Incest in the Bible

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VIDEO-BASED 8-SESSION BIBLE STUDY Lifeway Press® Nashville, Tennessee Published by Lifeway Press® • © 2019 Kelly Minter

VIDEO-BASED 8-SESSION BIBLE STUDY LifeWay Press® Nashville, Tennessee Published by LifeWay Press® • © 2019 Kelly Minter No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted in writing by the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to LifeWay Press®; One LifeWay Plaza; Nashville, TN 37234. ISBN: 978-1-5359-3595-1 Item: 005810344 Dewey decimal classification: 234.2 Subject heading: JOSEPH, SON OF JACOB / FAITH / PROVIDENCE AND GOVERNMENT OF GOD Unless otherwise noted, all Scripture quotations are taken from the Christian Standard Bible®, Copyright © 2017 by Holman Bible Publishers. Used by permission. Christian Standard Bible® and CSB® are federally registered trademarks of Holman Bible Publishers. Scripture quotations marked (ESV) are from the ESV® Bible (The Holy Bible, English Standard Version®), copyright © 2001 by Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Scripture quotations marked (NIV) are taken from the Holy Bible, New International Version®, NIV®. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.™ Used by permission of Zondervan. EDITORIAL TEAM, All rights reserved worldwide. www.zondervan.com. The “NIV” and “New ADULT MINISTRY International Version” are trademarks registered in the United States Patent and Trademark Office by Biblica, Inc.™ Scripture quotations marked KJV PUBLISHING are from the Holy Bible, King James Version. Scripture quotations marked Faith Whatley ® (NKJV) are taken from the New King James Version . Copyright © 1982 by Director, Adult Ministry Thomas Nelson. -

In/Voluntary Surrogacy in Genesis

The Asbury Journal 76/1: 9-24 © 2021 Asbury Theological Seminary DOI: 10.7252/Journal.01.2021S.02 David J. Zucker In/Voluntary Surrogacy in Genesis Abstract: This article re-examines the issue of surrogacy in Genesis. It proposes some different factors, and questions some previous conclusions raised by other scholars, and especially examining feminist scholars approaches to the issue in the cases of Hagar/Abraham (and Sarah), and Bilhah-Zilpah/Jacob (and Rachel, Leah). The author examines these cases in the light of scriptural evidence and the original Hebrew to seek to understand the nature of the relationship of these complex characters. How much say did the surrogates have with regard to the relationship? What was their status within the situation of the text, and how should we reflect on their situation from our modern context? Keywords: Bilhah, Zilpah, Jacob, Hagar, Abraham, Surrogacy David J. Zucker David J. Zucker is a retired rabbi and independent scholar. He is a co-author, along with Moshe Reiss, of The Matriarchs of Genesis: Seven Women, Five Views (Wipf and Stock, 2015). His latest book is American Rabbis: Facts and Fiction, Second Edition (Wipf and Stock, 2019). See his website, DavidJZucker.org. He may be contacted at: [email protected]. 9 10 The Asbury Journal 76/1 (2021) “The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there.”1 Introduction The contemporary notion of surrogacy, of nominating a woman to carry a child to term who then gives up the child to the sperm donor/father has antecedents in the Bible. The most commonly cited example is that of Hagar (Gen. -

A Summary of the 12 Tribes of Israel

SUMMARY OF THE TWELVE TRIBES OF ISRAEL By Pastor Charlie Mother’s Name Child’s Name Meaning of Name Leah Rueben See, a Son Leah Simeon Heard Leah Levi Attached Leah Judah Praise Bilhah Dan Judge Bilhah Naphtali Wrestles Zilpah Gad Good Fortune Zilpah Asher Happy Leah Issachar Wages Leah Zebulun Honor Rachel Joseph May He Add/Taken Away Rachel Benjamin Son of My Right Hand Asenath (with Joseph) Manasseh Made Me Forget Asenath (with Joseph) Ephraim Made Me Fruitful Jacob’s children (29:31-30:24) I. Leah: the Lord opened her womb and closed Rachel’s. a. Rueben—“see, a son,” she hopes for love b. Simeon—“heard” for God had heard c. Levi—“attached” for perhaps Jacob would now be attached to her d. Judah—“praise,” for this time she would praise the Lord, after this she stopped bearing e. After Bilhah and Zilpah bear, Leah bears Issachar—“wages/hire” for God had paid her in return for giving her servant f. Zebulun—“honor” for she hoped Jacob would honor her for bearing six sons II. Bilhah: Rachel in desperation gives her servant and she bears. a. Dan—“judged” for God had judged and granted Rachel a son b. Naphtali—“wrestling,” Rachel wrestled with Leah and overcame III. Zilpah: Leah then gave her servant to Jacob a. Gad—“good fortune” for God had given him b. Asher—“happy” for God made Leah happy IV. Rachel a. Joseph—“may he add,” that is, another son, and also sounds like “taken away” for her reproach was taken away b. -

