Features of Settlement in Australia by Macedonians from the Aegean Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 THESSOLONIANS 1:1-10 the Gospel Received in Much Assurance and Much Affliction the Vitality of a Living Christian Faith

1 THESSOLONIANS 1:1-10 The Gospel Received in Much Assurance and Much Affliction The Vitality of a Living Christian Faith Thessalonica was a Roman colony located in Macedonia and not in Greece proper. The city was first named Therma because of the hot springs in that area. In 316 A.D. Cassander, one of the four generals who divided up the empire of Alexander the Great took Macedonia and made Thessalonica his home base. He renamed the city in memory of his wife, Thessalonike, who was a half sister of Alexander. The city is still in existence and is now known as Salonika. Rome had a somewhat different policy with their captured people from what many other nations have had. For example, it seems that we try to Americanize all the people throughout the world, as if that would be the ideal. Rome was much wiser than that. She did not attempt to directly change the culture, the habits, the customs, or the language of the people whom she conquered. Instead, she would set up colonies which were arranged geographically in strategic spots throughout the empire. A city which was a Roman colony would gradually adopt Roman laws and customs and ways. In the local department stores you would see the latest things they were wearing in Rome itself. Thus these colonies were very much like a little Rome. Thessalonica was such a Roman colony, and it was an important city in the life of the Roman Empire. It was Cicero who said, “Thessalonica is in the bosom of the empire.” It was right in the center or the heart of the empire and was the chief city of Macedonia. -

GO BEYOND the DESTINATION on Our Adventure Trips, Our Guides Ensure You Make the Most of Each Destination

ADVENTURES GO BEYOND THE DESTINATION On our adventure trips, our guides ensure you make the most of each destination. You’ll find hidden bars, explore cobbled lanes, and eat the most delectable meals. Join an adventure, tick off the famous wonders and discover Europe’s best-kept secrets! Discover more Travel Styles and learn about creating your own adventure with the new 2018 Europe brochure. Order one today at busabout.com @RACHAEL22_ ULTIMATE BALKAN ADVENTURE SPLIT - SPLIT 15 DAYS CROATIA Mostar SARAJEVO SERBIA ROMANIA SPLIT BELGRADE (START) BOSNIA Dubrovnik MONTENEGRO Nis BULGARIA KOTOR SKOPJE Budva MACEDONIA OHRID ITALY TIRANA ALBANIA Gjirokaster THESSALONIKI GREECE METEORA Delphi Thermopylae Overnight Stays ATHENS NEED TO KNOW INCLUSIONS • Your fantastic Busabout crew • 14 nights’ accommodation • 14 breakfasts • All coach transport @MISSLEA.LEA • Transfer to Budva • Orientation walks of Thessaloniki, Tirana, Gjirokaster, Nis and Split • Entry into two monasteries in Meteora The Balkans is the wildest part of Europe to travel in. You’ll be enthralled by the cobbled • Local guide in Mostar castle lanes, satiated by strange exotic cuisine, and pushed to your party limits in its • Local guide in Delphi, plus site and offbeat capitals. Go beyond the must-sees and venture off the beaten track! museum entrance FREE TIME Chill out or join an optional activity • 'Game of Thrones' walking tour in Dubrovnik DAY 5 | KALAMBAKA (METEORA) - THERMOPYLAE - ATHENS • Sunset at the fortress in Kotor HIGHLIGHTS We will visit two of the unique monasteries perched • Traditional Montenegrin restaurant dinner • Scale the Old Town walls of Dubrovnik high on top of incredible rocky formations of Meteora! • Bar hopping in Kotor • Breathtaking views of Meteora monasteries After taking in the extraordinary sights we visit the • Traditional Greek cuisine dinner • Be immersed in the unique culture of Sarajevo Spartan Monument in Thermopylae on our way to • Walking tour in Athens • Plus all bolded highlights in the itinerary Athens. -

