Viewer Who May Quote Passages in a Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Political Ideas and Movements That Created the Modern World

harri+b.cov 27/5/03 4:15 pm Page 1 UNDERSTANDINGPOLITICS Understanding RITTEN with the A2 component of the GCE WGovernment and Politics A level in mind, this book is a comprehensive introduction to the political ideas and movements that created the modern world. Underpinned by the work of major thinkers such as Hobbes, Locke, Marx, Mill, Weber and others, the first half of the book looks at core political concepts including the British and European political issues state and sovereignty, the nation, democracy, representation and legitimacy, freedom, equality and rights, obligation and citizenship. The role of ideology in modern politics and society is also discussed. The second half of the book addresses established ideologies such as Conservatism, Liberalism, Socialism, Marxism and Nationalism, before moving on to more recent movements such as Environmentalism and Ecologism, Fascism, and Feminism. The subject is covered in a clear, accessible style, including Understanding a number of student-friendly features, such as chapter summaries, key points to consider, definitions and tips for further sources of information. There is a definite need for a text of this kind. It will be invaluable for students of Government and Politics on introductory courses, whether they be A level candidates or undergraduates. political ideas KEVIN HARRISON IS A LECTURER IN POLITICS AND HISTORY AT MANCHESTER COLLEGE OF ARTS AND TECHNOLOGY. HE IS ALSO AN ASSOCIATE McNAUGHTON LECTURER IN SOCIAL SCIENCES WITH THE OPEN UNIVERSITY. HE HAS WRITTEN ARTICLES ON POLITICS AND HISTORY AND IS JOINT AUTHOR, WITH TONY BOYD, OF THE BRITISH CONSTITUTION: EVOLUTION OR REVOLUTION? and TONY BOYD WAS FORMERLY HEAD OF GENERAL STUDIES AT XAVERIAN VI FORM COLLEGE, MANCHESTER, WHERE HE TAUGHT POLITICS AND HISTORY. -

New Labour, Old Morality

New Labour, Old Morality. In The IdeasThat Shaped Post-War Britain (1996), David Marquand suggests that a useful way of mapping the „ebbs and flows in the struggle for moral and intellectual hegemony in post-war Britain‟ is to see them as a dialectic not between Left and Right, nor between individualism and collectivism, but between hedonism and moralism which cuts across party boundaries. As Jeffrey Weeks puts it in his contribution to Blairism and the War of Persuasion (2004): „Whatever its progressive pretensions, the Labour Party has rarely been in the vanguard of sexual reform throughout its hundred-year history. Since its formation at the beginning of the twentieth century the Labour Party has always been an uneasy amalgam of the progressive intelligentsia and a largely morally conservative working class, especially as represented through the trade union movement‟ (68-9). In The Future of Socialism (1956) Anthony Crosland wrote that: 'in the blood of the socialist there should always run a trace of the anarchist and the libertarian, and not to much of the prig or the prude‟. And in 1959 Roy Jenkins, in his book The Labour Case, argued that 'there is a need for the state to do less to restrict personal freedom'. And indeed when Jenkins became Home Secretary in 1965 he put in a train a series of reforms which damned him in they eyes of Labour and Tory traditionalists as one of the chief architects of the 'permissive society': the partial decriminalisation of homosexuality, reform of the abortion and obscenity laws, the abolition of theatre censorship, making it slightly easier to get divorced. -

