Charitable Practices of Muslim Americans in the Greater Kansas City Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

U.S. Muslim Charities and the War on Terror

U.S. Muslim Charities and the War on Terror A Decade in Review December 2011 Published: December 2011 by The Charity & Security Network (CSN) Front Cover Photo: Candice Bernd / ZCommunications (2009) Demonstrators outside a Dallas courtroom in October 2007during the Holy Land Foundation trial. Acknowledgements: Supported in part by a grant from the Open Society Foundation, Cordaid, the Nathan Cummings Foundation, Moriah Fund, Muslim Legal Fund of America, Proteus Fund and an Anonymous donor. We extend our thanks for your support. Written by Nathaniel J. Turner, Policy Associate, Charity & Security Network. Edited by Kay Guinane and Suraj K. Sazawal of the Charity & Security Network. Thanks to Mohamed Sabur of Muslim Advocates and Mazen Asbahi of the Muslim Public Affairs Council for reviewing the report, which benefitted from their suggestions. Any errors are solely those of CSN, not the reviewers. The Charity & Security Network is a network of humanitarian aid, peacebuilding and advocacy organizations seeking to eliminate unnecessary and counterproductive barriers to legitimate charitable work caused by current counterterrorism measures. Charity & Security Network 110 Maryland Avenue, Suite 108 Washington, D.C. 20002 Tel. (202) 481-6927 [email protected] www.charityandsecurity.org Table of Contents Executive Summary............................................................................................................................................ 3 Introduction......................................................................................................................................................... -

Bibliography of Works Consulted

98 Muslim Worldviews and the Bible: (Part III: Women, Purity, Worship and Ethics) One should bring honor to Christ, by honest means, x One should, by almost any means, promote and protect the even if one appears foolish to others or displeases honor of one’s family and of Islam. one’s family. One should seek guidance from God through the x One should seek guidance by learning the Islamic law and Bible, prayer, and the Holy Spirit. following it. Popular: One can seek divine guidance from saints and others who have a gift for this service. Believers should feel ashamed if they dishonor or displease | The Muslim generally feels ashamed when others reproach God. However, if they are following Christ, then they him or his family or a member of his family. Avoidance expect reproach and persecution from worldly people. of shame is perhaps the strongest factor affecting social behavior. The family should keep its womenfolk from shaming them by committing a sexual indiscretion; shame can be alleviated by strictly punishing the offending woman. One should practice hospitality even to strangers. ~ The practice of hospitality and generosity bring honor to the family; its lack brings dishonor. One should work and not be idle. Work with the X A man should not work if it is not necessary. Manual labour hands is honorable. is not honorable. IJFM Bibliography of Works Consulted Abdul-Khaliq, Abdur-Rahmaan Brown, Rick Cragg, Kenneth 1986 The General Prescripts of Belief 2000 The Son of God: Understanding 1988 The Pen and the Faith: Eight in the Qu’ran and Sunnah. -

ISLAMIC FOUNDATIONS of a FREE SOCIETY

ISLAMIC FOUNDATIONS of a FREE SOCIETY Edited by NOUH EL HARMOUZI & LINDA WHETSTONE Islamic Foundations of a Free Society ISLAMIC FOUNDATIONS OF A FREE SOCIETY EDITED BY NOUH EL HARMOUZI AND LINDA WHETSTONE with contributions from MUSTAFA ACAR • SOUAD ADNANE AZHAR ASLAM • HASAN YÜCEL BAŞDEMIR KATHYA BERRADA • MASZLEE MALIK • YOUCEF MAOUCHI HICHAM EL MOUSSAOUI • M. A. MUQTEDAR KHAN BICAN ŞAHIN • ATILLA YAYLA First published in Great Britain in 2016 by The Institute of Economic Affairs 2 Lord North Street Westminster London SW1P 3LB in association with London Publishing Partnership Ltd www.londonpublishingpartnership.co.uk The mission of the Institute of Economic Affairs is to improve understanding of the fundamental institutions of a free society by analysing and expounding the role of markets in solving economic and social problems. Copyright © The Institute of Economic Affairs 2016 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photo- copying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-0-255-36729-5 (interactive PDF) Many IEA publications are translated into languages other than English or are reprinted. Permission to translate or -