LESSON TITLE: the Call to Macedonia THEME: We Must Be

Devotion NT301 CHILDREN’S DEVOTIONS FOR THE WEEK OF: ____________________ LESSON TITLE: The Call to Macedonia THEME: We must be obedient to the voice of the Lord! SCRIPTURE: Acts 16:6-10 Dear Parents… Welcome to Bible Time for Kids! Bible Time for Kids is a series of daily devotions for children and their families. Our purpose is to supplement our Sunday morning curriculum and give you an opportunity to encourage your children to develop a daily devotional life. We hope you and your family will be blessed as you study God’s Word together. This week in Children’s Church we learned about The Call to Macedonia. The theme was “We must be obedient to the voice of the Lord.” Paul saw a vision of a man from Macedonia. He thought that he was going to go to Asia or Bythinia to share the gospel, but God had other plans. When God showed Paul what He wanted him to do, he immediately obeyed. God still speaks to us today through His Word and through His Holy Spirit. Whenever we hear the voice of the Lord we also need to be obedient. We will look at how we can listen to God and what our response should be this week in our devotion time. The section of scripture that we studied was Acts 16:6-10. The following five devotions are based on either the scripture and/or the theme for Sunday’s lesson. As a starting point it would be good for you to review these verses with your children. -

Blood Ties: Religion, Violence, and the Politics of Nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878

BLOOD TIES BLOOD TIES Religion, Violence, and the Politics of Nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878–1908 I˙pek Yosmaog˘lu Cornell University Press Ithaca & London Copyright © 2014 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. First published 2014 by Cornell University Press First printing, Cornell Paperbacks, 2014 Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Yosmaog˘lu, I˙pek, author. Blood ties : religion, violence,. and the politics of nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878–1908 / Ipek K. Yosmaog˘lu. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8014-5226-0 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8014-7924-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Macedonia—History—1878–1912. 2. Nationalism—Macedonia—History. 3. Macedonian question. 4. Macedonia—Ethnic relations. 5. Ethnic conflict— Macedonia—History. 6. Political violence—Macedonia—History. I. Title. DR2215.Y67 2013 949.76′01—dc23 2013021661 Cornell University Press strives to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the fullest extent possible in the publishing of its books. Such materials include vegetable-based, low-VOC inks and acid-free papers that are recycled, totally chlorine-free, or partly composed of nonwood fibers. For further information, visit our website at www.cornellpress.cornell.edu. Cloth printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Paperback printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To Josh Contents Acknowledgments ix Note on Transliteration xiii Introduction 1 1. -

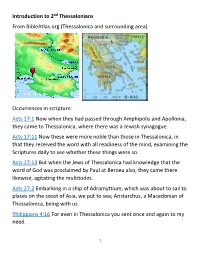

2 Thessalonians Introductory Handout

Introduction to 2nd Thessalonians From BibleAtlas.org (Thessalonica and surrounding area) Occurrences in scripture: Acts 17:1 Now when they had passed through Amphipolis and Apollonia, they came to Thessalonica, where there was a Jewish synagogue. Acts 17:11 Now these were more noble than those in Thessalonica, in that they received the word with all readiness of the mind, examining the Scriptures daily to see whether these things were so. Acts 17:13 But when the Jews of Thessalonica had knowledge that the word of God was proclaimed by Paul at Beroea also, they came there likewise, agitating the multitudes. Acts 27:2 Embarking in a ship of Adramyttium, which was about to sail to places on the coast of Asia, we put to sea; Aristarchus, a Macedonian of Thessalonica, being with us. Philippians 4:16 For even in Thessalonica you sent once and again to my need. 1 2 Timothy 4:10 for Demas left me, having loved this present world, and went to Thessalonica; Crescens to Galatia, and Titus to Dalmatia. From the International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: THESSALONICA thes-a-lo-ni'-ka (Thessalonike, ethnic Thessalonikeus): 1. Position and Name: One of the chief towns of Macedonia from Hellenistic times down to the present day. It lies in 40 degrees 40 minutes North latitude, and 22 degrees 50 minutes East longitude, at the northernmost point of the Thermaic Gulf (Gulf of Salonica), a short distance to the East of the mouth of the Axius (Vardar). It is usually maintained that the earlier name of Thessalonica was Therma or Therme, a town mentioned both by Herodotus (vii.121;, 179;) and by Thucydides (i0.61; ii.29), but that its chief importance dates from about 315 B.C., when the Macedonian king Cassander, son of Antipater, enlarged and strengthened it by concentrating there the population of a number of neighboring towns and villages, and renamed it after his wife Thessalonica, daughter of Philip II and step-sister of Alexander the Great. -

