Blonde Journalism 1 Introduction When Two Blonde Bombshells from Hollywood Found Themselves in Trouble, They Also Found Themselv

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seven Footprints to Satan Saturday 24 March 2018 Performing Live: Jane Gardner and Roddy Long

Seven Footprints to Satan Saturday 24 March 2018 Performing live: Jane Gardner and Roddy Long This is a real rarity: the middle of three spooky house films made by Danish director Benjamin Christensen, who's best known for the satanic documentary Haxan, AKA Witchcraft Through the Ages. The other films are lost, though the music and sound effects discs that once accompanied The Haunted House can be heard on YouTube: lots of whistling wind and hooting owls. You might want to imagine those sounds as you experience Seven Footprints, whose original score and FX are lost: but we'll endeavour to make up for that with our own live accompaniment. Christensen came over at the same time as Garbo, and for a while looked to be making a go of it in Hollywood, directing successful films at MGM and Warner Bros. His very weird sensibility seems surreal now, but apparently fitted into the commercial cinema of the day. Seven Footprints is based on a perfectly serious mystery novel, but the director rewrote it from scratch and turned it into a bizarre and hilarious parody, a parade of sensational events with scarcely any narrative connection. We're just trapped in a spooky house with a nice couple being terrorized by a criminal cult, led by... Satan himself! The relentless succession of thugs, dwarfs, fiendish orientals, sinister cripples, phony gorillas, ludicrous grotesques and exotic women, all entering and exiting through secret panels, usually carrying pistols (except the gorilla) and uttering baffling warnings, plays like a Fu Manchu movie viewed through an opium haze. -

2006 Thelma Todd Celebration

Slapstick Magazine Presents 2006 Thelma Todd Celebration July 27 - July 30 Manchester, New Hampshire Join us as we celebrate the centenary of Thelma Todd, the Merrimack Valley’s queen of comedy Film Program As we draw nearer to the event, additional titles are likely to become available. Accordingly, the roster below may see some minor changes. There is ample free parking at UNH. THURSDAY, July 27th Fay Tincher - Ethel’s Roof Party UNH Hall, Commercial Street, Manchester Mabel Normand - A Muddy Romance (All titles in 16mm except where noted) Alice Howell - One Wet Night Wanda Wiley - Flying Wheels AM Edna Marian - Uncle Tom’s Gal 9:00 Morning Cartoon Hour 1 Gale Henry - Soup to Nuts Rare silent/sound cartoons Mary Ann Jackson - Smith’s Candy Shop 10:00 Charley Chase Silents (fragment) What Women Did for Me Anita Garvin/Marion Byron - A Pair of Tights Hello Baby ZaSu Pitts/Thelma Todd - One Track Minds Mama Behave (also features Spanky McFarland) A Ten Minute Egg 11:00 Larry Semon Shorts 9:30 Shaskeen Irish Pub, 909 Elm Street (directly across Titles TBA till from City Hall) 12:00 LUNCH (1 hour) close Silent and sound shorts featuring: Laurel and Hardy PM W.C. Fields 1:00 ZaSu Pitts - Thelma Todd Shorts Buster Keaton The Pajama Party The Three Stooges Seal Skins Asleep in the Feet 2:00 Snub Pollard and Jimmy Parrott FRIDAY, July 28th Sold at Auction (Pollard) UNH Hall, Commercial Street, Manchester Fully Insured (Pollard) (All titles in 16mm except where noted) Pardon Me (Pollard) AM Between Meals (Parrott) 9:00 Morning Cartoon Hour 2 -

Child-Theft Across Visual Media

The Child-theft Motif in the Silent Film Era and Afterwards 7 The Child-theft Motif in the Silent Film Era and Afterwards — ※ — During the silent film era (1894–1927), the story of children who are stolen by ‘gypsies’ and then rescued/restored to their families resurfaces as one of the popular stock plots. I refrain here from analysing individ- ual films and offer, instead, two points for further consideration: firstly, a listing of works that stage the motif under discussion, and secondly, an expanded annotated filmography. The Films 1. Rescued by Rover (1905, UK) 2. Two Little Waifs (1905, UK) 3. Ein Jugendabenteuer (1905, UK) 4. Rescued by Carlo (1906, USA) 5. The Horse That Ate the Baby (1906, UK) 6. The Gypsies; or, The Abduction (1907, France/UK) 7. The Adventures of Dollie (1908, USA) 8. Le Médaillon (1908, France) 9. A Gallant Scout (1909, UK) 10. Ein treuer Beschützer (1909, France) 11. Scouts to the Rescue (1909, UK) 12. Il trovatore (1910, Italy/France) 13. Billy’s Bulldog (1910, UK) 14. The Little Blue Cap (1910, UK) 15. The Squire’s Romance (1910, UK) 16. L’Enfant volé (1910, France) 129 The Child-theft Motif in the Silent Film Era and Afterwards 17. L’Evasion d’un truand (1910, France) 18. L’Enfant des matelots (1910, France) 19. Le Serment d’un Prince (1910, France) 20. L’Oiseau s’envole (1911, France) 21. Children of the Forest (1912, UK) 22. Ildfluen(1913, Denmark) 23. La gitanilla (1914, Spain) 24. La Rançon de Rigadin (1914, France) 25. Zigeuneren Raphael (1914, Denmark) 26. -

