DID SHE CHANGE: Exploring Cello in Documentary Songwriting and Expanding the Role of a Classical Cellist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Booklet

SIGCD656_16ppBklt**.qxp_BookletSpread.qxt 19/11/2020 17:06 Page 1 CTP Template: CD_DPS1 COLOURS Compact Disc Booklet: Double Page Spread CYAN MAGENTA Customer YELLOW Catalogue No. BLACK Job Title Page Nos. 16 1 291.0mm x 169.5mm SIGCD656_16ppBklt**.qxp_BookletSpread.qxt 19/11/2020 17:06 Page 2 CTP Template: CD_DPS1 COLOURS Compact Disc Booklet: Double Page Spread CYAN MAGENTA Customer YELLOW Catalogue No. BLACK Job Title Page Nos. rEDISCOvErEd British Clarinet Concertos Dolmetsch • Maconchy • Spain-Dunk • Wishart 1. Cantilena (Poem) for Clarinet and Orchestra, Op. 51 * Susan Spain-Dunk (1880-1962) ............[11.32] Concertino for Clarinet and String Orchestra Elizabeth Maconchy (1907-1994) 2. I. Allegro .....................................................................................................................................................................................................................[5.01] 3. II. Lento .......................................................................................................................................................................................................................[6.33] 4. III. Allegro ................................................................................................................................................................................................................. [5.32] Concerto for Clarinet, Harp and Orchestra * Rudolph Dolmetsch (1906-1942) 5. I. Allegro moderato ......................................................................................................................................................................................[10.34] -

Delius Monument Dedicatedat the 23Rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn

The Delius SocieQ JOUrnAtT7 Summer/Autumn1992, Number 109 The Delius Sociefy Full Membershipand Institutionsf 15per year USA and CanadaUS$31 per year Africa,Australasia and Far East€18 President Eric FenbyOBE, Hon D Mus.Hon D Litt. Hon RAM. FRCM,Hon FTCL VicePresidents FelixAprahamian Hon RCO Roland Gibson MSc, PhD (FounderMember) MeredithDavies CBE, MA. B Mus. FRCM, Hon RAM Norman Del Mar CBE. Hon D Mus VernonHandley MA, FRCM, D Univ (Surrey) Sir CharlesMackerras CBE Chairman R B Meadows 5 WestbourneHouse. Mount ParkRoad. Harrow. Middlesex HAI 3JT Ti,easurer [to whom membershipenquiries should be directed] DerekCox Mercers,6 Mount Pleasant,Blockley, Glos. GL56 9BU Tel:(0386) 700175 Secretary@cting) JonathanMaddox 6 Town Farm,Wheathampstead, Herts AL4 8QL Tel: (058-283)3668 Editor StephenLloyd 85aFarley Hill. Luton. BedfordshireLul 5EG Iel: Luton (0582)20075 CONTENTS 'The others are just harpers . .': an afternoon with Sidonie Goossens by StephenLloyd.... Frederick Delius: Air and Dance.An historical note by Robert Threlfall.. BeatriceHarrison and Delius'sCello Music by Julian Lloyd Webber.... l0 The Delius Monument dedicatedat the 23rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn........ t4 Fennimoreancl Gerda:the New York premidre............ l1 -Opera A Village Romeo anrl Juliet: BBC2 Season' by Henry Gi1es......... .............18 Record Reviews Paris eIc.(BSO. Hickox) ......................2l Sea Drift etc. (WNOO. Mackerras),.......... ...........2l Violin Concerto etc.(Little. WNOOO. Mackerras)................................22 Violin Concerto etc.(Pougnet. RPO. Beecham) ................23 Hassan,Sea Drift etc. (RPO. Beecham) . .-................25 THE HARRISON SISTERS Works by Delius and others..............26 A Mu.s:;r1/'Li.fe at the Brighton Festival ..............27 South-WestBranch Meetinss.. ........30 MicllanclsBranch Dinner..... ............3l Obittrary:Sir Charles Groves .........32 News Round-Up ...............33 Correspondence....... -