Supreme Court of the United States ______

No. 20-639 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States ________________________________ CALVARY CHAPEL DAYTON VALLEY, Petitioner, v. STEVE SISOLAK, GOVERNOR OF NEVADA, ET AL., Respondents. ________________________________ On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit ________________________________ BRIEF AMICI CURIAE ISLAM AND RELIGIOUS FREEDOM ACTION TEAM AND JEWISH COALITION FOR RELIGIOUS LIBERTY IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER ________________________________ HUNTON ANDREWS KURTH LLP ERICA N. PETERSON ELBERT LIN MICHAEL C. DINGMAN Counsel of Record 2200 Pennsylvania Ave. NW 951 East Byrd Street Washington, DC 20037 East Tower [email protected] Richmond, VA 23219 [email protected] [email protected] Phone: (202) 955-1500 Phone: (804) 788-8200 KATY BOATMAN 600 Travis, Suite 4200 Houston, Texas 77002 [email protected] Phone: (713) 220-4200 Counsel for Amici Curiae i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ....................................... ii INTRODUCTION AND INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE ................................................. 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .................................... 3 REASONS FOR GRANTING CERTIORARI ............ 4 I. This Court’s Review Is Necessary to Ensure Religious Freedom for Americans of All Faiths........................................................ 4 II. Nevada’s Directives Violate the Free Exercise Clause. ............................................... 16 A. Strict Scrutiny Analysis Applies to Nevada’s Directives. ............................... -

Holy Land Foundation for Relief and Development: Criminalizing Support for Non-Designated Charities

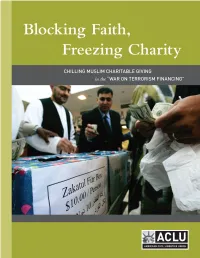

Blocking Faith, Freezing Charity CHILLING MUSLIM CHARITABLE GIVING in the “WAR ON TERRORISM FINANCING” Blocking Faith, Freezing Charity: Chilling Muslim Charitable Giving in the “War on Terrorism Financing” PUBLISHED: June 2009 FRONT COVER PHOTOGRAPH: Alex Wong/Getty Images Members of a Muslim congregation in Virginia give Zakat donations for the needy before they enter a mosque for a service to mark the conclusion of the holy month of Ramadan, the height of annual Muslim charitable giving. Zakat is one of the core “five pillars” of Islam and a religious obligation for all observant Muslims. BACK COVER PHOTOGRAPHS: LEFT: Brandon Dill/Memphis Commercial Appeal RIGHT: LIFE for Relief and Development THE AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION is the nation’s premier guardian of liberty, working daily in courts, legislatures and communities to defend and preserve the individual rights and freedoms guaranteed by the Constitution, the laws and treaties of the United States. OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS Susan N. Herman, President Anthony D. Romero, Executive Director Richard Zacks, Treasurer ACLU NATIONAL OFFICE 125 Broad Street, 18th Fl. New York, NY 10004-2400 (212) 549-2500 www.aclu.org Contents I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND INTRODUCTION ................................................................................ 7 a. Introduction .............................................................................................................................7 b. Executive Summary .................................................................................................................9 -

HOW ANERA CAME to BE ANERA Prehistory

HOW ANERA CAME TO BE ANERA Prehistory merican Near East Refugee Aid (ANERA) is Aone of the leading American non-government organizations (NGOs) active in the Occupied West Bank and Gaza and surrounding countries, supporting economic self-help projects and providing John Richardson, author of this publication, was emergency relief following hostilities between Israel ANERA’s first Executive Director and second President. and its Arab neighbors. ANERA’s seven regional He is a retired U.S. government official and author of offices (Jerusalem, Nablus, Ramallah, Hebron, The West Bank: A Portrait. Gaza, Amman, and Beirut), its robust operating budget of more than $76 million, and its record of The author wishes to thank the many participants in minimal management expenses and maximal direct ANERA’s creation who provided oral and documentary project support are all reasons for the organization’s support for this piece. Betty Sams, widow of Founder Jim Sams and an active participant in the events leadership role. leading up to ANERA’s creation, was gracious in Perhaps less well known is the unusual set of obtaining and providing access to Jim’s ANERA files. circumstances and factors that led to ANERA’s creation in the wake of the June 1967 Middle East war. An unusual set of circumstances and factors led ANERA grew out of a partnership that continues to to ANERA’s creation in the wake of the June 1967 this day between the Arab-American community and Middle East war. ANERA grew out of a partnership the American corporate-philanthropic community that continues to this day between the Arab- involved in the Middle East. -

