetary inequalities; so a natural question is to ask whether the pin-and-slot mechanism could be modified and extended to the planets, especially to the superior planets, for which the likely mechanical representations are less obvious than they are for the inferior planets. -

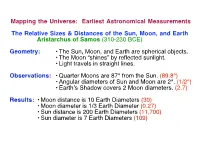

Earliest Astronomical Measurements the Relative

Mapping the Universe: Earliest Astronomical Measurements The Relative Sizes & Distances of the Sun, Moon, and Earth Aristarchus of Samos (310-230 BCE) Geometry: • The Sun, Moon, and Earth are spherical objects. • The Moon “shines” by reflected sunlight. • Light travels in straight lines. Observations: • Quarter Moons are 87° from the Sun. (89.8°) • Angular diameters of Sun and Moon are 2°. (1/2°) • Earth’s Shadow covers 2 Moon diameters. (2.7) Results: • Moon distance is 10 Earth Diameters (30) • Moon diameter is 1/3 Earth Diameter (0.27) • Sun distance is 200 Earth Diameters (11,700) • Sun diameter is 7 Earth Diameters (109) Aristarchus’ Methodology: Step 1: Measurement of Sun-Earth- Quarter Moon angle gives relative Earth-Sun and Earth-Moon distances (a ratio of 20:1*) Step 2: Measurement of Sun and Moon angular diameters gives relative Sun and Earth sizes on the same scale (20:1 again*) * these numbers are low by a factor of almost 20. Step 3: Adjust Earth Diameter to give the correct shadow size at the Moon’s distance. Moon Earth Sun Note that this procedure gives only relative distances and sizes. (See Eratosthenes below.) Note that Aristarchus argued for a heliocentric universe! Earliest Astronomical Measurements (continued) Eratosthenes (276-196 BCE): The Size of the Earth Digression: The Alexandrian Library (300 BCE-300 CE?) Observations • The Well at Syene & the Summer Solstice: α = 0 • The Obelisk at Alexandria: α = 1/50 circle Eratosthenes’ Methodology: Measurement • The Alexandria-Syene distance: 1,592 stadia • This corresponds to 1/50 of the Earth’s circumference Results • Earth Circumference is 1,592 x 50 = 79,600 stadia • Earth Diameter is 79,600 ÷ π = 25,337 stadia Conversion factor: 1 stadium is about 2 kilometers • Earth Diameter is 12,732 kilometers (12, 756 km) Note: Posidinius (135-51 BCE) used “simultaneous” observations of the bright star Canopus in the same way to obtain a size for the Earth. -

Mo on of the Planets on the Celes Al Sphere. the Heliocentric System

Moon of the planets on the celesal sphere. The heliocentric system. The development of the Copernican concept Moon of the planets on the celesal sphere. The heliocentric system. The development of the Copernican concept Scenariusz Lesson plan Moon of the planets on the celesal sphere. The heliocentric system. The development of the Copernican concept Source: licencja: CC 0. Ruch planet na sferze niebieskiej. System heliocentryczny. Rozwój idei kopernikańskiej You will learn to explain the differences between geocentric and heliocentric theory. Nagranie dostępne na portalu epodreczniki.pl nagranie abstraktu Before you start, answer the question. Explain what it means to say about Nicolaus Copernicus that he „stopped the Sun and moved the Earth”. Nagranie dostępne na portalu epodreczniki.pl nagranie abstraktu Our understanding of the Universe has evolved over time. Most of all the early cosmologic models assumed that the Earth was the centre of the Solar System, and not only this, but of the entire Universe. Aristarchus of Samos proposed the first heliocentric model in the third century B.C., but at this time this model did not play an important role. Path of the planet on the background of the stars observed from the Earth Source: GroMar, licencja: CC BY 3.0. Nagranie dostępne na portalu epodreczniki.pl nagranie abstraktu The ancient astronomers observed that planets usually moved east to west against the distant stars, but from time to time they changed the direction and the speed. This motion in the opposite direction was called retrograde motion. Nowadays we know that it is an apparent motion. The Greek astronomer Ptolemy used measurements of the sky to create geocentric model of the Universe. -