Navigating, Coping & Cashing In

The RECORDING Navigating, Coping & Cashing In Maze November 2013 Introduction Trying to get a handle on where the recording business is headed is a little like trying to nail Jell-O to the wall. No matter what side of the business you may be on— producing, selling, distributing, even buying recordings— there is no longer a “standard operating procedure.” Hence the title of this Special Report, designed as a guide to the abundance of recording and distribution options that seem to be cropping up almost daily thanks to technology’s relentless march forward. And as each new delivery CONTENTS option takes hold—CD, download, streaming, app, flash drive, you name it—it exponentionally accelerates the next. 2 Introduction At the other end of the spectrum sits the artist, overwhelmed with choices: 4 The Distribution Maze: anybody can (and does) make a recording these days, but if an artist is not signed Bring a Compass: Part I with a record label, or doesn’t have the resources to make a vanity recording, is there still a way? As Phil Sommerich points out in his excellent overview of “The 8 The Distribution Maze: Distribution Maze,” Part I and Part II, yes, there is a way, or rather, ways. But which Bring a Compass: Part II one is the right one? Sommerich lets us in on a few of the major players, explains 11 Five Minutes, Five Questions how they each work, and the advantages and disadvantages of each. with Three Top Label Execs In “The Musical America Recording Surveys,” we confirmed that our readers are both consumers and makers of recordings. -

Central Reference CD List

Central Reference CD List January 2017 AUTHOR TITLE McDermott, Lydia Afrikaans Mandela, Nelson, 1918-2013 Nelson Mandela’s favorite African folktales Warnasch, Christopher Easy English [basic English for speakers of all languages] Easy English vocabulary Raifsnider, Barbara Fluent English Williams, Steve Basic German Goulding, Sylvia 15-minute German learn German in just 15 minutes a day Martin, Sigrid-B German [beginner’s CD language course] Berlitz Dutch in 60 minutes Dutch [beginner’s CD language course] Berlitz Swedish in 60 minutes Berlitz Danish in 60 minutes Berlitz Norwegian in 60 minutes Berlitz Norwegian phrase book & CD McNab, Rosi Basic French Lemoine, Caroline 15-minute French learn French in just 15 minutes a day Campbell, Harry Speak French Di Stefano, Anna Basic Italian Logi, Francesca 15-minute Italian learn Italian in just 15 minutes a day Cisneros, Isabel Latin-American Spanish [beginner’s CD language course] Berlitz Latin American Spanish in 60 minutes Martin, Rosa Maria Basic Spanish Cisneros, Isabel Spanish [beginner’s CD language course] Spanish for travelers Spanish for travelers Campbell, Harry Speak Spanish Allen, Maria Fernanda S. Portuguese [beginner’s CD language course] Berlitz Portuguese in 60 minutes Sharpley, G.D.A. Beginner’s Latin Economides, Athena Collins easy learning Greek Garoufalia, Hara Greek conversation Berlitz Greek in 60 minutes Berlitz Hindi in 60 minutes Berlitz Hindi travel pack Bhatt, Sunil Kumar Hindi : a complete course for beginners Pendar, Nick Farsi : a complete course for beginners -

BRITISH and COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS from the NINETEENTH CENTURY to the PRESENT Sir Edward Elgar

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Sir Edward Elgar (1857-1934) Born in Broadheath, Worcestershire, Elgar was the son of a music shop owner and received only private musical instruction. Despite this he is arguably England’s greatest composer some of whose orchestral music has traveled around the world more than any of his compatriots. In addition to the Conceros, his 3 Symphonies and Enigma Variations are his other orchestral masterpieces. His many other works for orchestra, including the Pomp and Circumstance Marches, Falstaff and Cockaigne Overture have been recorded numerous times. He was appointed Master of the King’s Musick in 1924. Piano Concerto (arranged by Robert Walker from sketches, drafts and recordings) (1913/2004) David Owen Norris (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/BBC Concert Orchestra ( + Four Songs {orch. Haydn Wood}, Adieu, So Many True Princesses, Spanish Serenade, The Immortal Legions and Collins: Elegy in Memory of Edward Elgar) DUTTON EPOCH CDLX 7148 (2005) Violin Concerto in B minor, Op. 61 (1909-10) Salvatore Accardo (violin)/Richard Hickox/London Symphony Orchestra ( + Walton: Violin Concerto) BRILLIANT CLASSICS 9173 (2010) (original CD release: COLLINS CLASSICS COL 1338-2) (1992) Hugh Bean (violin)/Sir Charles Groves/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Violin Sonata, Piano Quintet, String Quartet, Concert Allegro and Serenade) CLASSICS FOR PLEASURE CDCFP 585908-2 (2 CDs) (2004) (original LP release: HMV ASD2883) (1973) -

