Metatarsalgia: Distal Metatarsal Osteotomies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chief Complaint

Chief Complaint Please choose the primary reason you are coming to our office. Complaints are listed alphabetically. Please do not select more than 5 complaints. Upper Back: Thigh/Hip: Calf: o Asthma o Arterial insufficiency o Left calf pain o Bronchitis o Left hip pain o Left leg cramps o Emphysema o Left hip tendonitis o Left leg numbness o Left Flank Pain o Left leg cramps o Left leg pain o Midback pain o Left leg numbness o Left leg weakness o Left leg pain o Leg cramps Lower Back: o Left leg weakness o Leg numbness o Fatigue o Left post. thigh pain o Leg weakness o Left flank pain o Left thigh pain o Varicose veins o Low back pain o Sciatica o Venous insufficiency o Low back spasm o Venous insufficiency o Arterial insufficiency o Lumbar arthritis o Right hip pain o Right calf pain o Menstrual cramps o Right hip tendonitis Right leg o Right leg cramps o Nervousness cramps o Right leg numbness o Pain during BM o Right leg numbness o Right leg pain o Right flank pain o Right leg pain o Right leg weakness o Sacroiliac pain o Right leg weakness o Sciatica o Right post. thigh pain Neck: o Stiffness o Right thigh pain o Bronchitis o Whole body pain o Clavicular pain Head: Buttocks: o Cold o Agitation o Bleeding during BM o Coughing o Anxiety attack o Bursitis of hip o Dysphagia o Cold o Gluteal pain o Goiter o Diminished concentration o Hemorrhoids o Hoarseness o Dizziness o Left gluteal pain o Neck pain o Dysphagia o Left hip pain o Neck spasm o Ear pain o Left post. -

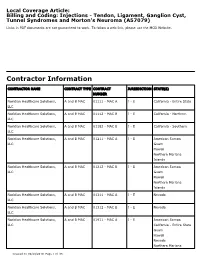

Billing and Coding: Injections - Tendon, Ligament, Ganglion Cyst, Tunnel Syndromes and Morton's Neuroma (A57079)

Local Coverage Article: Billing and Coding: Injections - Tendon, Ligament, Ganglion Cyst, Tunnel Syndromes and Morton's Neuroma (A57079) Links in PDF documents are not guaranteed to work. To follow a web link, please use the MCD Website. Contractor Information CONTRACTOR NAME CONTRACT TYPE CONTRACT JURISDICTION STATE(S) NUMBER Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01111 - MAC A J - E California - Entire State LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01112 - MAC B J - E California - Northern LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01182 - MAC B J - E California - Southern LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01211 - MAC A J - E American Samoa LLC Guam Hawaii Northern Mariana Islands Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01212 - MAC B J - E American Samoa LLC Guam Hawaii Northern Mariana Islands Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01311 - MAC A J - E Nevada LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01312 - MAC B J - E Nevada LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01911 - MAC A J - E American Samoa LLC California - Entire State Guam Hawaii Nevada Northern Mariana Created on 09/28/2019. Page 1 of 33 CONTRACTOR NAME CONTRACT TYPE CONTRACT JURISDICTION STATE(S) NUMBER Islands Article Information General Information Original Effective Date 10/01/2019 Article ID Revision Effective Date A57079 N/A Article Title Revision Ending Date Billing and Coding: Injections - Tendon, Ligament, N/A Ganglion Cyst, Tunnel Syndromes and Morton's Neuroma Retirement Date N/A Article Type Billing and Coding AMA CPT / ADA CDT / AHA NUBC Copyright Statement CPT codes, descriptions and other data only are copyright 2018 American Medical Association. -