Leroy Shield's Music for the Wurlitzer

Carousel Organ, Issue No. 46—January, 2011 Leroy Shield’s Music for the Wurlitzer 165 “Crossovers”—Sharing our Hobby Tracy M. Tolzmann t is obvious to any collector of automatic music— Just such an occasion arose recently with the release especially street, band and fair organs—that much of of Wurlitzer 165 roll number 6846. This newly commis- Ithe enjoyment we get out of our hobby is the sharing sioned roll is made up of 14 selections written by the lit- of our collections with the non-collector public. It is also tle-known composer Leroy Shield. I say little known, for true that only a fraction of our organization’s membership like most composers of motion picture scores, Shield’s is able to attend our numerous rallies, no matter how wide name is not remembered, but his music is unforgettable! spread their locations may be. This is one reason why Leroy Shield’s compositions are as well known as those independent events where we may perform and opening of the music from “Gone with the Wind” and “The Wizard our collections to visitors are such important parts of our of Oz,” and like their scores composers, his name is vir- hobby. tually unknown (Figure 1). When an event from another organization that is near Leroy Shield wrote most of the endearing melodies and dear to one’s heart comes along, it is especially grati- which make up the musical background on the early fying to share our COAA interests as circumstances allow. 1930s comedies of Laurel and Hardy and the Our It is fun for everyone involved, and it may even lead to Gang/Little Rascals, along with other wonderful short new COAA memberships. -

“I Want Music Everywhere” Music, Operetta, and Cultural Hierarchy at the Hal Roach Studios

4 “I Want Music Everywhere” Music, Operetta, and Cultural Hierarchy at the Hal Roach Studios In their 1928 stockholders’ report, the Hal Roach Studios’ board of directors anticipated the company’s conversion to sound with calm assuredness: The last few months has [sic] witnessed the advent of another element in the produc- tion field; that is, the talking or sound pictures. It is, of course, difficult to foretell what the eventual outcome of talking pictures will be or the eventual form they will assume. One thing is certain, however, that is that they are at the present time an element in the amusement field apparently having a definite appeal to the public, and properly handled, it promises to be a great addition to the entertainment value of pictures and a great aid to the producer in building up the interest in the picture intended. The company has placed itself in a position to gain by any and all new methods and devices introduced in the field.1 Confidence is to be expected in a stockholders’ statement, but for the Roach Studios such an attitude likely came easy, at least in comparison with the com- petition. Unlike the independent producer-distributor Educational—which had initially flubbed its transition by backing the Vocafilm technology—the Roach Studios enjoyed the luxury of a financing and distribution deal with industry powerhouse Loew’s-MGM and opted to follow the parent company’s lead in entering the uncertain waters ahead. The Roach organization was, for example, included in Loew’s-MGM’s initial contract with Electrical Research Products, Inc. -

The Black.Ha Wk Films Collection

FILM PRESERVATION ASSOCIATES 8307 San Fernando Road Sun Valley, CA 91352 Telephone: 818 768-5376 Proudly Presenting in 16mm film ... THE BLACK.HAWK FILMS COLLECTION rrfie 'BfackJiawf(!Ji[ms Li6rary is 6aclcJ !for forty years1 '13facf(liawf('s vast fi6rary of 6eautijuffy reproaucea vintage movies set a worU-renoumea stanaanf for quafity. J-{ere is !fPJlls secona group of re[eases, joining tlie initia{fifty fi[ms refeasea in s eptem6er. 'We wi{[ announce aaaitiona{ se[ections on a regufar 6asis unti{ severa{ liunarea tit[es are again ·in print.· Jll{[ are new1 first-cfass prints, prompt[y aeCiverea. Prices shown are for films with rights for home and non-theatrical exhibition; please inquire if you desire theatrical, television or stock footage clearance. Hal Roach Productions (marked with an (*) asterisk) may be shipped only to destinations in the United States and Canada. Other terms of service follow the list of films. Winter 1990 Stan Laurel & Oliver Hardy THE CHIMP• (1932) $210 TI-IE CHIMP was the first of several L&H comedies with imaginatively animated opening title sequences. in this case two clowns holding a trampoline which rtps to reveal e<;1ch title. Previously unavailable. we're delighted to announce our prints have the ORIGINAL MAIN TITLES RESJPRED, Beyond the stunning titles, we find Stanley being paid off with a flea circus and Ollie with Ethel "the human chimpanzee" when the circus they work for goes broke. Ala "Angora Love," they have to hide their new assets from the landlord. Toe chimp takes over the best bed forcing the boys to sleep in the less good one commandeered by the fleas. -