In the Name of God, the Compassionate, the Merciful U.S

In the Name of God, the Compassionate, the Merciful U.S. MUSLIM RELIGIOUS COUNCIL ISSUES FATWA AGAINST TERRORISM The Fiqh Council of North America wishes to reaffirm Islam's absolute condemnation of terrorism and religious extremism. Islam strictly condemns religious extremism and the use of violence against innocent lives. There is no justification in Islam for extremism or terrorism. Targeting civilians’ life and property through suicide bombings or any other method of attack is haram – or forbidden - and those who commit these barbaric acts are criminals, not “martyrs.” The Qur’an, Islam’s revealed text, states: "Whoever kills a person [unjustly]…it is as though he has killed all mankind. And whoever saves a life, it is as though he had saved all mankind." (Qur’an, 5:32) Prophet Muhammad said there is no excuse for committing unjust acts: "Do not be people without minds of your own, saying that if others treat you well you will treat them well, and that if they do wrong you will do wrong to them. Instead, accustom yourselves to do good if people do good and not to do wrong (even) if they do evil." (Al-Tirmidhi) God mandates moderation in faith and in all aspects of life when He states in the Qur’an: “We made you to be a community of the middle way, so that (with the example of your lives) you might bear witness to the truth before all mankind.” (Qur’an, 2:143) In another verse, God explains our duties as human beings when he says: “Let there arise from among you a band of people who invite to righteousness, and enjoin good and forbid evil.” (Qur’an, 3:104) Islam teaches us to act in a caring manner to all of God's creation. -

The Wages of Extremism: Radical Islam’S Threat to the West and the Muslim World

SECURITY & FOREIGN AFFAIRS The Wages of Extremism: Radical Islam’s Threat to the West and the Muslim World By Alexander R. Alexiev March 2011 The Wages of Extremism: Radical Islam's Threat to the West and the Muslim World Alexander R. Alexiev Visiting Fellow, Hudson Institute March 2011 © 2011 Hudson Institute Hudson Institute is a nonpartisan, independent policy research organization. Founded in 1961, Hudson is celebrating a half century of forging ideas that promote security, prosperity, and freedom. www.hudson.org Table of Contents Chapter I: Introduction................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter II: The Nature of the Threat......................................................................................... 8 Chapter III: The Ideology of Radical Islam............................................................................. 12 Sharia Law and Radical Islam............................................................................................... 12 Sharia Law – Profile of a Radical Doctrine........................................................................... 13 Key Doctrinal Concepts: External and Internal Enemy, Islamic Vanguard.......................... 20 Chapter IV: The Limited Scope of Sharia in Past Muslim Empires ..................................... 27 Sharia in Muslim History ...................................................................................................... 27 The Umayyad Empire........................................................................................................... -

Terrorism Sanctions Regulations (Title 31 Part 595 of the U.S

Executive Order 13224 blocking Terrorist Property and a summary of the Terrorism Sanctions Regulations (Title 31 Part 595 of the U.S. Code of Federal Regulations), Terrorism List Governments Sanctions Regulations (Title 31 Part 596 of the U.S. Code of Federal Regulations), and Foreign Terrorist Organizations Sanctions Regulations (Title 31 Part 597 of the U.S. Code of Federal Regulations) EXECUTIVE ORDER 13224 - BLOCKING PROPERTY AND PROHIBITING TRANSACTIONS WITH PERSONS WHO COMMIT, THREATEN TO COMMIT, OR SUPPORT TERRORISM By the authority vested in me as President by the Constitution and the laws of the United States of America, including the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (50 U.S.C. 1701 et seq.)(IEEPA), the National Emergencies Act (50 U.S.C. 1601 et seq.), section 5 of the United Nations Participation Act of 1945, as amended (22 U.S.C. 287c) (UNPA), and section 301 of title 3, United States Code, and in view of United Nations Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 1214 of December 8, 1998, UNSCR 1267 of October 15, 1999, UNSCR 1333 of December 19, 2000, and the multilateral sanctions contained therein, and UNSCR 1363 of July 30, 2001, establishing a mechanism to monitor the implementation of UNSCR 1333, I, GEORGE W. BUSH, President of the United States of America, find that grave acts of terrorism and threats of terrorism committed by foreign terrorists, including the terrorist attacks in New York, Pennsylvania, and the Pentagon committed on September 11, 2001, acts recognized and condemned in UNSCR 1368 of September 12, 2001, and UNSCR 1269 of October 19, 1999, and the continuing and immediate threat of further attacks on United States nationals or the United States constitute an unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security, foreign policy, and economy of the United States, and in furtherance of my proclamation of September 14, 2001, Declaration of National Emergency by Reason of Certain Terrorist Attacks, hereby declare a national emergency to deal with that threat. -