Titus - Building the Church

Bible Study: Titus - Building the Church Author: Paul, an apostle of Jesus Christ Audience: Titus, a minister at Crete Date: approximately 63 A.D. Location: unknown (possibly Nicopolis) Theme: Organizing and supervising the church Genre: epistle/prose Outline Salutation (1:1-4) Qualifications of Elders (1:5-9) Dealing with False Teachers (1:10-16) Observation 1:1 Paul considered himself God’s slave; his task was to spread Christian faith and truth 1:2 Unlike Cretans, God cannot lie; He promised eternal life before ages of time, but… 1:3: In due time (i.e., a delay), He revealed His word and commanded Paul to proclaim it 1:4 Addressed to Titus, a fellow believer; a salutation of grace and peace 1:5 Paul left Titus in Create to appoint elders (plural) in every city (singular) 1:6 The qualifications for an elder; the husband (male) of one wife (female) 1:7 An elder is an overseer (interchangeable terms), God’s steward (manager); not greedy 1:8 Hospitable contrasts greedy; prudent implies wisdom; upright implies righteous 1:9 An elder must be doctrinally orthodox, so he can teach the truth and refute error 1:10 Because there are MANY rebels, bigmouths & deceivers (especially among the Jews) 1:11 They are teaching error for money; Paul commands Titus to silence them 1:12 Ironically, a Cretan “prophet” said that Cretans are always liars, evil and lazy 1:13 Paul agreed (!), commanded Titus to reprove them severely (truth supersedes love) 1:14 Two problem areas: Jewish myths, commandments of heretical men 1:15 Unbelievers have a defiled mind (reason) and conscience (moral compass) 1:16 They claim to know God (Jews?) but deny Him by their sinful, corrupt deeds Interpretation In what sense was an elder to be “the husband of one wife” (1:6)? The precise implications of "the husband of but one wife" have been debated through the centuries. -

Walking in Greece | Small Group Tour for Seniors

Australia 1300 888 225 New Zealand 0800 440 055 [email protected] From $9,650 AUD Single Room $11,250 AUD Twin Room $9,650 AUD Prices valid until 30th December 2021 18 days Duration Greece Destination Level 3 - Moderate to Challenging Activity Walking in Greece Nov 08 2021 to Nov 25 2021 Walking in Greece Join Odyssey Traveller as we go walking in Greece, venturing beyond the famous tourist destination of Athens and the Greek islands’ well- trodden paths—and into the small villages and breathtaking sites of northern mainland Greece. Our guided walking tour will take us to towns carrying the names, ancient sites, and cultural marks of the Hellenic Republic’s long history and incredible mythology—Western Macedonia, Ioannina, Epirus, Meteora, and even the slopes of Mount Olympus. After city tours in Athens and Thessaloniki, we will begin our walking tour in earnest in the mountainous municipality of Grevena in Western Walking in Greece 28-Sep-2021 1/18 https://www.odysseytraveller.com.au Australia 1300 888 225 New Zealand 0800 440 055 [email protected] Macedonia, a truly small town (fewer than 200 residents). We will walk through lush forests and up mountain slopes, along lakefronts and beach shores, heading to small waterfalls and clear springs, and up viewpoints to see incredible geological formations such as the Vikos Gorge and the clifftop monasteries of Meteora, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. We will enjoy meals at local tavernas and try sumptuous dishes featuring local specialties. We will also have days where we will have picnic lunches, sitting in the midst of beautiful sceneries, and free time to explore the villages on our own. -

Resurrection As Anti-Imperial Gospel Founded by Cassander, Son of Antipater, Who Had Been Delegated Responsibility for Macedonia by Alexander the Great