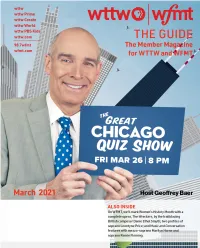

Geoffrey Baer, Who Each Friday Night Will Welcome Local Contestants Whose Knowledge of Trivia About Our City Will Be Put to the Test

From the President & CEO The Guide The Member Magazine Dear Member, for WTTW and WFMT This month, WTTW is excited to premiere a new series for Chicago trivia buffs and Renée Crown Public Media Center curious explorers alike. On March 26, join us for The Great Chicago Quiz Show hosted by 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60625 WTTW’s Geoffrey Baer, who each Friday night will welcome local contestants whose knowledge of trivia about our city will be put to the test. And on premiere night and after, visit Main Switchboard (773) 583-5000 wttw.com/quiz where you can play along at home. Turn to Member and Viewer Services page 4 for a behind-the-scenes interview with Geoffrey and (773) 509-1111 x 6 producer Eddie Griffin. We’ll also mark Women’s History Month with American Websites wttw.com Masters profiles of novelist Flannery O’Connor and wfmt.com choreographer Twyla Tharp; a POV documentary, And She Could Be Next, that explores a defiant movement of women of Publisher color transforming politics; and Not Done: Women Remaking Anne Gleason America, tracing the last five years of women’s fight for Art Director Tom Peth equality. On wttw.com, other Women’s History Month subjects include Emily Taft Douglas, WTTW Contributors a pioneering female Illinois politician, actress, and wife of Senator Paul Douglas who served Julia Maish in the U.S. House of Representatives; the past and present of Chicago’s Women’s Park and Lisa Tipton WFMT Contributors Gardens, designed by a team of female architects and featuring a statue by Louise Bourgeois; Andrea Lamoreaux and restaurateur Niquenya Collins and her newly launched Afro-Caribbean restaurant and catering business, Cocoa Chili. -

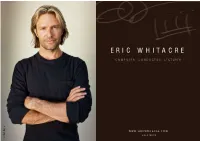

Eric Whitacre Press

E R I C W H I T A C R E E R I C W H I T A C R E C O M P O S E R , C O N D U C T O R , L E C T U R E R e c y o R W W W . E R I C W H I T A C R E . C O M c r a M J U L Y 2 0 1 2 © Music Productions Ltd. - +44 (0) 1753 783 739 - Claire Long, Manager - [email protected] E R I C W H I T A C R E B I O G R A P H Y ´:KLWDFUHLVWKDWUDUHWKLQJDPRGHUQFRPSRVHUZKRLV Eric Whitacre is one of the most popular and performed His latest initiative, Soaring Leap, is a series of workshops and ERWK SRSXODU DQG RULJLQDOµ 7KH 'DLO\ 7HOHJUDSK composers of our time, a distinguished conductor, broadcaster festivals. Guest speakers, composers and artists, make regular and public speaker. His first album as both composer and appearances at Soaring Leap events around the world. conductor on Decca/Universal, Light & Gold, won a Grammy® in 2012, reaped unanimous five star reviews and became the An exceptional orator, he was honoured to address the U.N. no. 1 classical album in the US and UK charts within a week of Leaders programme and give a TEDTalk in March 2011 in which release. His second album, Water Night, was released on Decca he earned the first full standing ovation of the conference. He in April 2012 and debuted at no. -