Pos(Antikythera & SKA)018

Building the Cosmos in the Antikythera Mechanism Tony Freeth1 Antikythera Mechanism Research Project 10 Hereford Road, South Ealing, London W54 4SE, United Kingdom E-mail: [email protected] PoS(Antikythera & SKA)018 Abstract Ever since its discovery by Greek sponge divers in 1901, the Antikythera Mechanism has inspired fascination and fierce debate. In the early years no-one knew what it was. As a result of a hundred years of research, particularly by Albert Rehm, Derek de Solla Price, Michael Wright and, most recently, by members of the Antikythera Mechanism Research Project, there has been huge progress in understanding this geared astronomical calculating machine. With its astonishing lunar anomaly mechanism, it emerges as a landmark in the history of technology and one of the true wonders of the ancient world. The latest model includes a mechanical representation of the Cosmos that exactly matches an inscription on the back cover of the instrument. We believe that we are now close to the complete machine. From Antikythera to the Square Kilometre Array: Lessons from the Ancients, Kerastari, Greece 12-15 June 2012 1 Speaker Copyright owned by the author(s) under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike Licence. http://pos.sissa.it Building the Cosmos in the Antikythera Mechanism Tony Freeth 1. Ancient Astronomy Astronomy? Impossible to understand and madness to investigate... Sophocles Since astronomy is so difficult, I will try to keep everything as simple as possible! As all astronomers know well, the stars are fixed! When the ancients looked at the sky, they saw a number of astronomical bodies that moved relative to the stars. -

Copernicus and Tycho Brahe

THE NEWTONIAN REVOLUTION – Part One Philosophy 167: Science Before Newton’s Principia Class 2 16th Century Astronomy: Copernicus and Tycho Brahe September 9, 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. The Copernican Revolution .................................................................................................................. 1 A. Ptolemaic Astronomy: e.g. Longitudes of Mars ................................................................... 1 B. A Problem Raised for Philosophy of Science ....................................................................... 2 C. Background: 13 Centuries of Ptolemaic Astronomy ............................................................. 4 D. 15th Century Planetary Astronomy: Regiomantanus ............................................................. 5 E. Nicolaus Copernicus: A Brief Biography .............................................................................. 6 F. Copernicus and Ibn al-Shāţir (d. 1375) ……………………………………………………. 7 G. The Many Different Copernican Revolutions ........................................................................ 9 H. Some Comments on Kuhn’s View of Science ……………………………………………... 10 II. De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelstium (1543) ..................................................................................... 11 A. From Basic Ptolemaic to Basic Copernican ........................................................................... 11 B. A New Result: Relative Orbital Radii ................................................................................... 12 C. Orbital -

A Modern Almagest an Updated Version of Ptolemy’S Model of the Solar System

A Modern Almagest An Updated Version of Ptolemy’s Model of the Solar System Richard Fitzpatrick Professor of Physics The University of Texas at Austin Contents 1 Introduction 5 1.1 Euclid’sElementsandPtolemy’sAlmagest . ......... 5 1.2 Ptolemy’sModeloftheSolarSystem . ..... 5 1.3 Copernicus’sModeloftheSolarSystem . ....... 10 1.4 Kepler’sModeloftheSolarSystem . ..... 11 1.5 PurposeofTreatise .................................. .. 12 2 Spherical Astronomy 15 2.1 CelestialSphere................................... ... 15 2.2 CelestialMotions ................................. .... 15 2.3 CelestialCoordinates .............................. ..... 15 2.4 EclipticCircle .................................... ... 17 2.5 EclipticCoordinates............................... ..... 18 2.6 SignsoftheZodiac ................................. ... 19 2.7 Ecliptic Declinations and Right Ascenesions. ........... 20 2.8 LocalHorizonandMeridian ............................ ... 20 2.9 HorizontalCoordinates.............................. .... 23 2.10 MeridianTransits .................................. ... 24 2.11 Principal Terrestrial Latitude Circles . ......... 25 2.12 EquinoxesandSolstices. ....... 25 2.13 TerrestrialClimes .................................. ... 26 2.14 EclipticAscensions .............................. ...... 27 2.15 AzimuthofEclipticAscensionPoint . .......... 29 2.16 EclipticAltitudeandOrientation. .......... 30 3 Dates 63 3.1 Introduction...................................... .. 63 3.2 Determination of Julian Day Numbers . .... 63 4 Geometric -