Introduction In 1 Thess. 1:9b-10 (“you turned to God from idols, to serve a living and true God, and to wait for his Son from heaven, whom he raised from the dead—Jesus, who rescues us from the wrath that is coming”1), Paul makes three main statements. The first concerns the actions of the Thessalonians, the second regards the action of God, and the third involves the activity of Jesus. In the first statement—concerning the Thessalonians’ actions—there are three subsidiary statements. First, the Thessalonians have turned to God from idols. Second, they have turned in order to serve the living and true God. And third, they are waiting for the Son from the heavens. The second of Paul’s main statements involves the activity of God—that he has raised his son from the dead. This is the crucial statement of the three, for from it all the other actions follow—it is what we would call the precipitatory action. What seems to be clear is that the actions of the Thessalonians are all part of their response to the news that Jesus has been raised from the dead. The third main statement concerns the actions of Jesus, which I suggest is Paul’s affirmation and encouragement to the Thessalonians that since they have made their response to the news concerning God’s actions, Jesus himself is now acting in their favor—“who rescues us from the wrath that is coming.” The second of Paul’s main statements I have outlined here is the critical one in this study. -

Macedonia: a Secular Conflict Area

Document Analysis 47/2015 September 30, 2015 Pedro Sánchez Herráez Macedonia: a secular conflict area Visit the WEBSITE Receive Electronic Newsletter This document has been translated by a Translation and Interpreting Degree student doing work experience, ENRIQUE GARCÍA, under the auspices of the Collaboration Agreement between the Universidad Pontificia Comillas, Madrid, and the Spanish Institute of Strategic Studies. Macedonia: a secular conflict area Abstract: Macedonia, a small country located in the heart of the Balkans, has a capital importance in allowing the flow of people and resources to and from Europe, given the difficult terrain in the area. This old reality has had great influence in the development of a rich and complex history that is marked by wars over the control of the territory –for the larger area known as Macedonia region in which this nation is included-. They are so intense that in the nineteenth century the term “Macedonian question” was created as a way to define an array of almost-permanent disputes. A brief review of the dynamics of this land, culminating in the birth of today´s Macedonia, and formulating a question in the framework of the final conclusions, structure the present analysis. Keywords: Macedonia, internal disputes, external disputes, communication routes, key terrain, Powers, Empires, “Macedonian question”, Balkans. Analytical Document 47/2015 1 MACEDONIA: A SECULAR CONFLICT AREA Pedro Sánchez Herráez Introduction Even though Macedonia avoided the war clouds that hit the territory of the former Yugoslavia during the 1990s and led to both the extinction of the so-called “Yugoslav experiment”, which was fortunate for some and a failure for others,1 and to the creation of independent states that were former federated republics; it cannot be concluded that its territory has not been subjected to numerous tensions and conflicts, for both endogenous and exogenous issues. -

Chapter 3 GREEK HISTORY

Chapter 3 GREEK HISTORY The French Academician Michel Déon has written: "In Greece contemporary man, so often disoriented, discovers a quite incredible joy; he discovers his roots.” GREECE - HELLAS [Greeks] denoted the inhabitants of 700 or more city-states in the Greek peninsula The roots of much of the Western world lie in including Epirus, Macedonia, Thrace, Asia the civilizations of the ancient Greece and Minor, and many of the shores of the Rome. This chapter is intended to bring you Mediterranean and the Black Seas. small pieces of those rich roots of our Greek past. The objectives of this chapter are: first, Life in Greece first appeared on the Halkidiki to enrich our consciousness with those bits of Peninsula dated to the Middle Paleolithic era information and to build an awareness of what (50.000 B.C). Highly developed civilizations it means to be connected with the Greek past; appeared from about 3000 to 2000 B.C. and second, to relate those parts of Greek During the Neolithic period, important history that affected the migrations of the cultural centers developed, especially in Greeks during the last few centuries. Thessaly, Crete, Attica, Central Greece and Knowledge of migration patterns may prove the Peloponnesus. to be very valuable in your search for your ancestors. The famous Minoan advanced prehistoric culture of 2800-1100 B.C. appeared in Crete. We see more artistic development in the Bronze Age (2000 BC), during which Crete was the center of a splendid civilization. It was a mighty naval power, wealthy and powerful. Ruins of great palaces with beautiful paintings were found in Knossos, Phaistos, and Mallia. -

The Saracen Defenders of Constantinople in 378 Woods, David Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Fall 1996; 37, 3; Proquest Pg

