A Development Model with Tibetan Characteristics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Little Tibet” with “Little Mecca”: Religion, Ethnicity and Social Change on the Sino-Tibetan Borderland (China)

“LITTLE TIBET” WITH “LITTLE MECCA”: RELIGION, ETHNICITY AND SOCIAL CHANGE ON THE SINO-TIBETAN BORDERLAND (CHINA) A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Yinong Zhang August 2009 © 2009 Yinong Zhang “LITTLE TIBET” WITH “LITTLE MECCA”: RELIGION, ETHNICITY AND SOCIAL CHANGE ON THE SINO-TIBETAN BORDERLAND (CHINA) Yinong Zhang, Ph. D. Cornell University 2009 This dissertation examines the complexity of religious and ethnic diversity in the context of contemporary China. Based on my two years of ethnographic fieldwork in Taktsang Lhamo (Ch: Langmusi) of southern Gansu province, I investigate the ethnic and religious revival since the Chinese political relaxation in the 1980s in two local communities: one is the salient Tibetan Buddhist revival represented by the rebuilding of the local monastery, the revitalization of religious and folk ceremonies, and the rising attention from the tourists; the other is the almost invisible Islamic revival among the Chinese Muslims (Hui) who have inhabited in this Tibetan land for centuries. Distinctive when compared to their Tibetan counterpart, the most noticeable phenomenon in the local Hui revival is a revitalization of Hui entrepreneurship, which is represented by the dominant Hui restaurants, shops, hotels, and bus lines. As I show in my dissertation both the Tibetan monastic ceremonies and Hui entrepreneurship are the intrinsic part of local ethnoreligious revival. Moreover these seemingly unrelated phenomena are in fact closely related and reflect the modern Chinese nation-building as well as the influences from an increasingly globalized and government directed Chinese market. -

Sichuan/Gansu/Qinghai/Tibet (14 Days) We Love Road Journeys

Tibetan Highlands: Sichuan/Gansu/Qinghai/Tibet (14 Days) We love road journeys. They are by far our favourite way of traveling. We think the world of western China and the countries that border on this region – think Vietnam, Lao, Thailand, Myanmar, for example. On the Road Experiences is all about sharing with like-minded travelers just how beautiful a road journey in these varied lands can be. Now turn the page to find out what we’ve come to love so much… p2 p3 Itinerary Map …where you will travel… p. 006 Yes, it is possible… p. 008 Journey of Discovery… p. 010 Day-by-day… p. 056 In closing... Any car you like, so long as it is an SUV… p. 077 Adventures and discoveries in local cuisines p. 078 What’s included/Best Months to Go... p. 080 Photo credits p. 083 p5 Itinerary Map Day1 Day8 Arrival in Chengdu – Dulan to Golmud – Apply for your temporary driving Across the Qaidam Basin to Golmud license and visit Chengdu’s beautiful Panda Reserve Day9 Golmud to Tuotuohe – Day2 Up, up, up - Onto the Plateau and Chengdu to Maerkang – into the highlands of Qinghai Through the valleys to the Gyarong Tibetan region Day10 Tuotuohe to Naqu – Day3 Cross the famous Tanggula Pass on Maerkang to Ruoergai – your way to Tibet itself Towards the very north of Sichuan on the way to Gansu Day11 Naqu to Damxung – Day4 Visit one of Tibet’s holiest lakes, Ruoergai to Xiahe – Lake Nam-tso Your first and only stop in Gansu province Day12 Damxung to Lhasa – Day5 Complete your journey with Xiahe to Qinghai’s capital, Xining – a beautiful drive to your final On your way to Qinghai destination Day6 Day13 Xining – In and around Lhasa – Spend a day in and around Xining for Visit Potala Palace and explore the a bit of rest and visit the spectacular old city of Lhasa Ta’er Monastery Day14 Day7 Depart from Lhasa – Xining to Dulan – Lift must go on...Farewell Lhasa On the way to Golmud.. -