S P R I N G 2 0 0 3 Upfront 7 News Politics and Policy Culture And

spring 2003 upfront culture and economy environment 2 whitehall versus wales communications 40 rural survival strategy 62 making development analysing the way Westminster 33 gareth wyn jones and einir sustainable shares legislative power with ticking the box young say we should embrace kevin bishop and unpacking the Welsh 2001 Cardiff Bay robert hazell ‘Development Domains’ as a john farrar report on a census results denis balsom says Wales risks getting the central focus for economic new study to measure our finds subtle connections worst of both worlds policy in the Welsh countryside impact on the Welsh between the language and cover story cover environment 7 news nationality 43 making us better off steve hill calls for the 64 mainstreaming theatre special Assembly Government to renewable energy politics and policy adopt a culture of evaluation peter jones says Wales 13 35 i) a stage for wales in its efforts to improve should move towards clear red water michael bogdanov says Welsh prosperity more sustainable ways of rhodri morgan describes the Cardiff and Swansea living distinctive policy approach should collaborate to developed by Cardiff Bay over science special produce the forerunner europe the past three years for a federal national 47 i) why we need a 15 red green theatre science strategy 66 team wales abroad eluned haf reports on the progressive politics 38 ii) modest venue – phil cooke charts Wales’ adam price speculates on melodramatic progress in venturing into new Welsh representation whether a coalition between debate the -

Introduction to Staff Register

REGISTER OF INTERESTS OF MEMBERS’ SECRETARIES AND RESEARCH ASSISTANTS (As at 15 October 2020) INTRODUCTION Purpose and Form of the Register In accordance with Resolutions made by the House of Commons on 17 December 1985 and 28 June 1993, holders of photo-identity passes as Members’ secretaries or research assistants are in essence required to register: ‘Any occupation or employment for which you receive over £410 from the same source in the course of a calendar year, if that occupation or employment is in any way advantaged by the privileged access to Parliament afforded by your pass. Any gift (eg jewellery) or benefit (eg hospitality, services) that you receive, if the gift or benefit in any way relates to or arises from your work in Parliament and its value exceeds £410 in the course of a calendar year.’ In Section 1 of the Register entries are listed alphabetically according to the staff member’s surname. Section 2 contains exactly the same information but entries are instead listed according to the sponsoring Member’s name. Administration and Inspection of the Register The Register is compiled and maintained by the Office of the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards. Anyone whose details are entered on the Register is required to notify that office of any change in their registrable interests within 28 days of such a change arising. An updated edition of the Register is published approximately every 6 weeks when the House is sitting. Changes to the rules governing the Register are determined by the Committee on Standards in the House of Commons, although where such changes are substantial they are put by the Committee to the House for approval before being implemented. -

POLITICAL ECONOMY for SOCIALISM Also by Makoto Itoh

POLITICAL ECONOMY FOR SOCIALISM Also by Makoto Itoh TilE BASIC TIIEORY OF CAPITALISM TilE VALUE CONTROVERSY (co-author with I. Steedman and others) TilE WORLD ECONOMIC CRISIS AND JAPANESE CAPITALISM VALUE AND CRISIS Political Economy for Socialism Makoto ltoh Professor of Economics University of Tokyo M St. Martin's Press © Makoto ltoh 1995 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London WIP 9HE. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. First published in Great Britain 1995 by MACMILLAN PRESS LTD Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 2XS and London Companies and representatives throughout the world A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-0-333-55338-1 ISBN 978-1-349-24018-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-24018-0 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 I 04 03 02 01 00 99 98 97 96 95 First published in the United States of America 1995 by Scholarly and Reference Division, ST. MARTIN'S PRESS, INC., 175 Fifth A venue, New York, N.Y. 10010 ISBN 978-0-312-12564-6 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data ltoh, Makoto, 1936-- Political economy for socialism I Makoto Itoh. -

Harriet Harman - MP for Camberwell and Peckham Monthly Report— November/December 2016