The Saracen defenders of Constantinople in 378 Woods, David Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Fall 1996; 37, 3; ProQuest pg. 259 The Saracen Defenders of Constantinople in 378 David Woods RITING ca 391, the historian Ammianus Marcellinus has left us a vivid description of the Roman defense of W Constantinople against the Goths shortly after their crushing defeat by these Goths at Adrianopolis on 9 August 378 (31. 16.4ff): Unde Constantinopolim, copiarum cumulis inhiantes amplis simis, formas quadratorum agmimum insidiarum metu ser vantes, ire ocius festinabant, multa in exitium urbis inclitae molituri. Quos inferentes sese immodice, obicesque portarum paene pulsantes, hoc casu caeleste reppulit numen. Saracen orum cuneus (super quorum origine moribusque diversis in locis rettulimus plura), ad furta magis expeditionalium re rum, quam ad concursatorias habilis pugnas, recens illuc accersitus, congressurus barbarorum globo repente con specto, a civitate fidenter e rup it, diuque extento certamine pertinaci, aequis partes discessere momentis. Sed orientalis turma novo neque ante viso superavit eventu. Ex ea enim crinitus quidam, nudus omnia praeter pubem, subraucum et lugubre strepens, educto pugione, agmini se medio Goth orum inseruit, et interfecti hostis iugulo labra admovit, effusumque cruorem exsuxit. Quo monstroso miraculo bar bari territi, postea non ferocientes ex more, cum agendum appeterent aliquid, sed ambiguis gressibus incedebant. 1 1 "From there [Perinthus] they [the Goths] hastened in rapid march to Con stantinople, greedy for its vast heaps of treasure, marching in square forma tions for fear of ambuscades, and intending to make mighty efforts to destroy the famous city. But while they were madly rushing on and almost knocking at the barriers of the gates, the celestial power checked them by the following event. -

Sparkling Wine Greek Ros É

WINE PYLOS rustic greek home cooking 212-473-0220 www.pylosrestaurant.com January 2019 white varietals assyrtiko 101. sigalas santorini oia santorini 2016 68 dessert wine 102. areti biblia chora kavala macedonia 2016 70 103. koutsoyannopoulos « nikteri » 1201. muscat of patras santorini 2015 76 (muscat) patras 42 | 13 glass 104. santo santorini 2016 45 | 13 glass 1202. oinomeio (muscat) peloponnese 42 | 13 glass moschofilero 1203. wishes eratines (375 ml) (malagouzia) 201. nasiakos mantinia 46 kolindros pieria 2013 70 arcadia peloponnese 2015 202. fteri troupis 40 | 11 glass arcadia peloponnese 2016 203. tselepos mantinia peloponnese 2016 50 retsina 301. omikron 38 | 11 glass other noble greek varietals and blends 402. gerovassiliou malagouzia (malagouzia) epanomi peloponnese 2016 66 403. oenogenesis en oeno… (sauv. blanc/ assyrtiko) drama macedonia 2016 52 | 14 glass 404. eratini wishes (assyrtiko/ malagouzia/ chard) Kolindros pieria 2016 52 | 14 glass 405. ovilios biblia chora (assyrtiko/ semillion) kavala macedonia 2016 80 sparkling wine greek ros é 501. zoe skouras (saint george/ moschofilero) agros peloponnese 2016 42 greek 502. oenogenesis en oeno… (grenache/ rouge/ cabernet) 1001. blink drama macedonia 2016 52 | 14 glass (muscat) lemnos north agean 46 | 18 split 503. parparoussis “petite fleur” 1002. tselepos amalia brut (sideritis) (moschofilero) peloponnese 2016 53 peloponnese 78 red varietals other noble greek varietals and blends 801. domaine oikonomou (liatiko) crete 2006 110 agiorgitiko 803. gerovasiliou « avaton » 601. mitravelas estate (limnio/ mavrotragano/ mavroudi) nemea peloponnese 2016 57 macedonia 2013 120 602. old monolith 804. moraitis reserve nemea peloponnese 2014 50 | 13 glass (mandilari/ monemvasia) naoussa paros 2015 40 | 12 glass 603. nasiakos nemea nemea peloponnese 2011 47 international varietals and blends 604.