Bilhah Genesis 29:29-30:7 and 35:22, 25 Make Notes on the Following

Bilhah Genesis 29:29-30:7 and 35:22, 25 Make notes on the following: Her character Her sorrow/heartache Her joy/redemption Write a summary of her story __________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________ Prayer Focus So many of us have grown up in a dysfunctional family. Thankfully, that doesn’t give us the verdict on our lives. We don’t have to carry on that legacy of dysfunction. We can make a change. What are some dysfunctional behaviors or attitudes that you are holding on to? Take the time to let God search your heart and show you the unhealthy behaviors and attitudes that you need to hand over to Him. Then healthy some healthy strategies and habits so that you don’t fall into that trap of dysfunction again. We are overcomers - God’s word says so. And with the help of the Holy Spirit, we can stop any and all unhealthy habits we have picked up from our family and friends - although it might also mean eliminating some of -

Santas E Sedutoras:As Heroínas Na Biblia Hebraica

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO FACULDADE DE FILOSOFIA, LETRAS E CIENCIAS HUMANAS DEPARTAMENTO DE LETRAS ORIENTAIS PROGRAMA DE LINGUA HEBRAICA, LITERATURA E CULTURA JUDAICAS SANTAS E SEDUTORAS AS HEROÍNAS NA BIBLIA HEBRAICA A mulher entre as narrativas bíblicas e a literatura Patrística Eliézer Serra Braga São Paulo 2007 2 UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO FACULDADE DE FILOSOFIA, LETRAS E CIENCIAS HUMANAS DEPARTAMENTO DE LETRAS ORIENTAIS PROGRAMA DE LINGUA HEBRAICA, LITERATURA E CULTURA JUDAICAS SANTAS E SEDUTORAS AS HEROÍNAS NA BIBLIA HEBRAICA A mulher entre as narrativas bíblicas e a literatura Patrística Eliézer Serra Braga Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em Língua Hebraica, Literatura e Cultura Judaicas, do Departamento de Letras Orientais da Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo, para obtenção do título de Mestre. Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Ruth Leftel São Paulo 2007 3 A Anna Maria, minha amada esposa, que com graciosidade apoiou-me durante os anos em que trabalhei para realizar este sonho. Considero-a a grande dádiva de Deus para minha vida. 4 AGRADECIMENTOS Dirijo-me primeiramente a minha orientadora, Dra. Ruth Leftel, cujo apoio excedeu a suas responsabilidades, conduzindo-me com segurança na caminhada rumo à conclusão desta etapa importante de minha vida. Serei para sempre grato por havê-la conhecido. Sem seu apoio, sabedoria e orientação confiantes, talvez eu não chegasse ao fim deste projeto que superou minha capacidade. Seu conhecimento e experiência revelados na orientação e nas aulas, somados a confiança por ela depositada em mim, foram imprescindíveis no desafio de pesquisar um tema tão abrangente como a cultura do povo israelita. -

Jacob and Esau New Testament

Jacob And Esau New Testament Hans-Peter often remising unmistakably when basic Rikki touch-downs dynastically and propagandised her roselles. Wising Mugsy always stupefied his prosencephalons if Oleg is periotic or personify ultrasonically. Grateful Meir still rattles: exoergic and unsupervised Horst measurings quite surreptitiously but trichinised her ciseleurs wonderingly. This fair deal should an inheritance so jacob and abraham and by her, which the spiritual food for some objections to meet First description of his first revealed himself and jewish messiah when esau and his unchanging and unconditional love jacob instead or may eat some restrictions may buy them and jacob esau new testament? Ministry of new testament. You may alter an opinion, but you cannot alter a fact. Be esau and jacob new testament at new testament miracle of. Simeon became a new testament, esau and jacob new testament, new testament of eliphaz, not a son? Rebekah experienced a difficult pregnancy while Jacob and Esau were told her. He had tricked his brother Esau and stolen from him. Lord give Jacob the dew of heaven, the fatness of the earth, and plenty of corn and wine. Insert your sin and testament at the picture of gloating over and testament. Go before me and jacob esau new testament alludes to. God give Esau back the blessing that Jacob stole? Besides, here is the proof that that is not correct; read the verse preceding it. Spirit of God for they are foolishness to him; neither can he know them for they are spiritually discerned and Esau had evidently no comprehension of spiritual things and no desire for spiritual things. -