Clinical Guidelines: Foot / Ankle

Clinical Guidelines: Foot / Ankle Plantar Fasciitis/Heel spurs: Initial Evaluation: History includes usually atraumatic plantar medial heel pain, worst first thing in the morning or after prolonged sitting. Exam includes tenderness with deep palpation of the plantar medial heel. Squeezing the heel bone side to side is NOT tender, but if present could represent a calcaneal stress fracture. X-rays may or may not reveal a heel spur, but the spur is NOT the source of the pain despite podiatry frequently referring to this as “heel spur syndrome.” Follow-up: The plantar fascia is the soft tissue under our foot that runs from the heel to the toes, much like the palm of our hand; it is the sole of our foot. The plantar fascia stretch includes crossing your legs and dorsiflexing the ankle and stretching the toes into extension. This is the most effective stretch. A night splint is imperative for improvement and should be used at night for 6 weeks. Cortisone injections and physical therapy can be helpful. NSAIDS and a frozen water bottle rolled on the plantar foot could be used with the above treatment, but the most effective treatment is a night splint. Referral: 90% of heel pain resolves with non-op treatment, but make a referral to a foot / ankle ortho surgeon with any atypical heel pain or failure of 6-8 weeks of non-operative treatment. Atypical heel pain usually gets an MRI, but classic plantar fasciitis does not. Bunion (hallux valgus): Initial Treatment: Bunion deformity includes a bump on the medial side of the big toe, the big toe going the wrong way, and a widened forefoot. -

Metatarsalgia

Metatarsalgia Definition Metatarsalgia is a generic term for pain or discomfort in the sole of the forefoot (the ball of the foot). It is an inflammatory condition of the metatarsal heads due to a drop or collapse of the metatarsal arch. The arch flattens and the bone ends (metatarsal heads) move closer together causing the soft tissue to be pinched or trapped between the bones. With every step, the arch rises and falls causing repeated stress to the area. More specific type of Metatarsalgia can be: • Morton’s Neuroma ( nerve issue) • Bursitis • Arthritic joint change • Stress Fractures Symptoms • Vague pain, ache or burning in the sole of the forefoot, during weight-bearing activities • Tingling / numbness in toes • Sharp or shooting pain in toes • Aggravated when dorsi-flexing (lifting) toes • Callousing under 2nd, 3rd and 4th toes • Feeling of “walking on pebbles” Causes Anything that puts extra stress on the forefoot can cause Metatarsalgia. Common examples are: • Use of improper footwear (i.e. high-heeled shoes and boots) • High-arched or “cavus” foot or flat arch feet “pes planus” which causes the bones in the front of the foot (metatarsals) to point down into the sole to an excessive extent, or a long metatarsal bone which takes extra pressure • Claw or hammer toes which press the metatarsals down towards the ground • A nerve problem near the 3rd and 4th toes • A stretched or irritated nerve in the ball of the foot (inter-digital neuroma) or behind the ankle (tarsal tunnel syndrome) can produce pain in the ball of the foot • A bunion or arthritis in the big toe can weaken the big toe and throw extra stress onto the ball of the foot. -

Chronic Foot Pain

Revised 2020 American College of Radiology ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Chronic Foot Pain Variant 1: Chronic foot pain. Unknown etiology. Initial imaging. Procedure Appropriateness Category Relative Radiation Level Radiography foot Usually Appropriate ☢ US foot Usually Not Appropriate O MRI foot without and with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate O MRI foot without IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate O CT foot with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢ CT foot without and with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢ CT foot without IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢ Bone scan foot Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢ Variant 2: Persistent posttraumatic foot pain. Radiographs negative or equivocal. Clinical concern includes complex regional pain syndrome type I. Next imaging study. Procedure Appropriateness Category Relative Radiation Level MRI foot without IV contrast Usually Appropriate O 3-phase bone scan foot Usually Appropriate ☢☢☢ MRI foot without and with IV contrast May Be Appropriate O US foot Usually Not Appropriate O CT foot with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢ CT foot without and with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢ CT foot without IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢ Variant 3: Chronic metatarsalgia including plantar great toe pain. Radiographs negative or equivocal. Clinical concern includes sesamoiditis, Morton’s neuroma, intermetatarsal bursitis, chronic plantar plate injury, or Freiberg’s infraction. Next imaging study. Procedure Appropriateness Category Relative Radiation Level MRI foot without IV contrast Usually Appropriate O US foot May Be Appropriate O MRI foot without and with IV contrast May Be Appropriate O CT foot without IV contrast May Be Appropriate ☢ Bone scan foot May Be Appropriate ☢☢☢ CT foot with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢ CT foot without and with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢ ACR Appropriateness Criteria® 1 Chronic Foot Pain Variant 4: Chronic plantar heel pain. -