Camberwell and Peckham Labour Party Harriet Harman - MP for Camberwell and Peckham Monthly Report— November/December 2016 Camberwell & Peckham EC The officers of the Camberwell and Peckham Labour Party Ellie Cumbo Chair were elected at our AGM in November and I'd like to thank Caroline Horgan Vice-Chair Fundraising MichaelSitu Vice-Chair Membership them for taking up their roles and for all the work they will be Laura Alozie Treasurer doing. In 2017, unlike last year, there will be no elections so Katharine Morshead Secretary it’s an opportunity to build our relationship with local people, Lorin Bell-Cross Campaign Organiser support our Labour Council and discuss the way forward for Malc McDonald IT & Training Officer Richard Leeming IT & Training Officer the party in difficult times. I look forward to working with our Catherine Rose Women's Officer officers and all members on this. Youcef Hassaine Equalities Officer Jack Taylor Political Education Officer Happy New Year! Victoria Olisa Affiliates and Supporters Liaison Harjeet Sahota Youth Officer Fiona Colley Auditor Sunny Lambe Auditor Labour’s National NHS Campaign Day Now we’ve got a Tory government again, and as always happens with a Tory government, healthcare for local people suffers, waiting lists grow, it gets more difficult to see your GP, hospital services are stretched and health service staff are under more pressure. As usual there were further cuts to the NHS in Philip Hammond’s Autumn Statement last month. The Chancellor didn’t even mention social care in his speech. Alongside local Labour councillors Jamille Mohammed, Nick Dolezal & Jasmine Ali I joined local party members in Rye Lane to show our support for the #CareForTheNHS campaign. -

British Politics and Policy at LSE: Under New Leadership: Keir Starmer’S Party Conference Speech and the Embrace of Personality Politics Page 1 of 2

British Politics and Policy at LSE: Under new leadership: Keir Starmer’s party conference speech and the embrace of personality politics Page 1 of 2 Under new leadership: Keir Starmer’s party conference speech and the embrace of personality politics Eunice Goes analyses Keir Starmer’s first conference speech as Labour leader. She argues that the keynote address clarified the distinctiveness of his leadership style, and presented Starmer as a serious Prime Minister-in-waiting. Keir Starmer used his virtual speech to the 2020 party conference to tell voters that Labour is now ‘under a new leadership’ that is ‘serious about winning’ the next election. He also made clear that he is ready to do what it takes to take Labour ‘out of the shadows’, even if that involves embracing personality politics and placing patriotism at the centre of the party’s message. Starmer has been Labour leader for only five months but he has already established a reputation as a credible and competent leader of the opposition. Opinion polls routinely put him ahead of the Prime Minister Boris Johnson in the credibility stakes, and the media has often praised his competence and famous forensic approach to opposition politics. This is a welcome new territory for Labour – Starmer’s predecessors, Jeremy Corbyn and Ed Miliband, struggled to endear themselves to the average voter – so it is no surprise that he is making the most of it. In fact, judging by some killer lines used in this speech, the Labour leader is enjoying his new role as the most popular politician in British politics. -

Unique Paths to Devolution Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland

Unique Paths to Devolution Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland Arthur Aughey, Eberhard Bort, John Osmond The Institute of Welsh Affairs exists to promote quality research and informed debate affecting the cultural, social, political and economic well-being of Wales. The IWA is an independent organisation owing no allegiance to any political or economic interest group. Our only interest is in seeing Wales flourish as a country in which to work and live. We are funded by a range of organisations and individuals, including the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust, the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation, the Waterloo Foundation and PricewaterhouseCoopers. For more information about the Institute, its publications, and how to join, either as an individual or corporate supporter, contact: IWA - Institute of Welsh Affairs 4 Cathedral Road Cardiff CF11 9LJ Tel 029 2066 0820 Fax 029 2023 3741 Email [email protected] Web www.iwa.org.uk www.clickonwales.org £7.50 ISBN 978 1 904773 56 6 February 2011 The authors Arthur Aughey is Professor of Politics at the University of Ulster and a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts. He is a Senior Fellow of the Centre for British Politics at the University of Hull and Fellow of the Institute for British Irish Studies at University College Dublin. His recent publications include Nationalism Devolution and the Challenge to the United Kingdom State (London: Pluto Press 2001); Northern Ireland Politics: After the Belfast Agreement (London: Routledge 2005); and The Politics of Englishness (Manchester: Manchester University Press 2007). He is currently a Leverhulme Major Research Fellow and gratefully acknowledges its financial assistance in the writing of this essay. -