Silk Road, NW China Joseph Rollason

Alumni Grant 2016-17 Silk Road, NW China Joseph Rollason Joseph Rollason (2016 cohort) received an Alumni Grant funded by the TTS Foundation. During his gap year, Joseph had set himself the challenge to learn Chinese and live in China. He lived in Shanghai with a Chinese family, attending a state university and travelling with Chinese friends within the east and north-east of the country. He explored the Chinese section of the Silk Road in order better to understand minority culture as well as Chinese economic development and its 'One Belt, One Road' project in particular. Funding was earned through working at a hotel in Galle, Sri Lanka as well as teaching English in Shanghai. Click here to view Instagram. I set out to travel on land from Shanghai to Xinjiang province - the northwestern corner of China. This route takes you along the old Silk Road, an historic trading route, as well as through some of the most ethnically and culturally diverse areas of the country. I was particularly interested in the Uighur ethnicity in Xinjiang province, due to ongoing tensions and conflict with the government over their unique cultural identity and the CCP's aggressive reaction to it. However, the route also sees Tibetans, Hui, Tajiks, Russians and Mongols, as well as the enormous variety within these groups. I hoped that seeing these unique Chinese minority cultures and the local government surrounding them would provide greater context to better understand the fascinatingly complex country I was living in. Typical of my experiences of travel in China, things didn't go to plan. -

From the Tribe to the Settlement - Human Mechanism of Tibetan Colony Formation

2013 International Conference on Advances in Social Science, Humanities, and Management (ASSHM 2013) From the tribe to the settlement - human mechanism of Tibetan colony formation - In Case Luqu Gannan Lucang Wang1 Rongwie Wu2 1College of Geography and Environment, Northwest Normal University Lanzhou, China 2College of Geography and Environment, Northwest Normal University Lanzhou, China Abstract layout. Gallin (1974) obtained that there was a close relationship between the rural residential location of Tribal system and the regime has a long history in Luqu agglomeration and central tendency and reforment of County. Tribal system laid the tribal jurisdiction, which is government public infrastructure by the model analysis[4]. the basis for the formation of village range; and hierarchy Although settlements have the close relationship with the of the tribe also determines the level of village system and natural environment, human factors are increasing in the the hierarchical size structure of village; Tribal economic development of the role of them[5]. Zhang (2004) puts base impacted the settlement spatial organization. With forward the “city-town-settlement”which is a settlement consanguinity and kinship as a basis, tribal laid the hierarchy on the basis of Su Bingqi’s “ancient city”theory. identity and sense of belonging of the population. Each He views that social forms and the management system tribe had its own temple, temple play a role on the will change from the tribe to the national, and there will stability of settlement. Therefore tribes-temple-settlement be classes, strata and public power. Some tribal centers formation of highly conjoined effect. may have become political, economic and cultural center, or a capital[6]. -

Tibetan New Year and Great Prayer Festival Tour

www.sorigtour.com [email protected] TIBETAN NEW YEAR AND GREAT PRAYER FESTIVAL TOUR. January 31 - February 10 - 2020 and 11 days tour. Day (01) January 31/ 2020. Arrival in Xining: (2250m) Drive 45 m. Arrive in Xining train station or at airport we will be met by our Tibetan guide and driver who will travel with us throughout our time in Qinghai and Gansu province. Transfer to Hotel. Xining is a biggest city on Tibet plateau and it is the capital city of Northwest China’s Qinghai province. Visit the Tibetan Medical Museum and the biggest Thangka in Tibet. After dinner we will walk to see the New Year lights in Xining. (Overnight hotel in Xining.) L/D Day (02) February 1/ 2020 Xining—Repkong(Tongren) (2500m) Drive 3 hrs. Drive to Rebkong. Rebkong is home to large Tibetan Buddhist monasteries and Bon monastry. Also it is famous across Tibet for its artists. On the way visit Shachung monastery, which is located on a mountain top and has a great very view of the valley and the Yellow River. Afternoon visit Sanggeshong Yago (Wutun) monastery and today’s highlight is the grand ceremony of Thangka display on the slope of a hill to share the benefit of Buddhism with all the creature. Overnight hotel in Rebkong.B/L/D Day (03) February 2/ 2020. Rebkong (Tongren) (2500m) Drive 45 m. After breakfast, drive to Bongya, visit Bongya which is one of the Bon Monastery near Rebkong. Visit Bon ceremony. Afternoon we will vary program and view as many different ceremonies in the Village. -