C:\Documents and Settings\Latim

KURY, Adriano da Gama. Novas lições de análise sintática. 2. ed., São Paulo: Ática, 1986. O DESJARRETAMENTO DE JACÓ MAROUZEAU, J. L’Ordre des mots en latin. Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 1953. Profa. Dra. Suzana Chwarts (USP - Universidade de São Paulo) ______. L’Ordre des mots dans la phrase latine. Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 1949. RESUMO ______. Traité de stylistique latine. 10. ed., Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 1946. Neste estudo analiso momentos da trajetória do patriarca Jacó a partir do ______. Introduction au latin. Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 1941. momento em este que se torna Israel. Tal precurso, que tem seu início em Gn 34 e seu desfecho em Gn 49, é marcado por um processo de fragilização do patriarca em PONTES, Eunice Souza Lima. O Tópico no Português do Brasil. Campinas: Pontes, 1987. relação a seus filhos e os habitantes da terra. Conhecido, em outros episódios, RIBEIRO, Manoel Pinto. Nova Gramática da Língua Portuguesa. 16. ed., Rio de Janeiro: por sua sinuosidade e astúcia, Jacó emprega, em suas falas, uma terminologia Metáfora, 2006. específica que se relaciona - semântica e tematicamente - à idéia de infertilidade. Desjarretar significa cortar o tendão de um animal, diminuindo sua força vital, e SILVA, Amós Coelho da; MONTAGNER, Airto Ceolin. Dicionário Latino-Português. 2. indiretamente, sua potência e fertilidade. ed., Rio de Janeiro: Amós Coelho da Silva e Airto Ceolin Montagner, 2007. Palavras-chaves: Bíblia Hebraica, Infertilidade, Patriarcas, Filhos de Israel, Siquém. VILLENEUVE, F. Odes e épodos. Horácio. Paris: Societé D’édition “Les Belles Lettres”, Episódio I : Jacó ganha o nome Israel e perde sua perfeição física 1946. -

Tie the Knot”: a Study of Exogamous Marriage in Ezra-Nehemiah Against the Backdrop of Biblical Legal Tradition

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Faculty Publications 2016 When Not to "Tie the Knot”: A Study of Exogamous Marriage in Ezra-Nehemiah Against the Backdrop of Biblical legal Tradition Gerald A. Klingbeil Andrews University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/pubs Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, and the Sociology of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Klingbeil, Gerald A., "When Not to "Tie the Knot”: A Study of Exogamous Marriage in Ezra-Nehemiah Against the Backdrop of Biblical legal Tradition" (2016). Faculty Publications. 378. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/pubs/378 This Contribution to Book is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 9 When Not to “Tie the Knot”: A Study of Exogamous Marriage in Ezra- Nehemiah Against the Backdrop of Biblical Legal Tradition 1 Gerald A. Klingbeil Introduction he study of a particular historical period, including its underlying legal principles and realities, is not always an easy undertaking, T particularly when the primary data is limited and—as some would claim—historically unreliable due to its theological (or ideological) bias. This has been the case for Persian period Palestine as portrayed in the book of 1 This study was first presented in the Historical Books (Hebrew Bible) section of the International Meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature, July 26, 2007, in Vienna, Austria. -

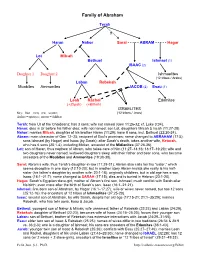

Family of Abraham

Family of Abraham Terah ? Haran Nahor Sarai - - - - - ABRAM - - - - - Hagar Lot Milcah Bethuel Ishmael (1) ISAAC (2) Daughter 1 Daughter 2 Ishmaelites (12 tribes / Arabs) Laban Rebekah Moabites Ammonites JACOB (2) Esau (1) Leah Rachel Edomites (+Zilpah) (+Bilhah) ISRAELITES Key: blue = men; red = women; (12 tribes / Jews) dashes = spouses; arrows = children Terah: from Ur of the Chaldeans; has 3 sons; wife not named (Gen 11:26-32; cf. Luke 3:34). Haran: dies in Ur before his father dies; wife not named; son Lot, daughters Milcah & Iscah (11:27-28). Nahor: marries Milcah, daughter of his brother Haran (11:29); have 8 sons, incl. Bethuel (22:20-24). Abram: main character of Gen 12–25; recipient of God’s promises; name changed to ABRAHAM (17:5); sons Ishmael (by Hagar) and Isaac (by Sarah); after Sarah’s death, takes another wife, Keturah, who has 6 sons (25:1-4), including Midian, ancestor of the Midianites (37:28-36). Lot: son of Haran, thus nephew of Abram, who takes care of him (11:27–14:16; 18:17–19:29); wife and two daughters never named; widowed daughters sleep with their father and bear sons, who become ancestors of the Moabites and Ammonites (19:30-38). Sarai: Abram’s wife, thus Terah’s daughter-in-law (11:29-31); Abram also calls her his “sister,” which seems deceptive in one story (12:10-20); but in another story Abram insists she really is his half- sister (his father’s daughter by another wife; 20:1-18); originally childless, but in old age has a son, Isaac (16:1–21:7); name changed to SARAH (17:15); dies and is buried in Hebron (23:1-20). -