These Feet Won't Walk! What's Next?

2/1/2018 THESE FEET WON’T KARRIE LYNN CROSBY, WALK! WHAT’S NEXT? MPAS, PA-C OBJECTIVE DISCUSS DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT OF COMMON FOOT AND ANKLE PROBLEMS PLANTAR FASCIITIS 1 2/1/2018 PLANTAR FASCIITIS DIAGNOSIS/HISTORY: .FIRST STEP OR AM PAIN .RECENT SHOE GEAR CHANGE .STAND FOR LONG PERIODS OF TIME .WHAT TYPE OF FLOORING DO THEY HAVE OR STAND ON? .BAREFOOT .PLANTAR FASCIA PAIN ON PALPATION, TIGHT GASTROCS .NO OTHER DIAGNOSIS SUPPORTED ON XRAYS PLANTAR FASCIITIS TREATMENT: . AVOID GOING BAREFOOT . SHOE GEAR CHANGE . DON’T WEAR SAME PAIR OF SHOES MORE THEN 1 DAY . DON’T WEAR SHOES FOR MORE THEN 500 MILES . WONDERZORB HEEL PADS (CUSTOM ACCOMMODATIVE ORTHOTICS) . ICING . MASSAGE PLANTAR FASCIA BEFORE GETTING OUT OF BED PLANTAR FASCIITIS TREATMENT CONTINUED… .GASTROC/SOLEUS STRETCHING .TOPICAL NSAIDS .ORAL NSAIDS .STEROID DOSEPACK .BOOT (NIGHT SPLINTS) .SURGERY- GASTROC SLIDE, TOPAZ PROCEDURE 2 2/1/2018 PLANTAR FASCIITIS HAGLUND’S DEFORMITY ACHILLES TENDONITIS DIAGNOSIS/HISTORY: . OVERUSE . CONCENTRIC EXERCISES LIKE TOE RAISES OR SIMILAR . SHOES THAT HAVE A SEAM OR SHARP HEEL COUNTER . TIGHT GASTROCS . BODY MECHANICS . XRAYS- CALCIFICATIONS IN ACHILLES OR HAGLUND’S DEFORMITY . IF TEAR IS SUSPECT ORDER MRI . THOMPSON TESTING 3 2/1/2018 ACHILLES TENDONITIS TREATMENT: .BOOT OR SHOE WITH HEEL LIFT, REST .ICING .PHYSICAL THERAPY (GASTROC/SOLEUS STRETCH) ECCENTRIC STRETCHING .ULTRASOUND .SHOE GEAR MODIFICATION .NEVER INJECT WITH STEROIDS- RISK OF ACHILLES RUPTURE GASTROCNEMIUS ACHILLES TENDONITIS TREATMENT CONTINUED… .ORAL &/0R TOPICAL NSAIDS, ORAL STEROIDS .WARN ABOUT RECURRANCE OF PAIN AND RESTARTING BEHAVIOR MODIFICATIONS EARLY .SURGERY- GASTROC SLIDE, TOPAZ PROCEDURE, ACHILLES TENDON REPAIR 4 2/1/2018 MORTON’S FOOT TYPE METATARSALGIA DIAGNOSIS/HISTORY: .PLANTAR METATARSAL PAIN .OVERUSE, ACTIVITIES THAT PUT AREA UNDER STRESS .POOR SHOE GEAR OR POOR FIT .NO SIGN OF FRACTURE ON PLAIN FILMS .PREVIOUS STEROID INJECTION AROUND THE REGION IF THE SHOE FITS, WEAR IT 5 2/1/2018 METATARSALGIA TREATMENT: . -