5 Days Jiuzhaigou Huanglong Parks Plus Zoige Grassland and Langmusi Tour

[email protected] +86-28-85593923 5 days Jiuzhaigou Huanglong parks plus Zoige Grassland and Langmusi tour https://windhorsetour.com/jiuzhaigou-tour/jiuzhaigou-huanglong-zoige-tour Jiuzhaigou Huahu Langmusi Tangke Huanglong Besides the stunning natural views of Jiuzhaigou and Huanglong parks, you will also see the best grasslands of Tibetan plateau in Ruo'ergai, where are filled with yaks and sheep in summer, an excellent place to know the Tibetan nomad culture. Type Private Duration 5 days Theme Photography Trip code WS-404 Price From ¥ 4,000 per person Itinerary Day 01 : Fly to Jiuzhaigou / Drive to Jiuzhaigou Upon arrival at Jiuzhaigou airport. To be met and picked up by your local guide and driver, and drive to Jiuzhaigou ( 3 hours drive). After assist you on your hotel check-in, you can have a good rest at Jiuzhaigou to acclimatize the high attitude. Overnight at Jiuzhaigou. Day 02 : Sightseeing in Jiuzhaigou National Park(B) You will have one full day to spend at Jiuzhaigou National Park with crystal clear lakes, waterfalls, virgin forest, and Tibetan villages to explore. You can take the pollution free sightseeing buses to the top of the valley, then walk down to appreciate the nice scenery along the way.You will forget all the trobles, but just throw yourselves into the spectacular scenery in this treasured scenic site. In the evening, you will have the chance to see a local Tibetan-Qiang minority Culture show(Price not included). Overnight at Jiuzhaigou. Day 03 : Jiuzhaigou - 4.5 hours - Ruo'ergai - 2 hours - Langmusi (B) Today drive from Jiuzhaigou to Langmusi, about 320KM with 6 hours drive, enjoy the scenery along the way including the vast grasslands, nomadic herding sheep and yaks and snow capped mountains serving as backdrop. -

Discussion on the Integration and Optimization Plan of Natural Reserve-Take Gannan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture As an Example

E3S Web of Conferences 257, 03003 (2021) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202125703003 AESEE 2021 Discussion on the Integration and Optimization Plan of Natural Reserve-Take Gannan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture as an example Boqiang Zhai1,a*,Xitun Yuan2,b 1Xi'an University of Science and Technology, Xi’an, Shaanxi, China 2Xi'an University of Science and Technology, Xi’an, Shaanxi, China Abstract: The integration and optimization of nature reserves is an important part of the new round of land and space planning, and it is also an important part of building a system of nature reserves with national parks as the main body. This article takes Gannan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, which has many nature reserves and relatively complex conditions as an example, to summarize and study the technical and operational issues involved in the integration and optimization of 30 different types of nature reserves, natural parks and scenic spots in the region. We propose an integration and optimization plan that fits the region, focusing on the treatment of the overlapping and distributed residential land, basic farmland, and major construction projects of each protected area, and provide reasonable suggestions for the integration and optimization of the construction of natural reserves with Chinese characteristics. 1 Preface formed, and the management efficiency has been reduced, hindering the overall function; it cannot truly provide the According to the concept given by the International public with high-quality ecological products and support Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), a protected the economy The sustainable development of society is area is a clearly defined geographical area that is incompatible with the development requirements of the recognized by law or other effective means and aims to new era. -