Elgar Cello Concerto Op. 85 • "Enigma" Variations Mp3, Flac, Wma

Elgar Cello Concerto Op. 85 • "Enigma" Variations mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Cello Concerto Op. 85 • "Enigma" Variations Country: Netherlands Released: 1985 MP3 version RAR size: 1335 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1469 mb WMA version RAR size: 1823 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 648 Other Formats: VOX MOD AIFF MP3 MPC XM DTS Tracklist Cello Concerto In E Minor, Op. 85 A1 Adagio - Moderato A2 Lento - Allegro Molto A3 Adagio A4 Allegro Variations On An Original Theme, Op. 36 "Enigma" B.1 Theme (Andante) B.2 1. C.A.E. (L'Istesso Tempo) B.3 2. H.D.S.-P. (Allegro) B.4 3. R.B.T. (Allegretto) B.5 4. W.M.B. (Allegro Di Molto) B.6 5. R.P.A. (Moderato) B.7 6. Ysobel (Andantino) B.8 7. Troyte (Presto) B.9 8. W. N. (Allegretto) B.10 9. Nimrod (Adagio) B.11 10. Intermezzo: Dorabella (Allegretto) B.12 11. G.R.S. (Allegro Di Molto) B.13 12. B.G.N. (Andante) B.14 13. Romanza: *** (Moderato) B.15 14. Finale: E.D.U. (Allegro - Presto) Credits Cello – Julian Lloyd Webber Composed By – Elgar* Conductor – Yehudi Menuhin Orchestra – Royal Philharmonic Orchestra* Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Elgar*, Julian Lloyd Webber, Elgar*, Julian Lloyd Royal Philharmonic Webber, Royal Orchestra*, Sir Yehudi 416 354-2 Philharmonic Philips 416 354-2 Germany 1985 Menuhin* - Cello Concerto Op. Orchestra*, Sir Yehudi 85 • "Enigma" Variations (CD, Menuhin* Album) Comments about Cello Concerto Op. 85 • "Enigma" Variations - Elgar Lbe If I could take just one piece of music with me on a desert island, it would be the Elgar cello concerto.I owe over ten versions of this concerto, on LP, CD and SACD, from the early 1928 recording with Beatrice Harrison and the LSO conducted by the composer himself, to the more recent version with Alisa Weilerstein. -

John Ireland in Chelsea'; a Festival to Commemorate the 50Th Anniversary of the Death of John Ireland

A Welcome from the Artistic Director: David Wordsworth Welcome to 'John Ireland in Chelsea'; a Festival to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the death of John Ireland. When Bruce Philips, (Director of the John Ireland Trust), and I first discussed this anniversary year I remember him telling me that various Ireland-related events were scheduled to take place throughout the year. This started me thinking how interesting it would be to hear more of this remarkable but still neglected music, programmed together and in venues particularly close to Ireland's heart, alongside woks of his pupils and teacher. Although sung and played in churches the world over, the music of Charles Villiers Stanford is still little-known and sadly dismissed, by those who haven't really heard it, as 'watered down Brahms', so it has been wonderful to be able to programme some of his solo/part-songs, as well as what is, by any standards, a major chamber work; the 2nd Piano Quartet, played by the London Soloists Ensemble, who are making their London debut as an ensemble. Ireland's reputation as a teacher has had something of a bad press in recent years, thanks in no small way to the publication of Benjamin Britten's 'tell all' diaries and letters. These documents serve rather to demonstrate that the young Britten had a pretty poor opinion of anyone apart from himself, although there cannot be any doubt that his teacher was a little jealous of his young contemporary’s enormous talent. Relations between Ireland and Britten became warmer in later years, but with 2013 on the horizon it was never my intention to feature too much of Britten's music, but it is good to be able hear a piece written whilst he was studying with Ireland; the 'Three Divertienti', and a rare performance of his Russian Funeral Music. -

New on Naxos | October 2013

NEW ON The World’s Leading ClassicalNAX MusicOS Label OCTOBER 2013 © Mark McNulty This Month’s Other Highlights © 2013 Naxos Rights US, Inc. • Contact Us: [email protected] www.naxos.com • www.classicsonline.com • www.naxosmusiclibrary.com • blog.naxos.com NEW ON NAXOS | october 2013 © Mark McNulty Vasily Petrenko Dmitry SHOSTAKOVICH (1906–1975) Symphony No. 4 in C minor, Op. 43 Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra • Vasily Petrenko Completed in 1936 but withdrawn during rehearsal and not performed until 1961, the searing Fourth Symphony finds Shostakovich stretching his musical idiom to the limit in the search for a personal means of expression at a time of undoubted personal and professional crisis. The opening movement, a complex and unpredictable take on sonata form that teems with a dazzling profusion of varied motifs, is followed by a short, eerie central movement. The finale opens with a funeral march leading to a climax of seismic physical force that gives way to a bleak and harrowing minor key coda. The Symphony has since become one of the most highly regarded of the composer’s large-scale works. Vasily Petrenko was appointed Principal Conductor of the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra in 2006 and in 2009 became Chief Conductor. He is also Chief Conductor of the Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra, Principal Guest Conductor of the Mikhailovsky Theatre of his native St Petersburg, 8.573188 Playing Time: 64:59 and Principal Conductor of the National Youth Orchestra of Great Britain. 7 47313 31887 2 Companion Titles 8.572082 8.572167 8.572392 8.572461 © Mark McNulty 8.572396 8.572658 8.572708 8.573057 Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra 2 NEW ON NAXOS | OCTOBER 2013 © Grant Leighton Marin Alsop Sergey PROKOFIEV (1891–1953) Symphony No. -