Orthosports Orthopaedic Update 2012

2012 LATEST ORTHOPAEDIC UPDATES 47-49 Burwood Rd Lvl 3, 29-31 Dora Street Lvl 3, 1a Barber Ave 160 Belmore Rd CONCORD NSW 2137 HURSTVILLE NSW 2220 KINGSWOOD NSW 2747 RANDWICK NSW 2031 Tel: 02 9744 2666 Tel: 02 9580 6066 Tel: 02 4721 1865 Tel: 02 9399 5333 Fax: 02 9744 3706 Fax: 02 9580 0890 Fax: 02 4721 2832 Fax: 02 9398 8673 www.orthosports.com.au Doctors Consulting here Dr Mel Cusi Dr David Dilley 47-49 Burwood Road Tel 02 9744 2666 Dr Todd Gothelf Concord CONCORD NSW 2137 Fax 02 9744 3706 Dr George Konidaris Dr John Negrine Dr Rodney Pattinson Dr Doron Sher Dr Kwan Yeoh Doctors Consulting here Dr Paul Annett Dr Mel Cusi Dr Jerome Goldberg Suite F-Level 3 Tel 02 9580 6066 Dr Todd Gothelf Hurstville Medica Centre Fax 02 9580 0890 Dr George Konidaris 29-31 Dora Street Dr Andreas Loefler HURSTVILLE NSW 2220 Dr John Negrine Dr Rodney Pattinson Dr Ivan Popoff Dr Allen Turnbull Dr Kwan Yeoh Level 3 Doctors Consulting here Tel 4721 1865 Penrith 1a Barber Avenue Dr Todd Gothelf Fax 4721 2832 KINGSWOOD NSW 2747 Dr Kwan Yeoh Doctors Consulting here Dr John Best Dr Mel Cusi Dr Jerome Goldberg 160 Belmore Road Tel 02 9399 5333 Dr Todd Gothelf Randwick RANDWICK NSW 2031 Fax 02 9398 8673 Dr Andreas Loefler Dr John Negrine Dr Rodney Pattinson Dr Ivan Popoff Dr Doron Sher Dr Kwan Yeoh www.orthosports.com.au Thank you for attending our Latest Orthopaedic Updates Lecture. All of the presentations and handouts are available for viewing on the Teaching Section of our website: www.orthosports.com.au We would love your feedback – Tell us what you liked about the day and what you think we could improve for next year. -

Common Forefoot Conditions Mr Nadeem Mushtaq

Common Forefoot Conditions What can I do in the Primary Care Setting & when to Refer? Mr Nadeem Mushtaq Department of Trauma & Orthopaedics Contact Mr Nadeem Mushtaq Consultant Trauma & Orthopaedic Surgeon Imperial College Healthcare, London Head of Foot & Ankle and Trauma . St Mary’s Hospital, Paddington . The Lindo Wing – St. Mary’s Paddington . The Hospital of St. John & St. Elizabeth . The Bupa Cromwell NHS Secretary Private Secretary tel: 02078673747 [email protected] email: [email protected] Aims Todays topics Understanding the Foot Hallux valgus Hallux rigidus Morton’s Neuroma Plantar Fasciitis Friedberg’s Disease Lesser Toe Disorders Introduction . 26 Bones (+ sesamoids & accessory) . Joints . Muscles . Tendons . Function . Weight - standing / walking / running Hallux valgus ( not bunion) • Hallux valgus • is lateral deviation of the big toe at 1st MTPJ • BUT – is that all •? clinical • 9:1 female : male • 15:1 shoes : barefoot • 23% in aged 18-65 years (CI: 16.3 to 29.6) • 35.7% in aged over 65 years (CI: 29.5 to 42.0) • Prevalence increases with age and is higher in females Causes . genetic predisposition with an imbalance of intrinsic and extrinsic forces on the joint. Instability in the MTPJ or TMT joint combined with tight footwear results in the classical deformity which over time becomes fixed and painful. Medical conditions may also predispose to developing the condition (Table 1). Medical conditions predisposing Gout Rheumatoid arthritis Psoriatic arthropathy Joint hypermobility Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Marfan's syndrome ligamentous laxity Down's syndrome Multiple sclerosis Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease Cerebral palsy Presentation: usually due to pain . pain over the bunion (bursa pain) . -