Entropy-Based Research on Precipitation Variability in the Source Region of China’S Yellow River

water Article Entropy-Based Research on Precipitation Variability in the Source Region of China’s Yellow River Henan Gu 1,2,* , Zhongbo Yu 1,2,*, Guofang Li 2, Jian Luo 2, Qin Ju 1,2, Yan Huang 3 and Xiaolei Fu 4 1 State Key Laboratory of Hydrology-Water Resources and Hydraulic Engineering, Hohai University, Nanjing 210098, China; [email protected] 2 College of Hydrology and water resources, Hohai University, Nanjing 210098, China; [email protected] (G.L.); [email protected] (J.L.) 3 Fujian Provincial Investigation, Design & Research Institute of Water Conservancy & Hydropower, Fuzhou 350001, China; [email protected] 4 College of Civil Engineering, Fuzhou University, Fuzhou 350116, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (H.G.); [email protected] (Z.Y.); Tel.: +86-135-8520-9927 (H.G.); +025-8378-6721 (Z.Y.) Received: 15 August 2020; Accepted: 3 September 2020; Published: 5 September 2020 Abstract: The headwater regions in the Tibetan Plateau play an essential role in the hydrological cycle, however the variation characteristics in the long-term precipitation and throughout-the-year apportionment remain ambiguous. To investigate the spatio-temporal variability of precipitation in the source region of the Yellow River (SRYR), different time scale data during 1979–2015 were studied based on Shannon entropy theory. Long-term marginal disorder index (LMDI) was defined to evaluate the inter-annual hydrologic budget for annual (AP) and monthly precipitation (MP), and annual marginal disorder index (AMDI) to measure intra-annual moisture supply disorderliness for daily precipitation (DP). Results reveal that the AP over the SRYR exhibits remarkable variation, with an inclination rate of 2.7 mm/year, and a significant increasing trend. -

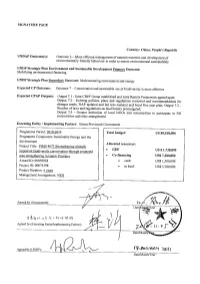

00059938 PRODOC.Pdf

United Nations Development Programme PROJECT DOCUMENT Government of China Gansu Provincial Government United Nations Development Programme PIMS 4072 - Strengthening Globally Important Biodiversity Conservation through Protected Area Strengthening in Gansu Province Brief Description Gansu Province covers a total land area of 454,000 km², harbouring 19% of vertebrate species recorded in China, and ranking 4th richest of all Chinese provinces in terms of mammal species richness and 7th in terms of bird species richness. As in most parts of China, biodiversity is under considerable threat in Gansu from habitat loss from logging from natural forests in the recent past; conversion of natural ecosystems (such as wetlands) to farmland, industries, and human settlements; overgrazing of grasslands and overharvesting of products from nature (such as medicinal plants). The government in Gansu has established an impressive PA network of 58 Nature Reserves covering 9,940,782 ha or 21.9% of the province to safeguard some of its most important sites for biodiversity conservation. Given the global and national importance of biodiversity in the PAs in Gansu Province, the long-term solution proposed by this project is an effectively managed nature reserves system in Gansu to conserve globally important biodiversity for the long-term. However, a number of barriers hamper effective management of the PAs. These barriers can be summarised into: (i) the management system for the Gansu nature reserves system suffers from fundamental weaknesses that undermine -

A Tale of 3 Provinces I Sichuan, Qinghai & Gansu Plus a Taste Of

A Tale of 3 Provinces I Sichuan, Qinghai & Gansu plus a taste of Xian 25June – 06July 2017 In this natural wonder getaway, where you can witness condors gliding across blue skies, explore nomad lifestyle, relax with a sip of milk tea and enjoy the stunning prairie sunset or sunrise. This is a place of magic, the home of yak, the world of wild flowers and the ocean of green grass. Here, the land is flat and the views are extensive; the pasture is lush and the cattle and sheep flocks ….. join us to this off the beaten track enchanting journey to capture these Tale of 3 Provinces , where the boundary beauties are endless . DAY 01 , 25 JUNE Sunday : KUALA LUMPUR – CHENGDU ( MOB ) Depart Kuala Lumpur for Chengdu on Air Asia flight D7 KUL CTU 1340 Upon Arrival Chengdu Airport, meet and greet by our local English Guide and drive to Dujiangyan to overnite.. Free and easy for paxs to walk along the old street of Dujiangyan Overnite in Dujiangyan Day 02, 26 JUNE Monday : Dujiangyan – EMUTANG PASTURE – HONGYUAN ( B/L/D) Wake up early to start our journey to Hongyuan. The spectacular Hongyuan (red plain) Grasslands was so named because the Red Army, over the course of a year, passed through here during the famous Long March in 1936. A plateau at over 3,000m (9843 feet) above sea level , stretching for over 8,400 sq.km., the Hongyuan Grasslands is said to be home to over 300,000 herded yak, 20m herded sheep and over 20,000 horses and many wild flowers in early summer. -