Programme Information

Programme information Saturday 6th April to Friday 12th April 2019 WEEK 15 Above: Alan Titchmarsh and Rob Cowan ANDRE PREVIN: A LIFE IN MUSIC (continueD) Saturday 6th April 7am to 10am: Alan TitcHmarsH 7pm to 9pm: Cowan’s Classics with Rob Cowan On what would have been André Previn’s 90th birthday, Alan Titchmarsh and Rob Cowan complete Classic FM’s week-long tribute to the great conductor, pianist and composer. From Rob Cowan: “Celebrating what would have been André Previn’s 90th on Cowan’s Classics brings back precious memories of a breakfast interview in Vienna back in 1997, talking to the great man about Ravel, Richard Strauss, Vaughan Williams, Mozart and film music. I remember his suave manner, caustic wit and obvious enthusiasm for the music he loved most. I’ve a terrific selection planned, ranging from Vaughan Williams evoking Westminster at night, to something sleek and sweet by Previn himself, Satie’s restful Gymnopedie No. 1 and Rachmaninov’s most famous piano concerto with Vladimir Ashkenazy as soloist. Here’s hoping that on Classic FM, I play all the right pieces in the right order...” Classic FM is available across the UK on 100-102 FM, DAB Digital radio anD TV, the Classic FM app, at ClassicFM.com and on the Global Player. 1 WEEK 15 SATURDAY 6TH APRIL 7am to 10am: ALAN TITCHMARSH Join Alan for his Great British Discovery and Gardening Tip after 8am, followed by a very special Classic FM Hall of Fame Hour at 9am. André Previn died in February at the age of 89; today would have been his 90th birthday, so, ahead of a special programme with Rob Cowan tonight, Alan dedicates the Classic FM Hall of Fame Hour to Previn’s finest recordings as both conductor and pianist. -

AM Order of Worship

` July 4, 2021 We Humbly Approach God God Speaks to Us in His Word Led by the Holy Spirit, LaGrave’s members seek The Call to Confession: Ephesians 2:11-18 The Children’s Message to worship and serve God in all of life, transforming His world and being transformed to reflect the The Prayer of Confession: The Scripture: Acts 10:23b-48 character of Christ. Lord God, forgive, restore, and strengthen us out of the Welcome to worship at LaGrave. Because our worship proceeds glorious riches of your grace. Make our souls wide and The Sermon: “PENTECOST, PART II” without announcements, please carefully follow the order of long and high and deep so that you can dwell in our worship printed below, noting that we use two different red hearts and church by faith. Root us in the love of Jesus We Respond with Praise hymnals. The Worship & Rejoice hymnal will be indicated by bold, Christ, according to your power that is at work in us, so italic type. An asterisk (*) denotes standing for those who are able. that the church of all times and places and tribes and The Prayer after the Sermon We are glad that you are here. Let us worship God together. people will glorify you now and forever. Amen. *The Closing Hymn: Lift Up Your Hearts 268 MORNING WORSHIP 10:00 AM “In Christ There Is No East or West” The Assurance of Forgiveness: Ephesians 2:19-22 Please prepare your heart and mind for worship with a time of prayer and meditation. *The Hymn of Commitment: Lift Up Your Hearts 269 God Sends Us into His World “All Are Welcome” God Calls Us to Worship *The Benediction The Anthem: The Prelude: *The People’s Response: Amen.