2020-21 Nevada Educational Choice Scholarship Program Report

2020-21 Nevada Educational Choice Scholarship Program Report This report to the Governor, the Director of the Legislative Council Bureau, and the State Board of Education fulfills the regulatory requirement per NAC 388D.070 that the Nevada Department of Education (NDE or Department) submit a report by March 30th summarizing the information reported to the NDE by the registered scholarship granting organizations. 2020-21 Nevada Educational Choice Scholarship Program Report Program Description The Nevada Educational Choice Scholarship Program (often referred to as Opportunity Scholarships), was enacted by law effective July 1, 2015. The scholarship program allows a student whose family has a household income not more than 300 percent of the federal poverty level to apply for a scholarship from an approved scholarship granting organization. The scholarship provides support for the student to attend a registered private school, pay the fees for distance education programs and/or dual credit programs in Nevada public schools, and cover the transportation costs if the school does not offer transportation. It is important to note that this report was completed during the course of NDE’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, the capacity for the completion of the report includes one Education Programs Professional who is assigned to support this work at approximately 25% of their time. Lastly, regarding the assessment data, the information received by NDE represents non-standardized data sources. 2020 Federal Poverty Guidelines Household -

SMART Jamaat App IFN Reopening Salah Registration Requirements

slamic Foundation North Reopening July 1st, 2020 SMART Jamaat App IFN Reopening Salah Registration Requirements Every attendee must register Perform wadu before coming to masjid Please come 20 minutes before salah time Wear a face mask at all times while on IFN Premises Please park your vehicle leaving one parking spot Bring your own prayer rug or Musallah Every attendee will be scanned for temperature at the If you feel sick, please stay at home entrance Maintain social distancing of 6 feet or more at all times Pray on designated marked prayer spots only Pray Sunnah before or after the Salah at home No socializing in the Masjid Lobby, Musallah, stairways or parking lot No handshakes, hugs, no kiss on cheeks Kids 12 and under are not allowed at this time Please return to your vehicle to exit the premises upon completion of the Fard Salah SMART Jamaat Application • The purpose of SMART Jamaat App is to allow the IFN Masjid to have the people reserve, cancel, check-in and manage their jamaat spot • This will allow Masjid to control the number of people for each Jamaat ensuring the social distancing protocols and enhance safety • The Check-In process will in future be automatic allowing Masjid to free up resources and at the same time maintain contact tracing requirements that will need to be enforced SMART Jamaat – Download • For iPhone users download the Smart Jamaat Application from the Apple AppStore • For Android users download the Smart Jamaat Application from the Play Store SMART Jamaat – Select a Masjid • This will be the Home page for making Reservations • The list is searchable list to find a masjid. -

Muslim Networks and Movements in Western Europe

Muslim Networks and Movements in Western Europe SEPTEMBER 2010 Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life Muslim Networks and Movements in Western Europe FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Luis Lugo, Director Alan Cooperman, Associate Director, Research Erin O’Connell, Associate Director, Communications Sandra Stencel, Associate Director, Editorial (202) 419-4550 www.pewforum.org 2 PEw FORUM ON RELIgION & PUbLIC LIFE A bout the Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life This report was produced by the Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion & Public Life. The Pew Forum delivers timely, impartial information on issues at the intersection of religion and public affairs. The Pew Forum is a nonpartisan, nonadvocacy organization and does not take positions on policy debates. Based in Washington, D.C., the Pew Forum is a project of the Pew Research Center, which is funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts. The report is a collaborative effort based on the input and analysis of the following individuals: Primary Researcher Peter Mandaville, Director, Center for Global Studies, and Professor of Government and Islamic Studies, George Mason University; Visiting Fellow 2009-10, Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life Pew Forum Pew Research Center Luis Lugo, Director Andrew Kohut, President Paul Taylor, Executive Vice President Research Elizabeth Mueller gross, Vice President Alan Cooperman, Associate Director, Research Scott Keeter, Director of Survey Research David Masci, Senior Researcher Richard wike, Associate Director, Elizabeth Podrebarac, Research Assistant Pew Global