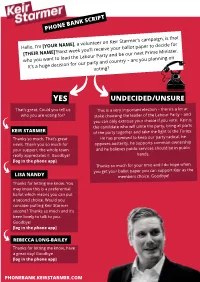

Script Flow Chart

PHONE BANK SCRIPT at ’s campaign, is th r on Keir Starmer AME], a voluntee de for ello, I’m [YOUR N llot paper to deci H ’ll receive your ba E]?Next week you e Minister. [THEIR NAM d be our next Prim e Labour Party an u want to lead th u planning on who yo d country – are yo n for our party an It’s a huge decisio voting? YES UNDECIDED/UNSURE That’s great. Could you tell us This is a very important election – there’s a lot at who you are voting for? stake choosing the leader of the Labour Party – and you can only exercise your choice if you vote. Keir is the candidate who will unite the party, bring all parts KEIR STARMER of the party together and take the fight to the Tories. cal, he Thanks so much. That’s great He has promised to keep our party radi wnership news. Thank you so much for opposes austerity, he supports common o in public your support, the whole team and he believes public services should be really appreciates it. Goodbye! hands. [log in the phone app] Thanks so much for your time and I do hope when you get your ballot paper you can support Keir as the LISA NANDY members choice. Goodbye! Thanks for letting me know. You may know this is a preferential ballot which means you can put a second choice. Would you consider putting Keir Starmer second? Thanks so much and it’s been lovely to talk to you. -

Antisemitism and the 'Alternative Media'

King’s Research Portal Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Allington, D., & Joshi, T. (2021). Antisemitism and the 'alternative media'. Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 11. Aug. 2021 Copyright © 2021 Daniel Allington Antisemitism and the ‘alternative media’ Daniel Allington with Tanvi Joshi January 2021 King’s College London About the researchers Daniel Allington is Senior Lecturer in Social and Cultural Artificial Intelligence at King’s College London, and Deputy Editor of Journal of Contemporary Antisemitism. -

Beyond Factionalism to Unity: Labour Under Starmer

Beyond factionalism to unity: Labour under Starmer Article (Accepted Version) Martell, Luke (2020) Beyond factionalism to unity: Labour under Starmer. Renewal: A journal of social democracy, 28 (4). pp. 67-75. ISSN 0968-252X This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/95933/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk Beyond Factionalism to Unity: Labour under Starmer Luke Martell Accepted version. Final article published in Renewal 28, 4, 2020. The Labour leader has so far pursued a deliberately ambiguous approach to both party management and policy formation. -

Resolving Polanyi's Paradox

11 afterword: resolving polanyi’s paradox Michael Burawoy Over the last 30 years Karl Polanyi’s The Great Transformation, first published in 1944, has become a canonical text in several inter-related social sciences – sociology, geography, anthropology, international political economy, as well as making in-roads into political science and economics. Undoubtedly, part of its appeal lies in the resonance of his theories with our times which have been marked by the deregulation of markets and their extension into new realms. Polanyi argued that the rise of market fundamentalism had devastating conse- quences for society, leading to protective countermovements that could be of a progressive or reactionary character. From the perspective of today’s market fun- damentalism, Polanyi’s countermovement effectively frames, on the one hand, the democratic social movements of 2011, including the Arab Spring, Occupy, and Indignados, and, on the other hand, the more recent advance of illiberal democracies, often veering toward dictatorships, in Turkey, Poland, Hungary, the Philippines, Brazil, Italy, Israel and Egypt. It also frames an understanding of such popular movements behind Brexit, Trumpism, the Five Star Movement, and the Yellow Vests as a reaction to an expanding market that commodifies, denigrates and excludes. It is the obvious appeal of Polanyi’s argument that now leads commentators to evaluate his writings critically and with renewed inten- sity, searching for answers to crises of a global scale. critiques of polanyi The most common criticism of The Great Transformation is Polanyi’s failure to anticipate another round of market fundamentalism beginning in the 1970s that has continued virtually unabated for nearly 50 years.