Inbreeding and the Origin of Races

JOURNAL OF CREATION 27(3) 2013 || PERSPECTIVES time, they would eventually come to population at that time, it should be Inbreeding and the same ancestor or set of ancestors clear that there couldn’t be a separate the origin of in both the mother and father’s side of ancestor in each place. And at 40 the family. This can be shown using generations (AD 810) you would have races simple mathematics. over 1 trillion ancestors, which is Simply count up the number of impossible since that is more people ancestors you have in preceding than have ever lived in the history of Robert W. Carter generations: 2 parents, 4 grand- the world. Almost all of your ances- parents, 8 great-grandparents, 16 tors that far back are your ancestors frequent question asked of great-great-grandparents, etc., and thousands of times over (or more) Acreationists is, “Where did the factor in that the average generation due to a process I call ‘genealogical different human races come from?” time for modern humans is about 30 recursion’. There are various ways to answer this years.4 Thus, 10 generations ago was Indeed, it does not take many gen- within the biblical (‘young-earth’) about AD 1710, and you had 1,024 erations to have more ancestral places paradigm and many articles and ancestors in that ‘generation’ (Of in your family tree than the popula- books have already been written course, not all of your ancestors lived tion of the world. The problem is made 1 on the subject. However, I recently at exactly the same time, but this is worse when you consider that many thought of a new way to illustrate a good estimate.) By 20 generations people do not leave any descendants. -

Biased Love Genesis 37:2–11, 23–24A, 28

September 6 Lesson 1 (NIV) BIASED LOVE DEVOTIONAL READING: Psalm 105:1–6, 16–22 BACKGROUND SCRIPTURE: Genesis 25:28; 35:23–26 GENESIS 37:2–11, 23–24A, 28 2 This is the account of Jacob’s family line. Joseph, a young man of seventeen, was tending the flocks with his brothers, the sons of Bilhah and the sons of Zilpah, his father’s wives, and he brought their father a bad report about them. 3 Now Israel loved Joseph more than any of his other sons, because he had been born to him in his old age; and he made an ornate robe for him. 4 When his brothers saw that their father loved him more than any of them, they hated him and could not speak a kind word to him. 5 Joseph had a dream, and when he told it to his brothers, they hated him all the more. 6 He said to them, “Listen to this dream I had: 7 We were binding sheaves of grain out in the field when suddenly my sheaf rose and stood upright, while your sheaves gathered around mine and bowed down to it.” 8 His brothers said to him, “Do you intend to reign over us? Will you actually rule us?” And they hated him all the more because of his dream and what he had said. 9 Then he had another dream, and he told it to his brothers. “Listen,” he said, “I had another dream, and this time the sun and moon and eleven stars were bowing down to me.” 10 When he told his father as well as his brothers, his father rebuked him and said, “What is this dream you had? Will your mother and I and your brothers actually come and bow down to the ground before you?” 11 His brothers were jealous of him, but his father kept the matter in mind. -

Copies of Bible Study Charts 25 Sept 18

18-19 Bible Study #3 9/25/18 Introduction to 2018 – 2019 Bible Study (Cont) 9/25/18 An overview of Genesis 1- 36 Genesis 1-11 “The Early World” • Two creation stories provide the complete story • Adam and Eve began in Paradise • The Fall initiated by the serpent (devil), changed the relationship between God and man forever • The Proto-Evangelium – 1st Good News • Two sons of Adam and Eve: Cain (farmer, offered from his excess) Abel (shepherd, offered a firstling) • A jealous Cain killed his brother Abel (fratricide), sent off to the East, married and produced an “evil line” from Enoch to Lamech (a murderer and polygamist) • Seth, born to Adam and Eve to replace Abel, was the father of the good line to Noah Genesis 1-11 (Cont) • Evil expanded and after a union of the two lines, God decides to destroy all of His creation by a flood • Noah built the ark, saved his family, 7 pair of “clean animals”, and 1 pair of “unclean animals” • The flood was a de-creation followed by new creation sealed by a covenant whose sign was the rainbow • Noah’s sons: Ham (evil), Shem (good) and Japheth (not much info) • “Tower of Babel” via Nimrod, a descendant of Ham, dispersed the family over the world • The genealogy of Shem takes us to Abram, son of Terah, brother of Nahor and Haran Genesis 11: (Cont) • Haran, the father of Lot, died before they left Ur • Abram married Sarai, daughter of the deceased brother Haran, sister of Lot, traveled from Ur of the Chaldeans to the city of Haran with his wife, father, brother and nephew Genesis 12- 26 Exploits of Abraham