Guide to the Groucho Marx Collection

Guide to the Groucho Marx Collection NMAH.AC.0269 Franklin A. Robinson, Jr. and Wendy Shay 2001 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 6 Series 1: Correspondence, 1932-1977, undated..................................................... 6 Series 2: Publications, Manuscripts, and Print Articles by Marx, 1930-1958, undated .................................................................................................................................. 8 Series 3: Scripts and Sketches, 1939-1959, undated............................................. -

Untitled Review, New Yorker, September 19, 1938, N.P., and “Block-Heads,” Variety, August, 31, 1938, N.P., Block-Heads Clippings File, BRTC

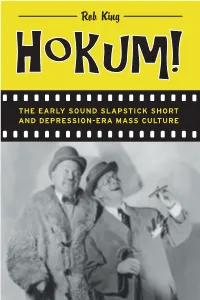

Luminos is the open access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserving and reinvigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org The publisher gratefully acknowledges the generous support of the Ahmanson Foundation Humanities Endowment Fund of the University of California Press Foundation. Hokum! Hokum! The Early Sound Slapstick Short and Depression-Era Mass Culture Rob King UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advanc- ing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Oakland, California © 2017 by Robert King This work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND license. To view a copy of the license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses. Suggested citation: King, Rob. Hokum! The Early Sound Slapstick Short and Depression-Era Mass Culture. Oakland: University of California Press, 2017. doi: https://doi.org/10.1525/luminos.28 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data King, Rob, 1975– author. Hokum! : the early sound slapstick short and Depression-era mass culture / Rob King. Oakland, California : University of California Press, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index. -

NOV 2 1 2014 of the City of Los Angeles

ACCELERATED REVIEW PROCESS - E Office of the City Engineer Los Angeles California To the Honorable Council NOV 2 1 2014 Of the City of Los Angeles Honorable Members: C. D. No. 13 SUBJECT: Hollywood Boulevard and Vine Street - Walk of Fame Additional Name in Terrazzo Sidewalk — PHARRELL WILLIAMS RECOMMENDATIONS: A. That the City Council designate the unnumbered location situated one sidewalk square southerly of and between numbered locations 74A and 74a as shown on Sheet #10 of Plan D-13788 for the Hollywood Walk of Fame for the installation of the name of Pharrell Williams at 6270 Hollywood Boulevard. B. Inform the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce of the Council's action on this matter. C. That this report be adopted prior to the date of the ceremony on December 4, 2014. FISCAL IMPACT STATEMENT: No General Fund Impact. All cost paid by permittee. TRANSMITTALS: 1. Unnumbered communication dated November 10, 2014, from the Hollywood Historic Trust of the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce, biographical information and excerpts from the minutes of the Chamber's meeting with recommendations. City Council 2 C. D. No. 13 DISCUSSION: The Walk of Fame Committee of the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce has submitted a request for insertion into the Hollywood Walk of Fame the name of Pharrell Williams. The ceremony is scheduled for Thursday, December 4, 2014 at 11:30 a.m. The communicant's request is in accordance with City Council action of October 18, 1978, under Council File No. 78-3949. Following the Council's action of approval, and upon proper application and payment of the required fee, an installation permit can be secured at 201 N. -