Everything You Need to Know About Metatarsalgia

EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT METATARSALGIA METATARSALGIA If you participate in activities that involve running and jumping, you can get a condition in which the ball of your foot becomes painful and inflamed. This is called metatarsalgia. It is also caused by foot deformities and shoes that are ill-fitting. Symptoms of metatarsalgia can include sharp, aching, or burning pain in the ball of your foot, pain that worsens when you stand, run, flex your feet or walk, sharp or shooting pain, numbness, or tingling in your toes, or the feeling of having a pebble in your shoe. Metatarsalgia is the pain and inflammation caused by injury to the ball of the foot. Although metatarsalgia is thought of as a symptom of other conditions rather than a specific disease, it is still considered a common overuse injury. ANATOMY & DESCRIPTION ANATOMY Metatarsalgia, a forefoot injury, can occur in anyone, though athletes who participate in intense sports involving running or jumping are at the highest risk. Metatarsalgia occurs when there is intense or unusual pressure on the ball of the foot, creating pain and inflammation. DESCRIPTION Metatarsalgia can be caused by injury during a sport or physical activity. If there is an abnormal weight distribution or unusual movement, the foot is more susceptible. Metatarsalgia pain generally occurs over time rather than immediately and can last several months with increasing severity. Fibula Tibia Talus Navicular Cuboid Cuneiform Metatarsal Calcaneus Phalange BONES OF THE FOOT METATARSALGIA SYMPTOMS Symptoms of metatarsalgia include irritation and inflammation of the ball of the foot and pain at the end of one or more of the metatarsal bones. -

Equinus Deformity in the Pediatric Patient: Causes, Evaluation, and Management

Equinus Deformity in the Pediatric Patient: Causes, Evaluation, and Management a,b,c Monique C. Gourdine-Shaw, DPM, LCDR, MSC, USN , c, c Bradley M. Lamm, DPM *, John E. Herzenberg, MD, FRCSC , d,e Anil Bhave, PT KEYWORDS Equinus Pediatric External fixation Achilles tendon lengthening Gastrocnemius recession Tendo-Achillis lengthening Different body and limb segments grow at different rates, inducing varying muscle tensions during growth.1 In addition, boys and girls grow at different rates.1 The rate of growth for girls spikes at ages 5, 7, 10, and 13 years.1 The estrogen-induced pubertal growth spurt in girls is one of the earliest manifestations of puberty. Growth of the legs and feet accelerates first, so that many girls have longer legs in proportion to their torso during the first year of puberty. The overall rate of growth tends to reach a peak velocity (as much as 7.5 to 10 cm) midway between thelarche and menarche and declines by the time menarche occurs.1 In the 2 years after menarche, most girls grow approximately 5 cm before growth ceases at maximal adult height.1 The rate of growth for boys spikes at ages 6, 11, and 14 years.1 Compared with girls’ early growth spurt, growth accelerates more slowly in boys and lasts longer, resulting in taller adult stature among men than women (on average, approximately 10 cm).1 The difference is attributed to the much greater potency of estradiol compared with testosterone in Two authors (BML and JEH) host an international teaching conference supported by Smith & Nephew. -