The Art of Neighbouring Making Relations Across China’S Borders the Art of Neighbouring Asian Borderlands

2 ASIAN BORDERLANDS Zhang (eds) Zhang The Art Neighbouring of The Edited by Martin Saxer and Juan Zhang The Art of Neighbouring Making Relations Across China’s Borders The Art of Neighbouring Asian Borderlands Asian Borderlands presents the latest research on borderlands in Asia as well as on the borderlands of Asia – the regions linking Asia with Africa, Europe and Oceania. Its approach is broad: it covers the entire range of the social sciences and humanities. The series explores the social, cultural, geographic, economic and historical dimensions of border-making by states, local communities and flows of goods, people and ideas. It considers territorial borderlands at various scales (national as well as supra- and sub-national) and in various forms (land borders, maritime borders), but also presents research on social borderlands resulting from border-making that may not be territorially fixed, for example linguistic or diasporic communities. Series Editors Tina Harris, University of Amsterdam Willem van Schendel, University of Amsterdam Editorial Board Members Franck Billé, University of Cambridge Duncan McDuie-Ra, University of New South Wales Eric Tagliacozzo, Cornell University Yuk Wah Chan, City University Hong Kong The Art of Neighbouring Making Relations Across China’s Borders Edited by Martin Saxer and Juan Zhang Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Trucks waiting in front of the Kyrgyz border at Torugart Pass. Photo: Martin Saxer, 2014 Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 94 6298 258 1 e-isbn 978 90 4853 262 9 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789462982581 nur 740 Creative Commons License CC BY (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0) Martin Saxer & Juan Zhang / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2017 All rights reserved. -

Culture Clash: Tourism in Tibet

Tibet Watch | April 2014 Culture Clash: Tourism in Tibet Tibet Watch Thematic Report October 2014 -1- Culture Clash: Tourism in Tibet Thematic report commissioned by Free Tibet Copyright © 2014 Tibet Watch All rights reserved. Tibet Watch works to promote the human rights of the Tibetan people through monitoring, research and advocacy. We are a UK registered charity (no. 1114404) with an office in London and a field office in Dharamsala, India. We believe in the power of bearing witness, the power of truth. www.tibetwatch.org Contents Introduction 1 Background 2 Tourism and freedom of movement 4 Getting into and around Tibet 4 Infrastructure development 6 Marketing Tibet 8 Culture clash and the ethics of tourism 11 Zangpiao – the Tibet Drifters 12 “She is Crying on the Hill” 14 Tibetan responses to tourism and travel on social media 21 Conclusion 24 Culture Clash: Tourism in Tibet | Tibet Watch 2014 Introduction This report was inspired by the discovery of She is Crying on the Hill, a blog post by a Chinese traveller named “December” which presents, and comments on, images of other Chinese tourists photographing Tibetans at the Taktsang Lhamo temple in a highly intrusive and aggressive manner. It is an evocative series of photographs and, as the author points out, many of the images are as disturbing as scenes of outright violence. They certainly raise questions about the social impact of tourism in Tibet and how it is being marketed by the Chinese government. Based primarily on online research, this report looks first at the development and scale of tourism in Tibet - how it has evolved from just a few thousand visitors each year to a lucrative industry which regularly sees Tibet flooded by a number of tourists exceeding its official population.