1 HIST/HRS 169 – Summary 2A Spring 2018 Hollywood And

HIST/HRS 169 – Summary 2A Spring 2018 Hollywood and Censorship 1920-30: The Ghost of Fatty Arbuckle Middle class reform movements were very powerful in the early 20th century. Progressives, middle classes, women and preachers pushed hard for Prohibition, women’s suffrage, and the censorship of the Hollywood product that some were convinced was undercutting the moral standards of America’s youth. Church groups were also very active, especially beginning in the 1920s. By about 1930 Catholic groups were the most powerful: they watched films carefully for potential insults to the Catholic Church and to immigrant Catholic groups and for dangers to the moral purity of Catholic youth. In the early 30s Catholic leaders organized ‘Legions of Decency’, whose job was to arrange boycotts of Hollywood movies that Catholic leaders considered objectionable. American public opinion around 1920 was fascinated with Hollywood society that had, according to Robert Sklar, entered the ‘Aquarian Age’ (free-thinking, self-indulgent, sybaritic). Ordinary people followed their favorite stars – their personae, lifestyles and values -- in fan magazines and in the writings of gossip columnists. Despite the efforts of the studios to keep their stars’ image wholesome and family compatible, public opinion’s Magazine Cover, 1920 image was that Hollywood represented physical beauty, sensual self indulgence through drinking, drugs, sex, swimming, driving fast sports cars, living in palatial mansions and going to wild weekend parties. Anxieties were heightened by the migration of large numbers of “movie struck girls” to Hollywood to make fame and fortune; many of them were of course exploited by the system (by “leering foreigners with big noses and small ratty eyes” [Who are they?]), and according to popular legend, destroyed in the process. -

Read Book # Thelma Todd Movie Poster Art Stills Book

ADAETOTDE6HH \ eBook # Thelma Todd Movie Poster Art Stills Book (Paperback) Th elma Todd Movie Poster A rt Stills Book (Paperback) Filesize: 1.03 MB Reviews Here is the greatest publication i have study till now. I was able to comprehended every thing using this written e pdf. I am pleased to explain how here is the greatest pdf i have study within my own lifestyle and might be he best pdf for ever. (Leopold Moore) DISCLAIMER | DMCA FTNFEVCF8JEY # Book < Thelma Todd Movie Poster Art Stills Book (Paperback) THELMA TODD MOVIE POSTER ART STILLS BOOK (PAPERBACK) To download Thelma Todd Movie Poster Art Stills Book (Paperback) eBook, remember to click the web link beneath and save the ebook or have accessibility to additional information which are highly relevant to THELMA TODD MOVIE POSTER ART STILLS BOOK (PAPERBACK) book. Createspace Independent Publishing Platform, United States, 2017. Paperback. Condition: New. Language: English . Brand New Book ***** Print on Demand *****.Thelma Todd was the perfect combination: a beautiful and funny actress, a great onscreen comedienne. Today s audiences may best remember her for her memorable supporting roles in films of Laurel and Hardy and the Marx Brothers. But Todd s film career was so much larger. In the 1930s, she starred in a successful short subject series with Zasu Pitts and later with Patsy Kelly for Hal Roach Studios. During the Depression, she was more popular than say Goldie Hawn or Farrah Fawcett. In all, she appeared in 115 films, with her first being --at 21 years of age-- as Lorraine Lane in Fascinating Youth (1926). -

IPG Spring 2020 Film Titles - January 2020 Page 1

Film Titles Spring 2020 {IPG} Stars and Wars (2nd Edition) The Film Memoirs and Photographs of Alan Tomkins Alan Tomkins, Oliver Stone A paperback edition of Oscar-nominated Alan Tomkins' film memoirs and photographs Summary The History Press In Stars and Wars , Oscar-nominated art director Alan Tomkins reveals his unpublished film artwork and 9780750992565 behind-the-scenes photographs from an acclaimed career that spanned over 40 years in both British and Pub Date: 5/1/20 Hollywood cinema. Tomkins’ art appeared in celebrated films such as Saving Private Ryan , JFK , Robin Hood On Sale Date: 5/1/20 $34.95 USD/£20.00 GBP Prince of Thieves , The Empire Strikes Back (which would earn him his Oscar nomination), Lawrence of Arabia , Discount Code: LON Casino Royale , Battle of Britain and Batman Begins , and he shares his own unique experiences alongside Trade Paperback these wonderful illustrations and photographs for the very first time. Having worked alongside eminent 168 Pages directors such as David Lean, Oliver Stone, Stanley Kubrick, Franco Zeffirelli and Clint Eastwood, Tomkins has Carton Qty: 1 now produced a book that is a must-have for all lovers of classic cinema. Performing Arts / Film & Video Contributor Bio PER004010 Alan Tomkins ' film career spanned more than 40 years, in which time he went from being a draughtsman on 8.9 in H | 9.8 in W Lawrence of Arabia to becoming an acclaimed and sought-after art director on films such as Saving Private Ryan , The Empire Strikes Back , JFK, Casino Royale , and Batman Begins . Oliver Stone worked with Tomkins on Natural Born Killers and JFK .