Imaging of Central Metatarsalgia

rad review of skeletal imaging and bone densitometry Imaging of central metatarsalgia RAD Magazine, 45, 528, 29-30 Dr Ayesha Niaz Consultant radiologist Dr Akash Ganguly Consultant radiologist Dr Hifz Aniq Consultant radiologist Royal Liverpool University Hospital A Metatarsalgia refers to a variety of disorders presenting with forefoot pain ranging from traumatic lesions (acute or chronic repetitive), inflammatory and infective disorders, non-neoplastic soft tissue lesions, and benign tumours to malignant lesions. Patients often present with symptoms of localised pain in the forefoot that worsens on weight bearing (walking or running), which can be sharp or dull and can be perceived as a lump felt inside or underneath the foot and described as walking on a marble or pebbles. Such patients are labelled as having metatarsalgia and further evaluated with ultrasound or MRI to establish a diagnosis. We describe imaging features of commonly occurring conditions that pro- duce central metatarsalgia. B Morton’s neuromas are masses composed of perineural fibrosis and nerve degeneration as a result of compression of the interdigital nerve against the deep transverse inter- metatarsal ligament. The most common clinical symptom is localised pain in the forefoot. Pain is worse on weight bear- ing, classically described as walking on a marble and can be associated with numbness and tingling.1 They appear as a peanut- or dumbbell-shaped nodule at the level of the metatarsal head, projecting plantar to the deep transverse intermetatarsal ligament on coronal images.2 Morton’s neuroma appears iso- to mildly hyperintense on C T1-weighted MR images and iso- to hypointense on T2- weighted MR images. -

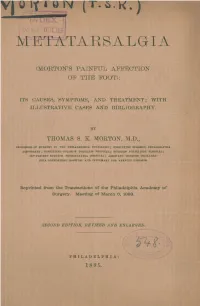

Metatarsalgia (Morton's Painful Affection of the Foot)

METATAESALGIA (MORTON’S PAINFUL AFFECTION OF THE FOOT): ITS CAUSES, SYMPTOMS, AND TREATMENT; WITH ILLUSTRATIVE CASES AND BIBLIOGRAPHY. BY THOMAS S. K MORTON, M.D., PROFESSOR OF SURGERY IN THE PHILADELPHIA POLYCLINIC; CONSULTING SURGEON PHILADELPHIA DISPENSARY; CONSULTING SURGEON DOUGLASS HOSPITAL; SURGEON POLYCLINIC HOSPITAL; OUT-PATIENT SURGEON PENNSYLVANIA HOSPITAL; ASSISTANT SURGEON PHILADEL- PHIA ORTHOPEDIC HOSPITAL AND INFIRMARY FOB NERVOUS DISEASES. Reprinted from the Transactions of the Philadelphia Academy of Surgery. Meeting of March 0, 1893. SECOND EDITION, REVISED AND ENLARGED. PHILADELPHIA: 1895. NOTE Although a large number of copies of the original reprint of this brochure was at my disposal, yet the last one has been called for and sent away, while requests from almost every part of the country for it or litera- ture of the subject continue to reach me in increasing frequency. Hence I have determined to print this second edition of the pamphlet for those who may desire it, and at the same time take advantage of the opportunity afforded to record some additional observations and ex- periences and to bring the bibliography up to the present time. T. S. K. M. December, 1895. MET ATAE SALGTA The affection that has come to be best known as “ Morton’s Painful Affection of the Foot,” or “ Morton’s Toe,” was first described and a method of certain cure presented by Dr. Thomas G. Morton, of Philadelphia, in 1876, under title of “ A Peculiar Painful Affection of the Fourth Metatarso- phalangeal Articulation..”* In subsequent publicationsf he has confirmed his views relative to cause and treatment, and reported large numbers of cases.