Ancient Astronomy: Beginning of Science Laws of Motion

Ancient Astronomy: beginning of science Laws of motion Even in ancient times people were curious to know how everything works around us and how the Universe functions Stonehenge (UK) Medieval China Everything is connected. Athens Ancient Greece Artists, poets, architects, philosophers, scientists, warriors, and statesmen -- ancient greeks made a significant contribution to our human civilization. According to Aristotle, celestial motions are perpetual: there is no reason for those motion to happen; constant motion of celestial objects is natural Ptolemy Fundamental Premises Concerning the Earth and the Cosmos in Greek’s cosmology • The cosmos is a sphere • The Earth is a sphere • The Earth is at the middle of the cosmos • The Earth is motionless Greeks reasoning why Earth is at the center of the Universe Greeks reasoning why Earth is a sphere: the shape of the Earth shadow during lunar eclipses is round. Thus, the shape of the Earth is round too. Parallax is a displacement or difference in the apparent position of an object viewed along two different lines of sight, and is measured by the angle or semi-angle of inclination between those two lines. The term is derived from the Greek παράλλαξις (parallaxis), meaning "alteration". Nearby objects have a larger parallax than more distant objects when observed from different positions, so parallax can be used to determine distances. Astronomers use the principle of parallax to measure distances to celestial objects including to the Moon, the Sun, and to stars beyond the Solar System. (Wikipedia) Parallax and the ancient greeks’ argument why the Earth is in the middle of cosmos. -

Planetary Hypotheses with Introduction and Commentary

Ptolemy’s Planetary Theory: An English Translation of Book One, Part A of the Planetary Hypotheses with Introduction and Commentary by Elizabeth Anne Hamm A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology University of Toronto © Copyright by Elizabeth Anne Hamm, 2011 Abstract Ptolemy’s Planetary Theory: An English Translation of Book One, Part A of the Planetary Hypotheses with Introduction and Commentary Elizabeth A. Hamm Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology University of Toronto 2011 This study comprises a translation and commentary of Book I of the Planetary Hypotheses by the second century A.D. Greco-Roman astronomer, Claudius Ptolemy. It closely examines the Planetary Hypotheses on its own and in relation to Ptolemy’s other writings. Where necessary I rely on astronomical, philosophical, and technological works by other writers in order to better situate Ptolemy’s ideas into the context of Greco- Roman science. The dissertation is organized into three sections. Section I consists of an extended introduction to the Planetary Hypotheses. I offer a synopsis of the Planetary Hypotheses and a history of the text in Sections I.1 and I.2. Section I.3 consists of a brief introduction to notation and sexagesimal numbers while Section I.4 analyzes the aim and function of Ptolemy’s planetary models. Section II is a translation of the existing Greek text of the Planetary Hypotheses, namely Book I Part A, and a précis of Book I, Part B. The translation is made from J.L. -

Classical Quadrivium and Kepler's Harmonice Mundi

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1982 Classical quadrivium and Kepler's Harmonice mundi Stephen Alan Eberhart The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Eberhart, Stephen Alan, "Classical quadrivium and Kepler's Harmonice mundi" (1982). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 1806. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1806 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COPYRIGHT ACT OF 1976 THIS IS AN UNPUBLISHED MANUSCRIPT IN WHICH COPYRIGHT SUB SISTS. ANY FURTHER REPRINTING OF ITS CONTENTS MUST BE APPROVED BY THE AUTHOR. MANSFIELD LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA DATE :1 1 9 8 2 THE CLASSICAL QUADRIVIUM AND KEPLER'S HARMONICE MUNDI by Stephen Alan Eberhart B.M., Oberlin Conservatory of Music, 1961 M.S., University of Washington, 1975 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1982 Approved by s Chairman, Board of Examiners ci //sy - J)ate UMI Number: EP35198 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Astro 210 Lecture 5 Jan 26, 2018 Announcements • HW1 Due

Astro 210 Lecture 5 Jan 26, 2018 Announcements • HW1 due today at 5pm • HW2 available; due in 1 week • register your iClicker; link on course webpage • first Planetarium shows Mon Feb 5 and Wed Feb 7 info online: reservations, schedules, directions, report form • if this is your first class: see me afterward! 1 Last time: planets • paths on celestial sphere are (nearly) great circles stay near ecliptic, in zodiac Q: and so? • motion: mostly eastward w.r.t. celestial sphere, like Sun, Moon • but sometimes retrograde Q: what’s that? • retrograde occurance related to planet angle from Sun Q: how? Today: building scientific models to explain naked-eye sky 2 Cosmological Models: Naked-Eye Sky any viable model must explain all observations including retrograde motion of planets models change: • when predictions fail • when new observations require new explanations model refined → theory theory is end product of model ↔ data not mere speculation or offhand/wacky idea 3 Greek Cosmology Pythagoreans outlook: geometry is everything, perfected in spheres • earth: spherical shape observations of Eratosthenes (276-195 BC) altitude of noonday Sun at solstice: • directly overhead at Syene, Egypt θ ◦ s θ = 7 from vertical at Alexandria θ Q: what do we learn from the R simple fact that the angles differ? • pace off distance s ∼ 800 km ◦ ◦ geometry: s/R = θradians = 2π(7 /360 ) ⇒ R ∼ 6700 km: close! 4 • Moon, Sun, planets, stars fixed on spheres which move in uniform circular motion Geocentrism Ancient Greeks: Earth is center of universe (“geocentric”) ⋆ rise & set of sun/moon/planets can be explained Q: how? ⋆ we don’t feel Earth is spinning would mean we move at 900 mph w.r.t. -

1 Unit 4 Philosophy of Science and Cosmology in The

UNIT 4 PHILOSOPHY OF SCIENCE AND COSMOLOGY IN THE MIDDLE AGES Contents 4.0 Objectives 4.1 Introduction 4.2 Ptolemy’s System 4.3 Planetary Motion and Epicycle 4.4 Post-Ptolemaic Era 4.5 Roger Bacon and Experimental Science 4.6 Let Us Sum Up 4.7 Key Words 4.8 Further Readings and References 4.9 Answers to Check Your Progress 4.0 OBJECTIVES In this unit I propose to deal with three aspects, viz. cosmology, the concept of time and the contribution of Roger Bacon (not to be confused with his more famous namesake Francis Bacon). This unit enables you to understand what happened in Europe after Aristotle. An appraisal of cosmology in middle ages demands that you not only exhibit hindsight, but also far- sightedness while you are traversing through middle ages. This is essential because this particular age exhibited an interplay of three major factors, viz. Aristotelianism, scholasticism and Arabic science which paved the way for Copernican thought after nearly fifteen centuries. Hence the main objective of this unit is to analayse the role played by first two factors in blocking further growth of knowledge for such a long duration. While this is the main theme of this unit, Roger Bacon finds place here because he had the foresight to argue for experimental science. 1 At the end of this unit you must be in a position to identify the change in the mindset of thinkers when compared with philosophers of antiquity. 4.1 INTRODUCTION The Greek civilization till Aristotle’s period is known as Hellenic civilization.